A new, updated AEDV Psoriasis Group (GPs) consensus document on the treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis was needed owing to the approval, in recent years, of a large number of new drugs and changes in the treatment paradigm.

MethodologyThe consensus document was developed using the nominal group technique and a scoping review. First, a designated coordinator selected a group of Psoriasis Group members for the panel. The coordinator defined the objectives and key points for the document and, with the help of a documentalist, conducted a scoping review of articles in Medline, Embase, and the Cochrane Library up to January 2021. The review included systematic reviews and meta-analyses as well as clinical trials not included in those studies and high-quality real-world studies. National and international clinical practice guidelines and consensus documents on the management of moderate to severe psoriasis were also reviewed. Based on these reviews, the coordinator drew up a set of proposed recommendations, which were then discussed and modified in a nominal group meeting. After several review processes, including external review by other GPs members, the final document was drafted.

ResultsThe present guidelines include general principles for the treatment of patients with moderate to severe psoriasis and also define treatment goals and criteria for the indication of biologic therapy and the selection of initial and subsequent therapies. Practical issues, such as treatment failure and maintenance of response, are also addressed.

La aprobación de un gran número de nuevos fármacos en los últimos años y los cambios en el paradigma de tratamiento de la psoriasis hacen recomendable un nuevo documento de recomendaciones del GPS para el tratamiento de la psoriasis moderada-grave.

MetodologíaPara la elaboración del consenso se siguió la metodología de grupos nominales, con ayuda de una scoping review. Tras designar a un coordinador, se seleccionó un grupo de integrantes del GPS. El coordinador definió los objetivos y puntos clave del documento y, con ayuda de un documentalista, se realizó una scoping review incluyendo datos de Medline, Embase y Cochrane Library (hasta enero del 2021). Se seleccionaron revisiones sistemáticas, metaanálisis y ensayos clínicos no incluidos en las mismas, así como estudios de calidad en vida real. Se revisaron otras guías de práctica clínica y documentos de consenso nacionales e internacionales sobre el manejo de la psoriasis moderada-grave. El coordinador generó una serie de recomendaciones preliminares que fueron evaluadas y modificadas en una reunión de grupo nominal. Tras varios procesos de revisión, que incluyeron la revisión externa por parte de los miembros del GPS, se redactó el documento definitivo.

ResultadosEn el documento se incluyen principios generales sobre el tratamiento de los pacientes con psoriasis moderada-grave, la definición de objetivos terapéuticos y los criterios de indicación y selección de tratamiento tanto en primera como en sucesivas líneas terapéuticas de fármacos biológicos. Se abordan asimismo cuestiones prácticas como el fracaso terapéutico o el mantenimiento de la respuesta.

The Psoriasis Group (GPs) of the Spanish Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (AEDV) launched a project in 2009 to develop and update evidence-based recommendations for the treatment of psoriasis with biologic therapies (including biosimilars and the new generation of synthetic molecules), which would also incorporate proposals derived from clinical practice.1–3 The aim of this consensus statement is to provide dermatologists with a tool for consultation that can support the process of making treatment decisions to ensure that patients with moderate to severe psoriasis receive the best treatment available at any given time. Another objective was to collect and standardize strategies—developed and implemented in clinical practice by dermatologists with expertise in the management of psoriasis who are members of the GPs—that facilitate the treatment of psoriasis, enhancing the patients’ prospects of achieving the best clinical response and the convenience and safety of therapy. To this end, the recommendations cover aspects such as the evaluation of the severity of psoriasis and its practical implications, the prescription of these therapies (first-line and successive treatments), setting treatment goals, and response to treatment.

These recommendations also represent the position, as defined by the GPs, of Spanish dermatologists on the treatment of psoriasis, making them a useful tool for hospital pharmacists, patient associations, hospital managers, and health authorities.

This update incorporates some modifications with respect to previous statements1–3 and new considerations concerning advances in biologic therapies and new international standards derived from accumulated experience.

JustificationThe current therapeutic arsenal for the management of moderate to severe psoriasis is very extensive: phototherapy (psoralen+UV-A [PUVA] and narrow-band UV-B), conventional systemic therapies (ciclosporin, methotrexate, acitretin, and fumarates), the new generation of synthetic molecules (apremilast and shortly deucravacitinib), and biologic therapies including some biosimilars (adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab, certolizumab, ustekinumab, secukinumab, ixekizumab, brodalumab, tildrakizumab, guselkumab, risankizumab and, shortly, bimekizumab). The biologics can be used alone or in combination with topical therapies or conventional systemic drugs.

Advances in the treatment of psoriasis have changed expectations for short- to medium-term efficacy and safety and for maintenance of the treatment response over time. Most guidelines and expert group recommendations are setting increasingly demanding treatment goals, reflecting the results obtained in the randomized clinical trials and their long-term extension studies and supported by evidence from real-life studies.

Given the high cost of the new biologic therapies, non-clinical stakeholders, such as managers and health care payers, now play a significant role in the decision-making process. The advent of biosimilars represents an opportunity to expand access to biologic therapies and to increase the efficiency of these treatments.4,5 However, the incorporation of biosimilars into first-line treatment has often led to the use of absolute cost of acquisition as the fundamental criteria for prioritizing treatments, a formula that can give rise to marked variations between regional health services and problems of equity.6 Treatment appraisal reports have imposed reimbursement conditions and mandatory prior treatment with a TNF-α inhibitor in the case of some innovative drugs for the treatment of psoriasis, including guselkumab, risankizumab, and tildrakizumab. These requirements are not supported by the available evidence and are not even consistent with the conclusions of the reports themselves. The GPs has called attention to the need for greater independence, transparency, consistency, and pharmacoeconomic documentation (incremental cost per responder, modeling with a time horizon) in the preparation of documents used by health care payers. This approach is key to ensuring that these decisions really incorporate efficiency as an objective and measurable parameter, in line with common practice in other European countries.7

An updated GPs consensus document on the treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis was needed because of changes in the treatment paradigm and the approval of a large number of new biologic agents, including biosimilars, and new generation synthetic molecules.

MethodologyStudy DesignThis consensus document was developed by the GPs of the AEDV. It was developed using the nominal group technique complemented by a scoping review. The process used was fully compliant with the principles for medical research in humans set out in the most recent version of the Declaration of Helsinki and was implemented in accordance with the applicable regulations on good clinical practice.

Participant Selection and Development of the Consensus StatementFirst, a designated coordinator was appointed and a group of GPs members were selected for the panel based on their experience and knowledge of psoriasis. The coordinator, with the help of a methodologist, then defined the objectives, sections, and scope of the document, including a definition of its target audience. Finally, a scoping review was conducted given the volume of publications on the efficacy and safety of biologic therapies for the treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis, including biosimilars and new generation synthetic molecules. The scoping review was conducted with the help of an expert documentalist, who designed several strategies based on MeSH terms and free-text terms to search the three major bibliographic databases (Medline, Embase, and the Cochrane Library) up to January 2021. The review included systematic reviews and meta-analyses as well as randomized clinical trials (RCTs) not included in those studies and high-quality real-world studies. National and international clinical practice guidelines and consensus documents on the management of moderate to severe psoriasis were also reviewed.

Based on the results of this review, the coordinator drew up a draft text and a set of preliminary recommendations, which were then evaluated, discussed and modified in a nominal group meeting. The final document was drafted after several review processes, including external review by the GPs members.

ResultsEvaluation of Disease Severity in PsoriasisSeveral validated measures are used universally in clinical practice to assess disease severity in patients with psoriasis. The most used are the percentage of the body surface area affected (BSA), the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI), and global assessment by either the physician (PGA) or patient (PtGA).8 In previous consensus statements, the GPs considered the absolute PASI score to be the most useful measure for assessing whether the patient's response to treatment was within the desired parameters at any time during the course of the disease.1,2

The Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) is the tool most used by dermatologists to measure health-related quality of life in patients with psoriasis. Although easy to use and sensitive to change, this index is limited by its unidimensional structure and variable cross-cultural equivalence.9

Psoriasis is a disease that has a major impact on the whole course of the patient's life. The lifelong impact of the disease is captured by the concept of Cumulative Life Course Impairment (CLCI).10 When making clinical assessments and taking decisions about management of the disease, clinicians should evaluate not only the current but also the potential future impact of the disease on each patient by taking into account sociodemographic factors (e.g., age and gender) as well as clinical variables, such as disease severity and comorbid conditions, which have been identified in a recent systematic review as risk factors for CLCI.11

The location of lesions, associated symptoms, impact on quality of life, and resistance to treatment are other aspects that we will consider in the context of making decisions on the management of moderate to severe psoriasis.3

Classification of Moderate to Severe Psoriasis And Criteria for Systemic TreatmentThe GPs criteria for classifying moderate to severe psoriasis were established in 2009 and ratified in 2016 (Table 1).1–3 These criteria represented a qualitative leap because they included, in addition to the parameters accepted by most scientific societies and considered to be objective (although some, such as the rule of tens, are arbitrary), clinical manifestations considered to be criteria for severity owing to their characteristics, extent, location, or association with joint involvement. However, probably the most innovative change was the incorporation of the need for systemic treatment or phototherapy as a criteria defining moderate to severe psoriasis, and, thereby its inclusion as another factor to be taken into account in the decision making process. Similar proposals have also been made by other scientific societies.12–15

Criteria for Moderate to Severe Psoriasis in the AEDV Psoriasis Working Group 2009 and 2016 Consensus Documents.a

| # | Criteria for moderate to severe psoriasis |

|---|---|

| 1 | PASI>10 or BSA>10 or DLQI>10 |

| 2 | Psoriasis requiring systemic treatment at any time (including conventional systemic treatment, biologics, and phototherapy) |

| 3 | Erythrodermic psoriasisb |

| 4 | Generalized pustular psoriasisb |

| 5 | Localized pustular psoriasis causing functional or psychological limitationsb |

| 6 | Psoriasis affecting visible areas (e.g. the face), palms, soles, genitals, scalp, nails, or recalcitrant plaques when these have a functional or psychological impact on the patient |

| 7 | Psoriasis associated with psoriatic arthritis |

Abbreviations: AEDV, Spanish Academy of Dermatology and Venerology; BSA, body surface area; DLQI, Dermatology Life Quality Index; PASI, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index.

The purpose of tools that measure the severity of psoriasis is to facilitate the management of the disease and to achieve the best outcomes for the patient in every situation. In this setting, the GPs proposes that the following patients should be considered to be candidates for systemic treatment, including biologic therapies:

- 1.

Patients who meet at least 1 of the following criteria: BSA 10% or PASI>10 or DLQI>10.

- 2.

Disease affecting visible areas (face and dorsum of hands), palms, soles, genitals, scalp, nails, and also recalcitrant plaques with a functional or psychological impact.

- 3.

Psoriasis that is not controlled by topical therapy orphoto-therapy.

This approach includes the failure of properly implemented topical therapy as a criterion comparable to the extent or location of lesions in the decision to prescribe systemic treatment. The choice of systemic treatment is based on the general considerations discussed earlier in this document and on the indications in the Summary of Product Characteristics and the criteria for approval of systemic treatment by the regulatory agencies for all available therapies. This proposal is also in line with the approach approved through consensus by international organizations, such as the International Psoriasis Council.12

General Principles for the Management of Patients with Moderate to Severe PsoriasisAll the biologic therapies (including biosimilars) and new generation synthetic molecules that have demonstrated efficacy and safety and have been approved by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) can be prescribed in routine clinical practice and dermatologists should be able to prescribe therapies as indicated in the Summary of Product Characteristics for each drug without any delays or restrictions, which could give rise to inequities between different regions or hospitals. These therapies should be prescribed by dermatologists with experience in their use, who can evaluate and take into account all the variables to optimize the decision making process and ensure the best possible clinical results in terms of efficacy and safety.

Several factors must be taken into account when selecting or prioritizing these therapies:

- –

Related to the drug: available evidence (short- and long-term efficacy, maintenance of response, better efficacy in direct and indirect comparisons between drugs in meta-analyses, safety, efficiency), route of administration, speed of onset of effect, convenience.

- –

Related to the patient and the disease: the type, course, severity, and extent of disease, its impact on the patient's quality of life and symptoms, prior therapies and adherence to treatment, age, sex, weight, and the presence of comorbidities, especially psoriatic arthritis.

- –

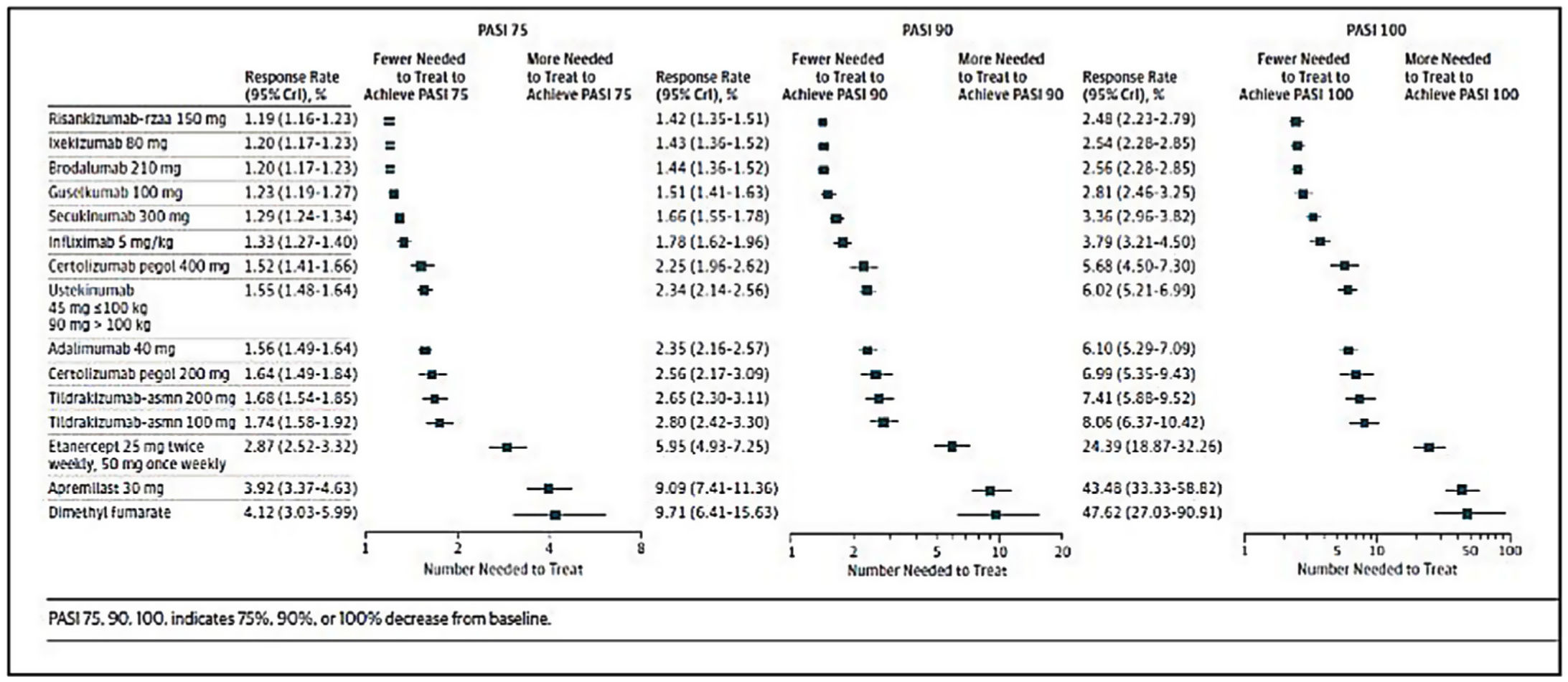

Related to the health system and its organization: results of cost-effectiveness studies. GPs recommends that the following parameter should be evaluated as part of any prioritization by efficiency criteria: number needed to treat (NNT), always taking as a reference the generally accepted clinical endpoints (e.g. PASI 90 and PASI 100 response and absolute PASI score<3). Prioritization by cost of acquisition is considered arbitrary if not supported by the evaluation of efficiency criteria to demonstrate real efficiency.

The final decision about which drug to prescribe should be left to the clinical judgment of the dermatologist, who will make a well-founded decision after assessing the above criteria and applying them to the case under consideration.

Treatment Goals for Patients with Moderate to Severe PsoriasisThe clinical assessment of patients with psoriasis is an essential component of the process of making decisions about treatment. It informs the setting of a treatment goal (which in turn guides the selection of a specific therapy for each patient) and facilitates monitoring of the treatment response. Disease activity is a fundamental aspect of the clinical assessment in psoriasis. Despite its limitations, the PASI is the accepted standard for evaluating disease activity and should be assessed at every visit. Measures of relative improvement, such as PASI 90 (90% improvement over baseline) are appropriate for assessing response to treatment in RCTs and for direct and indirect comparisons. However, GPs considers the absolute PASI score to be a more useful measure than relative PASI when assessing severity in clinical practice for the purpose of setting a treatment goal and measuring response to treatment because it is independent of the baseline PASI value. DLQI, BSA, and PGA can be used to complement the PASI when deciding on a treatment strategy. When the PGA is used, BSA should always be calculated as well. A visual analog scale to assess itching and patient satisfaction with treatment can be included in the assessment of the impact on quality of life.16 PGA should be used to assess psoriasis involving special areas (genitalia, scalp, palms and soles) and the Nail Psoriasis Severity Index (NAPSI) when there is nail involvement because the PASI is not an appropriate tool for evaluating such lesions.

New drugs and new evidence on the effectiveness of therapies17–22 have emerged since the publication of the GPs guidelines and recommendations in 2009, 2013, and 2016,1–3 further raising expectations regarding treatment outcomes in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis. Several studies (especially those involving recently introduced drugs) have shown that a relatively high percentage of patients with moderate to severe psoriasis can achieve complete clearance. At 16 weeks, PASI 100 responses ranging from 13.7% to 57.2% have been reported depending on the drug.23–85

Given the clinical heterogeneity of psoriasis and the variability of response to treatment, the GPs believes that in the current management of patients with moderate to severe psoriasis, optimal or ideal treatment objectives and clinically acceptable goals can be established for each patient (Table 2).

Updated Recommendations (2021) on Setting Treatment Goals in Moderate to Severe Psoriasis.

| # | Recommendations |

| 1 | Treatment goals should be:∘Individualized∘Adapted to the characteristics of the patient's disease in each case∘Adapted to the individual characteristics of the patient∘Established independently of the class of drug |

| 2 | When setting treatment goals, the clinician should differentiate between:∘Optimal goals∘Clinically acceptable goals |

| 3 | Optimal treatment goals should include:∘Achieving a PASI 100 response, absolute PASI score of 0, or complete clearance∘Absence of clinical signs or symptoms of psoriasis∘Absence of any impact on the patient's psychological, emotional, social, or occupational well-being. |

| 4 | Clinically acceptable goals should include:∘Achieving a PASI 90 response∘Achieving an absolute PASI score of ≤3∘BSA<3% and PGA 0–1∘In special areas: PGA≤1∘Minimize the impact of disease on quality of life∘Reduce disease activity to a minimum∘A DLQI of 0/1 assessed independently of clinical response is not an appropriate treatment goal. |

| 5 | In specific patients or situations (prior treatment failure, associated comorbid conditions), other treatment goals can be considered clinically acceptable (a PASI 75 response, an absolute PASI score of ≤5) |

Abbreviations: BSA, body surface area; DLQI, Dermatology Life Quality Index; PASI, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index; PGA, Physician Global Assessment.

For establishing optimal and clinically acceptable treatment goals, the GPs recommends the use of the PASI, and preferably the absolute score, although PASI response relative to baseline is also acceptable. Despite the limitations of the PASI,8,86–95 there are several factors in its favor: its generalized use, the correlation between an absolute PASI score<2–3 and a PASI 90 response and between PASI 90 and DLQI 0/1, and the recommendations of recent international guidelines and recommendations.96–108

Another change from earlier GPs consensus documents1–3 relates specifically to optimal treatment targets. For the first time, based on new evidence,23–85 complete clearance—defined as an absolute PASI score of 0 or a PASI 100 response—have been included among the optimal treatment goals, recognizing that these outcomes are now achievable in at least a subgroup of patients. Clinically acceptable treatment goals have also changed. Based on current evidence,23–85 the upper limit for these goals has been increased to include a PASI 90 response and an absolute PASI≤2–3 (the goals specified in earlier guidelines were a PASI 75 response and an absolute PASI≤5).1 Nevertheless, the GPs recognizes there are scenarios in clinical practice—particularly among patients whose condition, for whatever reason, has not responded to several biologic therapies—in which less demanding treatment goals may be acceptable and in which a PASI 75 response or an absolute PASI score of ≤ 5 may be adequate.

On the other hand, the clinician should also evaluate—and take into account in the decision making process—the impact in terms of quality of life, safety, and efficiency of trying to achieve a PASI 100 response or and absolute PASI score of 0 in all patients.

As an alternative to the above, another method of assessing disease activity is the concept of minimal disease activity (MDA), which the GPs has defined as the absence of active arthritis and at least 3 of the following criteria109,110:

- –

Itching≤1/10

- –

Scaling≤2/10

- –

Erythema≤2/10

- –

Visibility≤2/10

- –

BSA≤2

- –

DLQI≤2

- –

No lesions in special areas

Infliximab, etanercept, and ustekinumab are indicated in patients who have intolerance or contraindications to other systemic treatments, such as methotrexate and PUVA. According to their respective Summaries of Product Characteristics, the rest of the biologic therapies approved for psoriasis are indicated as first-line therapy for patients with psoriasis who are candidates for systemic treatment (Table 3).

Indications for Biologic Drugs in Different Subpopulations.

| Drug | Indication as per summary of product characteristics (EMA) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psoriasis in adults | Psoriasis in children | Psoriatic arthritis | Pregnant women | |

| Infliximab | Adults who failed to respond to, have a contraindication to, or are intolerant to other systemic therapies, including ciclosporin, MTX and PUVA | – | Adults with active psoriatic arthritis who have an inadequate response to or intolerance to DMARDs | Certolizumab pegol approved |

| Etanercept | Chronic severe plaque psoriasis in children and adolescents from 6 years of age who are inadequately controlled by or are intolerant to other systemic therapies or phototherapies | |||

| Ustekinumab | Moderate to severe plaque psoriasis in adolescents from 12 years of age who have responded inadequately to, or are intolerant to, other systemic therapies or phototherapies. | |||

| Apremilast | – | |||

| Adalimumab | Adults who are candidates for systemic treatment | Severe chronic plaque psoriasis in children and adolescents from 4 years of age who have had an inadequate response to, or are inappropriate candidates for, topical therapy and phototherapy | ||

| Certolizumab pegol | – | |||

| Ixekizumab | Moderate to severe plaque psoriasis in children from the age of 6 years with a body weight of at least 25kg and in adolescents who are candidates for systemic therapy | |||

| Secukinumab | Moderate to severe plaque psoriasis in children and adolescents from the age of 6 years who are candidates for systemic therapy | |||

| Brodalumab | – | – | ||

| Guselkumab | – | – | ||

| Risankizumab | – | – | ||

| Tildrakizumab | – | – | ||

Abbreviations: DMARDS, disease modifying antirheumatic drugs; EMA, European Medicines Agency; MTX, methotrexate; PUVA, psoralen plus UV-A photochemotherapy.

In the Spanish public health system, the cost of treatment with guselkumab, risankizumab, and tildrakizumab is only reimbursed if the patient has previously received treatment with a TNF-α inhibitor. This restriction (included in the final remarks made by the treatment appraisal working group) is arbitrary and has no basis in the text of the treatment appraisal report itself, which proposes that the decision on therapy should be based on efficiency criteria.

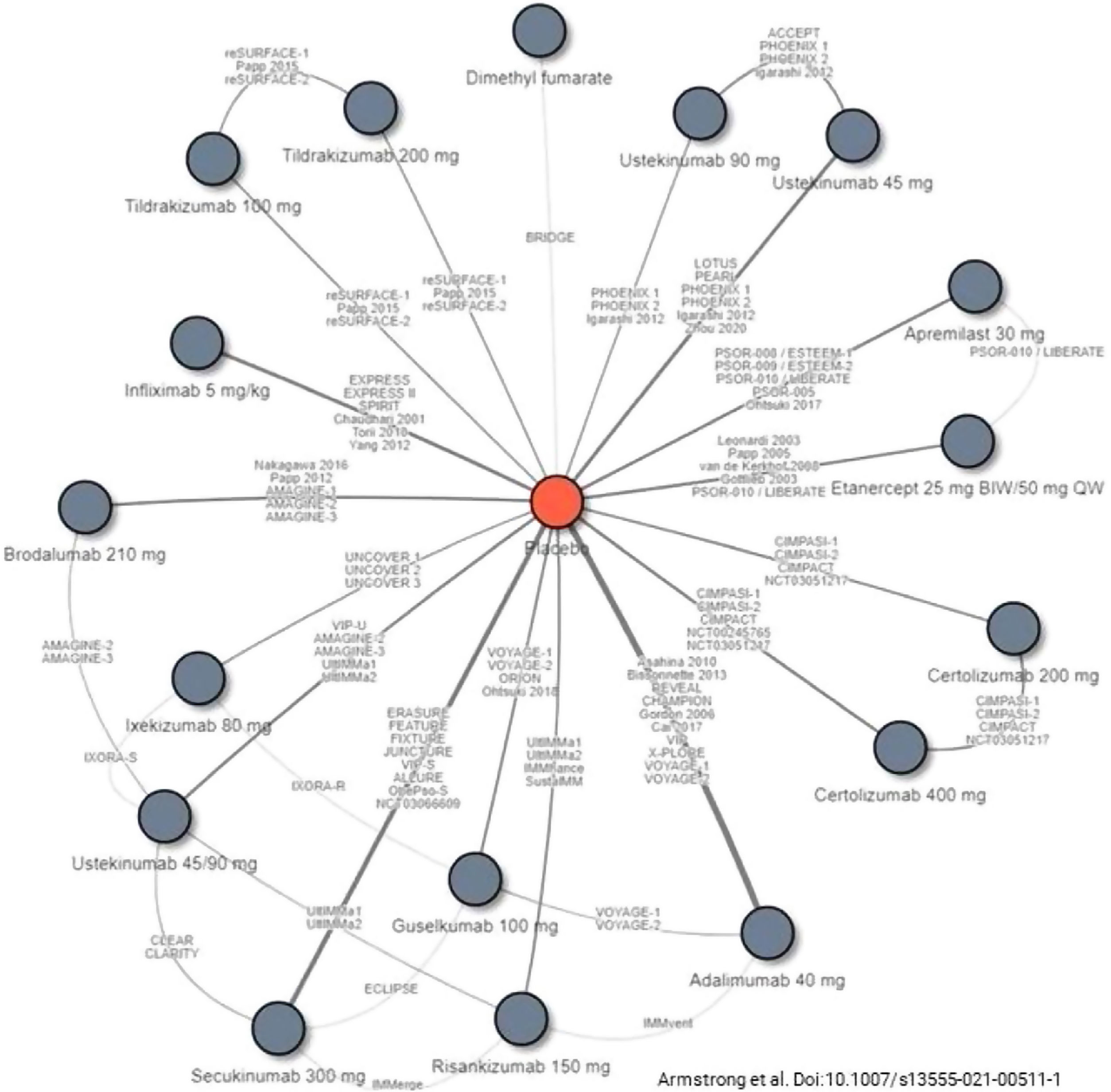

Decisions on first-line biologic therapy (including biosimilars and new generation synthetic molecules) should be made based on the general principles described above. The GPs recommends that prescribers should evaluate the pertinent review articles and network meta-analyses17,19,21,111–114 (see Figs. 1 and 2) to inform their decisions on the choice of therapy, depending on the treatment goals recommended. The following considerations should also be taken into account:

- –

Given their favorable safety profile and efficacy in direct and indirect comparisons with other drugs, drugs targeting interleukin (IL)-17 and its receptor or IL-23 (anti-p19) offer, on the whole, the best prospects for achieving the treatment goals set out in this document.

- –

Other classes of drugs, including TNF-α inhibitors and drugs targeting IL-12/23 (anti-p40), may be considered to be the most indicated therapies for first-line treatment in certain patients and clinical scenarios.

- –

Based on efficiency criteria, biosimilars of any class emerge as the most indicated therapies for first-line treatment (provided there are no contraindications or safety considerations in the case of the individual patient) provided that the decision is based on studies or assessments that demonstrate their efficiency.

- –

When taking a decision on the best treatment for a particular patient, the clinician should also take into account the impact the selected therapy may have on psoriatic arthritis.

- –

Comorbid conditions—such as inflammatory bowel disease, fatty liver disease, cardiovascular disease, or demyelinating disease—may influence or condition the choice of treatment, owing to safety issues in certain cases.

Studies included in a recent network meta-analysis of biologic therapies, including biosimilars and new generation synthetic molecules, currently approved for the treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis.

Source: Armstrong et al.114

Additional number of patients needed to treat, relative to placebo, to achieve a PASI 75, PASI 90, or PASI 100 response, estimated in a recent network meta-analysis of biologic therapies and new generation synthetic molecules currently approved for the treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis. PASI, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index.

Source: Armstrong et al.113

The safety profile of biologic therapies should also be taken into account when selecting a treatment (see risk management section below).17,19,21,111,112 There is, however, still insufficient long-term data on safety available for the drugs approved in recent years.

Single-Drug Therapy vs. Combination TherapyThe GPs recommends the use of biologic therapies as single-drug therapy. However, regimens combining biologic agents with conventional systemic drugs, phototherapy, or topical treatments can be considered depending on the patient characteristics and the disease characteristics, preferably intermittently or in the short-term. There is no consistent evidence that combination therapy is clearly more effective than single-drug therapy.115,116 Moreover, the use of combinations may increase the risk of toxicity.115 Combining certain biologic drugs with methotrexate may decrease or minimize the risk and impact of immunogenicity, but the evidence available only relates to combinations of methotrexate with infliximab or adalimumab.115,117

Presence of Comorbid ConditionsIn recent years, several authors have described the potential effects of certain therapies or classes of drugs on comorbidities related to low-grade inflammation. Although there is evidence that some of these drugs improve cardiovascular risk parameters,118–120 it is currently not sufficient to prioritize one drug over another on this basis.121 New evidence may change this view.

Dermatologists should take psoriatic arthritis into account when taking decisions about treatment.

Concept of Treatment FailureThe current consensus proposes eliminating the concept of rebound, which was included in the 2016 GPs statement,1 because the rebound effect does not influence therapeutic decisions in routine clinical practice.

In this 2021 update, the GPs considers a treatment to have failed when any of the following conditions are met:

- –

The desired treatment goal is not achieved after 16–24 weeks of treatment (the induction phase): primary treatment failure.

- –

The treatment goal is initially achieved but subsequently lost during the maintenance phase: secondary treatment failure.

- –

The treatment goal is achieved, but the therapy results in significant toxicity that requires cessation of treatment: failure due to safety issues.

The GPs also emphasizes the importance of assessing patient adherence to treatment before making a decision on whether or not treatment has failed.122

Indication and Selection of Therapy for Second and Subsequent Lines of TreatmentWhen a patient with moderate to severe psoriasis does not respond to biologic therapies, including biosimilars and new generation synthetic molecules, the GPs recommends any one the following options:

- –

Switching to another biologic therapy, including biosimilars and new generation synthetic molecules.

- –

In certain cases, the following may be considered:

- 1.

Combinations with other conventional systemic treatments or topical treatments, preferably on an intermittent or short-term basis.

- 2.

Dose increase/interval shortening (for drugs where this is permitted). In such cases, the clinician must take into account the safety and efficiency considerations in the drug's Summary of Product Characteristics.

- 1.

The selection of the second and successive lines of treatment with biologic therapies, including biosimilars and new generation synthetic molecules, depends on all the factors mentioned in the general principles described above and should also take the following into account:

- –

The evidence (efficacy and safety) is currently limited (especially as the number of treatment lines increases).

- –

In cases of patients with primary treatment failure (when the treatment goal is not reached at any time) or secondary failure (the desired response is achieved but subsequently lost), drugs having the same mechanism of action or an alternative mechanism of action may be used.

- –

In the case of primary failure, a change of mechanism of action/therapeutic class is recommended.

- –

When treatment failure is due to a significant adverse event related to the drug class, a change of mechanism of action/therapeutic class should be considered.

- –

There is no data on the effect of previous treatment failures on the success of any particular subsequent line of treatment.

- –

In certain cases, such as patients with specific comorbidities or prior failure to respond adequately to a number of biologic therapy regimens, flexibility in the treatment goals is advisable. The criteria for an adequate response should be individualized in patients who have failed to respond to multiple therapies.

Table 4 summarizes the available evidence on the main outcomes achieved after a switch in therapy.

Summary of Available evidence on PASI 75, PASI 90, and PASI 100 Response after Switching a Biologic Drug.

| Drug | Study design | Prior biologic therapy | Week | PASI 75 (%) | PASI 90 (%) | PASI 100 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TNF-α inhibitors | ||||||

| Etanercept | Registry (n=23)124 | Infliximab or adalimumab | 1624 | 1424 | – | – |

| Open prospective, (n=27)125 | Infliximab or efalizumab | 24 | 65.2 | – | – | |

| Adalimumab | Open prospective, (n=85)126 | Etanercept | 1224 | 40a31b52a63b | – | – |

| Registry (n=30)127 | Etanercept | 1224 | 2736 | – | – | |

| Registry (n=43)124 | Etanercept or infliximab | 1624 | 3858 | – | – | |

| Retrospective128 | Any TNF-α inhibitor (n=52) | 122412 | 56.982.743.4 | 3451.930.2 | 24.544.222.6 | |

| Ustekinumab (n=53) | 24 | 71.4 | 55.1 | 40.8 | ||

| Prospective cohort (n=29)129 | Secukinumab | 52 | 75.9 | 15.4 | 3.85 | |

| Infliximab | Registry (n=39)124 | Etanercept or adalimumab | 1624 | 2740 | – | – |

| Open prospective, (n=215)130 | Etanercept | 10 | 52 | – | – | |

| Open Prospective, (n=38)131 | Etanercept | 101824 | 719474 | – | – | |

| IL-23 inhibitors | ||||||

| Guselkumab | Voyage 1 (RCT)132 | Adalimumab | 100 | – | 81.1 | 51.6 |

| Voyage 2 (RCT)132 | Adalimumab | 100 | – | 81.4 | 51.4 | |

| ECLIPSE (RCT)133 | TNF-α inhibitor IL-12/23, IL-23 inhibitorIL-17 inhibitor (excluding secukinumab) | 484848 | – | 76.873.385.5 | 57.355.659.4 | |

| Risankizumab | LIMMitless (extension)134 | Ustekinumab | 84 | – | 82.6 | 44.8 |

| UltIMMa-1,2 (RCT)135 | TNF-α inhibitorIL-17 inhibitor | 5252 | – | 81.378.4 | –– | |

| IMMvent (RCT)136 | Adalimumab | 44 | – | 6 | – | |

| IL-17/IL-17i inhibitors | ||||||

| Secukinumab | ECLIPSE (RCT)133 | TNF-α inhibitor | 48 | – | – | 42.4 |

| IL-12/23, IL-23 inhibitor | 48 | 40.9 | ||||

| IL-17 inhibitor (excluding secukinumab) | 48 | 52.2 | ||||

| Ixekizumab | Retrospective (n=31)137 | Secukinumab | 12 | 71 | ||

| Retrospective (n=69)138 | Secukinumab | 1224 | 81.180 | 72.468 | 40.538 | |

| Retrospective (n=17)139 | Secukinumab | 12 | 88.2 | – | – | |

| Retrospective (n=18)140 | Secukinumab | 12 | 50 | – | – | |

| Brodalumab | AMAGINE-2,3 (RCT)43 | Ustekinumab | 52 | 91, 87 | – | 46, 40 |

| Open prospective, (n=39)141 | Secukinumab o ixekizumab | 16 | 67 | 44 | 28 | |

| Retrospective (n=23)142 | Secukinumab or ixekizumab | 12 | 47.8 | – | – | |

| Retrospective143 | Secukinumab (n=7) ixekizumab (n=3) | 12 | 67 | – | – | |

| IL-12/23 inhibitor | ||||||

| Ustekinumab | UltIMMa-1,2 (RCT)135 | TNF-α inhibitorIL-17 inhibitor | 5252 | – | – | – |

| ACCEPT (RCT)144 | Etanercept | 12 | – | 23.4 | – | |

| Retrospective (n=21)145 | Secukinumab | 48 | 69.2 | 50 | – | |

| Prospective cohort (n=21)129 | Secukinumab | 52 | 85.7 | 19.1 | 4.8 | |

Abbreviations: IL, interleukin; PASI, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index; RCT, randomized controlled trial; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

a Study group A

b Study group N

The evidence available on third lines of treatment is currently very scant and of only moderate-to-low quality. It comes from a few subanalyses of RCT results and observational studies.45,146–150

Although the actions and criteria for the selection of a third-line treatment are the same as those described for the first and second lines, the GPs considers that each time a treatment fails it is vital to reassess the treatment goals and that it is increasingly difficult to achieve optimal or even acceptable results in the case of third and successive lines of treatment. Consequently, treatment goals can be individualized in patients who have experienced several treatment failures, taking into account the characteristics of past failures.

Response MaintenanceThe GPs consensus on the maintenance of response is as follows:

- –

Patients who achieve an optimal or clinically adequate response are considered to be responders and treatment should be maintained.

- –

In routine clinical practice, when the treatment goals (whether optimal or clinically acceptable) are met over a sustained period (6 months to 1 year) in a patient with moderate to severe psoriasis, a change in the treatment strategy can be considered, which may take the form of a reduction in the dose or an increase in the interval between doses.

- –

Treatment reduction protocols (increased interval or reduced dose) should be implemented gradually with close monitoring of the maintenance of the treatment goal. There is no solid evidence to indicate the best strategy for optimizing the results of a reduction in treatment. However, in clinical practice, the interval between doses is generally increased cautiously (30–50%) following easy-to-remember guidelines: for example, an increase to 5–6 weeks for drugs administered every 4 weeks or to 10–16 weeks for drugs administered every 8 or 12 weeks. Each change in interval should be followed up at 1 or 2 follow-up visits to monitor clinical progress before any further changes are made.

- –

If the desired response is lost when the dosage is reduced, the regimen that originally achieved the treatment goal should be reinstated.

- –

Continuous therapy is required to maintain the response over time in most patients. However, when the patient's condition continues to meet the treatment goal on the reduced dosage, withdrawal of treatment can be considered. The GPs would like to point out that there is no clear evidence on how many patients will experience a relapse or exacerbation when the dosage is reduced or on the response that can be achieved if the original treatment is reintroduced. There is evidence in the literature that some patients may not regain the level of response they achieved prior to withdrawal of treatment.82,151–155

- –

When the patient's condition no longer meets the treatment goal following cessation of treatment, a return to the regimen that achieved that goal should be considered.

The rapid evolution of the concept of psoriasis and of the therapeutic arsenal for this skin disease demands a flexible and continuous adaptation of the disease's definition and of the practical recommendations for dermatologists involved in its management. In recent years, the inclusion of the impact of psoriasis on quality of life has led to the relativization of earlier classification criteria and to the search for more practical definitions that can be adapted to the majority of patients. The rapidly evolving situation regarding the efficacy and safety of treatment, owing to changes in our knowledge and understanding of the disease, also justifies the establishment of more demanding goals for clinical outcomes, reflecting the improved prospects of treatment with new classes of drugs. The advent of biosimilars is an opportunity to bring biologic therapy to a larger number of patients with severe to moderate psoriasis, and there is no doubt that this class of drugs as a whole represents a qualitative leap in treatment over classic conventional therapy. At the same time, the advent of biosimilars and the financial implications of their introduction also poses certain risks in the application of the clinical criteria and in terms of equity. These risks must be minimized to favor the evaluation of efficiency. Finally, the consideration of psoriasis as a systemic disease and the importance of assessing comorbid conditions are also an integral part of the therapeutic decision making process and the definition of clinical response.

FundingThis is an independent document authored by the GPs. The GPs received no funding to support the development of this consensus statement.

Conflicts of InterestJosé Manuel Carrascosa has served as a PI/SI and/or received honoraria as a speaker and/or member of an expert or steering committee for Abbvie, Novartis, Janssen, Lilly, Sandoz, Amgen, Almirall, BMS, Boehringer Ingelheim, Biogen, and UCB.

Laura Salgado-Boquete has served as a PI/SI and/or received honoraria as a speaker or for serving on an expert committee or as scientific advisor for Abbvie, Celgene, Leo Pharma, Novartis, Janssen, Lilly, Sandoz, Amgen, Almirall, UCB, Pfizer, and MSD.

Lluis Puig has served as a PI/SI and/or received honoraria as a speaker or for serving on an expert committee or as a scientific advisor for Abbvie, Almirall, Amgen, Baxalta, Biogen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, Gebro, Janssen, JS BIOCAD, Leo-Pharma, Lilly, Merck-Serono, MSD, Mylan, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, Roche, Sandoz, Samsung-Bioepis, Sanofi, and UCB.

Elena del Alcázar has served as a PI/SI and/or received honoraria as a speaker for Abbvie, Almirall, Amgen, Celgene, Janssen, Leo-Pharma, Lilly, Novartis, Sanofi, and UCB.

Isabel Belinchón has served as a PI/SI and has received honoraria as a speaker or scientific advisor or for serving on an expert committee for Abbvie, Almirall, Amgen, BMS, Celgene, Janssen, Lilly, Leo-Pharma, Novartis, and UCB.

Pablo de la Cueva has served as an advisor and/or speaker for and/or has participated as an investigator in trials sponsored by the following pharmaceutical companies: Abbvie, Almirall, Amgen, Astellas, Biogen, BMS, Boehringer, Celgene, Gebro, Janssen, LEO Pharma, Lilly, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Sandoz, Sanofi, and UCB.

David Moreno has participated as PI or Co-PI in clinical trials sponsored by Lilly, Novartis, Amgen, Almirall, Boehringer, and Leo-Pharma.

Juan José Andrés Lencina has served as a PI/SI and/or has received honoraria as a speaker and/or member of an expert committee or an scientific advisor for Abbvie, Leo Pharma, Novartis, Janssen, and UCB.

The authors wish to thank the following members of the GPs for their contribution to this document: M. Teresa Abalde Pintos, Ignacio Alonso García, María Luisa Alonso Pacheco, Alsina Gibert Mercé, Gloria Aparicio Español, Mariano Ara Martín, Susana Armesto Alonso, Antoni Azón Masoliver, Ferrán Ballescá López, Ofelia Baniandres Rodríguez, Didac Barco Nebreda, Alvaro Barranquero Fernández, Ana Batalla Cebey, Isabel Bielsa Marsol, Xavier Bordas Orpinell, Leopoldo Borrego Hernando, Rafael Botella Estrada, Jesús María Careaga Alzaga, Rafael Carmena Ramón, Gregorio Carretero Hernández, Ana María Carrizosa Esquivel, Jose Manuel Casanova Seuma, Alberto Conde Taboada, Marisol Contreras Stelys, Pablo Coto Segura, Esteban Daudén Tello, Carlos de la Torre Fraga, Rubén del Río Gil, Aleisandre Docampo Simón, Noemí Eiris Salvado, Juan Escalas Taberner, Esther Eusebio Murillo, Jose Manuel Fernandez Armenteros, Emilia Fernandez López, M. Luisa Fernández Díaz, Almudena Fernández Orland, Carlos Ferrándiz Foraster, Marta Ferrán Farrés, Lara Ferrándiz Pulido, Eduardo Fonseca Capdevila, Manuel Galán Gutiérrez, Francisco Javier Garcia Latasa de Araníbar, Pilar Garcia Muret, Vicente Garcia-Patos Briones, Marta García Bustínduy, Ignacio García Doval, Rosa García Felipe, Alicia L. González Quesada, Beatriz González Sixto, Alfonso González Morán, Teresa Gárate Ayastui, Francisco José Gómez García, Jose Manuel Hernanz Hermosa, M. Isabel Hernández García, Pedro Herranz Pinto, Enrique Herrera Ceballos, Marta Herrera Sánchez, Rafael Jesús Jiménez Puya, Enrique Jorquera Barquero, Rosario de Fátima Lafuente Urrez, Salvador V. Laguarda Porter, Mónica Larrea Garcia, M. del Mar Llamas Velasco, Anna López Ferrer, Jesús Luelmo Aguilar, Pablo Lázaro Ochaita, Jose Luis López Estebaranz, María Marcellán Fernández, Amparo Marquina Vila, Eugenio Marrón Moya Servando, Trinidad Martin González, Antonio Martorell Calatayud, Francisco Javier Mataix Díaz, Almudena Mateu Puchades, Carolina Medina Gil, M. Victoria Mendiola Fernández, Miren Josune Michelena Eceiza, Jordi Mollet Sánchez, José Carlos Moreno Giménez, Carlos Muñoz Santos, Antoni Nadal Nadal, Belén Navajas Pinedo, Jaime Notario Rosa, Francisco Peral Rubio, Narciso Perez Oliva, Celia Posada García, Josep A. Pujol Montcusi, Conrado Pujol Marco, Silvia Pérez Barrio, Amparo Pérez Ferriols, Beatriz Pérez Suárez, Trinidad Repiso Montero, Miquel Ribera Pibernat, Raquel Rivera Díaz, Vicente Rocamora Durán, Jesús Rodero Garrido, Sabela Rodríguez Blanco, M. del Carmen Rodríguez Cerdeira, Lourdes Rodríguez Fernández-Freire, Manuel Ángel Rodríguez Prieto, Jorge Romani de Gabriel, Alberto Romero Maté, Mónica Roncero Riesco, Cristina Rubio Flores, José Carlos Ruiz Carrascosa, Diana Patricia Ruiz Genao, Ricardo Ruiz Villaverde, Montserrat Salleras Redonnet, Jorge Santos-Juanes Jiménez, María José Seoane Pose, Patricia Serrano Grau, Estrella Simal Gil, Caridad Soria Martínez, José Luis Sánchez Carazo, Manuel Sánchez Regaña, M. Dolores Sánchez-Aguilar Rojas, Rosa Taberner Ferrer, Lucía Tomás Aragonés, Francisco Valverde Blanco, Ricardo Valverde Garrido, Francisco Vanaclocha Sebastián, Manel Velasco Pastor, Diana Velázquez Tarjuelo, Asunción Vicente Villa, David Vidal Sarró, Jaime Vilar Alejo, Eva Vilarrasa Rull, Marta Vilavella Riu, Rosario Vives Nadal, Hugo Alberto Vázquez Veiga, Juan Ignacio Yanguas Bayona, Ander Zulaica Garate.