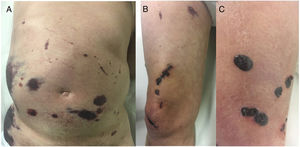

A 67-year-old man who had been diagnosed 1 year earlier with inoperable glioblastoma multiforme that was refractory to multiple treatments was treated with low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) after an episode of pulmonary thromboembolism and deep venous thrombosis. Disseminated asymptomatic skin lesions appeared 5 days after beginning LMWH therapy. Despite the spectacular appearance of the skin lesions the patient’s general condition was excellent. Fever and other clinical signs of infection were absent. Physical examination revealed large, noninfiltrated ecchymotic plaques located mainly on the abdomen without underlying fluid collection (Fig. 1A), necrotic lesions on the right thigh (Fig. 1B), and tense blisters with hemorrhagic content in the distal area of the right leg (Fig. 1C).

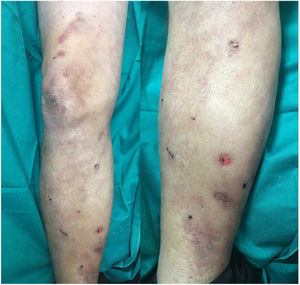

Based on the patient’s clinical picture a suspected diagnosis of heparin-induced skin necrosis was established. Laboratory tests, including a complete blood count and coagulation parameters, revealed no findings of interest, apart from thrombocytopenia (107000 platelets/mL). Tests for anti-platelet factor 4 antibodies were negative. Heparin treatment was immediately discontinued and oral anticoagulation treatment with warfarin was initiated. Fifteen days after heparin discontinuation a clear improvement in the patient’s lesions was observed (Fig. 2) and the platelet count returned to 130000 platelets/mL. Skin necrosis in response to anticoagulant treatment is a rare adverse reaction, and is rarer in patients treated with heparin than in those treated with oral anticoagulants (0.01% of patients).1 Although the pathogenesis of this adverse effect is unclear, most authors suspect an immune mechanism whereby heparin-induced production of anti-platelet antibodies triggers platelet aggregation and consequent vascular occlusion. Heparin-induced skin necrosis is considered part of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia syndrome, although a decrease in platelet count is observed in only 50% of patients.2 Clinical signs appear between 5 and 15 days after beginning treatment, usually close to the injection site, although rarer cases involving lesions at a distance from the injection site have also been described.3

Lesions initially appear as painful, well-delimited erythematous or hemorrhagic macules that become indurated over the following days. Subsequently, the lesions become necrotic and give way to tense, painful serosanguineous sores and blisters that evolve into marked necrosis of the skin and subcutaneous cellular tissue. In addition to marked necrotic lesions, affected patients may present with other abortive erythematous or cyanotic lesions.

Blood tests typically reveal thrombocytopenia and the presence of anti-platelet factor IV antibodies, although their absence is insufficient to rule out heparin-induced skin necrosis.4

Diagnosis is mainly clinical, with histological confirmation in doubtful cases. The main differential diagnoses are warfarin-induced skin necrosis and heparin-induced type-IV hypersensitivity reaction.

Treatment consists of immediate discontinuation of heparin administration and replacement with other anticoagulants such as direct thrombin inhibitors (hirudins) or warfarin.5,6 Substitution with other LMWHs is not recommended. Discontinuation of heparin treatment is followed by rapid recovery of the platelet count and progressive healing of necrotic lesions, as occurred in the present case.

The most common adverse effects of heparin include bleeding, alopecia (in up to 50% of patients undergoing prolonged treatment), osteoporosis, hypersensitivity phenomena, and thrombocytopenia. Skin necrosis is a rare adverse reaction to heparin, but should be taken into consideration.7 Diagnosis is primarily clinical, and early withdrawal of heparin treatment is essential to avoid the development of potentially fatal visceral thrombotic complications.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Estébanez A, Silva E, Cordero P, Martín JM. Necrosis cutánea por heparina con afectación a distancia del punto de administración. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2019;110:869–871.