Sarcoidosis is a multiorgan disease of unknown etiology, characterized by the presence of noncaseating granulomas. Factors implicated in its etiology include certain microorganisms, such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and a genetic predisposition.1

Our patient was a 31-year-old man from Morocco who had been living in Spain for 11 years. He was seen in dermatology outpatients for evaluation of asymptomatic lesions that had been present on his forehead for 8 months and that he found unsightly. His medical history revealed that he had been on treatment with isoniazid, rifampicin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol for 2 months for low-grade fever and dyspnea, diagnosed as pulmonary tuberculosis. He brought a discharge report from another hospital in the same Autonomous Community in Spain, with details of following additional tests: x-ray study showing a gangliopulmonary pattern, a positive QuantiFERON-TB test, and sputum culture positive for M tuberculosis.

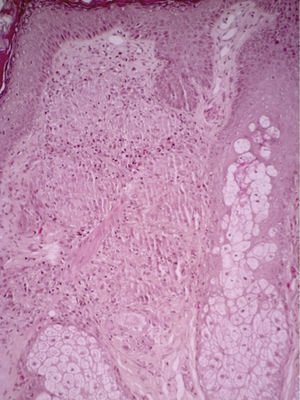

Physical examination revealed an erythematous annular maculopapular rash with central atrophy in the frontal region, in areas in which there were no previous scars (Fig. 1). Histology of a biopsy from 1 of the lesions in the frontal region revealed a granulomatous inflammatory infiltrate formed mainly of a number of Langhans-type giant cells and epithelioid cells (Fig. 2). Given the patient's history of tuberculosis, Ziehl-Neelsen stain and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for mycobacteria were performed on the skin biopsy sample, with a negative result, compatible with cutaneous sarcoidosis. In view of the dermatologic findings and persistence of the patient's dyspnea, transbronchial biopsy was performed. This showed numerous granulomas with no necrosis, but with fibrosis and a discreet peripheral ring of lymphocytes; Ziehl-Neelsen stain was negative. Blood tests revealed an increase in angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) levels to 134U/L (normal range, 8-55U/L) and elevation of uric acid levels to 9.7mg/dL (normal range, 3.5-7.0mg/dL); the other laboratory parameters were normal.

Finally, based on both pathology results, a diagnosis of pulmonary and cutaneous sarcoidosis associated with pulmonary tuberculosis was made. Prednisone, 30mg, was added to the antituberculous treatment and was subsequently tapered to reach a maintenance dose of 5mg; there was a good clinical and radiologic response. The skin lesions resolved, leaving residual scars in the areas of previous central atrophy.

Sarcoidosis and tuberculosis are both granulomatous diseases that rarely occur concomitantly. In contrast to tuberculosis, sarcoidosis is noncaseating.

The most commonly affected organ in sarcoidosis is the lung, followed by skin involvement, which occurs in approximately 24% of cases. Many clinical variants have been described, including papular, plaque, psoriasiform, annular, atrophic, and mixed forms. Long-standing sarcoidosis and lupus pernio lesions typically heal leaving a scar.1 Histologically, the granulomas are formed mainly of epithelioid cells, sometimes with scattered lymphocytes peripherally; Langhans-type multinucleated giant cells may be present; they are more common in longer-standing lesions, though they have also been described in large numbers in early lesions.2

The etiology of sarcoidosis remains unknown, though M tuberculosis has been implicated. Using PCR, Li et al.3 identified DNA from M tuberculosis and from Mycobacterium avium in up to 50% of lung biopsies from patients diagnosed with sarcoidosis. Another study that looked at the etiology and pathogenesis of sarcoidosis was performed by Ding et al.4 Thos authors identified genetic material related to mycobacterial heat shock proteins in 21% of skin biopsies from patients diagnosed with sarcoidosis and concluded that this infection could be a direct etiologic factor.

In clinical practice, there are few reports of patients who have presented the 2 diseases concomitantly or in whom the diagnosis of sarcoidosis was made after that of tuberculosis; these cases are listed in Table 1.5–12 In our review, we have excluded patients who were on corticosteroid treatment for sarcoidosis and who subsequently developed tuberculosis, as the most common cause of the infection in such patients is immunosuppression.

Summary of Published Cases of Sarcoidosis Associated With Tuberculosis.

| Age/Sex | Tuberculosis | Sarcoidosis | Diagnosis of Sarcoidosis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wong et al.5 | 35 y Female | Pulmonary | Lymphatic and pulmonary | Diagnosis of sarcoidosis 15 months after the diagnosis of tuberculosis |

| Mise et al.6 | 43 y Female | Pulmonary | Cutaneous and pulmonary | Concomitant |

| Gupta et al.7 | 65 y Female | Renal | Cutaneous | Diagnosis of sarcoidosis 4 years after the diagnosis of tuberculosis |

| Ahmad et al.8 | 55 y Female | Pulmonary | Cutaneous | Diagnosis of sarcoidosis 3 years after the diagnosis of tuberculosis |

| Ganguly et al.9 | 28 y Male | Pulmonary | Cutaneous | Diagnosis of sarcoidosis 9 months after the diagnosis of tuberculosis |

| Mandal et al.10 | 38 y Female | Miliary | Pulmonary | Concomitant |

| Oluboyo et al.11 | NS Male | Pulmonary | Pulmonary | Concomitant |

| Papaetis et al.12 | 67 y Female | Pulmonary | Pulmonary | Concomitant diagnosis, although the authors state that undiagnosed sarcoidosis had been present for 8 years |

| De la Fuente et al. | 31 y Male | Pulmonary | Cutaneous and pulmonary | Diagnosis of sarcoidosis 3 months after the diagnosis of tuberculosis |

Abbreviation: NS, not specified.

In patients in whom we suspect the concomitant presence of the 2 diseases, it is essential to determine whether the lesions corresponds to one or other granulomatous disease, as skin lesions mimicking sarcoidosis have been reported in patients with tuberculosis, such as the case published by Chokoeva et al.,13 in which the diagnosis of sarcoid-like lesions was only achieved with the aid of the QuantiFERON-TB test and a positive Ziehl Neelsen stain.

Biomarkers that can differentiate between these 2 diseases have been sought. Serum markers related with sarcoidosis, including soluble interleukin-2 receptor (IL-2R), ACE, and Krebs von den Lungen-6 (KL-6), are not sufficiently sensitive or specific to separate these diagnoses. It has recently been observed that the combination of leptin and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 has a sensitivity of 86.5% and a specificity of 73.1% as a marker of sarcoidosis, and this combination could therefore be employed to differentiate the 2 conditions.14

In conclusion, the diagnoses of sarcoidosis and tuberculosis are not mutually exclusive. It is likely that tuberculosis has been a triggering agent of sarcoidosis, although further studies will be necessary to determine its etiologic role. Finally, to prevent the complications of sarcoidosis, corticosteroid treatment should not be delayed.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: de la Fuente-Meira S, Gracia-Cazaña T, Pastushenko I, Ara M. Sarcoidosis y tuberculosis: un desafío diagnóstico. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2016;107:605–607.