Calcified deposits in the skin are rare.1 When they are formed of mature bone with the presence of trabeculae they are called ossification, whereas deposits of amorphous material are called calcification. The presence of calcium on histology is diagnostic, though this can be difficult in some cases. Ultrasound is a rapid, noninvasive technique that provides in vivo information that can be very useful for the study of these lesions.2 We present the case of a 71-year-old woman whose relevant past history included systemic lupus, kidney failure, and secondary hyperparathyroidism. She was on long-term treatment with risendronate, torasemide, allopurinol, and prednisone. She was seen for painful lesions that had arisen on her legs 4 months earlier.

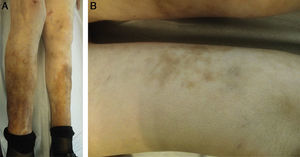

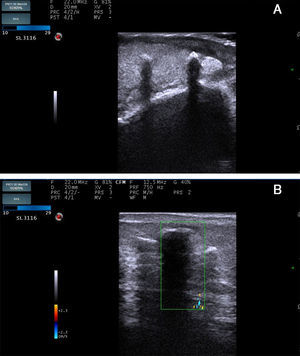

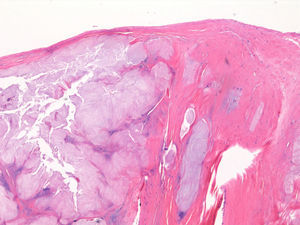

On physical examination, both legs were indurated and presented hyperpigmentation (Fig. 1A) with hard, well-defined subcutaneous nodules over which there were brownish-erythematous macules with a reticular pattern (Fig. 1B). The blood tests gave the following results related to her underlying disease: hemoglobin, 10.7mg/dL; creatinine, 1.8mg/dL; urea, 119mg/dL; sodium, 138mmol/L; potassium, 4.7mmol/L; parathyroid hormone, 114pg/mL; calcium, 9mg/dL; phosphorus, 3.7mg/dL. Ultrasound study (Esaote My Lab One with a variable frequency linear array of 18-22MHz with a lateral resolution of 240μm) demonstrated a thickened and hypoechoic dermis, suggestive of inflammation, and hyperechoic deposits with a density similar to bone and with a linear morphology. These deposits were located in the dermis and in the subcutaneous cellular tissue and left an acoustic shadow (Fig. 2A). Flow was absent on Doppler study (Fig. 2B). Skin biopsy revealed fibrotendinous tissue with mature cartilage (Fig. 3).

A, Ultrasound image. B mode: sagittal section showing increased thickness and decreased echogenicity of the dermis, compatible with inflammation, and hyperechoic deposits with a linear morphology that produce an acoustic shadow. The deposits are located in the dermis and in the subcutaneous cellular tissue. B, Ultrasound image. Doppler study: absence of flow.

Despite the lack of histological confirmation, the diagnosis of calcium deposits was supported by the clinical manifestations and the ultrasound findings. The patient died due to rupture of an aneurysm of an internal iliac artery and no further tests could be performed.

Soft-tissue calcifications have been associated with rheumatologic disorders, although they are considered rare in systemic lupus erythematosus.3 Since 1975, soft-tissue calcifications have been classified into various subtypes: metastatic, dystrophic, idiopathic, tumoral, and calciphylaxis. Metastatic calcifications appear in healthy tissue and are due to changes in phosphorus and calcium metabolism. They are associated with hyperparathyroidism and tumors. Dystrophic calcifications develop without changes in phosphorus and calcium metabolism, in tissues previously damaged by diseases such as lupus, scleroderma, or dermatomyositis. Tumoral calcifications are due to a genetic disorder, with lesions in pressure areas and close to joints. Idiopathic calcifications develop in otherwise healthy individuals. Calciphylaxis is characteristic of patients with advanced chronic kidney failure and is due to calcification of the walls of small vessels.4 Ossification is much rarer and has primary forms (Albright hereditary osteodystrophy and osteoma cutis) and secondary forms that arise in scars, tissues affected by collagen diseases, and inflammatory lesions due to metaplasia of a preexisting lesion.1 The deposits are usually asymptomatic and are detected as incidental findings on x-ray. Lesions vary from whitish papules or nodules of firm consistency to skin ulcers. Ossification is harder than calcification. Livedo racemosa is a rare finding and is associated with altered venous drainage.5 Advanced lesions can cause pain, inflammation, joint deformity, and nerve entrapment. The differential diagnosis is broad. Pilomatrixomas, calcified epidermal cysts, and foreign body reactions must be ruled out when the lesions are localized, whereas panniculitis, lipodermatosclerosis, vasculitis, and vascular ulcers must be excluded when there are widespread or ulcerated lesions with inflammatory signs. To further complicate the situation, any of these dermatoses can coexist with the calcium deposits. On ultrasound, the deposits are hyperechoic, with a similar density to bone, and they produce a posterior acoustic shadow in the case of ossification. Calcifications are less echogenic.5 Skin deposits are usually oval, whereas they are linear when they arise in blood vessel walls. Ultrasound is considered to be the investigation of choice for the early diagnosis and follow-up of calcium deposits, as it is more sensitive and specific than radiography.6 Histology is the gold standard. Treatment has not been standardized. Surgical resection, intralesional corticosteroids, carbon dioxide laser therapy, and even intravenous immunoglobulin have been used to treat localized lesions, whereas diltiazem, probenecid, minocycline, aluminum hydroxide, and the bisphosphonates have been employed in widespread lesions, with favorable results in isolated cases.7 In our patient it was not possible to determine whether the lesions were calcifications or ossifications, though the clinical manifestations and ultrasound findings would suggest they were multiple secondary ossifications. Through our presentation of this case, we would like to draw attention to the increasing importance of skin ultrasound and its indications, particularly for the investigation of calcium deposits, as it has a very high sensitivity for these lesions and can be the key to diagnosis if histology is not conclusive.

Please cite this article as: Lorente-Luna M, Alfageme Roldán F, González Lois C. Depósitos cálcicos cutáneos diagnosticados mediante ecografía. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2015;106:586–588.