Macular arteritis was first described in 2003 by Fein et al.1 Since then, fewer than 15 cases have been reported. The disease mainly affects women with a mean age of 40 years2 and usually presents as vaguely oval and pigmented macules on the legs.

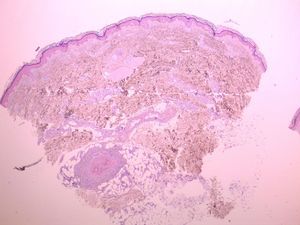

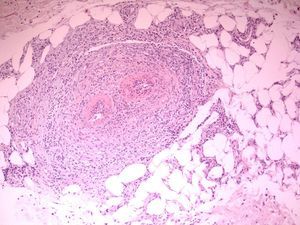

Macular arteritis is confirmed by microscopy, which shows lymphocytic vasculitis selectively affecting the arterioles at the dermal subcutaneous junction. Macular arteritis is also known as lymphocytic thrombophilic arteritis because of the induction of endothelial swelling, luminal stenosis, and, occasionally, concentric fibrin deposition.1–3 Laboratory analyses reveal antinuclear antibodies in 30% of cases and anticardiolipin antibodies in up to 60%, although no apparent correlation with other manifestations of antiphospholid syndrome has been found.2,3

We present the case of a 61-year-old woman with no past history of interest who consulted for slowly progressive pigmented macules with poorly defined borders that had begun to appear 3 years earlier (Fig. 1). Biopsy revealed lymphocytic vasculitis selectively affecting the arterioles at the dermal subcutaneous junction (Fig. 2), with very noticeable lymphocytic cuffing, marked endothelial swelling, and narrowing of the vascular lumen, in which concentric fibrin deposition was visible (Fig. 3). The workup comprised a complete coagulation study, serology for autoimmune diseases, hepatotropic viruses, human immunodeficiency virus, and syphilis, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, antineutrophilic cytoplasmic antibody, and protein electrophoresis, all of which yielded normal or negative results. These findings led us to make a diagnosis of macular arteritis. The lesions stabilized or abated very slightly without treatment during the summer months, and no other cutaneous or systemic manifestations were observed after 1 year of follow-up.

Macular arteritis may be considered a minor form of antiphospholipid syndrome, although its only aspect in common with this condition is the occasional slight increase in anticardiolipin antibody titer, since the patient does not present the characteristic manifestations of thrombophilia or underlying thrombotic vasculopathy.3 It seems that increased anticardiolipin antibody titer is associated with the vascular insult, although it has also been recorded in 7% of healthy patients and after episodes of infection.1,3

Potentially associated conditions include thrombophilic and lymphocytic vasculitis with systemic involvement, such as Degos disease and livedo vasculitis, or Sneddon syndrome2,3; however, none of the reported cases of macular arteritis involved extracutaneous manifestations, and the lesions observed in this condition are completely different from the porcelain-like atrophic or livedoid lesions that are characteristic of the first 2 conditions. The fibrin ring observed under microscopy seems to be a focal phenomenon3 and is in no way comparable to the intense multisystem thrombosis observed in Degos disease and Sneddon syndrome.

Differentiation of macular arteritis from cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa (PAN) is more complicated. Despite its name, cutaneous PAN does not include the multisystem manifestations of classic or microscopic PAN. In addition, the disease selectively affects the arterioles of the dermal subcutaneous junction, as was the case in our patient.3 There are characteristic features that help to differentiate macular arteritis from cutaneous PAN, namely, the clinical manifestations, with the presence of livedo reticularis, nodules, and ulceration in PAN. The changes in the microscopic findings over time also appear to differ between macular arteritis and PAN. The initial infiltrate in PAN has abundant polymorphonuclear cells, but this changes to a lymphohistiocytic infiltrate, and there are also differences in the sites of the lesions, which are localized to the vascular bifurcations in PAN, with intense focal necrosis that can manifest as a rosette pattern with the formation of microaneurysms. None of these findings have been reported in macular arteritis.2 However, there have been cases reported as lymphocytic thrombophilic arteritis that, despite presenting clinical features (livedo rash) and histological features (residual nuclear dust together with a lymphohistiocytic infiltrate and a vascular rosette pattern) of PAN, were very probably genuine cutaneous PAN.3,4

In the case we report, the cutaneous manifestation, namely, pigmented macules on the thighs, suggests a diagnosis of macular arteritis. These lesions are characteristic of macular arteritis and clearly differ from the habitual manifestations of PAN. In addition, histopathology in our patient revealed the absence of an acute phase with abundant polymorphonuclear cells. It is questionable whether macular arteritis has sufficient defining features to be considered a separate entity from cutaneous PAN; however, given our currently limited knowledge of the pathogenic and immunologic mechanisms underlying these conditions, we cannot rule out the possibility that macular arteritis is at one end of the spectrum5 that includes systemic PAN as its most relevant disease. The range of potential manifestations is affected by immune complex size, localization to venous/arterial endothelium, selectivity for skin or other organs, chemotactic potential for different types of cells, and persistence of the antigen (eg, drugs, hepatitis B or C virus, and neoplasms),5 as well as the ability to eliminate it.

Please cite this article as: Valverde R, et al. Arteritis macular: ¿en el espectro de la poliarteritis nudosa cutánea? Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2013;104:263–5.