A 61-year-old woman with no history of allergy to drugs or addictions consulted us for evaluation of facial lesions present for many years. She reported no relevant family history but her own history included renal angiomyolipomas and severe acne continuing after adolescence. She had also been diagnosed with rosacea some years before and was following treatments with topical metronidazole and brimonidine. She complained of flushing and papular and pustular skin eruptions on the face that had resolved before the visit but had left her with other persistent papules.

Physical examinationWe observed malar erythema, telangiectasia and a dozen hemispherical, indurated, whitish-yellow papules measuring 2–3mm in diameter dispersed across the forehead, chin, and cheeks (Fig. 1).

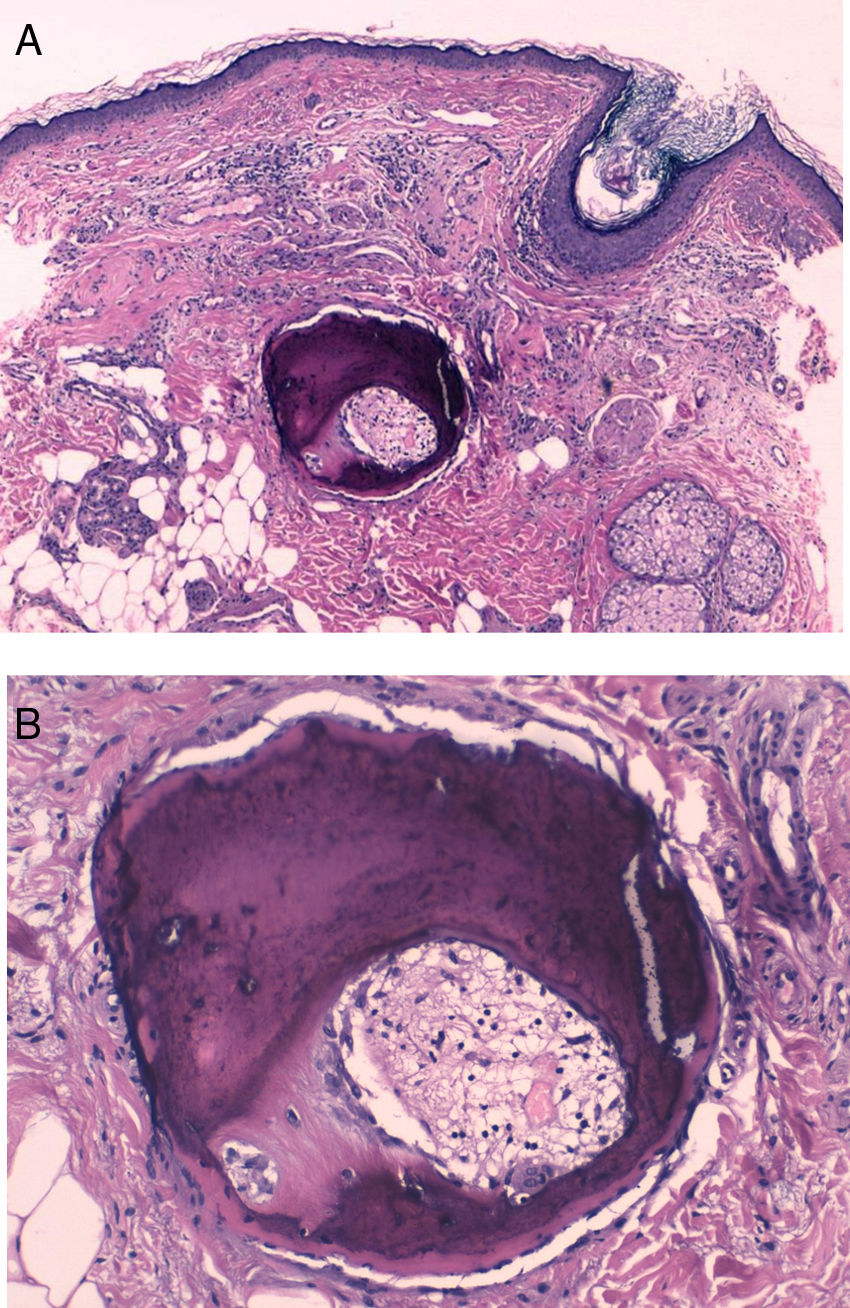

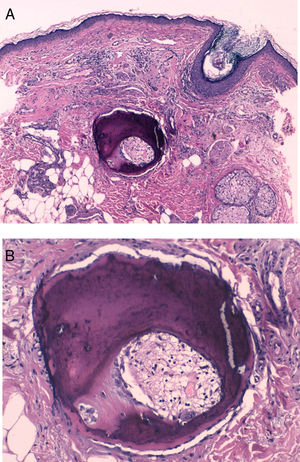

HistopathologyA well-defined, dark bluish-violet nodular deposit was observed in the mid-dermis (Fig. 2A). Higher magnification revealed mature bony trabeculae with osteocytes inside and Haversian canals containing blood vessels and connective tissue (Fig. 2B).

Additional TestsA blood work-up showed no abnormalities in renal function. Calcium and phosphorous metabolism was normal.

What Is Your Diagnosis?DiagnosisMultiple miliary osteoma cutis (MMOC) secondary to acne.

Clinical Course and TreatmentThe lesions have remained stable. The patient opted not to undergo treatment.

CommentMMOC is a rare subtype of skin ossification that is characterized by bony tissue formation in the dermis and subcutaneous layers. The pathogenesis is unclear, but an association with chronic inflammatory processes such as acne, as described in our patient, has been suggested.1 Chronic inflammation is thought to induce metaplasia in pluripotent dermal mesenchymal cells and lead to the formation of osteoblasts.2 Previous authors have described a possible association between MMOC and treatment with bisphosphonates.1

MMOC is characterized clinically by the presence of multiple, firm, asymptomatic, skin-colored papules and nodules mainly on the face in young or postmenopausal women.1–3Clinical signs and imaging (dermatologic ultrasound and simple radiographs) can facilitate diagnosis, but histology is required for certainty. Histology demonstrates bony spicules in the dermis and osteocytes and osteoblasts in subcutaneous cellular tissue.2

Differential diagnosis must take into consideration cutaneous calcification, which is associated with endocrine and metabolic disorders. In this condition calcium is deposited in the dermis, whereas in MMOC bone is actually formed.4 The absence of other clinical signs, the age at which the disorder presents, and the clinical course can also help distinguish MMOC from primary syndromes associated with cutaneous osteomas, such as Albright hereditary osteodystrophy, progressive ossifying fibrodysplasia, progressive osseous heteroplasia, and platelike osteoma cutis. Finally, differential diagnosis should also consider closed comedones and milium cysts.5

No standard treatment for MMOC has emerged. Any approach undertaken will have aesthetic improvement as its purpose. Topical retinoids, carbon dioxide laser therapy,2 dermabrasion, and the excision of large lesions have been tried, with variable results.1,4 Surgical mini-excision using a needle and curettage was reported to give good results in a series of 11 patients.1

This description of a case of MMOC — an uncommon, benign condition that is probably underdiagnosed — shows that details of a patient's medical history can provide the clues to making this diagnosis. Our patient had experienced severe acne, a disease that other published cases have linked to the development of MMOC.1,6

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: González-Cruz C, Calderón VC, Briones VG-P. Pápulas faciales induradas. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2019;110:599–600.