Pityriasis rotunda (PR) is a rare acquired disease of keratinization. It presents as well-defined, scaly round plaques that can be hyper- or hypopigmented. PR mainly affects young adults of African descent and shows no gender preference. It has been associated with systemic diseases and malignant tumors, though many cases present no associated disorders.1 We present a case of intense PR associated with hyperprolactinemia.

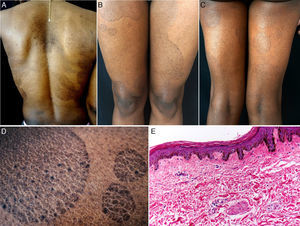

The patient was a 38-year-old African American woman with a history of hyperprolactinemia on treatment with cabergoline for the previous 7 months. She attended dermatology outpatients for a 9-month history of sharply outlined, circumscribed hyperpigmented plaques of ichthyosiform appearance, measuring 3 to 15cm in diameter (Fig. 1). The patient stated that the lesions had first appeared on her chest and that they had gradually increased in size and number, spreading to the abdomen, buttocks, and upper and lower limbs. She reported no associated symptoms or previous treatment. Histopathology revealed hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, a reduction in the granular layer, increased pigmentation of the basal keratinocytes, loss of the crest pattern, and a mild superficial perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate (Fig. 1). The findings were consistent with a diagnosis of PR.

A, Hyperpigmented oval plaques on the back. B and C, Multiple oval lesions on the thighs. D, Close-up image showing ichthyosiform flaking with sharp, well-defined borders. E, Compact hyperkeratosis, thinning of the epidermis, absence of the granular layer, flattening of the epidermal crests, hyperpigmentation of the basal keratinocytes, a mild perivascular infiltrate, and few skin adnexa. Hematoxylin and eosin, original magnification×10.

Laboratory tests including complete blood count, biochemistry, urinalysis, Mantoux test, and tumor markers (α-fetoprotein, Ca 19.9, Ca 125, β2-microglobulin, and carcinoembryonic antigen) were normal or negative. Computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis, upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, and colonoscopy were normal.

After making the diagnosis, treatment was started with 10% salicylic acid cream and a combination of betamethasone plus calcipotriol, which led to a partial response.

PR, a rare disorder of keratinization, was described by Toyoma in 1906 as pityriasis circinata.2 The frequency in the American continent is unknown, but it is considered a common disease in Japan, western India, and South Africa, where the prevalence is of 63 cases per 5800 population. PR affects men and women equally and is most common between the ages of 20 and 45 years.3

The etiology is unknown, though the majority of authors believe PR to be an acquired form of ichthyosis, a late presentation of congenital ichthyosis, or a cutaneous manifestation of systemic diseases such as malnutrition, tuberculosis, cirrhosis, or tumors. It has also been associated with leprosy, lung and liver diseases, multiple myeloma, chronic myeloid leukemia, heart disease, and diabetes.4,5

Concerning the pathogenesis of PR, Makino et al.6 recently described a reduction or absence of expression of filaggrin 2 in the epidermis of PR lesions, similar to the findings in lesions of atopic dermatitis, ichthyosis vulgaris, and psoriasis vulgaris.

Clinically, PR is characterized by the appearance of very well-defined, hyper- or hypopigmented circular plaques of ichthyosiform appearance, with no associated inflammatory signs. Lesions occur on the back, upper and lower limbs, abdomen, and buttocks; their number can vary between 1 and 100,1 and they can persist for months to years, with exacerbations during the winter.4

Various changes can be seen on histopathology, including hyperkeratosis, flattening of the epidermal crests, a reduction or absence of the granular layer, hyperpigmentation of basal layer, mild spongiosis, comedo-like openings, incontinentia pigmenti, and a superficial perivascular infiltrate; the histopathological appearance may even be normal in some cases.1,4

Two subtypes have been proposed. Type 1, common in African American and Asian individuals, is characterized by a small number of hyperpigmented lesions in patients with no family history of the disease and it is associated with malignant and systemic diseases. Type 2, which, in contrast, is more common in white patients with a family history of the disease, presents more numerous, hypopigmented plaques and is not associated with malignant diseases.7 Despite this classification, some reported cases show characteristics of both subtypes.4

The clinical differential diagnosis includes tinea versicolor, tinea corporis, nummular eczema, fixed drug reaction, erythrasma, pityriasis rosea, figurate erythema, and leprosy.1

Treatment is difficult in most cases. Topical corticosteroids, antifungal agents, salicylic acid, topical and oral retinoids, lactic acid lotions, and tars have been used without success.1,4 Recently, treatment with vitamin D3 has produced a gradual improvement in the lesions.6 When an underlying disease is present, its treatment can lead to improvement or even resolution of the PR lesions.8

To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of PR associated with hyperprolactinemia, and we therefore consider its publication important. The finding of this dermatosis should always alert the physician to the possibility of malignancy, systemic diseases, or hormonal disorders.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Pinos-León V, Núñez M, Salazar M, Solís-Bowen V. Pitiriasis rotunda e hiperprolactinemia. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2016;107:535–537.