The pigmented purpuric dermatoses (PPDs) are a group of benign, chronic diseases. The variants described to date represent different clinical presentations of the same entity, all having similar histopathologic characteristics. We provide an overview of the most common PPDs and describe their clinical, dermatopathologic, and epiluminescence features. PPDs are both rare and benign, and this, together with an as yet poor understanding of the pathogenic mechanisms involved, means that no standardized treatments exist. We review the treatments described to date. However, because most of the descriptions are based on isolated cases or small series, there is insufficient evidence to support the use of any of these treatments as first-line therapy.

Las dermatosis purpúrico pigmentadas (DPP) son un grupo de enfermedades benignas y de curso crónico. Las variantes descritas representan distintas formas clínicas de una misma entidad con unas características histopatológicas comunes para todas ellas. Exponemos a continuación un resumen de las variedades más frecuentes, sus características clínicas, dermatopatológicas y de epiluminiscencia. Al tratarse de una entidad clínica poco frecuente, benigna, y no conocerse claramente los mecanismos patogénicos de la misma, no existen tratamientos estandarizados. Se revisan los tratamientos publicados hasta el momento, la mayoría de ellos basados en casos aislados o pequeñas series de casos, sin poder establecer un nivel de evidencia suficiente como para ser recomendado ninguno de ellos como tratamiento de elección.

The pigmented purpuric dermatoses (PPDs) are a rare group of chronic, benign diseases characterized by multiple petechiae on hyperpigmented, yellowish-brown macules.1 The different variants are distinct clinical forms of the same entity with similar histopathologic features.2,3

There are 5 classic variants: Schamberg disease (progressive PPD), eczematoid purpura of Doucas and Kapetanakis (pruritic purpura), pigmented purpuric lichenoid dermatosis of Gougerot and Blum, lichen aureus (lichen purpuricus), and Majocchi disease (purpura annularis telangiectodes).1 Less common variants are granulomatous PPD, itching purpura of Loewenthal, linear PPD, transitory PPD, and familial PPD.2

EpidemiologyPPDs are rare and predominantly affect adults,1 although cases have been reported in children.4 The most common variant in both adults and children is Schamberg disease. PPDs, and linear forms in particular,6 are generally more common in men.1 Majocchi disease is more common in women.

Etiology and PathogenesisAlthough the causes of the PPDs are unknown, a range of triggering factors have been proposed, including exercise, venous hypertension, diabetes mellitus, infections,2,7 and various medications (Table 1).8 An association with dyslipidemia and autoimmune diseases has been reported for granulomatous PPD.9 In most cases, however, no cause is identified.10

Drugs Associated With the Pigmented Purpuric Dermatoses.

| Sedatives | Phenobarbital, chlordiazepoxide, meprobamate |

| Vitamins | Thiamine (B1) |

| Diuretics | Furosemide |

| Cardiovascular drugs | Nitroglycerine, bezafibrate, hydralazine, dipyridamole, sildenafil |

| Antibiotics | Ampicillin |

| Analgesics | Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, aspirin, acetaminophenol |

| Stimulants | Pseudoephedrine |

| Hormones | Medroxyprogesterone acetate |

| Antidiabetic drugs | Glipizide |

| Chemotherapy agents | Topical 5-fluorouracil |

| Antivirals | Interferon α |

| Retinoids | Isotretinoin |

Source: Kaplan et al.8

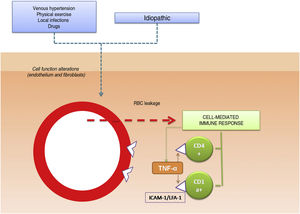

Capillary dilation and fragility have been attributed a possible pathogenic role in PPDs.10 It has been hypothesized that the cells responsible for these disorders are cells involved in blood vessel structure, such as fibroblasts and endothelial cells. Whether through activation (e.g., high intravascular pressure) or spontaneously, the function of these cells may be altered, causing red blood cells (RBCs) to leak through the vessel walls,11 triggering a cell-mediated hypersensitivity reaction. Cell-mediated immune response would therefore appear to have a fundamental role in the pathogenesis of PPDs.12,13 The perivascular inflammatory infiltrate is made up of CD4+ T cells14 (with reduced CD7 expression15) and CD1a+ dendritic cells.12

The pathogenic role of cell adhesion molecules in PPDs has also been analyzed in several studies. CAMs are membrane proteins that interact with specific ligands that provide and maintain contact between different cells and between cells and extracellular matrix proteins. High expression levels have been observed for adhesion molecules LFA-1 (lymphocyte function antigen-1) and ICAM-1 (intercellular adhesion molecule-1) in inflammatory cells and for ICAM-1 and ELAM-1 (endothelial leukocyte adhesion molecule- 1)12 in endothelial cells. T cells activated by an antigenic stimulus would thus adhere to endothelial cells, fibroblasts, and keratinocytes.16 Cytokines produced by leukocytes (e.g., tumor necrosis factor α) can trigger the expression of these adhesion molecules (Fig. 1).

Etiologic and pathogenic mechanism. One of the most widely accepted hypotheses is that T cells are activated by an antigenic stimulus and bind to endothelial cells, fibroblasts, and keratinocytes through the expression of adhesion molecules. TNF-α indicates tumor necrosis factor α ; ICAM-1, intercellular adhesion molecule-1; LFA-1, lymphocyte function antigen-1.

The above cytokines may also result in a decreased release of the endothelial plasminogen activator and/or an excessive increase in the plasminogen activator inhibitor,17 leading to the reduced fibrinolytic activity and intraperivascular deposition of fibrin observed in PPDs.18

Direct immunofluorescence may show fibrinogen, immunoglobulin M, and/or C3 deposition in the superficial dermal vessels.10

Another hypothesis that has emerged in recent years is that PPDs may represent an insidious epitheliotropic T-cell alteration. This theory is supported by the observation of epidermotropism or a monoclonal pattern in the inflammatory infiltrate.15,19 There have even been some reports of progression to mycosis fungoides.20–22 As it is difficult to distinguish between purpuric mycosis fungoides and monoclonal PPD, it is essential to integrate clinical, molecular, and histopathologic findings.15,20,23 Poikiloderma, pruritus, coalescing plaques, a duration of more than 1 year, a monoclonal pattern, and decreased CD7 and CD62 L expression in the infiltrate should all raise suspicion of disease progression, even in the absence of overt lymphocytic atypia.15,24 Some authors opt to treat disseminated and monoclonal DPP as early-stage mycosis fungoides.

Clinical VariantsProgressive PPD or Schamberg Disease1,2In progressive PPD or Schamberg disease, lesions usually appear on both lower extremities, but they can also affect the trunk, arms, thighs, or buttocks. They present as orange-red macules with peripheral purpuric spots resembling grains of cayenne pepper (Fig. 2A and B); these spots acquire a yellowish-brown color as they progress. The lesions are generally asymptomatic, although some patients describe pruritus. They follow a chronic course with numerous relapses and remissions.

Pruritic Purpura or Eczematoid Purpura of Doucas And Kapetanakis1,25Pruritic purpura or eczematoid purpura of Doucas and Kapetanakis is the most extensive and pruritic variant of the PPDs. It mostly affects the lower extremities and is clinically similar to Schamberg disease, with purpuric or petechial macules but with a scaling surface. Eczematoid purpura of Doucas and Kapetanakis has been associated with allergic contact dermatitis to rubber and clothing. Onset is rapid (15–30 days) and the lesions can last for months or years.

Pigmented Purpuric Lichenoid Dermatosis of Gougerot and Blum1,2,26Lichenoid pigmented purpuric dermatosis of Gougerot and Blum is characterized by violaceous lichenoid papules that tend to merge, forming large plaques that are usually located on the legs but may affect the trunk. The condition follows a chronic course and usually affects elderly men. It should be distinguished from Kaposi sarcoma.

Lichen Aureus or Lichen Purpuricus1,2,27Lichen aureus or lichen purpuricus is a more localized variant of PPD. Lesions are persistent and are typically solitary or small in number. Lichen aureus is characterized by the sudden appearance of small yellow-orangish papules with a lichenoid appearance and a tendency to coalesce into plaques measuring between 1 and 20 cm associated with millimetric purpuric lesions (Fig. 3). The condition mostly affects the lower extremities, but lesions can occur on any part of the body. They are usually asymptomatic. Zosteriform28 and segmental variants along the lines of Blaschko29 or following the course of the saphenous30 or cephalic veins31 have been described in children and adolescents.

Purpura Annularis Telangiectodes or Majocchi Disease1,2,25Purpura annularis telangiectodes or Majocchi disease presents with annular red-violaceous macules (Fig. 4), followed by darker red telangiectatic puncta. The lesions extend peripherally and their center gradually fades and may acquire an atrophic appearance. The eruption begins in the lower extremities and then spreads to the trunk and arms; it is characterized by large numbers of lesions. A variant known as arciform purpura annularis telangiectodes featuring fewer but larger lesions with a characteristic arched morphology has been described.32

Other VariantsHersch and Schwayder33 described what is considered to be a rare linear, unilateral form that must be differentiated from linear forms of Schamberg disease and lichen aureus. Higgins and Cox34 described a quadrantic form they attributed to a vascular obstruction in the pelvis.

There have also been reports of a transitory variant35 including entities such as angioma serpiginosum,36 which is an uncommon vascular disorder that usually begins in childhood, is more common in females, and shows evidence of estrogen dependence. Angioma serpiginosum is characterized by multiple asymptomatic red-purpuric macules arranged in small groups following a serpiginosum pattern along the extremities.

Itching purpura of Loewenthal,37 which has only been described in adults, is considered a more symptomatic variant of Schamberg disease.

Granulomatous PPD, described by Saito,38 is a histopathologic form that is more common in women and is clinically indistinguishable from other DPPs.

Finally, there have been reports of autosomal dominant familial forms of Schamberg disease and purpura annularis telangiectoides.39

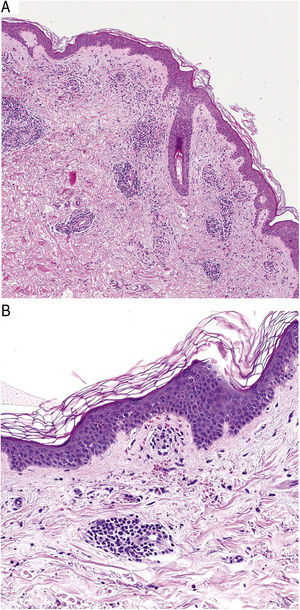

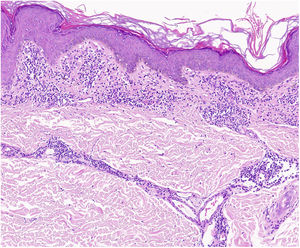

HistopathologyHistopathologically, PPDs are characterized by a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate centered on the superficial small vessels. Other typical findings are endothelial swelling, luminal narrowing,10 extravasated RBCs, and hemosiderin-laden macrophages (Fig. 5 A and B). Perls and Fontana-Masson staining shows hemosiderin (iron) deposits in the superficial dermis, setting DPP apart from stasis dermatitis, which has deeper deposits.2

A characteristic finding of lichen aureus is an intact epidermis separated from a band-like dermal infiltrate by an area of spared connective tissue (Grenz area)27 (Fig. 6). This infiltrate is also typical in pigmented purpuric lichenoid dermatosis of Gougerot and Blum.26 Eczematoid purpura of Doucas and Kapetanakis, by contrast, features epidermal spongiosis and neutrophils in the infiltrate.25 Granulomatous PPD is characterized by a perivascular granulomatous infiltrate overlying typical features.38 A comparison of clinical features, location, and histopathologic findings for the most common variants of PPD is provided in Table 2.

Clinical and Histopathologic Characteristics of the Pigmented Purpuric Dermatoses.

| Variant | Clinical Presentation | Location | Histopathologic Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Schamberg disease | Red-orange macules with peripheral spots resembling grains of cayenne pepper | Lower limbs and occasionally trunk, arms, thighs, and buttocks | Lymphocytic infiltrate involving the superficial small vessels, extravasated red blood cells, and hemosiderin-laden macrophages |

| Eczematoid purpura of Doucas and Kapetanakis | Similar to manifestations of Schamberg disease but with scaling and intense itching | Lower limbs | Infiltrate with higher number of neutrophils and epidermal spongiosis |

| Pigmented purpuric lichenoid dermatosis of Gougerot and Blum | Violaceous lichenoid papules that merge to form plaques | Lower limbs | Band-like dermal infiltrate |

| Lichen aureus | Isolated persistent red-orange plaque and purpuric lesions | Lower limbs | Unchanged epidermis and band-like dermal infiltrate with Grenz area |

| Majocchi disease | Peripherally extending plaques with telangiectatic punta at edges and fading in the central area | Lower limbs and trunk | Identical to Schamberg disease |

While some authors1,13 consider capillaritis to be a defining feature of DPPs, Ackerman40 does not believe this to be the case as there is an absence of fibrin in the luminal wall and thrombi in the lumina.

DiagnosisIn addition to skin biopsy, a blood test is recommended to rule out thrombocytopenia, clotting or autoimmune disorders (antinuclear antibodies, rheumatoid factor), and chronic infections (anti-HCV and anti-HBsAg).2

Differential DiagnosisThe differential diagnosis should include other conditions featuring purpuric manifestations involving the lower extremities. These entities and their main characteristics are summarized in Table 3.

Differential Diagnosis for the Pigmented Purpuric Dermatoses.

| Clinical Entities | Main characteristics |

|---|---|

| Drug-hypersensitivity reactions | Recent use of causative drug |

| Carbamazepine, meprobamate, chlordiazepoxide, furosemide, nitroglycerine, vitamin B1, and topical 5-fluorouracil | |

| Purpuric contact dermatitis to clothing | Lesions confined to areas of the skin in contact with clothing; intense itching |

| Wool, coloring agents | |

| Venous stasis purpura | Signs of chronic venous insufficiency: swelling, varicose veins, feeling of heaviness, venous ulcers |

| Hemosiderin deposition in deep dermis | |

| Purpura due to thrombocytopenia | Associated with platelet count < 100–150000/μL |

| Senile purpura | In elderly patients, purpura can be associated with antiplatelet, anticoagulant, or corticosteroid use |

| Purpuric exanthema due to viral infection | Other signs of infection |

| Leukocytoclastic vasculitis | Palpable purpuric lesions |

| On histology: fibrinoid necrosis, endothelial swelling, and leukocytoclasis | |

| Schönlein-Henoch purpura | Age, 3–15 years; symmetric purpura affecting legs and buttocks; joint and abdominal pain |

| Kaposi sarcoma | Affects elderly or immunosuppressed patients |

| On histology: spindle cells in the dermis forming irregular vascular lumina | |

| Purpuric mycosis fungoides | Onset > 1 year; disseminated, monoclonal profile in infiltrate and loss of CD7 |

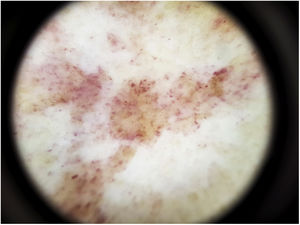

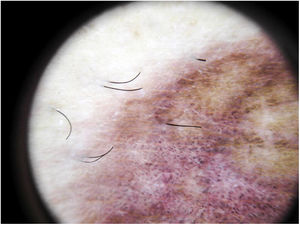

The most common dermoscopic finding is a diffuse coppery-red background that histopathologically corresponds to the lymphocytic dermal infiltrate, extravasated RBCs, and hemosiderin-laden macrophages.41 Other findings include red globules and dots, which can be explained by the extravasated RBCs, the increased number of blood vessels, and the dilation of these vessels42 (Fig. 7). Brown dots are observed in almost 50% of patients and correspond to the spherical or elliptical arrangement of melanocytes and melanophages at the dermoepidermal junction. In a third of cases, dermoscopy shows a pigmented pseudo-network that corresponds to the hyperpigmented basal cell layer and incontinentia pigmenti in the papillary dermis. Specific dermoscopic findings reported for lichen aureus include a coppery-red background with brown and red dots and globules, gray dots, and a pseudo-network comprising interconnected pigmented lines43 (Fig. 8).

TreatmentConsidering that DPPs are benign and no standardized treatments with proven effectiveness exist, the risks and benefits of any treatment should be carefully weighed up.

Due to the benign, largely asymptomatic nature of the DPPs, no treatment is an option.4 Treatment, however, is often called for because of the chronic nature of the disease, its physical and psychological impacts, and the presence of extensive lesions or itching.

Most of the treatment recommendations are based on small case series, and none of them are backed by sufficient evidence to be considered a universal treatment.

A range of topical and systemic treatments, detailed below, have been described in small series and case reports.

Topical TreatmentsTopical CorticosteroidsTopical corticosteroids are the most common treatments described and have been observed to reduce itching and in some cases clear lesions.2,4

The most widely used agents are medium- and high-potency corticosteroids (clobetasol and methylprednisolone aceponate)

Topical Calcineurin InhibitorsTopical application of tacrolimus44 and pimecrolimus45 for several months has been found to resolve lichen aureus.

Given the chronic nature of PPD lesions and the need for long-term treatment, calcineurin inhibitors can be considered a good alternative to topical corticosteroids for clearing or resolving lesions.

PhototherapyPhototherapy is a good option for treating extensive disease or PPD that does not respond to topical corticosteroids or calcineurin inhibitors.

It has been postulated that phototherapy may be effective because it produces an immunomodulatory effect that modifies T-cell activity and reduces the production of interleukin 2, resulting in improvement.46

Psoralen and UV-A (PUVA) treatment has been used successfully in patients with Schamberg disease, lichenoid purpuric dermatosis, and lichen aureus. In the series published to date, between 7 and 29 sessions with cumulative doses ranging from 16 to 49 J/cm2 have been needed to achieve remission. Retreatment has also proven effective, and in some cases maintenance treatment over several months has been necessary to prolong response.2,47–49

Narrowband UV-B phototherapy with cumulative doses of between 11 and 49 J/cm2 administered in 24 to 60 sessions has produced favorable responses in patients with different clinical variants of DPP. As with PUVA treatment, there have been reports of recurrence after treatment discontinuation but good response to retreatment.46,50,51

Narrowband UV-B therapy is considered to be a good option because of its few adverse effects and good tolerability profile. It should therefore be borne in mind as an option for pediatric patients, patients with extensive lesions, and patients resistant to topical treatments.5,52

Systemic TreatmentsPentoxifyllineThere have been reports of PPD responding to oral pentoxifylline. It has been suggested that pentoxifylline may be effective because it inhibits T-cell adherence to the vascular endothelium by interaction with ICAM-1.53,54

Pentoxifylline has been used alone, at a dose of 400 mg twice or three times daily for 2 to 3 months,42,43 or in combination with other drugs such as prostacyclins (prostaglandin I1)55 and oral corticosteroids.56 Pentoxifylline has also been found to be ineffective in the treatment of DPPs.57

Ascorbic Acid and Bioflavonoids (Rutin/Rutoside)As ascorbic acid and bioflavonoids increase collagen production, thereby reducing vascular permeability and improving the vascular endothelial barrier function, high doses of vitamin C combined with a flavonoid glycoside (like rutoside/rutin), present in citrus fruits, administered over several months have resulted in clinical improvements and in some cases resolution.58

Other TreatmentsThere have been isolated reports of response to various systemic treatments, such as griseofulvin,59 colchicine,60 methotrexate,61 and ciclosporin.62

ConclusionsThe DPPs are a common dermatological condition and have a major impact on patient quality of life due to both symptoms and cosmetic concerns. Although the different variants are clinically very similar, there are a number of clinical, histopathologic, and dermoscopic characteristics that help to establish a more specific diagnosis.

Finally, while there is insufficient evidence in the literature to recommend any treatment as a first-line treatment, numerous options exist that can achieve considerable improvements.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

We would like to thank Dr. Valero Torres from the Pathology Laboratory of Hospital Clínico Lozano Blesa for his help with the histopathologic analysis.

Please cite this article as: Martínez Pallás I, Conejero del Mazo R, Lezcano Biosca V. Dermatosis purpúricas pigmentadas. Revisión de la literatura científica. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2020;111:196–204.