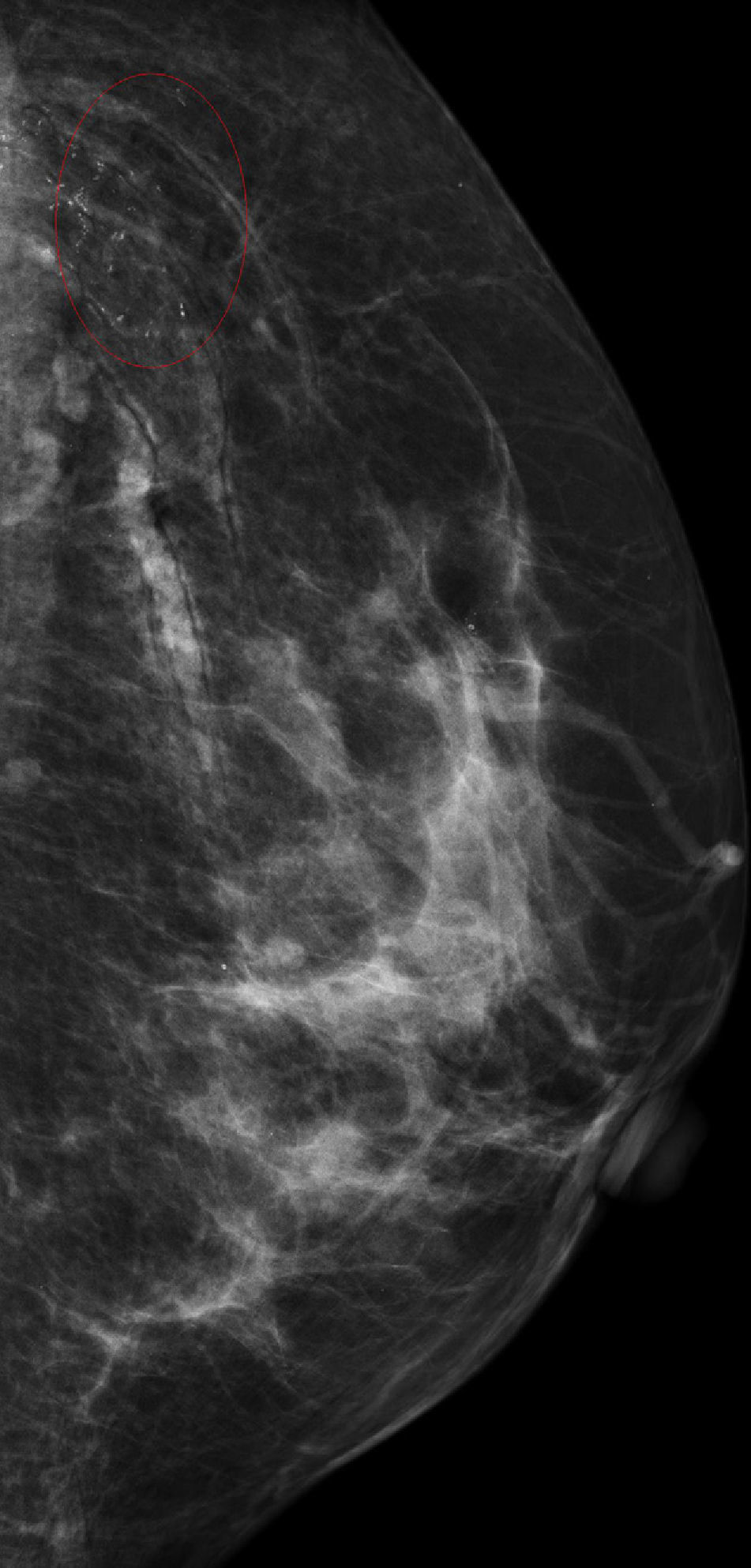

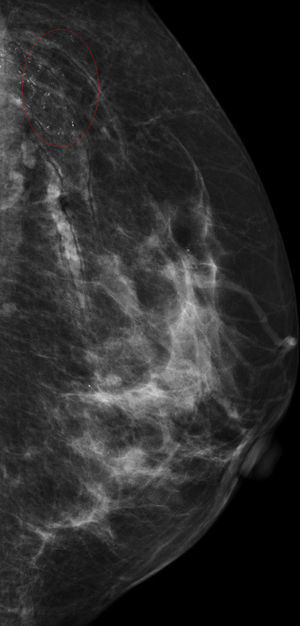

We present the case of a 52-year-old woman with a family history of breast cancer (mother) who came to the hospital for her annual mammography screening. Microcalcifications with a linear distribution following the skin folds were observed, predominantly in the upper outer quadrants of the breasts and in both axillary regions (Fig. 1).

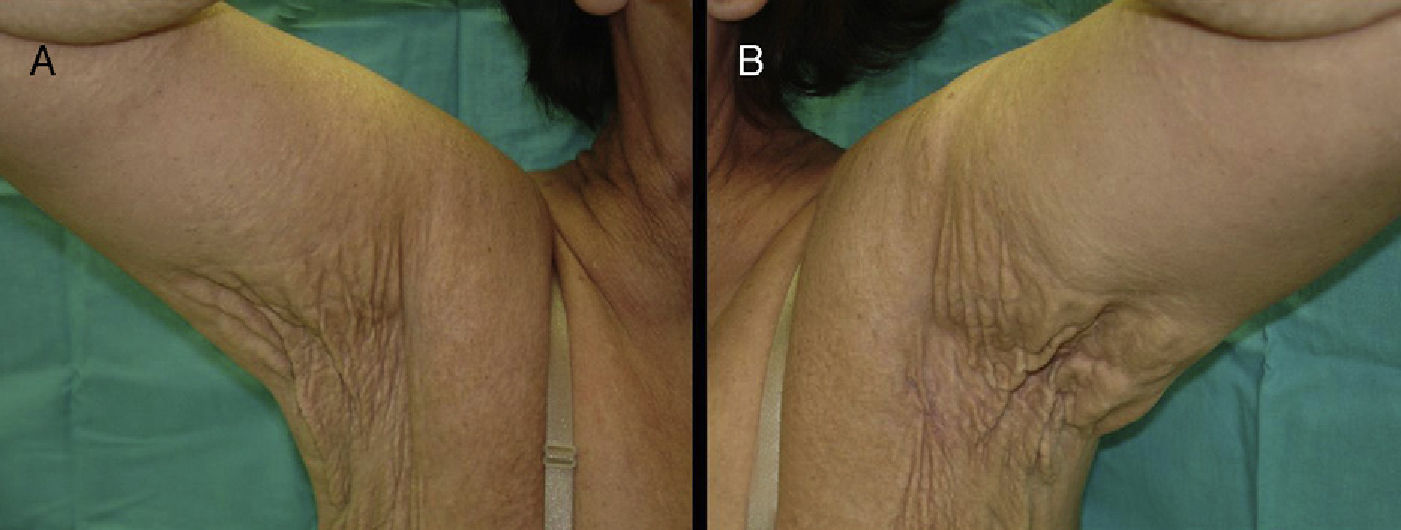

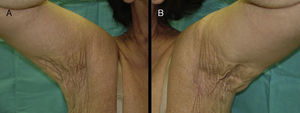

She was referred to the dermatology department for the evaluation of skin changes, which the patient described as having been present for many years. Physical examination revealed conspicuous folds of redundant skin on the neck and in both axillas and groins, with yellow papules on the skin surface giving a “plucked chicken skin” appearance (Fig. 2, A and B). Breast palpation revealed small, superficial, stony-hard nodules, particularly in the upper outer quadrants.

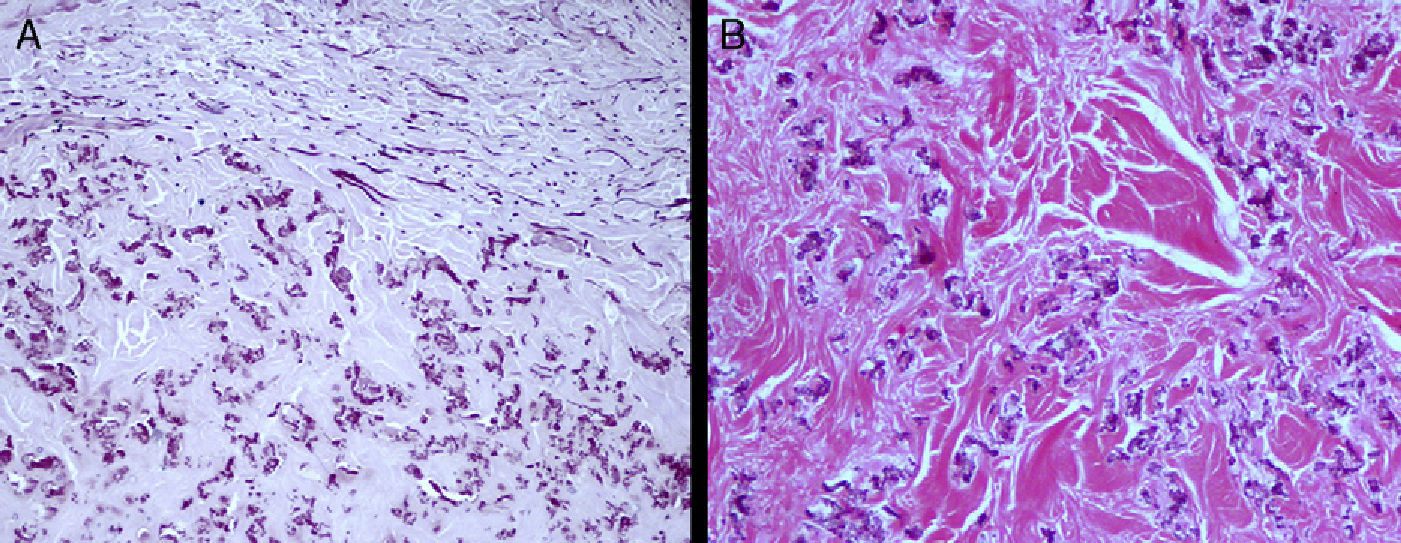

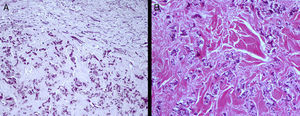

Incisional skin biopsy was performed, attempting to include these nodules. Histology showed fragmentation and calcification of the elastic fibers in the middle and deep thirds of the dermis; these fibers stained blue with hematoxylin-eosin stain due to their high calcium content, and stained a brownish color with von Kossa stain (Fig. 3, A and B).

A diagnosis of pseudoxanthoma elasticum (PXE) was confirmed on the basis of these findings.

On consultation with the ophthalmology, cardiology, and gastroenterology departments, angioid striae were detected in both eyes, with slight edema in the juxtafoveal area of the macula, and mitral valve prolapse; there were no associated digestive tract changes.

PXE is a hereditary connective tissue disease characterized by variable skin, ocular, and cardiovascular manifestations. The inheritance pattern can be autosomal dominant or recessive, although its incidence is twice as high in women as in men. The locus maps to chromosome 16p13.11.2.1,2

The typical skin manifestations consist of the appearance of yellowish macules in the axillas, on the lateral surfaces of the neck, and in the groin. These macules progress to papules that can coalesce to form large plaques and, with the passage of time, the affected skin folds become more lax and more conspicuous. Clinically, the relevant differential diagnosis of these lesions includes xanthoma planum, typically associated with dyslipidemia, actinic elastosis, and the skin lesions observed in patients taking D-penicillamine.3

The most characteristic histological change in the affected organs is the presence of degenerating elastic fibers (fragmentation in the superficial and mid dermis) that become calcified; the absence of such fibers should make us question the diagnosis. The changes in the elastic fibers can be observed after hematoxylin-eosin staining, although von Kossa stain can be useful to better reveal the calcium (Fig. 3B) and Verhoeff-Van Gieson stain for the elastic fibers.4

It is therefore not uncommon to observe images with the density of calcium on plain x-rays or mammography in these patients; these images may have a linear distribution when they are produced by calcification of the elastic fibers in blood vessel walls. There may also be microcalcifications in the breasts and axillas due to calcification of the elastic fibers of the dermis,3 and it has even been suggested that these microcalcifications in the breast could be the result of calcification of the muscle fascia and of the interlobar septa of the gland.5

Microcalcifications on mammography have been reported in numerous diseases, such as Albright osteodystrophy, chronic folliculitis, and osteoma cutis, and in a wide variety of metabolic and endocrine disorders, such as hyperparathyroidism and hypervitaminosis D. The differential diagnosis should also include deposits of metallic substances on the skin due to the use of deodorants and other creams, as these can simulate intracutaneous microcalcifications.5

According to the study by Bercovitch et al.,5 breast microcalcifications may be detected in more than half of women with PXE. In the majority of cases these calcifications are isolated, although they have been reported to form groups in some patients,6 creating calcium-containing masses that would explain the presence of palpable nodules in both axillas, as occurred in our patient. The combination of breast microcalcifications and vascular calcifications is highly characteristic in these patients, and although it is not rare to detect either of these in the normal population, their combined presence should make us look in detail at the skin for the possible presence of changes suggestive of PXE. It has been reported that calcifications affecting vascular structures that contain elastic tissue can be observed on plain radiographs in up to a third of patients5 and calcification of the coronary arteries can give rise to symptoms that simulate those of arteriosclerosis.

In summary, although any calcification observed on mammography should be an alarm signal, it is important to know the frequency of association of mammographic microcalcifications with PXE and to take this into account in the differential diagnosis of breast cancer.7,8

Please cite this article as: Padilla-España L, Fernández-Morano T, Del Boz J, Fúnez R. Seudoxantoma elástico en el diagnóstico diferencial de las calcificaciones axilares en la mamografía. Actas Dermosifiliogr.2012;103:647-649.