Syphilis rates have been on the rise in recent years. In Spain, this sexually transmitted infection mainly affects men who have sex with men (MSM), many of whom are coinfected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).1 The natural history of both syphilis and HIV infection is affected by the coexistence of these diseases. The clinical manifestations of syphilis can progress more rapidly in patients with concomitant HIV infection, and aggressive and atypical forms of syphilis are also more common in this population.2

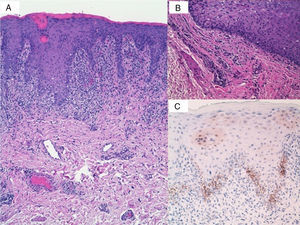

We report the case of 2 MSM with HIV infection who visited their dermatologist with genital lesions. The first man, aged 35 years, reported slightly pruritic lesions on the genitals that had appeared a month and a half earlier. He had applied topical corticosteroids, but there had been no improvement. Good immunologic control of his HIV infection had been maintained since 2009 without antiretroviral therapy. The physical examination revealed erythematous plaques with a lichenoid appearance and a tendency to coalesce on the dorsal aspect of the penis (Fig. 1 A and B). Blood test results brought by the patient, which included biochemistry, a complete blood count, and coagulation studies, were unremarkable. Skin biopsy revealed lichenoid dermatitis with effacement of the basal layer, exocytosis of neutrophils, and a band-like lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate (Fig. 2A). Numerous plasma cells were also observed on the wall and around the vessels of the dermis (Fig. 2B). Immunohistochemical staining for Treponema pallidum was positive (Fig. 2C). Syphilis serology was requested; the nontreponemal rapid plasma reagin (RPR) test showed antibody titers of 1/128 and the treponemal antibody test was positive.

A, Histologic findings: lichenoid dermatitis with effacement of the basal layer, exocytosis of neutrophils, and a band-like lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate together with numerous plasma cells on the wall and around the vessels of the dermis (hematoxylin-eosin, original magnification ×10). B, Histologic findings: detailed view of perivascular plasma cells (hematoxylin-eosin, original magnification ×40). C, Positive immunohistochemical staining for Treponema pallidum.

The second man, aged 29 years, had been diagnosed with HIV infection in 2011 and had achieved good immunologic control without pharmacologic treatment. He presented with mildly pruritic scrotal lesions of 1 month's duration. The lesions had been diagnosed as eczema and treated with topical corticosteroids, but there had been no improvement. The physical examination showed numerous pink plaques with a lichenoid appearance on the scrotum and at the base of the penis (Fig. 3). Laboratory tests, including biochemistry, a complete blood count, and coagulation studies, showed no alterations, and serology for syphilis was also negative. Histologic examination of a skin biopsy sample showed lichenoid dermatitis and immunohistochemical staining was positive for T pallidum. The RPR test was positive (titer, 1/64), as were the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and hemagglutination results.

Both patients were diagnosed with secondary syphilis mimicking lichen planus, with exclusive genital involvement. The clinical outcome was satisfactory in both cases, with complete resolution of lesions following treatment with intramuscular benzathine penicillin G 2.4 million units and a decline in RPR titers.

Cutaneous manifestations of secondary syphilis appear 3 to 12 weeks after the onset of the primary chancre, although they can occur months later or even before this sore disappears.2 Secondary syphilis typically presents as maculopapular and erythematous scaling lesions, although lichenoid, nodular, and ulcerated lesions may also be observed, though less frequently.3,4 HIV infection accelerates the progression of syphilis by altering cell-mediated immunity, and it is sometimes associated with atypical syphilis manifestations.4

Known as the great imitator, syphilis is a true diagnostic challenge for clinicians. Although secondary syphilis is known to mimic other diseases (pityriasis rosea, psoriasis,5 sarcoidosis, etc.), lichenoid eruptions are uncommon.6 These eruptions were reported prior to the introduction of penicillin, i.e., when arsenic-based compounds were still being used as the treatment of choice for syphilis, and it was assumed that these compounds for responsible for the lichenoid appearance of the lesions. Similar lesions, however, continued to be observed when they were replaced with penicillin.7 Serology, together with histologic findings, has an important diagnostic role, with positive results shown by both treponemal and nontreponemal tests. Most patients with HIV infection have normal serology, although they may present false-positive nontreponemal responses and higher-than-expected titers in the absence of reinfection. It should also be noted that delayed positives and false negatives are also possible with nontreponemal tests.

The treatment of secondary syphilis in patients with HIV infection has generated some controversy. The latest edition of the Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control8 recommends a single dose of intramuscular benzathine penicillin G 2.4 million units, regardless of whether the patient has concomitant HIV infection or not, as additional doses have not proven to be more effective.

Although the literature contains reports of secondary syphilis mimicking lichen planus, our cases are interesting in that the lesions were exclusively genital. We found only 2 similar cases in our literature search.9 Both clinicians and pathologists should be aware of the highly variable clinical and histologic features of secondary syphilis to ensure prompt diagnosis and treatment.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Jiménez-Gómez N. Sífilis secundaria simulando liquen plano en el paciente con infección por VIH. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2016;107:612–614.