Since its inception, the Psoriasis Group (GPs) of the Spanish Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (AEDV) has worked to continuously update recommendations for the treatment of psoriasis based on the best available evidence and incorporating proposals arising from and aimed at clinical practice. An updated GPs consensus document on the treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis was needed because of changes in the treatment paradigm and the approval in recent years of a large number of new biologic agents.

MethodologyThe consensus document was developed using the nominal group technique complemented by a scoping review. First, a designated coordinator selected a group of GPs members for the panel based on their experience and knowledge of psoriasis. The coordinator defined the objectives and key points for the document and, with the help of a documentalist, conducted a scoping review of articles in Medline, Embase, and the Cochrane Library up to January 2021. The review included systematic reviews and meta-analyses as well as clinical trials not included in those studies and high-quality real-world studies. National and international clinical practice guidelines and consensus documents on the management of moderate to severe psoriasis were also reviewed. The coordinator then drew up a set of proposed recommendations, which were discussed and modified in a nominal group meeting. After several review processes, including external review by other GPs members, the final document was drafted.

ResultsThe present guidelines include updated recommendations on assessing the severity of psoriasis and criteria for the indication of systemic treatment. They also include general principles for the treatment of patients with moderate to severe psoriasis and define treatment goals for these patients as well as criteria for the indication and selection of initial and subsequent therapies Practical issues, such as treatment failure and maintenance of response, are also addressed.

El desarrollo del actual arsenal terapéutico fundamentado en las terapias biológicas, la experiencia acumulada en ensayos clínicos y en práctica clínica real y los nuevos conocimientos sobre la patogénesis en psoriasis permiten posibilidades de individualización y hacen adecuada una actualización de las recomendaciones en cuanto a la gestión del riesgo en pacientes tratados con estos fármacos.

El Grupo de Psoriasis de la Academia Española de Dermatología y Venereología (GPS) trabaja desde su creación en la actualización continua de las recomendaciones para el tratamiento de la psoriasis, basándose en la mejor evidencia disponible e incorporando propuestas orientadas desde y para la práctica clínica.

MetodologíaPara la elaboración del consenso se siguió la metodología de grupos nominales, con ayuda de una scoping review. Tras designar a un coordinador, se seleccionó un grupo de trabajo constituido por integrantes del GPS con base en su experiencia y conocimiento en psoriasis. El coordinador definió los objetivos y puntos clave del documento y con ayuda de un documentalista se realizó una scoping review incluyendo datos de Medline, Embase y Cochrane Library (hasta enero del 2021). Se seleccionaron revisiones sistemáticas, metaanálisis y ensayos clínicos no incluidos en las mismas, guías de práctica clínica y documentos de consenso nacionales e internacionales, así como estudios de calidad en vida real. El coordinador generó las recomendaciones preliminares que fueron evaluadas y modificadas en una reunión de grupo nominal. Tras varios procesos de revisión, que incluyeron la revisión externa por parte de los miembros del GPS, se redactó el documento definitivo.

ResultadosSe presentan en este documento recomendaciones prácticas y actualizadas relativas a la toma de decisiones terapéuticas con el uso de las terapias biológicas en pacientes que pertenecen a poblaciones especiales (ancianos, edad pediátrica, mujeres embarazadas o con deseo gestacional) o que presentan comorbilidades (obesidad, artritis psoriásica, enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal, depresión, cáncer, síndrome metabólico, diabetes, hígado graso no alcohólico, enfermedad cardiovascular, insuficiencia cardiaca y enfermedad renal o neurológica). Se aborda también la gestión del riesgo con el uso de terapias biológicas, analizando los riesgos potenciales previos al tratamiento y durante el mismo, así como los acontecimientos adversos más frecuentes, todo ello desde una orientación práctica y adaptada a la práctica clínica habitual.

Decisions regarding the use of biologic therapies in psoriasis are influenced not only by drug- and disease-related variables such as efficacy and severity or impact, but also by patient-related factors such as age, pregnancy plans, and comorbidities.1,2

This updated consensus statement incorporates a series of changes and additions with respect to previous publications on the management of special populations, comorbidities, and risk in the setting of moderate to severe psoriasis treated with biologic therapies.3–6

MethodsThe methodology underlying this project, an initiative of the Psoriasis Group (GPs) of the Spanish Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (AEDV), is described in Part 1 of this publication.7 In brief, consensus on the recommendations presented was reached using the nominal group technique supported by a scoping review and methodologic oversight.

The first step was to assign a group coordinator and then select a group of (GPs in its Spannish acronym) members with experience and knowledge of psoriasis to form the nominal group. The coordinator, with methodologic support, defined the objectives, scope, users, and sections of the consensus statement. Considering the volume of publications on the efficacy and safety of biologic therapies, including biosimilars and new-generation synthetic molecules, in moderate to severe psoriasis, it was decided to conduct a scoping review. This review was conducted by the group coordinator with the help of an expert documentalist, who designed several search strategies that included Medical Subject Heading and free-text terms for the main bibliographic databases: Medline, Embase, and the Cochrane Library. The search targeted articles published up to January 2021. The following studies were selected for review: systematic reviews, meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) not included in the previous 2 groups, and high-quality real-world studies. National and international clinical practice guidelines and consensus statements on the management of moderate to severe psoriasis were also reviewed.

Based on the results of the scoping review, the group coordinator drew up a series of preliminary recommendations and drafted the sections of the consensus statement, which were evaluated, discussed, and modified in a nominal group meeting. After several rounds of revision, which included external review by GPs members, the definitive statement was drawn up.

The project was conducted in accordance with the principles of the latest version of the Declaration of Helsinki on medical research involving human subjects and applicable regulatory requirements on good clinical practice.

ResultsTreatment decisions in special populations.

Patients Older Than 65 YearsCumulative experience with the use of biologic therapies in psoriasis patients aged over 65 years is limited. These patients are poorly represented in RCTs because, apart from age restrictions, they typically have a higher burden of comorbidities and/or do not meet certain requirements.

A recent systematic review summarized the results of 18 studies (3 RCT subanalyses, 5 cohort studies, and 10 case series) on the use of biologic therapies in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis older than 65 years.8 Overall, biologics had a similar efficacy to that reported for younger patients, although some of the studies reported an increased risk of adverse events (including serious ones) in patients older than 65 years, although the risk associated with conventional systemic therapies was even higher.9,10 The main findings of the studies are summarized in Table 1.

Efficacy and Safety of Biologic Therapies in Patients Older Than 65 Years With Moderate to Severe Psoriasis.

| Drug | Study design | No. | Efficacy | Safety |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IFX11 | Case series | 27 | -Wk 12PASI 75: 80%Mean PASI reduction (P<.001) | -15 discontinuations (5 due to AEs) |

| ETN12 | RCT subanalysis | 77 | -PASI 75: no differences with younger patients | -No differences in discontinuation or injection reaction rates compared with younger patients-Significantly more serious AEs (unrelated to ETN) in older patients |

| ADA13 | Retrospective | 16 | -No differences with young patients | -No differences-Discontinuations unrelated to age; OR=0.94 (95% CI, 0.29–3.07) |

| ADA14 | RCT subanalysis | 54 | -PASI 75≥ 65 y: < 61%40–64 y: 70%< 40 y: 74% | – |

| ETN, ADA15 | Case series | 89 | -Wk 156PASI 75: ETN 83.6%PASI 75: ADA 71.4%No differences in mean PASI reduction (P<.001) compared with younger patients except for ETN | -26 discontinued due to AEs |

| SEC16 | RCT subanalysis | 67 | -Wk 16 (> 65 y vs. younger patients)PASI 75: 86.4% vs. 89%PASI 90: 72.7% vs. 74.3%PASI 100: 40.9% vs. 40.9%-Wk 52 (> 65 y vs. younger patients)PASI 75: 81.1% vs.79.4%-Similar time to response | - > 65 y vs. younger patients:AEs: 14.9% vs. 8.2%Serious SEC-related AEs: 4.5% vs. 1.8%Discontinuation rate due to AEs: 7.5% vs. 1.8%Similar infection rate |

| UST17 | Case series | 22 | -Wks 28/52/100PASI 75: 63.6%/86.4%/90.9% | -0 serious AEs-2 serious AEs |

| UST18 | Case series | 24 | -Wks 16/28/52PASI 75: 56.5%/59.1%/60% | -0 serious AEs-2 discontinued |

| GUS | Case series | 20 | -Wks 4/28/40–44PASI 90: 30%/65%/75%PASI 100: 10%/30%/55% | -2 discontinued |

| BRO19 | RCT subanalysis | 224 | -Wk 52PASI 75: 94.6%PASI 100: 52.7%-Wk 120PASI 75: 91.4%PASI 100: 56.9% | -AEs per 100 patient-years: 308.2-Serious AEs per 100 patient-years: 13.1 |

| ADA, UST20 | Case series | 27 | -Wks 16/24/52PASI 75: 76.9%/88%/90.5% | -7 discontinuations |

| TIL, ETN21 | RCT subanalysis | 161 | – | -Incidence TIL 100mg/TIL 200mg/ETNSerious AEs: 2.51/1.76/6.83Serious infections: 3.76/2.34/6.83 |

| RIS22,23 | RCT subanalysis | 64 | -Wks 16/52PASI 90: –/81.3%PASI 100: 42.2%/60.9% | – |

| Various drugsa,24 | Case series | 266 | -Mean change in PASI:Wk 0: 16.5Wk 16: 3.7Wk 28: 1.6Wk 52: 1.2 | -Twenty-five AEs (9.4%) (infections more common)Four cancers (3 nonmelanoma skin cancers)-Discontinuation rates:Wk 16: 3%Wk 28: 5%Wk 52: 9% |

| Various drugsb,25 | Retrospective | 48 | -Older vs. younger patients: more topical and fewer biologic treatments-Older patients tended to have better results with biologics than with conventional systemic treatments-No differences in improvement in S-MAPA at wk 12 compared with younger patients | -No differences in AE or infection rates with biologics compared with younger patients-Higher percentage of AEs with classic synthetic molecules compared with biologics in older patients-IFX associated with most infections and ETN with fewest in all age groups |

| Various drugsc,26 | Case series | 187 | -Wk 12: PASI 75PASI 75: ETN 64%PASI 75: ADA 65%PASI 75: IFX 93%PASI 75: UST 100% | -AEs 0.11, 0.35, 0.19, and 0.26 per patient-years with ETN, ADA, IFX, and UST-More AEs with ADA than with ETN (P<.050)-Two serious AEs (pneumonia with IFX and ETN) |

| Various drugsd,27 | Retrospective | 65 | -Older patients treated with fewer biologics than younger patients, but percentage rose from 7.75% in 2008 to 11.7% in 2012 | -Discontinuation rate (>65 y vs. younger patients) 18.2% vs. 12%-Total AEs in patients>65 y; HR=1.09 (95% CI, 0.9–1.3)-Serious AEs in patients >65 y; HR=3.2 (95% CI, 2.0–5.1) |

| Various drugse,28 | Retrospective | 31 | -29.8% of patients on systemic treatment would not be eligible for inclusion in RCTs | -Serious AEs in patients ≥70 y; HR=3.4 (95% CI, 1.6–7.1) |

Abbreviations: ADA, adalimumab; AEs, adverse events; BRO, brodalumab; CER, certolizumab pegol; EFA, efalizumab; ETN, etanercept; GOL, golimumab; GUS, guselkumab; HR, hazard ratio; OR, odds ratio; PASI, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index; PASI 75/90/100, 75%/90%/100% reduction in mean PASI; RCT, randomized controlled trial; S-MAPA, Simple-Measure for Assessing Psoriasis Activity; SEC, secukinumab; TIL, tildrakizumab; UST, ustekinumab.

The GPs considers that treatment goals for patients older than 65 years should be the same as those recommended for the general population (see Part 1 of the GPs consensus statement). The same applies to choice and use of biologic therapies, although special attention needs to be paid to risk management.

Pediatric PatientsEtanercept, adalimumab, ustekinumab, ixekizumab, and secukinumab are currently licensed for use in pediatric patients with psoriasis (see Table 2).29–33 The treatment goals in this setting should be identical to those established for adults. Accordingly, children should have immediate access to biologic therapies, particularly considering that conventional treatments are not approved for use in this population. Convenience issues, such as frequency and number of injections and associated pain, are important as they can influence treatment adherence.

SPC Indications and Main Results From RCTs of Biologic Drugs Approved for Psoriasis in Pediatric Patients.

| Drug | SPC indications | RCT results |

|---|---|---|

| Etanercept29 | -Treatment of chronic severe plaque psoriasis in children and adolescents from the age of 6 years who are inadequately controlled by, or are intolerant to, other systemic therapies or phototherapies | -Wk 12: etanercept vs. placeboPASI 75: 57% vs. 11% (P<.001)PASI 90: 27% vs.7% (P<.001)PGA 0/1: 53% vs. 13% (P<.001)-Wk 36 etanerceptPASI 75: 65%-68% |

| Adalimumab30 | -Treatment of severe chronic plaque psoriasis in children and adolescents from the age of 4y who have had an inadequate response to or are inappropriate candidates for topical therapy and phototherapies | -Wk 16 adalimumab vs. methotrexatePASI 75: 58%–44% vs. 32%PhGA 0/1: 61%–41% vs. 41%-Wk 36 adalimumabAdequate response in all cases |

| Ustekinumab31 | -Treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis in children and adolescents from the age of 12y who are inadequately controlled by, or are intolerant to, other systemic therapies and phototherapies | -Wk 12 ustekinumab (dose-dependent) vs. placeboPASI 75: 80.6%–78.4% vs. 10.8% (P<.001)PASI 90: 61.1%–54.1% vs. 5.4% (P<.001)PhGA 0/1: 69.4%–67.6% vs. 5.4% (P<.001)-Wk 52 ustekinumabMaintenance of PASI responses |

| Ixekizumab32 | -Treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis in children from the age of 6y with a body weight of at least 25kg and adolescents who are candidates for systemic therapy | -Wk 12: ixekizumab vs. placeboPASI 75: 89% vs. 25% (P<.001)PASI 90: 78% vs. 5% (P<.001)PhGA 0/1: 81% vs. 11% (P<.001)-Wk 48 ixekizumabMaintenance of PASI responses |

| Secukinumab33 | -Treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis in children and adolescents from the age of 6y who are candidates for systemic therapy | -Wk 12 secukinumab (dose-dependent) vs. placeboPASI 75: 77.5%–80% vs. 14.6% (P<.001)PASI 90: 76.5%–72.5% vs. 2.4% (P<.001)IGA mod 2011: 60%–70% vs. 4.9% (P<.001)-Wk 52 secukinumabPASI 75: 72.2%–85%PASI 90: 75%–81.3%IGA mod 2011: 72.2%–85% |

Abbreviations: IGA mod 2011, Investigator's Global Assessment modified 2011; PASI, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index; PASI 75/90/100, 75%/90%/100% reduction in mean PASI; PGA; Physician Global Assessment; PGhA, Physician Global Assessment of patient's health status; RCTs, randomized controlled trial; SPC, summary of product characteristics.

A recent phase III RCT reported good outcomes for secukinumab up to week 5233 and the drug is licensed for use in patients older than 6 years. Guselkumab, brodalumab, tildrakizumab, certolizumab pegol, bimekizumab, and risankizumab are currently being investigated in pediatric patients. Inflixmab34–36 and guselkumab37 have also been studied in case series and open-label studies involving this population.

In 2020, the GPs published a consensus statement on the management of psoriasis during preconception, pregnancy, postpartum, and breastfeeding.2Tables 3 and 4 summarize the recommended uses of biologic therapies according to the respective summaries of product characteristics (SPCs) and also provide pregnancy- and breastfeeding-related data.

SPC Recommendations on the Use of Biologic Treatments (Including Biosimilars and New-generation Synthetic Molecules) During Pregnancy.

| Drug | SPC recommendation | Other published data |

|---|---|---|

| Infliximab49,58 | Use if benefit outweighs risk | No data showing association with teratogenicity or poor pregnancy outcomes. No evidence of harm in animals. |

| Adalimumab49,59 | Use if benefit outweighs risk | No data showing association with teratogenicity or poor pregnancy outcomes. No evidence of harm in animals. |

| Etanercept50 | Use if benefit outweighs risk | No data showing association with teratogenicity or poor pregnancy outcomes. No evidence of harm in animals. |

| Certolizumab pegol46,47,59,60 | Use during pregnancy if clinically necessary | Results similar to in the general population. |

| Brodalumab59 | Preferable to avoid use | Lack of data in humans. No evidence of harm in animals. |

| Ixekizumab59,61 | Preferable to avoid use | Lack of data in humans. Animal studies indicate possibility of neonatal death. |

| Secukinumab53 | Preferable to avoid use | No data showing association with teratogenicity or poor pregnancy outcomes. No evidence of harm in animals. |

| Bimekizumab | Preferable to avoid use | No data showing association with teratogenicity or poor pregnancy outcomes. No evidence of harm in animals. |

| Guselkumab62,63 | Preferable to avoid use | Lack of data in humans. |

| Risankizumab6 | Preferable to avoid use | Lack of data in humans. Animal studies do not indicate direct or indirect harmful effects with respect to reproductive toxicity. |

| Ustekinumab41,54–56 | Preferable to avoid use | Lack of data in humans. |

| Tildrakizumab57 | Preferable to avoid use | Lack of data in humans. |

SPC Recommendations on the Use of Biologic Treatments (Including Biosimilars and New-generation Synthetic Molecules) During Breastfeeding.

| Drug | Breastfeeding |

|---|---|

| Infliximab58 | -Not generally detected or detected at low doses in breast milk-AEMPS: As human immunoglobulins are excreted in milk, women should not breastfeed for at least 6 months after treatment |

| Adalimumab59,64 | -Not generally detected or detected at very low doses in breast milk; concentrations corresponding to 0.01%–1.0% of maternal serum levels detected in human milk-AEMPS: Can be used during breastfeeding |

| Etanercept65 | -Not generally detected or detected at low doses in breast milk-AEMPS: Decide whether to interrupt breastfeeding or interrupt treatment with etanercept after considering the benefits of breastfeeding for the child and of treatment for the mother |

| Certolizumab pegol66 | -Not generally detected or detected at low doses in breast milk-Approved by the EMA for use in breastfeeding |

| Brodalumab59 | -Transfer to breast milk unknown-AEMPS: Decide whether to interrupt breastfeeding or to interrupt/not start treatment with brodalumab after considering the benefits of breastfeeding for the child and of treatment for the mother |

| Ixekizumab59 | -No data on humans-AEMPS: Decide whether to interrupt breastfeeding or to interrupt treatment with ixekizumab after considering the benefits of breastfeeding for the child and of treatment for the mother |

| Secukinumab59 | -Not generally detected or detected at low doses in breast milk-AEMPS: Decide whether to interrupt breastfeeding during and up to 20 weeks after treatment with secukinumab or to interrupt treatment with secukinumab after considering the benefits of breastfeeding for the child and of treatment for the mother |

| Bimekizumab67 | -Transfer to breast milk unknown-AEMPS: Decide whether to interrupt breastfeeding or to interrupt/not start treatment with bimekizumab after considering the benefits of breastfeeding for the child and of treatment for the mother |

| Guselkumab62,63 | -No data on humans-AEMPS: Decide whether to interrupt breastfeeding during treatment and up to 12 weeks after the last dose of guselkumab or to interrupt guselkumab after considering the benefits of breastfeeding for the child and of treatment for the mother |

| Risankizumab6 | -Transfer to breast milk unknown-AEMPS: Decide whether to interrupt breastfeeding or to interrupt/not start treatment with risankizumab after considering the benefits of breastfeeding for the child and of treatment for the mother |

| Ustekinumab41,56 | -No data on humans-AEMPS: Decide whether to interrupt breastfeeding during and up to 15 weeks after treatment with ustekinumab or to interrupt ustekinumab after considering the benefits of breastfeeding for the child and of treatment for the mother |

| Tildrakizumab68 | -Transfer to breast milk unknown-Negligible levels of tildrakizumab have been observed in cynomolgus monkey milk on postnatal day 28-AEMPS: Decide whether to interrupt breastfeeding or to interrupt/not start treatment with tildrakizumab after considering the benefits of breastfeeding for the child and of treatment for the mother |

Abbreviations: AEMPS, Spanish Agency for Medicines and Medical Devices; EMA, European Medicines Agency.

Placental passage of immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies from mother to child occurs from the third trimester onwards via binding of the Fc region to the neonatal Fc receptor for IgG (FcRn) in the placenta.38 Monoclonal antibodies, however, differ in how they are transferred across the placenta as they have different affinities for FcRn. IgG1 (adalimumab, infliximab, secukinumab, ustekinumab, guselkumab, tildrakizumab, and risankizumab), IgG2 (brodalumab), and IgG4 (ixekizumab) probably cross in a similar fashion.39–42 Infliximab and adalimumab have been detected in the blood of newborns up to 6 months after birth.43 Etanercept has also been reported to have lower affinity for FcRn.44,45 Little or no transplacental transfer has been described for certolizumab pegol, which lacks an Fc region.46–48

Cumulative experience with the use of TNF inhibitors does not show an increased risk of teratogenesis or a negative impact on prognosis in pregnancy (including maternal infections).49,50 Prospective studies of certolizumab pegol in more than 1300 pregnant women did not find an increased risk of fetal malformations or death.51,52 Based on these findings, the European Medicines Agency approved the continued use of certolizumab pegol during pregnancy and breastfeeding when deemed clinically necessary.

The GPs recommends considering maintaining biologic therapy during the first and second trimesters of pregnancy and weighing up risks and benefits during the third trimester. Certolizumab pegol can be maintained throughout pregnancy when considered clinically necessary.

Alternatives to brodalumab, ixekizumab, secukinumab,53 guselkumab, risankizumab, ustekinumab,41,54–56 bimekizumab, and tildrakizumab57 in pregnant women should be sought given the scarcity of data available. If no alternatives are possible or if it considered that one of these drugs should be maintained or is more appropriate in a given situation, the matter should be discussed and decided on with the patient following careful assessment of the risk-benefit ratio.

Decisions regarding the use of biologic therapy should take patients’ wishes to become pregnant into account. Ideally, women with moderate to severe psoriasis should plan to become pregnant when they are in remission and not on medication or when they are taking the lowest effective dose of a drug with a good safety profile in pregnancy.

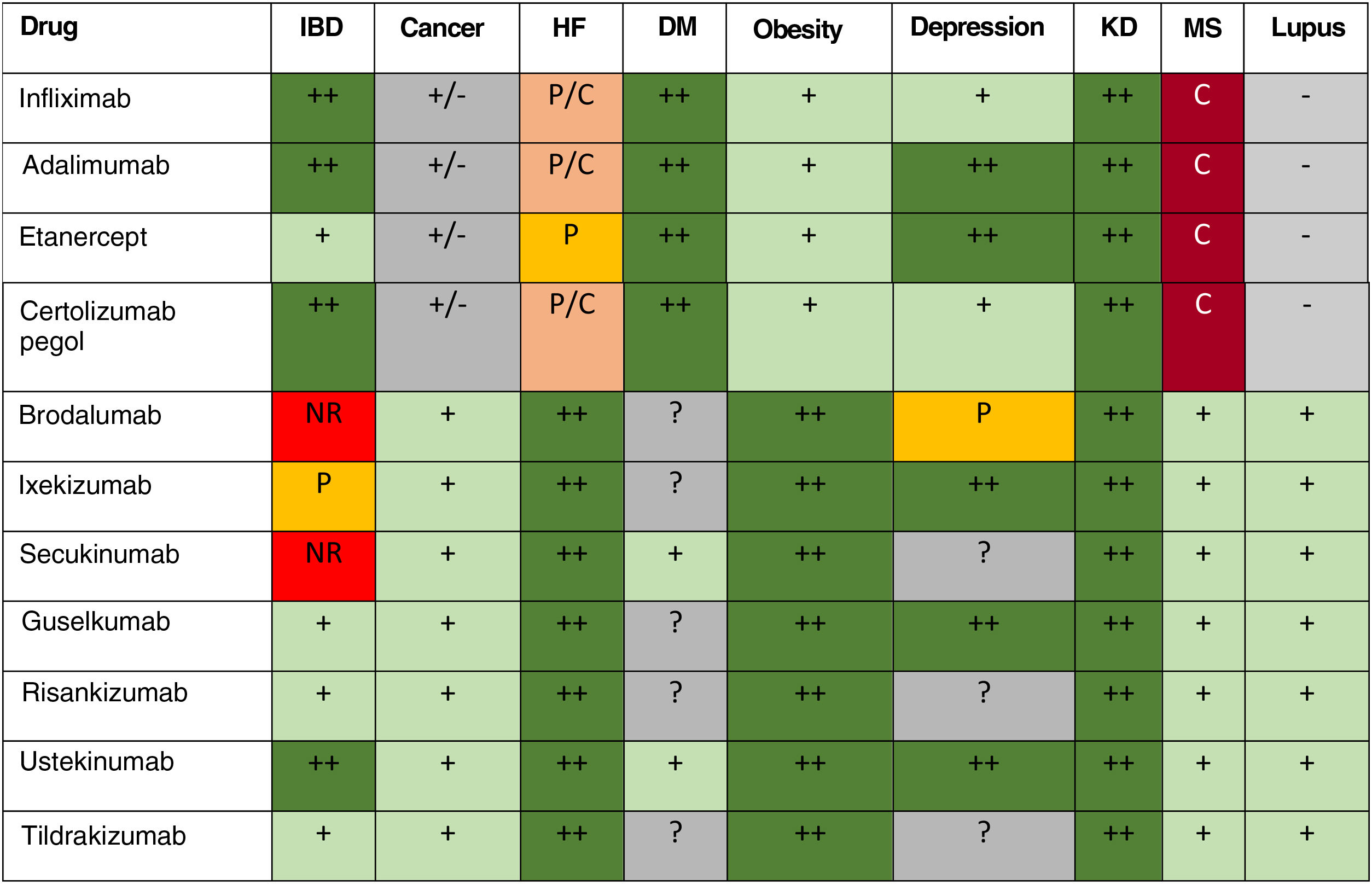

Treatment Decisions in Patients With ComorbiditiesThe GPs considers it important to note that the presence of certain comorbidities can influence or determine choice of biologic treatment due to safety issues or potential class effects. The main findings and recommendations in this respect are summarized in Table 5.

Summary of Impact of Main Comorbidities on the Use of Biologic Therapies and Practical GPs and SPC Recommendations.

| Comorbidity | Study results | Practical recommendations |

|---|---|---|

| Obesity14,69–76 | -Reduced efficacy with increasing body weight (especially in obese patients) | -Refer to primary care or other specialist for weight control |

| PsA77–80 | -Variable efficacy depending on drug and domain (arthritis, enthesitis, axial joint disease, dactylitis, etc.) | -Evaluate involvement of each PsA domain-Agree on treatment strategy with rheumatologist |

| IBD81–86 | -New-onset IBD is very uncommon with IL-17 inhibitors-RCTs with secukinumab and brodalumab in IBD were discontinued due to a lack of efficacy or worsening of disease | -Prioritize treatments other than IL-17 inhibitors-Agree on treatment strategy with gastroenterologist-Exert special caution in patients with a family history of IBD or spondyloarthritis or digestive symptoms that may be compatible with IBD |

| Depression5,87–90 | -Depression is very common in psoriasis, especially in patients with severe disease-Some RCTs of brodalumab detected some cases of suicide in patients with a history of psychiatric disease | -Routinely assess psychological and psychiatric comorbidities and request specialized evaluation if underlying disorder detected-Weigh up risks and benefits of brodalumab in patients with a history of depression or suicidal ideation |

| Cancer91–97 | -No evidence that the use of biologic therapies is associated with de novo or recurrent cancer | -Agree on treatment strategy with patient and oncologist |

| Metabolic syndrome1 | -Very common, especially in patients with severe psoriasis-No evidence that it is affected by biologic therapies | -No specific actions required other than management by primary care or an appropriate specialist |

| Diabetes98–103 | -Discordant results for TNF inhibitors-Inconclusive data for other biologics | -Assess whether or not to prioritize ustekinumab or IL-17 or IL-23 inhibitors in patients with advanced diabetes |

| Nonalcoholic fatty liver102,104–108 | -Very common-TNF inhibitors have been shown to improve metabolic and liver parameters-Animal studies have shown beneficial effects for IL-17 inhibitors | -No specific actions necessary at this time |

| Cardiovascular disease and risk109 | -Potential beneficial effects with biologic therapies | -No specific actions necessary at this time |

| Heart failure110,111 | -Worsening of heart failure with TNF inhibitors, especially adalimumab and infliximab and especially in advanced stages (III/IV)-No signs of risk with other biologic therapies | -TNF inhibitors are contraindicated in patients with stage III/IV heart failure and should be used with caution in those with stage I/II disease |

| Kidney disease112–115 | -No evidence that biologic therapies have a negative impact on kidney disease | -No specific actions currently necessary |

| Neurologic disease116–118. | -(Low) risk of new-onset or worsening of demyelinating disease with TNF inhibitors-No evidence of risk with other biologic therapies | -TNF inhibitors are contraindicated in patients with demyelinating disease |

Abbreviations: IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; IL, interleukin; PsA, psoriatic arthritis; RCT, randomized controlled trial; SPC, summary of product characteristics; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

Overweight and obesity can reduce treatment efficacy in psoriasis. Body weight can affect the efficacy of all biologic drugs to a greater or lesser extent, and this in turn can influence the achievement of optimal treatment goals.14,69,71–75,119

A number of studies have shown that higher body weight, and obesity in particular, can reduce the efficacy of TNF inhibitors.14,69–71 A similar, though lesser, effect has been reported for other biologics.72,73 One study of ustekinumab showed that body weight, female sex, and diabetes affect drug clearance and volume of distribution.74 A phase II RCT examining the safety and efficacy of secukinumab showed numerically higher responses in normal-weight patients compared with obese patients, although the drug was efficacious in both cases75; similar findings were reported for brodalumab in 2 phase III RCTs.75,120 Treatment with ixekizumab was associated with numerically lower Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) responses (PASI 75, 90, and 100) in higher body weight categories.76 According to the SPC for bimekizumab, administration of 320mg every 4 weeks after week 16 could continue to improve treatment response in patients weighing at least 120kg who have not achieved full skin clearance. Pooled data from 2 phase III RCTs of guselkumab showed lower numerical efficacy in patients with a higher body weight.72 Similar findings were described for risankizumab (pooled data from 2 phase III RCTs)22 and tildrakizumab (pooled data from 1 phase IIb RCT and 2 phase III RCTs).73 Infliximab and ustekinumab doses can be adjusted to body weight. In the latter case, a 90-mg dose is recommended as ustekinumab 45mg has shown suboptimal efficacy in patients weighing 90 to 100kg.121

According to their respective SPCs, TNF inhibitors may lead to weight gain. The implications of this, however, should be evaluated on a case-by-case basis.

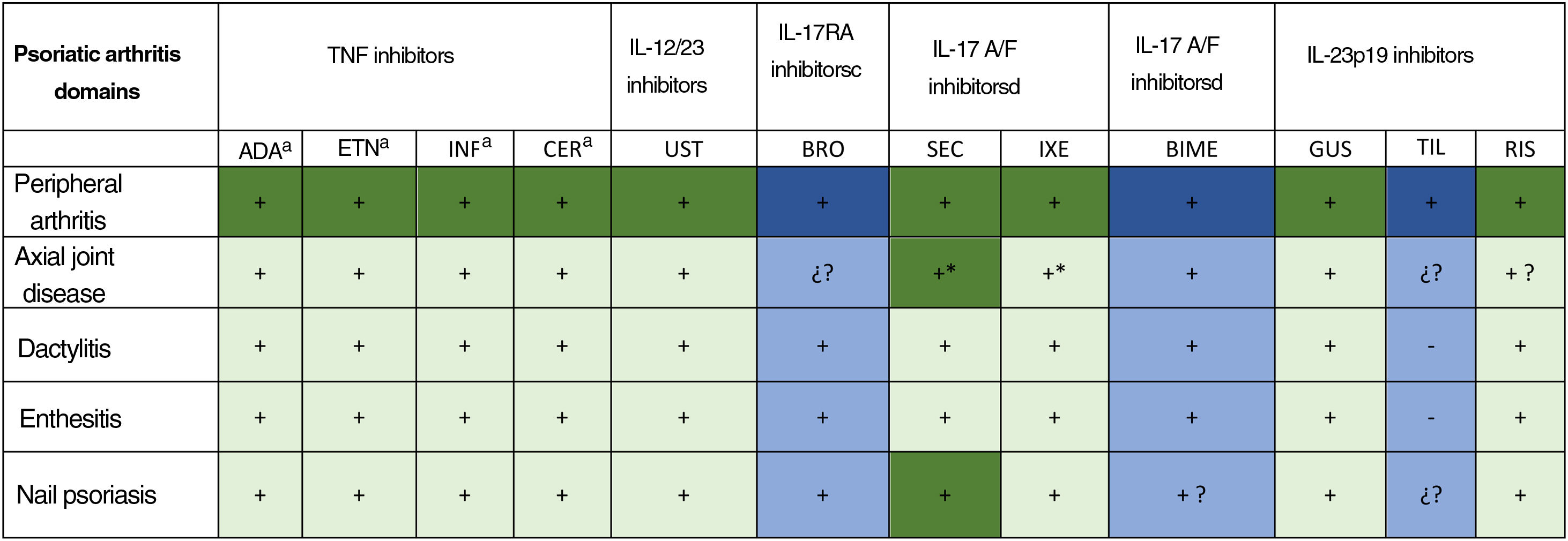

Psoriatic ArthritisInvolvement of each of the clinical domains of psoriatic arthritis (PsA) (peripheral joint disease, axial joint disease, enthesitis, dactylitis, nail psoriasis, and skin psoriasis) should be assessed in patients with concomitant psoriasis and PsA. Treatment decisions should be made in conjunction with a rheumatologist according to the severity and impact of disease in each domain.77,122 Several psoriasis drugs are also licensed for use in PsA: TNF inhibitors (adalimumab, infliximab, etanercept, certolizumab), interleukin (IL) 17 inhibitors (secukinumab, ixekizumab), anti-p40 monoclonal antibodies (ustekinumab), and IL-23 inhibitors (guselkumab, risankizumab).

Bimekizumab is a dual IL-17A and IL-17F inhibitor. In phase IIb RCTs, bimekizumab doses of 16mg and 160mg (with or without a 320-mg loading dose) had an acceptable safety profile and were associated with significant improvements in ACR50 responses (≥50% improvement according to American College of Rheumatology criteria) compared with placebo.123

In phase IIb trials, tildrakizumab was associated with significant improvements in joint manifestations of PsA compared with placebo.124 Brodalumab, an IL-17RA inhibitor, was investigated in phase III trials, but these were discontinued.

At the time of writing, phase III trials examining the use of bimekizumab and tildrakizumab in the treatment of PsA are underway.

The efficacy results for different biologic drugs (including biosimilars and new-generation synthetic molecules) from phase III RCTs are summarized in Fig. 1.80,122

Efficacy of biologic drugs (including biosimilars and new-generation synthetic molecules) in psoriatic arthritis according to phase III randomized controlled trials.80 TNF indicates tumor necrosis factors; IL, interleukin; ADA, adalimumab; ETN, etanercept; IFX, infliximab; CER, certolizumab pegol; UST, ustekinumab; BRO, brodalumab; SEC, secukinumab; IXE, ixekizumab; BIME, bimekizumab; GUS, guselkumab; IL, interleukin; PsA, psoriatic arthritis; RIS, risankizumab; TIL, tildrakizumab.

Colors. Dark green means that the domain was the primary endpoint of a completed phase III trial designed to assess that domain; light green, that the domain was the secondary endpoint in a completed phase III trial; dark blue, that the domain is the primary endpoint in an ongoing phase III trial with phase II results available; and light blue, that the domain is a secondary endpoint in an ongoing phase III trial with phase II results available.

+ efficacious; − not efficacious; +? few data or data not published in indexed journals;?? No data available.

a Approved for axial spondyloarthritis (ankylosing spondylitis/nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis).125

b Not approved for psoriatic arthritis; phase III RCT discontinued by sponsor.

c Not approved for psoriatic arthritis; phase III RCT underway.

Several meta-analyses have shown that all the biologics licensed for use in PsA are superior to placebo and do not differ significantly from each other in this setting. Overall findings from some of the studies indicate that ustekinumab may be superior to the other approved biologics.126,127

Nevertheless, other factors need to be taken into account, such as differences in evaluation times, a generally faster response to TNF and IL-17 inhibitors among patients with joint disease, and additional issues that affect prescribing decisions, such as pharmacoeconomics, impact on psoriasis, and history of previous biologic failures.128

Meta-analyses have shown that all the biologics used in PsA are similarly effective against dactylitis and enthesitis.129,130

Biologic agents may delay radiographic progression of bone erosion and joint space narrowing in patients with PsA compared with placebo. Methotrexate seems to have no added effect. Previous TNF inhibitor therapy does not appear to influence the efficacy of IL inhibitors in delaying radiographic progression.131

Inflammatory Bowel DiseasePatients with psoriasis have an increased incidence of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), whether Crohn disease or ulcerative colitis.81 IBD, therefore, may be an important factor to consider when choosing a biologic. The impact of a family history of IBD in this setting is not well established.

Certolizumab pegol is licensed for use in Crohn disease, while infliximab, adalimumab, and ustekinumab can be used in both Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis; these biologics could thus be prioritized in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis and IBD.82

Although guselkumab and risankizumab are not approved for the treatment of IBD, evidence from phase II/III RCTs suggests that they are efficacious in this setting. They may, therefore, be an acceptable option if considered appropriate for the treatment of psoriasis. Guselkumab and risankizumab have shown good results as induction and maintenance therapies in Crohn disease.83 Experience with tildrakizumab in this setting is limited to expert opinions.132

New-onset IBD during IL-17 inhibitor therapy is uncommon and the incidence is no higher than would be expected in psoriasis.86 Some cases of new-onset IBD have been described in association with IL-17 inhibitors, and RCTs investigating the use of secukinumab and brodalumab in IBD were discontinued due to a lack of treatment response and, in some cases, a worsening of disease.6,84,85 The GPs recommends deciding on a treatment strategy in conjunction with a gastroenterologist.

DepressionMental health comorbidities, such as anxiety, depression, or suicidal ideation and behavior are common in psoriasis, particularly in patients with more severe disease. The association between psychological and psychiatric disorders and psoriasis is bidirectional, and there may be shared pathogenic mechanisms.87

Adalimumab, etanercept, ustekinumab, ixekizumab, and guselkumab have been shown to improve depressive symptoms associated with psoriasis in RCT settings. A number of suicides were reported in 2 of the 3 phase III RCTs of brodalumab. They involved patients with a history of psychiatric disorders or stress triggers, and no causal relationship was found between the use of brodalumab and an increased risk of suicidal ideation or behavior. The other patients with psychiatric symptoms experienced an improvement during treatment.88 Nonetheless, the SPC indicates that it is necessary to weigh up the risks and benefits of using brodalumab in patients with a history of depression or suicidal ideation. Brodalumab should be discontinued on appearance or worsening of depressive symptoms or suicidal ideation.89

The GPs recommends routinely evaluating psychiatric comorbidities in patients on treatment with biologics for moderate to severe psoriasis and referring them for follow-up and specialized assessment when an underlying disorder is detected.5

Considering the complexity of the psychosocial factors associated with psoriasis, dermatologists and health professionals should help their patients develop coping strategies to manage the effects of their disease on physical, psychological, and social well-being.5,90

CancerPatients with psoriasis and PsA have a slightly increased risk of certain types of cancer, mostly nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC) and lymphoma.91

Most evidence on the use of biologic therapies in patients with psoriasis and a previous history of cancer is based on registry or case series data or theories related to the drugs’ mechanisms of action. The purported association between the immune-modulating effects of biologics and an increased risk of cancer has also been questioned, as robust evidence is lacking. In addition, general recommendations on the use of biologics in patients with psoriasis and a past history of cancer cannot be made due to the sheer number of factors at play, such as type of cancer, time since diagnosis or remission (which is linked to recurrence risk), and patient-related factors such as age and smoking history. Finally, there is no evidence to date that TNF inhibitors increase the risk of cancer recurrence in other chronic inflammatory diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis and IBD, except in patients receiving combination immunosuppression therapy.92,93

The risk of de novo cancer in patients treated with biologics has been studied in numerous publications and is not free of controversy. Although an increased risk of NMSC associated with TNF inhibitors has been described in systematic reviews and observational studies, there are probably confounding factors at play, such as exposure to UV radiation or high-dose psoralen plus UV therapy.95 Most of the studies conducted to date have not found an association with exposure to TNF inhibitors and an increased risk of incident cancer in patients with psoriasis.97

A systematic review of 71 RCTs involving 23458 patients with psoriasis, PsA, and other inflammatory disorders treated with adalimumab did not find a significant increase in the incidence of any type of cancer (0.96 cases per 100 patient-years; 95% CI, 0.65–1.36) or lymphoma (0.63; 95% CI, 0.01–3.49).94 The authors did, however, observe an increased incidence of NMSC (1.76; 95% CI, 1.26–2.39).

A meta-analysis of 20 RCTs analyzing the use of TNF inhibitors in 6810 psoriasis patients did not find a significant increase in the short-term incidence of cancer for any of the drugs in this class.96

Ustekinumab also does not appear to be associated with an increased risk of cancer. A subanalysis of a phase II RCT and 3 phase III RCTs found that cancer rates in patients treated with ustekinumab were similar to those observed in the general US population. Pooled data from 2 phase II RCTs involving 3117 patients with psoriasis treated with ustekinumab for up to 3 years showed a favorable safety profile.133 The overall incidence rate for cancer, excluding NMSC, was 0.98 cases per 100 patient-years (95% CI, 0.74–1.29). Specific rates were 1.42 cases per 100 patient-years (95% CI, 0.52–3.09) for melanoma, 1.21 cases per 100 patient-years (95% CI, 0.66–2.04) for prostate cancer, 0.99 cases per 100 patient-years (95% CI, 0.32–2.31) for colorectal cancer, 0.62 cases of per 100 patient-years (95% CI, 0.17–1.58) for breast cancer, and 0.80 cases per 100 patient-years (95% CI, 0.10–2.91) for lymphoma. These figures are comparable to those observed for other biologics used to treat moderate to severe psoriasis.134

Pooled results from 2 phase III RCTs and more than 1500 psoriasis patients treated with tildrakizumab showed an incidence rate of 0.6–0.7 cases of any cancer except NMSC per 100 patient-years at 5 years (dose-dependent rates). The corresponding rate for melanoma was 0.1 cases per 100 patient-years (95% CI, 0–0.3).135

Data from a phase III RCT of guselkumab showed a 5-year incidence rate of 0.34 cases of NMSC per 100 patient-years and 0.45 cases of other cancers per 100 patient-years.136

Very little information is available for the other treatments.

The EuroGuiDerm Guideline on the systemic treatment of psoriasis vulgaris suggests that both TNF inhibitors such as ustekinumab and IL-17 and IL-23 inhibitors can be used to treat moderate to severe psoriasis in patients with a previous history of cancer (taking into account time in remission). It is important to note that this recommendation is supported by a low level of evidence and that decisions should always be taken on a case-by-case basis.137

In line with the EuroGuiDerm Guideline recommendation, the GPs considers that a cancer in clinical remission, or even an active cancer, does not necessarily contraindicate the use of biologic therapy. Nonetheless, in the absence of strong evidence to the contrary, decisions must be taken in conjunction with the patient's oncologist and always discussed with the patient. The decision to use a biologic agent should be taken on a case-by case basis, with consideration of the patient's informed wishes, potential effects on quality of life, and alternatives available.

Metabolic SyndromeMetabolic comorbidities, which include obesity, diabetes, dyslipidemia, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), are common in psoriasis, particularly in severe forms of the disease. The association is linked to a common pathogenetic mechanism (the role of inflammation in the development of peripheral insulin resistance) and the frequent presence of unhealthy habits in patients with psoriasis.1

The SPCs for TNF inhibitors mention the possibility of weight gain in certain cases. Nonetheless, the potential effects of prescribing these drugs to patients with metabolic comorbidities must be evaluated on a case-by-case basis. A priori, metabolic syndrome is not a contraindication for TNF inhibitor therapy in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis.

Based on the current evidence, the GPs does not consider that the presence of metabolic syndrome should influence choice of biologic.

DiabetesDiscordant results have been published on the use of TNF inhibitors in patients with glucose metabolism and insulin sensitivity. Etanercept may improve plasma glucose levels and insulin resistance,98 and psoriasis patients on TNF inhibitor therapy have a lower risk of new-onset type 2 diabetes compared with those receiving nonbiologic treatments.99 No significant effects were found for etanercept on insulin secretion or sensitivity after 2 weeks’ treatment in a double-blind RCT involving 12 psoriasis patients with a high risk of type 2 diabetes.100 The authors of another study found no significant changes in fasting glucose levels or insulin sensitivity in 9 patients with psoriasis after 12 weeks of treatment with adalimumab.101 A pooled analysis of phase III RCTs did not find any significant effects for secukinumab on glucose metabolism.102 Nonetheless, patients with diabetes showed inferior responses to ustekinumab and secukinumab in a phase III RCT.103

In brief, based on the current evidence, the presence or absence of concomitant diabetes should not influence choice of biologic. A diagnosis of advanced diabetes, however, could justify prioritizing the use of ustekinumab or IL-17 or IL-23 inhibitors.

Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver DiseaseNAFLD is considered the leading cause of chronic liver disease in western countries and can progress from steatosis to different stages of inflammation, fibrosis, and cirrhosis (nonalcoholic steatohepatitis [NASH]). Numerous epidemiological studies have confirmed that NAFLD is approximately 50% more common in patients with psoriasis.104 Moreover, patients with psoriasis appear to be at higher risk of progressing to advanced forms of NAFLD, while patients with NAFLD have more severe forms of psoriasis.105

The pathogenic relationship between NAFLD and psoriasis is complex and probably multifactorial. Several comorbidities commonly seen in psoriasis, such as obesity, dyslipidemia, and type 2 diabetes, can also cause NAFLD, and the link appears to be a state of persistent chronic inflammation and peripheral insulin resistance.

The high prevalence of NAFLD in patients with psoriasis may influence treatment decisions. Biologics could have a favorable impact on NAFLD due to their potential effects on systemic inflammation, while TNF inhibitors have been shown to improve metabolic and liver parameters in patients with NAFLD and psoriasis.138 IL-17, in turn, was recently implicated in the pathogenesis of psoriasis and the pathogenesis and disease course of NAFLD.106

There is little or no clinical evidence on the effects of IL-17 or IL-23 on the course of NAFLD.102,107,108

Cardiovascular Disease and RiskPatients with psoriasis have an increased risk of cardiovascular events such as myocardial infarction and cerebrovascular accident. The risk increases with disease severity and is related to both the inflammatory nature of cardiovascular (CV) disease and the coexistence of components of metabolic syndrome/CV risk factors or the presence of PsA.139 Standard recommendations for patients with psoriasis include CV risk factor detection, monitoring, and prevention.1

There is no evidence that any of the biologic treatments licensed for use in psoriasis have a negative impact on CV morbidity. TNF inhibitors (adalimumab in particular) and ustekinumab may even improve CV risk factors in patients with psoriasis.137,140–142

In a systematic review of the effects of biologics on imaging and biomarkers of CV disease in patients with psoriasis, González-Cantero et al.143 did not find a significant reduction in aortic vascular inflammation in patients treated with adalimumab compared with placebo at weeks 12–16. They also found no beneficial effect for adalimumab or secukinumab compared with placebo on imaging biomarkers of CV risk (aortic vascular inflammation or flow-mediated dilatation), although they did observe a reduction in aortic vascular inflammation at week 12 (but not 52) in patients treated with ustekinumab. The main reductions in blood-based cardiometabolic risk markers were observed for adalimumab (C-reactive protein, TNF, IL-6, and GlycA) and phototherapy (C-reactive protein and IL-6) compared with placebo.143

Several observational studies using computed coronary angiography and other techniques have shown that biologic therapy has a positive effect on coronary artery plaques in patients with psoriasis, particularly those with severe forms.142,144

In a prospective observational study of patients with moderate to severe psoriasis and low CV risk according to the Framingham score, biologic treatment was associated with a 6% reduction in noncalcified coronary plaque burden (P=.005) and an additional reduction in necrotic core (P=.03) at 1 year. Patients who did not receive biologic treatment, by contrast, showed slow plaque progression (change of −0.07mm2 vs. 0.06mm2; P=.02).142 A reduction in the perivascular fat attenuation index was also observed in patients with a similar profile who had been treated with biologics; no change was observed in those not treated with biologics.142

Current evidence suggests that biologic therapies do not have a negative effect on CV comorbidity and might even have a beneficial effect, particularly in patients with low CV risk. Biologics might, therefore, improve long-term outcomes in psoriasis patients with comorbid CV disease. There is insufficient evidence, however, to support the use of biologics to treat moderate to severe psoriasis based on the concomitant presence of cardiovascular disease, or to prioritize any one treatment over the other. These considerations might change as new evidence emerges.

Congestive Heart FailureTNF inhibitors, in particular adalimumab and infliximab, are contraindicated in stage III/IV heart failure and should be used with caution in stages I and II.110 No contraindications have been established for ustekinumab or IL-17 or IL-23 inhibitors in patients with heart failure.111

Kidney DiseasePatients with psoriasis have an increased incidence of chronic kidney disease related to the higher incidence of CV and metabolic comorbidities in this setting.112 One study reported a significantly increased risk of death associated with nonhypertensive kidney disease in patients with severe psoriasis.114 Another cohort study also showed an increased risk of death due to kidney disease in psoriasis patients, even those with mild disease.113

There is no evidence that currently available biologic treatments have a negative impact on kidney function, and they might even be preferable to conventional drugs with potentially nephrotoxic effects, such as methotrexate and cyclosporin. Moreover, clearance of biologic drugs is not affected by kidney failure or dialysis.

Considering the above, the GPs does not consider kidney disease to be a contraindication for the use of biologic therapies in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis, and even believes that these treatments could be prioritized over nonbiologics in this setting.

Neurologic DiseaseA number of treatments can be used in patients with psoriasis and demyelinating diseases, such as multiple sclerosis and Guillain-Barré syndrome. The supporting evidence, however, is weak.

Based on data published so far, IL-12/IL-23 inhibitors could be used in patients with demyelinating conditions.116 There are also data supporting the use of IL-17 inhibitors in multiple sclerosis, with findings showing that secukinumab might reduce lesion activity on magnetic resonance imaging.117

New-onset and worsening of demyelinating disease have been described in psoriasis patients treated with TNF inhibitors; although demyelinating conditions are uncommon in this setting, TNF inhibitors should be avoided in patients with active demyelination.118 In some cases, the effects of demyelination may remain after treatment discontinuation. Based on the current evidence, biologics from the other therapeutic groups are not contraindicated in patients with a past history of neurologic disease.

The treatment options for psoriasis according to comorbid conditions are summarized in Table 6.

Considerations Regarding the Use of Biologic Therapies (Including Biosimilars and New-General Synthetic Molecules) According to Underlying Comorbidity.

Abbreviations: DM, diabetes mellitus; HF, heart failure; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; KD, kidney disease; MS, multiple sclerosis.

++ indicates treatment of choice; +, adequate use of treatment; +/− information with discordant or inconclusive results;?, insufficient information; C, contraindicated; NR, not recommended; P, use with precaution.

One of the main advantages of biologics in the treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis is their overall acceptable safety profile. Certain measures, however, are necessary to ensure early detection of adverse events (Table 7).

Risk Management Before and During Biologic Treatment of Moderate to Severe Psoriasis and Most Common AEs.

| Drug | Before treatment | During treatment | Most common AEs/treatment discontinuation |

|---|---|---|---|

| TNF inhibitorsInfliximabAdalimumabEtanerceptCertolizumab pegol | a) Clinical aspects-Rule out active infection (including TB), cancer, heart failure, cytopenia, demyelinating disease, relevant comorbidity-Rule out recent contact with TB patients-Discuss pregnancy plans and perform pregnancy test if necessary-Ensure measures to prevent pregnancy (except in patients on certolizumab pegol)b) Additional tests-Complete blood count, biochemistry-Serology for HVA, HVB, HVC, HIV, syphilis-Chest radiograph-Mantoux TST/IGRAsc) Other actions-Pneumococcal and flu vaccines-Consider HBV vaccination- Consider recombinant zoster vaccination-Avoid live or attenuated vaccines | a) Clinical aspects-Onset of infections (including TB), severe cytopenia, demyelinating disease, optic neuritis, cancer-Onset or worsening of heart failure and lung diseaseb) Additional tests-Complete blood count and general biochemistry 4–6 mo after treatment initiation and then at intervals tailored to the patientc) Other actions-Depending on clinical course | -Most common AEs (≥1/100 to <1/10)Infections (particularly respiratory)LeukopeniaIncreased lipidsHeadacheNausea, vomitingElevated liver enzymesInjection site reactionsMusculoskeletal pain-Consider discontinuation in following situations:Onset of cancer, demyelinating disease, optic neuritis, severe cytopenia, new or worsening interstitial lung disease, or other serious drug-related eventsOnset of infection (temporary discontinuation)Pregnancy or breastfeeding (except for certolizumab pegol) or surgery posing infection risk |

| IL-17 inhibitorsBimekizumabBrodalumabIxekizumabSecukinumab | a) Clinical aspects-Rule out active infection (including TB), cancer, cytopenia (carefully monitor neutrophil count), relevant comorbidity-Not recommended in patients with IBD-Weigh up risks and benefits in patients with a history of depression and/or suicidal behavior or ideation (see Table 6)-Rule out recent contact with TB patients-Ensure measures to prevent pregnancyb) Additional tests (similar to those used with TNF inhibitors)b) Other actions (similar to those used with TNF inhibitors) | a) Clinical aspects-Onset of infections (including TB), severe cytopenia, or other drug-related eventsb) Additional tests-Complete blood count and general biochemistry 4–6 mo after treatment initiation and then at intervals tailored to the patientc) Other actions-Depending on clinical course | -Most common AEs (≥1/100 to <1/10)Infections: candidiasis, flu, tinea, herpes simplex, athletes footHeadacheOropharyngeal painRhinorrheaGastrointestinal disorders: diarrhea and nauseaMusculoskeletal disordersGeneral disorders: fatigue, injection site reactions, including redness, pain, itching, bruising, and bleeding-Consider discontinuation in following situations:Onset of cancer, severe cytopenia, or other serious drug-related eventsOnset of infection (temporary discontinuation)Pregnancy/breastfeeding, surgery |

| IL-23 inhibitorsGuselkumabRisankizumabTildrakizumabIL-12/23 inhibitorsUstekinumab | a) Clinical aspects-Rule out active infection (including TB), cancer, cytopenia, relevant comorbiditySome patients with latent TB in the clinical trials investigating risankizumab did not receive specific TB treatment and did not experience reactivation; these findings, however, did not lead to changes in the recommendation for prophylaxis in the summary of product characteristics-Ensure measures to prevent pregnancyb) Additional tests (similar to those used with TNF inhibitors)c) Other actions (similar to those used with TNF inhibitors) | a) Clinical aspects-Onset of infections (including TB), severe cytopenia, or other drug-related eventsb) Additional tests-Complete blood count and general biochemistry 4–6 mo after treatment initiation and then at intervals tailored to the patientc) Other actions-Depending on clinical course | -Most common AEs (≥ 1/100 to < 1/10)Infections: respiratory, gastroenteritis, herpes simplex, tinea, nasopharyngitis, sinusitisHeadacheDiarrhea, nausea, and vomitingJoint pain, back pain, myalgiaOropharyngeal painPruritusFatigueInjection site redness and pain-Consider discontinuation in following situations:Onset of cancer, severe cytopenia, or other serious drug-related eventsOnset of infection (temporary discontinuation)Pregnancy/breastfeeding, surgery |

Abbreviations: AEs, adverse events; HAV, hepatitis A virus; HBV, hepatitus B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; IGRAs, interferon-gamma release assays; IL, interleukin; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; TB, tuberculosis; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; TST, tuberculin skin test.

Screening measures prior to the initiation of any biologic should be the same as those used for any systemic drug. The goal is to perform an overall evaluation of the patient's safety profile that will enable initiation of any treatment available throughout the course of disease.

Because blood tests have low sensitivity for the detection of most adverse events associated with biologic therapies, periodic testing is only recommended when deemed necessary because of treatment issues, comorbidities, or clinical status, or when indicated in the respective SPC (Table 7).

Below is a summary of risk management considerations that should be taken into account in patients receiving biologic treatment.

NeurotoxicityIn principle, TNF inhibitors are not recommended in patients with psoriasis and multiple sclerosis because they may have a pathogenic role or worsen existing symptoms. Interruption of treatment should be considered if a patient develops neurological abnormalities or experiences worsening of an existing neurological disorder.145

No cases or warnings of neurotoxicity have been described for other biologic therapies.116,117

TuberculosisStandard recommendations for biologic therapies include screening for active or latent tuberculosis (TB) before treatment initiation. Patients should undergo a targeted history to rule out a present or past history of TB, in addition to a chest radiograph and a skin and/or serologic test before treatment initiation. If latent TB is detected, prophylaxis should be started in accordance with local guidelines and recommendations. Secondary prevention of TB, however, is not free of adverse effects.

The increased risk of TB reactivation with the use of TNF inhibitors has been widely documented.146 According to a systematic review of RCTs, patients treated with IL-23 and IL-17 inhibitors did not have an increased incidence of TB compared with the general population. Clinical trials investigating the use of risankizumab in psoriasis did not detect reactivation in a number of patients with latent TB who did not receive prophylaxis.147 The SPC, however, continues to recommend TB prophylaxis in patients with latent disease.

The GPs considers that risankizumab may be an acceptable treatment for patients with latent TB when prophylaxis is contraindicated or carries a high risk. There is no experience with other drugs from the same therapeutic class (guselkumab and tildrakizumab), although they have a similar mechanism of action. Long-term real-world data on new drug classes is needed before firm recommendations can be made.

Patients with a negative TB test during screening can still develop primary TB during treatment, and general recommendations are lacking on whether and how often patients should be retested. Decisions should be taken on a case-by-case basis according to epidemiologic risk and the presence of suggestive symptoms.148 The risk of TB reactivation with different biologic drugs, including biosimilars and new-generation synthetic molecules, is summarized in Table 8.

Risk of Tuberculosis Reactivation in Patients With Moderate to Severe Psoriasis Treated With Biologic Drugs, Including Biosimilars.

| Drug(s) | Risk of tuberculosis |

|---|---|

| TNF inhibitors | Increased risk in RCT and real-world settings146,149 |

| Ustekinumab | Uncertain risk (cases described) in RCTs134,150 |

| Secukinumab | No increased risk in RCTs151,152 |

| Ixekizumab | No increased risk in RCTs149,152 |

| Brodalumab | No increased risk in RCTs149,152 |

| Guselkumab | No increased risk in RCTs149,153 |

| Tildrakizumab | No increased risk in RCTs149,154 |

| Risankizumab | No increased risk in RCTs149,155 |

Abbreviation: RCT, randomized clinical trial.

Serologic screening for hepatitis B is common practice before initiation of a biologic treatment (Table 9). The EuroGuiDerm Guideline recommends screening for both hepatitis B (hepatitis B surface antigen [HbsAg], hepatitis B surface antibody [anti-HBs], and hepatitis B core antibody [anti-HBc]) and hepatitis C before starting conventional or biologic therapy.137 Screening for hepatitis A is not recommended (strong consensus).

Interpretation of HBV Serologic Test Results.

| HBsAganti-HBcanti-HBs | NegativeNegativeNegative | Not infected or vaccinated |

| HBsAganti-HBcanti-HBs | NegativePositivePositive | Immune due to natural infection |

| HBsAganti-HBcanti-HBs | NegativeNegativePositive | Immune due to HB vaccination |

| HBsAganti-HBcanti-HBc IgManti-HBs | PositivePositivePositiveNegative | Acute HVB infection |

| HBsAganti-HBcanti-HBc IgManti-HBs | PositivePositiveNegativeNegative | Chronic HVB infection |

| HBsAganti-HBcanti-HBs | NegativePositiveNegative | Unclear interpretation with 4 possibilities:Resolved infection (most common)False-positive anti-HBc“Low-level” chronic infectionResolving acute infection |

Abbreviations: antiHBc, hepatitis B core antibody; antiHBs, hepatitis B surface antibody; HbsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen; HB, hepatitis B; HBV, hepatitis B virus.

Once immune status has been determined, administration of the first dose (or even a booster dose if deemed necessary) before initiation of biology therapy could be considered in HBsAg/anti-HBc-negative patients. The remaining doses can be administered safely, even in patients already on TNF inhibitor therapy.156,157 Patients with positive antiHBc and positive HBsAg should be considered as carriers of an active infection and should be referred to a hepatologist for evaluation before starting biologic treatment.

Anti-HBc-positive and HbsAg-negative patients are a more challenging group and should undergo hepatitis B virus DNA testing. If the result is negative, biologic therapy can be started, but the patient should be monitored according to local guidelines and in consultation with a hepatologist. Treatment should preferably be initiated with ustekinumab or an IL-17 or IL-23 inhibitor. No cases of hepatitis B reactivation have been described to date for ixekizumab, brodalumab, guselkumab, tildrakizumab, or risankizumab.158

Patients with an active infection (HbsAg-positive) must be monitored by a hepatologist and treated with an antiviral before starting psoriasis treatment with a biologic, methotrexate, or cyclosporine.

A review of the literature on the risk of hepatitis B and C virus reactivation in patients with psoriasis treated with biologics showed a very low risk of hepatitis C virus reactivation.159 There is experience with the use of etanercept, even as an adjuvant to interferon and ribavirin, in patients with psoriasis and concomitant hepatitis C infection. Compared with placebo, etanercept was associated with a higher proportion of cases without hepatitis C virus RNA and greater regression of liver fibrosis. Use of infliximab in this setting is controversial due to the risk of liver toxicity, and very little has been published on certolizumab or golimumab. Experience with ustekinumab is limited to isolated cases and the results have been controversial. Of the few patients treated with secukinumab, none of them experienced viral reactivation or worsening of transaminase levels.149

Overall, cumulative experience suggests that biologics can be used to treat psoriasis in patients with hepatitis C infection, but close coordination with the patient's hepatologist is necessary, as is clinical, laboratory, and virologic follow-up. Because hepatitis C is curable, cases will probably become considerably less common in many settings. Accordingly, the risk of its interfering with psoriasis treatment is routine practice will also become less of an issue.

HIV InfectionAlthough experience is limited, some studies have shown that combination therapy with antiretrovirals and etanercept, infliximab, adalimumab, or ustekinumab does not cause alterations and maintains good control of HIV infection. Analysis of the prospective BIOBADADERM registry found no evidence of HIV infection reactivation in psoriasis patients treated with biologic drugs in routine clinical practice.160

Although evidence is lacking, the GPs considers that patients with psoriasis and concomitant HIV infection can be treated with biologic therapy, appropriate antiviral treatment decided on in coordination with the treating infectious disease specialist, and clinical and laboratory follow-up. There is no experience with the use of anti-IL-17 or anti-IL-23 inhibitors in this setting, although no signs of an effect have been detected in studies of other chronic viral infections.

VaccinationOverall, biologics have a selective immunosuppressive mechanism that does not appear to significantly interfere with antibody production, as there have been reports of well-preserved humoral responses to vaccination.161 The main characteristics of currently available vaccines are summarized in Table 10. Table 11 summarizes the recommendations of the Advisory Committee for Immunization Practices,157 which could serve as a guide for use in routine practice.

Main Characteristics of Some of the Vaccines Available in Spain and Recommended Use During Treatment With Biologics (Including Biosimilars and Small-Molecule Drugs).

| Vaccine | Microbiologic classification | Active ingredient | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Varicella | Live attenuatedRecombinant | Attenuated varicella virus, Oka strainVaricella-zoster virus glycoprotein E | ContraindicatedPossible |

| Parotiditis, rubeola, measles | Live attenuated | Attenuated parotiditis, rubeola, and measles viruses | Contraindicated |

| Yellow fever | Live attenuated | Yellow fever virus, 17D-2004 strain | Contraindicated |

| Typhoid fever | Live attenuated | Attenuated Salmonella typhi, Ty21a strain | Contraindicated |

| Simple polysaccharides | Simple polysaccharides of Salmonella typhi, vi capsular polysaccharide | Possible | |

| Poliomyelitis | Inactivated | Inactivated polioviruses 1,2,3 | Possible |

| Influenza | Split | Split-virus influenza vaccine | Recommended |

| Subunit | Superficial hemagglutinin and neuraminidase antibodies from influenza virus | Recommended | |

| Influenza A (H1N1) | Subunit | Superficial antibodies from influenza virus | Recommended |

| Haemophilus influenza B | Conjugate | PRP-TT | Possible |

| Hepatitis A | Inactivated | Inactivated hepatitis A virus | Recommended |

| Virosome | Inactivated hepatitis A virus | Recommended | |

| Hepatitis B | Recombinant | Recombinant hepatitis B surface antigen | Recommended |

| Human papillomavirus | Recombinant | L1 proteins from human papillomavirus | Possible |

| Meningococcal C | Conjugate | De-O-acetylated polysaccharides from meningococcal C virus | Possible |

| Pneumococcal | Simple polysaccharides | 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharides | Recommended |

| Conjugate | Pneumococcal CRM197 saccharides | Recommended | |

| Conjugate | Protein D, pneumococcal polysaccharides | Recommended | |

| Diphtheria | Toxoid | Adult-type diphtheria toxoid | Possible |

| Tetanus | Toxoid | Tetanus toxoid | Possible |

| Whooping cough | Toxoid | Pertussis toxoid | Possible |

| COVID | RNAViral vectors | Messenger RNAGenetic material | Recommended |

Abbreviation: PRP-TT, polysaccharide polyribosomal phosphate tetanus toxoid.

Vaccine Recommendations From the Advisory Committee for Immunization Practices.157

| Vaccine | Recommendation |

|---|---|

| Influenza | -Annual vaccination |

| Parotiditis, rubeola, measles | -1 or 2 doses in patients born after 1957 who have lost immunity |

| Varicella | -Adults without data on previous disease should be given an immunity test; otherwise, administer 2 doses. A booster shot is sufficient for those who have already received 1 dose. |

| Herpes zoster | -1 dose for adults > 60 y |

| Pneumococcal | -1 dose for adults > 65 y |

| Diphtheria and tetanus | -Booster every 10 Y and after a high-risk wound |

| Human papillomavirus | -Recommended for unvaccinated women up to 26 y and unvaccinated men up to 21 y |

| Hepatitis A, hepatitis B, Haemophilus influenzae type B, and meningococcal | -As per vaccine schedule or in individual situations of risk |

Strict adherence to all COVID-19 preventive measures and public health advice is recommended. Accordingly, testing for COVID-19 is recommended in patients with psoriasis who have been in close contact with a positive case, even if they are asymptomatic.

Unless contraindicated, COVID-19 vaccination with supervision by a dermatologist is recommended for all patients with psoriasis. In certain cases, the dermatologist should (or could) provide guidance on optimal vaccination timing and regimens according to the patient's current treatment (see summary of information and recommendations in Table 12).162

GPs Position on COVID-19 Vaccines.162

| # | Comments/recommendations |

|---|---|

| 1 | Currently, there is no evidence that COVID-19 vaccination has a negative effect on the course of psoriasis. |

| 2 | Currently available vaccines are based on technologies that do not pose any risk of infection activation. |

| 3 | Currently available vaccines ARE NOT live attenuated virus vaccines, which are the only vaccines contraindicated in patients on immunosuppressive therapy. |

| 4 | Based on current information, COVID-19 vaccines have a favorable short-term safety profile and similar adverse effects to those seen in other common vaccines. The most common adverse effect is injection site pain. Other relatively common adverse effects are some tiredness or weakness, fatigue, and headache; a high fever is uncommon. These effects usually resolve within a couple of days and respond to paracetamol or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, such as ibuprofen. |

| 5 | COVID-19 vaccines are not recommended in people with a history of allergic reactions to any of their components |

| 6 | Conventional and biologic systemic drugs are not expected to cause any additional complications in association with COVID-19 vaccines. |

| 7 | -Methotrexate and cyclosporin A decrease immune response to some vaccines. Temporary discontinuation of these drugs, with consideration of their half-lives, may be considered before and after vaccination.-Overall, there is evidence that biologic treatments for psoriasis can reduce cell-mediated but not humoral responses to vaccines. There is no evidence, however, that they reduce the protection conferred by COVID-19 vaccination.-TNF inhibitors can reduce the level of antibodies induced by certain vaccines, but they do not have a significant effect on protection conferred.-Ustekinumab, secukinumab, and ixekizumab do not reduce the immunogenicity of vaccines. There are no data on more recent drugs, although it can be assumed that they behave like the other drugs in their class.-In any case, vaccination should always be considered preferable when individualized treatment modifications cannot be made. |

Abbreviation: GPs, Psoriasis Group of the Spanish Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

Leishmaniasis is a chronic, vector-borne infectious disease caused by protozoan parasites of the genus Leishmania that are transmitted to humans via sandfly bites. In Europe, leishmaniasis is most prevalent in Mediterranean countries. The causative species has a significant bearing on clinical manifestations and the host's immune response determines clinical outcomes. Leishmaniasis has been described in association with several immunosuppressive drugs.

A higher prevalence of subclinical leishmaniasis has been described in patients with inflammatory rheumatic diseases under treatment with biologics compared with other immunosuppressive drugs.163 These treatments can cause atypical leishmaniasis manifestations, such as lesions covering large areas of skin and possible mucosal involvement. A targeted history is recommended before a patient from a leishmaniasis-endemic area is started on biologic therapy.

Chagas disease in patients from endemic areas is becoming increasingly common in our setting, probably due to improved access to health care and the availability of more powerful immunosuppressive treatments. Screening of patients at risk should thus be considered before starting immunosuppressive therapy; early treatment with benznidazole and close follow-up to prevent clinical reactivation can be administered if necessary.164

ImmunogenicityDrug immunogenicity (the production of antibodies against a drug) is relatively common in patients treated with biologic agents, including biosimilars. No association with increased toxicity, however, has been demonstrated.165

In some cases, drug immunogenicity can result in a diminished response to treatment, either because the antibodies produced are neutralizing (i.e., they prevent binding to the target) or because they form immune complexes and increase drug clearance. Antibodies are drug-specific and cross-react with respective biosimilars. Although they have been described for all biologics, they may interfere with the efficacy of TNF inhibitors. Antibodies against ustekinumab and IL-17 or IL-23 inhibitors have little or no clinical effect.166 The prevalence of anti-drug antibodies and their effect on efficacy and safety are summarized in Table 13.

Prevalence of Antibodies to Drugs in Studies of Psoriasis.

| Study | Prevalence of antibodies and neutralizing antibodies to drug | Efficacy problems | Safety problems |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adalimumab | |||

| Blauvelt 2018167 | Wk 0–17: 34%Wk 17–51: 45% | No | No |

| Papp 2017168 | -Wk 16: 64% (14% neutralizing)-Wk 20: 60% (11% neutralizing) | Not analyzed | Not analyzed |

| Menter 2008169 | -Wk 52: 9% | Yes (reduced efficacy in some cases) | Not analyzed |

| Brodalumab | |||

| Lebwohl 2015170 | -Wk 52: 2% (0% neutralizing) | No | No |

| Certolizumab pegol | |||

| Pooled analysis of CIMPASI-1 and -2171 | -Wk 48 (200mg): 19%-Wk 48 (400mg): 8% | Yes (reduced efficacy in some cases) | Not analyzed |

| Etanercept | |||

| Griffiths 2017172 | -Wk 12: 2% (0% neutralizing) | No | No |

| Gerdes 2018173 | -Wk 12–30: 0% (0% neutralizing) | Not demonstrated | |

| Tyring 2007174 | -Wk 96: 18% (0% neutralizing) | No | No |

| Guselkumab | |||

| Zhu 2019175 | -Wk 100: 9% | No | No |

| Langley 2018121 | -Wk 60: 9% | Not analyzed | Not analyzed |

| Infliximab | |||

| Reich 2005176 | -Wk 46: 22%-Wk 66: 19% | Yes (reduced efficacy in some cases) | No |

| Ixekizumab | |||

| Reich 2018177 | -Wk 60: 17% (3.5% neutralizing) | Yes (reduced efficacy in some cases) | Not analyzed |

| Gordon 2016119 | -Wk 12: 9% | Yes (reduced efficacy in some cases) | Not analyzed |

| Risankizumab | |||

| SPC6 | -Wk 52: 24% | Yes (reduced efficacy in some cases) | Increased incidence of mild and transient local reactions |

| Secukinumab | |||

| Reich 2017178 | -Wk 60: <0.4% | No | No |

| Tildrakizumab | |||

| Kimball 2020179 | -Wk 52/64 (100mg): 7%-Wk 52/64 (100mg): 8% | Yes (reduced efficacy in some cases) | No |

| Ustekinumab | |||

| Langley 2018121 | -Wk 60: 15% | Not analyzed | Not analyzed |

| Tsai 2011180 | -Wk 36: 4% | Yes (reduced efficacy in some cases) | Not analyzed |

| Griffiths 2010181 | -Wk 64: 4% | Not analyzed | No |

| Leonardi 2008182 | -Wk 76: 5% | Not analyzed | No |

| Papp 2008183 | -Wk 52: 5% | Yes (reduced efficacy in some cases) | |

Abbreviation: SPC, summary of product characteristics.

There is little evidence that biologic therapy in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis is associated with an increased risk of surgical infection or other complications.156 Numerous factors should be taken into account in patients scheduled for elective surgery, such as other risk factors (e.g., poorly controlled diabetes or use of corticosteroids), type of surgery, and psoriasis status. Proactive measures (e.g., adjustment of dosing intervals or temporary discontinuation) should only be taken in the presence of risk factors for infection (e.g., prosthesis, cholecystectomy, cataracts, and implants). These measures are more appropriate for drugs with long administration intervals.

Final ConclusionsData from clinical trials and real-world settings have added to the body of knowledge on the effectiveness, safety, and efficiency of biologic therapies, and highlight the importance of taking into account the different clinical situations described in this updated consensus statement.

As with all long-term immunomodulatory treatments, risk management in patients on biologic therapy should be regularly reviewed and adapted to new knowledge and new mechanisms of action. Accordingly, it is important to draw on evidence-based data to strike a balance between treatment, monitoring, and reasonable guarantees to patients.

FundingThis study was entirely funded by resources from the Spanish Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (AEDV).

Conflicts of interestJosé Manuel Carrascosa has served as a principal investigator/co-investigator and/or received speaker's fees and/or participated on expert or steering committees for Abbvie, Novartis, Janssen, Lilly, Sandoz, Amgen, Almirall, BMS, Boehringer ingelheim, Biogen, and UCB.

Laura Salgado-Boquete has served as a principal investigator/co-investigator and/or received speaker's fees and/or participated on expert or steering committees for AbbvieCelgene, Leo Pharma, Novartis, Janssen, Lilly, Sandoz, Amgen, Almirall, UCB, Pfizer, and MSD.

Lluis Puig has served as a principal investigator/co-investigator and/or received speaker's fees and/or participated on expert committees or as a scientific consultant for Abbvie, Almirall, Amgen, Baxalta, Biogen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, Gebro, Janssen, JS BIOCAD, Leo-Pharma, Lilly, Merck-Serono, MSD, Mylan, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, Roche, Sandoz, Samsung-Bioepis, Sanofi, and UCB.

Elena del Alcázar has served as a principal investigator/co-investigator and/or received speaker's fees for Abbvie, Almirall, Amgen, Celgene, Janssen, Leo-Pharma, Lilly,Novartis, Sanofi, and UCB.