Postherpetic neuralgia is the most frequent and best-known complication of herpes zoster. Lesser-known complications include encephalitis, meningitis, and peripheral motor paralysis.1 Horner syndrome (miosis, ptosis, enophthalmos, and/or anhidrosis) is a rare complication of cervical and thoracic herpes zoster.

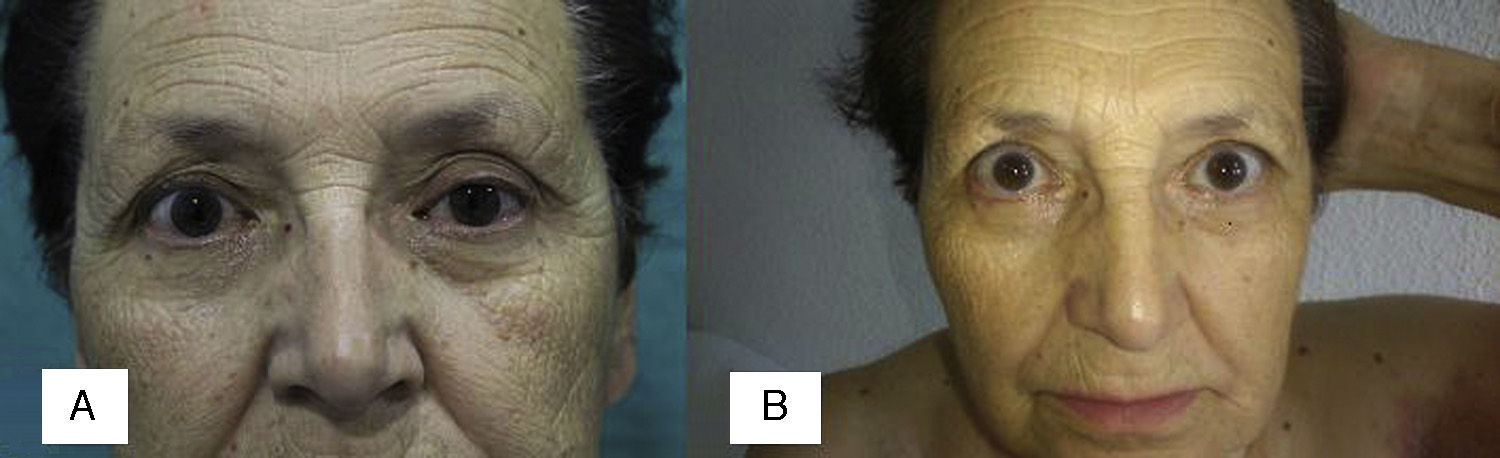

We report the case of a 74-year-old woman who presented to our emergency department with a 10-day history of progressively appearing painful lesions on her left arm, left chest, and left upper back. Past history included hiatal hernia and endometrial adenocarcinoma treated 11 years earlier with total hysterectomy, bilateral adnexectomy, bilateral pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy, and adjuvant radiotherapy. She reported no systemic symptoms and no motor symptoms involving the arm. Physical examination revealed clustered vesicles and bullae on an erythematous base with some areas of surface erosion, in a C8 and T1 dermatomal distribution on the left side (Fig. 1). In addition, the patient had ptosis of the left upper eyelid; her left pupil was smaller than the right, and her skin was drier on the left side of her face (Fig. 2A), with no other focal neurologic abnormalities. Biochemistry, a complete blood count, and a chest radiograph yielded no findings of interest. The patient was diagnosed with cervical and thoracic herpes zoster associated with Horner syndrome of the left eye. Antiviral therapy was initiated with 1g of valacyclovir every 8hours for 7 days, together with an alternating regimen of 1g of acetaminophen every 8hours and 575mg of metamizole every 8hours for pain. The skin lesions gradually improved, and Horner syndrome resolved within 15 days with no sequelae (Fig. 2B).

The best-described ocular complications of herpes zoster include swelling of the eyelid, keratitis, conjunctivitis, iridocyclitis, episcleritis, retinal necrosis, central retinal artery occlusion, and ophthalmoparesis.2 Horner syndrome, or oculosympathetic palsy, is characterized by ptosis, miosis, anhidrosis, and/or enophthalmos, and was classically attributed to space-occupying lesions in the vertex of the lung, such as Pancoast tumor. It has seldom been described as an ophthalmic or thoracic complication of herpes zoster.3

In the spinal cord, the ocular sympathetic pathway originates in the cells of the intermediolateral cell column at the level of segments C8 to T2. Preganglionic fibers emerge from the spinal cord following the ventral roots to form the sympathetic chain, pass through the stellate ganglion, and synapse in the superior cervical ganglion.4 Given that the agent of herpes zoster infection lies dormant in the dorsal roots of the sensory ganglia of the central nervous system, the most plausible theory for the pathogenesis of Horner syndrome secondary to thoracic herpes zoster is that either the spinal cord or its ventral roots become inflamed owing to viral activation that spreads by contiguity.5,6 However, in the case of herpes zoster ophthalmicus, other potential mechanisms have been considered, including ischemic neuritis of the third, fourth, or sixth cranial nerves; a mesencephalic lesion caused by axonal spread of the virus; inflammation by contiguity leading to myositis; or even immune-mediated demyelination due to local or remote viral spread.7

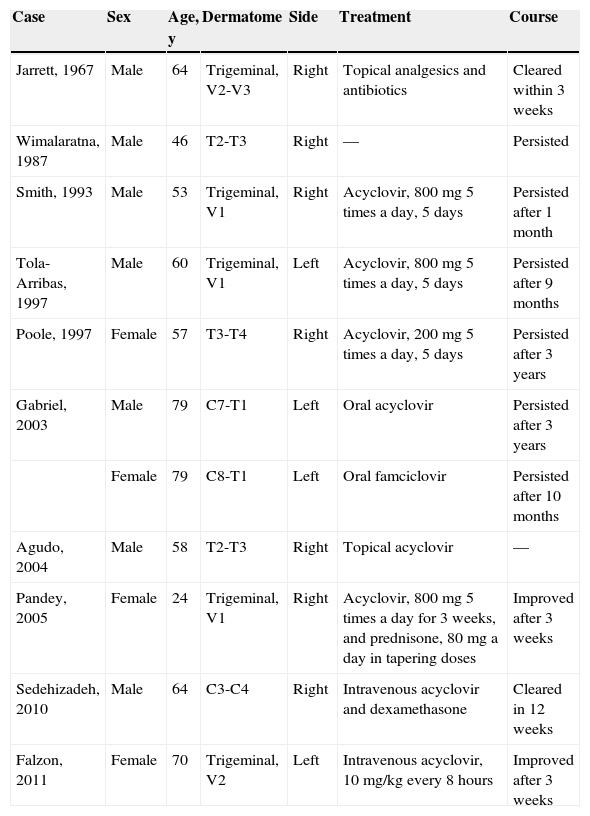

Our search of the literature for herpes zoster associated with Horner syndrome revealed 11 reported cases (Table 1) of patients aged 24 to 79 years, including 7 men and 4 women. Horner syndrome was associated with herpes zoster involvement of branches of the fifth cranial nerve in 5 cases,8 and with involvement of cervical and/or thoracic dermatomes in 6 cases. The right side was involved in 7 cases and the left side in 4. Most patients received antiviral therapy (acyclovir or famciclovir). However, Horner syndrome persisted for weeks or years in 6 cases, while recovery was partial in 2 cases and complete in 2 others.9,10 None of the authors discuss potential factors predicting the persistence of Horner syndrome after herpes zoster resolution. In our view, early antiviral treatment, whether oral or intravenous, reduces the risk of persistence over weeks or years.

Reported Cases of Horner Syndrome Associated with Herpes Zoster.

| Case | Sex | Age, y | Dermatome | Side | Treatment | Course |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jarrett, 1967 | Male | 64 | Trigeminal, V2-V3 | Right | Topical analgesics and antibiotics | Cleared within 3 weeks |

| Wimalaratna, 1987 | Male | 46 | T2-T3 | Right | — | Persisted |

| Smith, 1993 | Male | 53 | Trigeminal, V1 | Right | Acyclovir, 800mg 5 times a day, 5 days | Persisted after 1 month |

| Tola-Arribas, 1997 | Male | 60 | Trigeminal, V1 | Left | Acyclovir, 800mg 5 times a day, 5 days | Persisted after 9 months |

| Poole, 1997 | Female | 57 | T3-T4 | Right | Acyclovir, 200mg 5 times a day, 5 days | Persisted after 3 years |

| Gabriel, 2003 | Male | 79 | C7-T1 | Left | Oral acyclovir | Persisted after 3 years |

| Female | 79 | C8-T1 | Left | Oral famciclovir | Persisted after 10 months | |

| Agudo, 2004 | Male | 58 | T2-T3 | Right | Topical acyclovir | — |

| Pandey, 2005 | Female | 24 | Trigeminal, V1 | Right | Acyclovir, 800mg 5 times a day for 3 weeks, and prednisone, 80mg a day in tapering doses | Improved after 3 weeks |

| Sedehizadeh, 2010 | Male | 64 | C3-C4 | Right | Intravenous acyclovir and dexamethasone | Cleared in 12 weeks |

| Falzon, 2011 | Female | 70 | Trigeminal, V2 | Left | Intravenous acyclovir, 10mg/kg every 8hours | Improved after 3 weeks |

We have reported a new case of Horner syndrome as a rare complication of cervicothoracic herpes zoster. This case is significant in that it underscores the need for dermatologists to examine patients for Horner syndrome and recognize it, in order to initiate early antiviral treatment to prevent other ocular complications and so that neurologists and/or ophthalmologists can be involved in a multidisciplinary management approach.

Please cite this article as: Lobato-Berezo A, Estellés-Pals MT, Gallego-Valdés MÁ, Torres-Perea R. Horner Syndrome: A Rare Complication of Cervical and Thoracic Herpes Zoster Infection. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2015;106:595–597.