We describe the case of a 54-year-old Bolivian woman who had lived in Spain for 14 years. The patient a history of hypertension, asthma, and urticaria with chronic angioedema that had first appeared 6 years earlier; she had been assessed and treated for the urticaria and angioedema at another care facility. In March 2012, the patient started receiving subcutaneous etanercept (50mg/wk) for treatment of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis that had not responded to treatment with methotrexate and oral corticosteroids. After 3 months, complete response was achieved in the skin and partial response was achieved in the joints. Because of persistent peripheral blood eosinophilia (> 1000/μL), the patient underwent screening for associated diseases. The serologic findings (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay was positive for IgG) indicated Strongyloides stercoralis infestation, which was treated with oral ivermectin (200μg/kg/d for 2 days) in February 2013. Direct parasitological stool examination and stool cultures performed in triplicate were negative before and after treatment. One year later, during follow-up, the patient was screened for Chagas disease, with positive findings in blood tests (enzyme immunoassay and indirect immunofluorescence) and polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Organ involvement was ruled out by a standardized test and the disease stage was classified as indeterminate. Because of the risk of reactivation, etanercept was withdrawn and treatment was initiated with oral benznidazole (5mg/kg/d for 60 days) and biologic therapy was subsequently resumed. In the past 18 months, no reactivation of the infection has been observed (PCR remains negative and serology is positive with lower titers) despite ongoing treatment with etanercept.

Chagas disease, caused by the Trypanosoma cruzi parasite, affects approximately 10 million people worldwide, especially in South America, where it causes thousands of deaths each year. In recent decades, because of migratory flows, the disease has spread to nonendemic areas such as Spain, where the use of biologic therapy is on the rise. In our area, most patients are diagnosed with Chagas disease of indeterminate stage (positive serology, fluctuating parasitemia, and absence of symptoms) and can remain in that stage indefinitely or progress to the symptomatic chronic stage after 10 to 30 years.1 Immunosuppression alters the natural history of the disease, facilitating reactivation and progression to advanced stages. Reactivation is defined as an increase in parasitemia that can be detected by PCR, with the methods of choice being quantitative PCR (a mode not available in our case) or direct examination. The disease can be associated with severe symptoms of organ involvement, such as myocarditis or meningoencephalitis, or it can be asymptomatic. Reactivation has been widely reported in patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, transplant recipients, and patients receiving conventional immunosuppressive therapy. Currently, there is no evidence that corticosteroids at immunosuppressive doses increase the risk of reactivation. In immunosuppressed patients, treatment with benznidazole or nifurtimox is indicated (recommendation grade BII).2 Criteria of cure are not well defined, although the patient is assumed to be cured if successive PCR tests are negative after treatment. Serologic testing is not useful because it can take years to achieve negative seroconversion.1

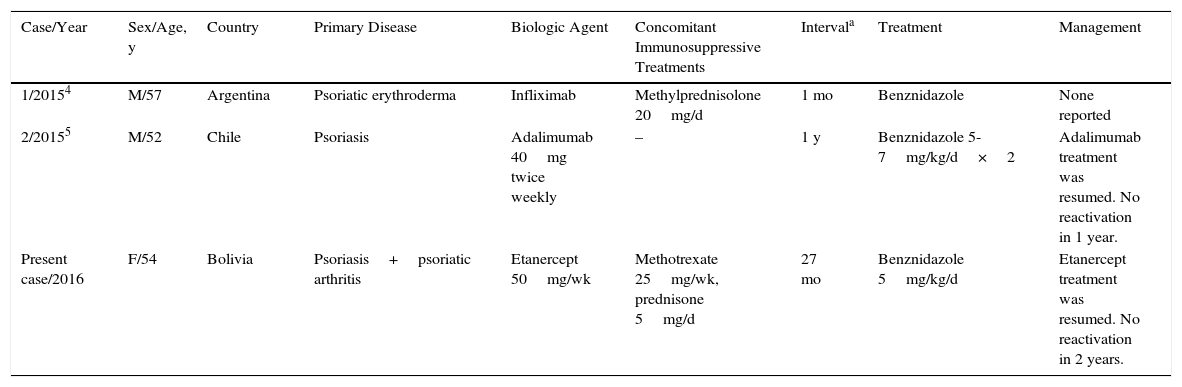

Anti-TNF agents have been associated with an increased risk of opportunistic infections. In the French RATIO registry of nontuberculous opportunistic infections in patients receiving anti-TNF therapy, 45 cases of such infections were detected over a 3-year period. The risk of infection was not statistically significant with any drug, although it was higher with infliximab and adalimumab than with etanercept.3 This risk is still being assessed and more data on reactivation rates of parasitic infections are needed. Only 2 cases of reactivation of Chagas disease in patients receiving biologic therapy have been reported; both patients had psoriasis and were receiving treatment with infliximab and adalimumab, respectively (Table 1).4,5

Reported Cases of Reactivation of Chagas Disease in Patients Receiving Biologic Therapy and Management.

| Case/Year | Sex/Age, y | Country | Primary Disease | Biologic Agent | Concomitant Immunosuppressive Treatments | Intervala | Treatment | Management |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1/20154 | M/57 | Argentina | Psoriatic erythroderma | Infliximab | Methylprednisolone 20mg/d | 1 mo | Benznidazole | None reported |

| 2/20155 | M/52 | Chile | Psoriasis | Adalimumab 40mg twice weekly | – | 1 y | Benznidazole 5-7mg/kg/d×2 | Adalimumab treatment was resumed. No reactivation in 1 year. |

| Present case/2016 | F/54 | Bolivia | Psoriasis+psoriatic arthritis | Etanercept 50mg/wk | Methotrexate 25mg/wk, prednisone 5mg/d | 27 mo | Benznidazole 5mg/kg/d | Etanercept treatment was resumed. No reactivation in 2 years. |

Abbreviations: F, female; M, male.

Little information is available on the need for serologic screening for Chagas disease before the initiation of biological treatment. Salvador et al. recommend screening patients from endemic areas and performing prior treatment with benznidazole in infected patients. During follow-up, the authors recommend closely monitoring patients with PCR for early detection of reactivation.6

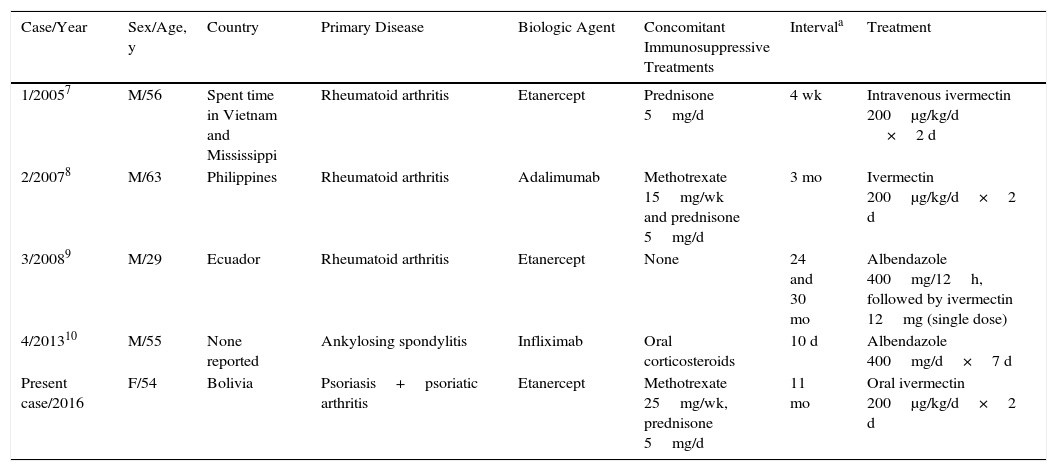

The prevalence of infection with S stercoralis, a human intestinal nematode, has also increased in recent years in Spain. The infestation is endemic in tropical and subtropical regions, but there are also endemic areas in Spain, especially on the Mediterranean coast. Diagnosis is made by stool culture on agar plate and/or serologic testing. Immunosuppressed patients are at risk of hyperinfestation syndrome, which is associated with high mortality.3 Four cases have been reported in patients receiving anti-TNF therapy (Table 2).7–10 In patients from endemic areas, it appears that screening for S stercoralis before the start of biologic therapy would be advisable and, in the event of infestation, treatment should be initiated with oral ivermectin (200μg/kg/d for 2 consecutive days), which has been shown to be the most effective therapy.3

Reported Cases of Strongyloides stercoralis Infestation in Patients Receiving Biologic Therapy and Treatment.

| Case/Year | Sex/Age, y | Country | Primary Disease | Biologic Agent | Concomitant Immunosuppressive Treatments | Intervala | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1/20057 | M/56 | Spent time in Vietnam and Mississippi | Rheumatoid arthritis | Etanercept | Prednisone 5mg/d | 4 wk | Intravenous ivermectin 200μg/kg/d ×2 d |

| 2/20078 | M/63 | Philippines | Rheumatoid arthritis | Adalimumab | Methotrexate 15mg/wk and prednisone 5mg/d | 3 mo | Ivermectin 200μg/kg/d×2 d |

| 3/20089 | M/29 | Ecuador | Rheumatoid arthritis | Etanercept | None | 24 and 30 mo | Albendazole 400mg/12h, followed by ivermectin 12mg (single dose) |

| 4/201310 | M/55 | None reported | Ankylosing spondylitis | Infliximab | Oral corticosteroids | 10 d | Albendazole 400mg/d×7 d |

| Present case/2016 | F/54 | Bolivia | Psoriasis+psoriatic arthritis | Etanercept | Methotrexate 25mg/wk, prednisone 5mg/d | 11 mo | Oral ivermectin 200μg/kg/d×2 d |

Abbreviations: F, female; M, male.

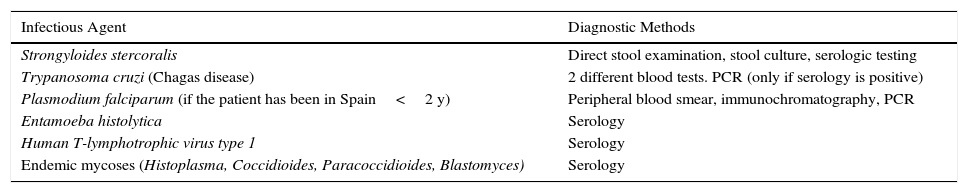

In conclusion, we consider that pre-screening for Chagas disease and Strongyloides infestation, as is already established for detection of latent tuberculosis infection in international clinical guidelines for biologic therapy, is necessary in patients from endemic areas or who have lived in endemic areas (Table 3). The aim of this screening is to decrease the morbidity and mortality that these diseases could bring to our area in the coming years.

Screening for Nontuberculous Opportunistic Infections Recommended in Patients From Endemic Areas Before Initiation of Biologic Therapy.

| Infectious Agent | Diagnostic Methods |

|---|---|

| Strongyloides stercoralis | Direct stool examination, stool culture, serologic testing |

| Trypanosoma cruzi (Chagas disease) | 2 different blood tests. PCR (only if serology is positive) |

| Plasmodium falciparum (if the patient has been in Spain<2 y) | Peripheral blood smear, immunochromatography, PCR |

| Entamoeba histolytica | Serology |

| Human T-lymphotrophic virus type 1 | Serology |

| Endemic mycoses (Histoplasma, Coccidioides, Paracoccidioides, Blastomyces) | Serology |

Abbreviation: PCR, polymerase chain reaction.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

We thank the Microbiology Department of Hospital Universitario La Paz for collaboration on this article.

Please cite this article as: González-Ramos J, Alonso-Pacheco ML, Mora-Rillo M, Herranz-Pinto P. Necesidad de cribado de enfermedad de Chagas y de infestación por Strongyloides previo a inicio de terapia biológica en países no endémicos. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2017;108:373–375.