Knowledge of seasonal variation of cutaneous disorder may be useful for heath planning and disease management. To date, however, descriptions of seasonality including all diagnoses in a representative country sample are very scarce.

ObjectivesTo evaluate if clinical dermatologic diagnosis in Spain change in the hot vs cold periods.

Materials and methodsSurvey based on a random sample of dermatologists in Spain, stratified by area. Each participant collected data during 6 days of clinical activity in 2016 (3 in the cold period of the year, 3 in the hot period). Clinical diagnoses were coded using ICD-10.

ResultsWith a 62% response proportion, we got data on 10999 clinical diagnoses. ICD-10 diagnostic groups that showed changes were: other benign neoplasms of skin (D23), rosacea (L71) and other follicular disorders (L73), which were more common in the hot period and acne (L70) which was more frequent in the cold period. We describe differences in the paediatric population and in private vs public practice. Some of these differences might be associated to differences in the population demanding consultations in different periods.

ConclusionsThe frequency of most clinical diagnosis made by dermatologists does not change over the year. Just a few of the clinical diagnoses made by dermatologists show a variation in hot vs cold periods. These variations could be due to the diseases themselves or to seasonal changes in the demand for consultation.

El conocimiento de las variaciones de las enfermedades dermatológicas a lo largo del año podría ser útil para la planificación en salud y el manejo de las enfermedades. Sin embargo, existe escasa información acerca de la variación de los diagnósticos dermatológicos en diferentes épocas del año en una muestra nacional representativa.

ObjetivosEvaluar si existe variación en los diagnósticos clínicos dermatológicos entre la temporada de frío y calor en España.

Material y métodosLos datos se han obtenido mediante una encuesta anónima realizada a una muestra aleatoria y representativa de dermatólogos españoles estratificados por área. Cada uno de los participantes recogió todos los diagnósticos clínicos durante 6 días de consulta en 2016 (3 en la temporada de frío y 3 en la temporada de calor). Los diagnósticos se codificaron según la CIE-10.

ResultadosCon una proporción de respuesta de 62%, se recolectaron 11.223 diagnósticos clínicos. Los grupos diagnóstico CIE-10 que mostraron variaciones entre temporadas fueron: otras neoplasias benignas de la piel (D23), rosácea (L71) y otros trastornos foliculares (L73), los cuales fueron más frecuentes en la temporada de calor, y acné (L70) el cual fue más frecuente en la temporada de frío. Además, describimos las diferencias en la población pediátrica y según el tipo de asistencia pública frente a privada. Algunas de estas diferencias podrían estar relacionadas con diferencias en la población que consulta en las distintas temporadas.

ConclusionesLa frecuencia de la mayoría de los diagnósticos clínicos realizados por dermatólogos no sufre variaciones a lo largo del año. Solo algunos de los diagnósticos clínicos muestran variaciones entre la temporada de frío frente a calor. Estas variaciones observadas pueden estar en relación con las propias enfermedades o pueden ser debidas a cambios estacionales en la demanda de consultas dermatológicas.

Seasonal variation in several dermatologic diseases has been previously described. This variation has been mostly attributed to environmental factors and its impact on skin disorders..1,2 Examples of this phenomenon are perniosis (chilblains), which is more common in winter and spring2,3; hand, foot, and mouth disease, more common in summer and autumn2 and Groveŕs disease which is more common in winter.4 Observations on the seasonality of skin disorders have been reported in isolated diseases, and using data from dermatopathology archives and non-representative small surveys.2,4–8 The only description of the seasonality in a representative country sample was done in the USA, using data from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey 1990-1998.1

Knowledge of seasonal variation of cutaneous disorder may be useful for heath planning and disease management. To date, however, descriptions of seasonality including all clinical diagnoses in a representative country sample are very scarce.

The objective of the present study was to evaluate whether seasonal variation in dermatologic diagnosis in Spain exists and factors associated with seasonality. The study data were derived from the DIADERM national sample9

Materials and methodsData for this study were compiled from an anonymous national randomized survey among a representative sample of Spanish dermatologist belonging to the Spanish Academy of Dermatology and Venereology9 (AEDV). The study was coordinated by the Spanish Group of Epidemiology and Health Promotion from the AEDV in collaboration with the Research Unit of the AEDV.

Sample selection: The sample of dermatologists was obtained from the AEDV Dermatologists membership list, which were selected using randomized sampling, stratified for the different geographical sections of the AEDV. More than 98% of the Spanish dermatologists belong to the AEDV.

Each participant collected data during 6 days of clinical activity in 2016 (January 19, 20 and 21 and May 18, 19 and 20).

The sample size was calculated to get a±2/1000 precision for diagnosis in 5/1000 proportions. After assuming a design effect of 2, the number of dermatologist needed for the study were 70. Assuming a response rate of 60% and after adjustment for geographical sections, the number of Dermatologist asked for participation were 124.

Data included in the survey were: clinical dermatologic diagnosis, whether the patient was under age 18 or not, whether it was a presential or a teledermatology consultation, reason for consultation and secondary diagnosis. Other variables were: public or private institution, the origin of the patient (direct access, primary care physician, other specialist or revision) and his destination (discharge, follow-up with the dermatologist or follow-up with another specialist). Personal data and information about therapy were not recorded.

The coding of the different clinical diagnosis was carried out by an expert dermatologist using the 10th version of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10). When coding was doubtful a revision was carried out by three Dermatologists with special interest in diagnosis coding from de E-Dermatology and Image group of the AEDV. A quality control of the coding included a review of a random sample of the data and showed 0.16% of errors.

We had data from January (winter) and May (late spring).2 The weather conditions during the period of the study were as follows: In January 2016 the average daytime temperature was 9.5°C and the average monthly precipitation was 90mm; in May 2016 the average daytime temperature was 16.4°C and the average monthly precipitation was 78mm (data collected from the Spanish Agency of Meteorology (AEMET)).

Statistical analysis: a descriptive analysis was performed considering the sampling method. Continuous variables were expressed as means with standard deviations in symmetric distributions. Categorical variables were expressed as total numbers with percentages. Characteristics in both seasons were compared using either chi-square test or Student's t-test. In addition, crude and adjusted Odds Ratios (OR) with 95% Confidence Intervals (95%CI) were obtained by means of a multilevel model nested in geographical areas, to check if seasonal differences are related to the different demographic characteristics of the sample in each season.

Multivariate models were obtained by means of a backward selection strategy and likelihood ratio test comparisons. Factors used were the variables included in the survey.

The statistical analysis was performed with Stata (version 14.1 Statacorp, Texas, USA). The study protocol was approved by the ethical committee of Granada.

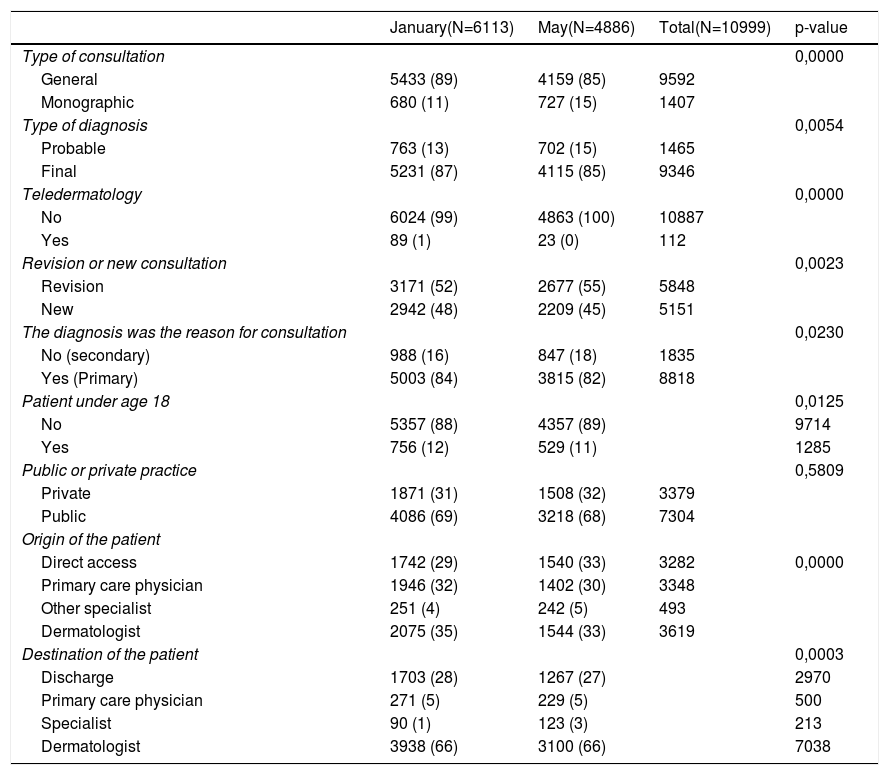

ResultsAmong the dermatologists selected, 65% (80/124) sent their results in the cold period of the survey and 59% (73/124) in the hot period. A total of 10.999 clinical diagnoses were made in 8953 patients. Table 1 describes the characteristics of the consultations included in each study period. Due to the large numbers, many of the differences are statistically significant, but they are small.

Overall description of activity in each period.

| January(N=6113) | May(N=4886) | Total(N=10999) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of consultation | 0,0000 | |||

| General | 5433 (89) | 4159 (85) | 9592 | |

| Monographic | 680 (11) | 727 (15) | 1407 | |

| Type of diagnosis | 0,0054 | |||

| Probable | 763 (13) | 702 (15) | 1465 | |

| Final | 5231 (87) | 4115 (85) | 9346 | |

| Teledermatology | 0,0000 | |||

| No | 6024 (99) | 4863 (100) | 10887 | |

| Yes | 89 (1) | 23 (0) | 112 | |

| Revision or new consultation | 0,0023 | |||

| Revision | 3171 (52) | 2677 (55) | 5848 | |

| New | 2942 (48) | 2209 (45) | 5151 | |

| The diagnosis was the reason for consultation | 0,0230 | |||

| No (secondary) | 988 (16) | 847 (18) | 1835 | |

| Yes (Primary) | 5003 (84) | 3815 (82) | 8818 | |

| Patient under age 18 | 0,0125 | |||

| No | 5357 (88) | 4357 (89) | 9714 | |

| Yes | 756 (12) | 529 (11) | 1285 | |

| Public or private practice | 0,5809 | |||

| Private | 1871 (31) | 1508 (32) | 3379 | |

| Public | 4086 (69) | 3218 (68) | 7304 | |

| Origin of the patient | ||||

| Direct access | 1742 (29) | 1540 (33) | 3282 | 0,0000 |

| Primary care physician | 1946 (32) | 1402 (30) | 3348 | |

| Other specialist | 251 (4) | 242 (5) | 493 | |

| Dermatologist | 2075 (35) | 1544 (33) | 3619 | |

| Destination of the patient | 0,0003 | |||

| Discharge | 1703 (28) | 1267 (27) | 2970 | |

| Primary care physician | 271 (5) | 229 (5) | 500 | |

| Specialist | 90 (1) | 123 (3) | 213 | |

| Dermatologist | 3938 (66) | 3100 (66) | 7038 |

Data use diagnoses as the unit of analysis and are expressed as absolute number and percentages (%).

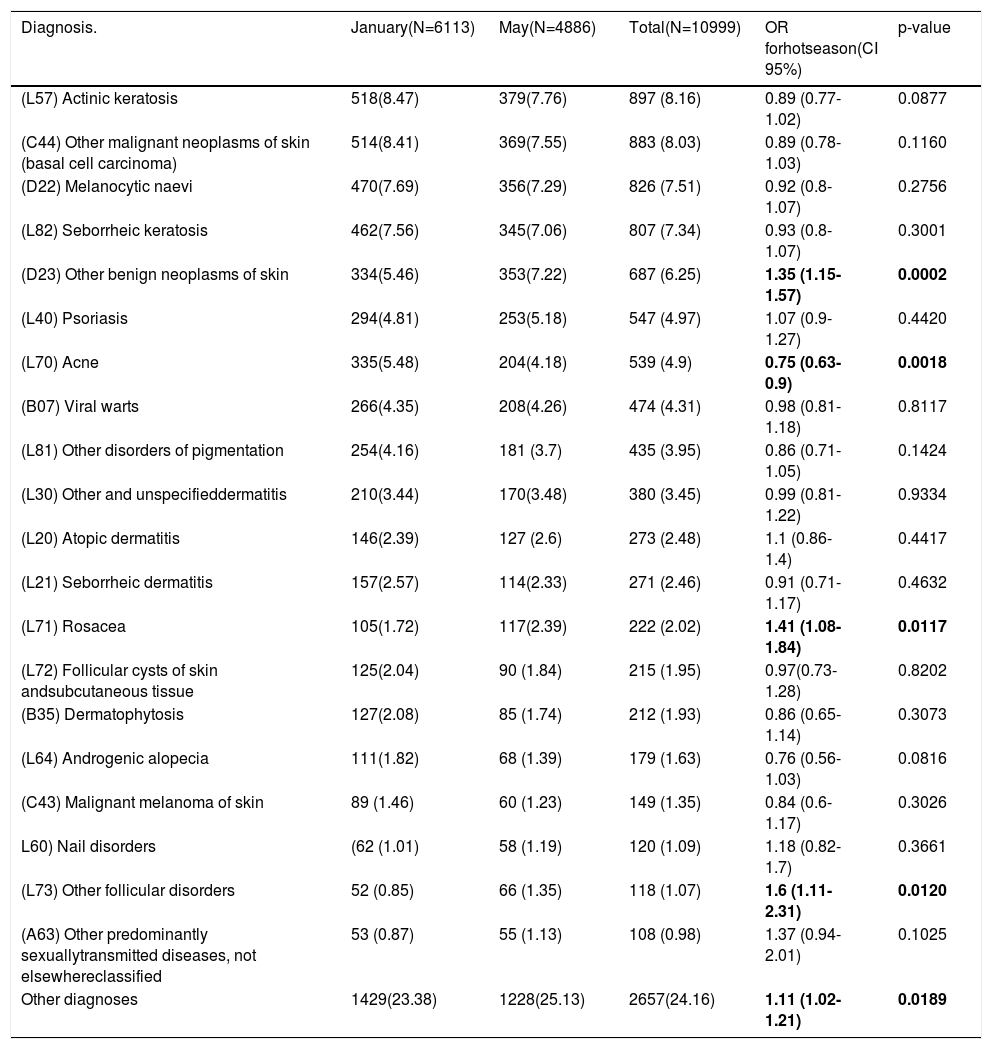

Frequency of dermatologic diagnosis in the different periods: As shown in Table 2 the three most frequent dermatologic clinical diagnosis were the same in both periods; actinic keratosis (L57), other malignant neoplasms of skin (basal cell carcinoma) (C44) and melanocytic naevi (D22). According to crude OR, the only diagnostic groups that showed seasonal changes were: other benign neoplasms of skin (D23), rosacea (L71) and other follicular disorders (L73), more common in the hot season and acne (L70) which was more common in the cold season.

Most frequent dermatologic diagnosis in the study in each period.

| Diagnosis. | January(N=6113) | May(N=4886) | Total(N=10999) | OR forhotseason(CI 95%) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (L57) Actinic keratosis | 518(8.47) | 379(7.76) | 897 (8.16) | 0.89 (0.77-1.02) | 0.0877 |

| (C44) Other malignant neoplasms of skin (basal cell carcinoma) | 514(8.41) | 369(7.55) | 883 (8.03) | 0.89 (0.78-1.03) | 0.1160 |

| (D22) Melanocytic naevi | 470(7.69) | 356(7.29) | 826 (7.51) | 0.92 (0.8-1.07) | 0.2756 |

| (L82) Seborrheic keratosis | 462(7.56) | 345(7.06) | 807 (7.34) | 0.93 (0.8-1.07) | 0.3001 |

| (D23) Other benign neoplasms of skin | 334(5.46) | 353(7.22) | 687 (6.25) | 1.35 (1.15-1.57) | 0.0002 |

| (L40) Psoriasis | 294(4.81) | 253(5.18) | 547 (4.97) | 1.07 (0.9-1.27) | 0.4420 |

| (L70) Acne | 335(5.48) | 204(4.18) | 539 (4.9) | 0.75 (0.63-0.9) | 0.0018 |

| (B07) Viral warts | 266(4.35) | 208(4.26) | 474 (4.31) | 0.98 (0.81-1.18) | 0.8117 |

| (L81) Other disorders of pigmentation | 254(4.16) | 181 (3.7) | 435 (3.95) | 0.86 (0.71-1.05) | 0.1424 |

| (L30) Other and unspecifieddermatitis | 210(3.44) | 170(3.48) | 380 (3.45) | 0.99 (0.81-1.22) | 0.9334 |

| (L20) Atopic dermatitis | 146(2.39) | 127 (2.6) | 273 (2.48) | 1.1 (0.86-1.4) | 0.4417 |

| (L21) Seborrheic dermatitis | 157(2.57) | 114(2.33) | 271 (2.46) | 0.91 (0.71-1.17) | 0.4632 |

| (L71) Rosacea | 105(1.72) | 117(2.39) | 222 (2.02) | 1.41 (1.08-1.84) | 0.0117 |

| (L72) Follicular cysts of skin andsubcutaneous tissue | 125(2.04) | 90 (1.84) | 215 (1.95) | 0.97(0.73-1.28) | 0.8202 |

| (B35) Dermatophytosis | 127(2.08) | 85 (1.74) | 212 (1.93) | 0.86 (0.65-1.14) | 0.3073 |

| (L64) Androgenic alopecia | 111(1.82) | 68 (1.39) | 179 (1.63) | 0.76 (0.56-1.03) | 0.0816 |

| (C43) Malignant melanoma of skin | 89 (1.46) | 60 (1.23) | 149 (1.35) | 0.84 (0.6-1.17) | 0.3026 |

| L60) Nail disorders | (62 (1.01) | 58 (1.19) | 120 (1.09) | 1.18 (0.82- 1.7) | 0.3661 |

| (L73) Other follicular disorders | 52 (0.85) | 66 (1.35) | 118 (1.07) | 1.6 (1.11-2.31) | 0.0120 |

| (A63) Other predominantly sexuallytransmitted diseases, not elsewhereclassified | 53 (0.87) | 55 (1.13) | 108 (0.98) | 1.37 (0.94-2.01) | 0.1025 |

| Other diagnoses | 1429(23.38) | 1228(25.13) | 2657(24.16) | 1.11 (1.02-1.21) | 0.0189 |

Data are expressed as absolute number and percentages (%). OR: Odds Ratio; CI: 95%

Confidence Interval. Statistically significant differences marked in bold.

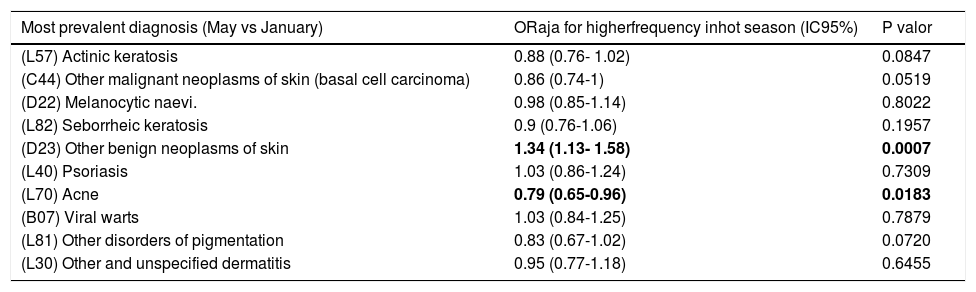

Table 3 compares the frequency of clinical diagnosis in each season, after excluding the effect of differences in sample characteristics (type of consultation, type of diagnosis, patient age group, teledermatology, revision or new consultation, etc.) as potential confounding factors. Table 3 shows a statistically significant seasonal association for other benign neoplasms of skin (D23), being more prevalent in the hot season of the study. On the contrary, acne(L70) seems more prevalent in the cold season of the study.

Adjusted model for seasonal variation.

| Most prevalent diagnosis (May vs January) | ORaja for higherfrequency inhot season (IC95%) | P valor |

|---|---|---|

| (L57) Actinic keratosis | 0.88 (0.76- 1.02) | 0.0847 |

| (C44) Other malignant neoplasms of skin (basal cell carcinoma) | 0.86 (0.74-1) | 0.0519 |

| (D22) Melanocytic naevi. | 0.98 (0.85-1.14) | 0.8022 |

| (L82) Seborrheic keratosis | 0.9 (0.76-1.06) | 0.1957 |

| (D23) Other benign neoplasms of skin | 1.34 (1.13- 1.58) | 0.0007 |

| (L40) Psoriasis | 1.03 (0.86-1.24) | 0.7309 |

| (L70) Acne | 0.79 (0.65-0.96) | 0.0183 |

| (B07) Viral warts | 1.03 (0.84-1.25) | 0.7879 |

| (L81) Other disorders of pigmentation | 0.83 (0.67-1.02) | 0.0720 |

| (L30) Other and unspecified dermatitis | 0.95 (0.77-1.18) | 0.6455 |

a Odds Ratios adjusted for data included in the survey. Statistically significant differences marked in bold.

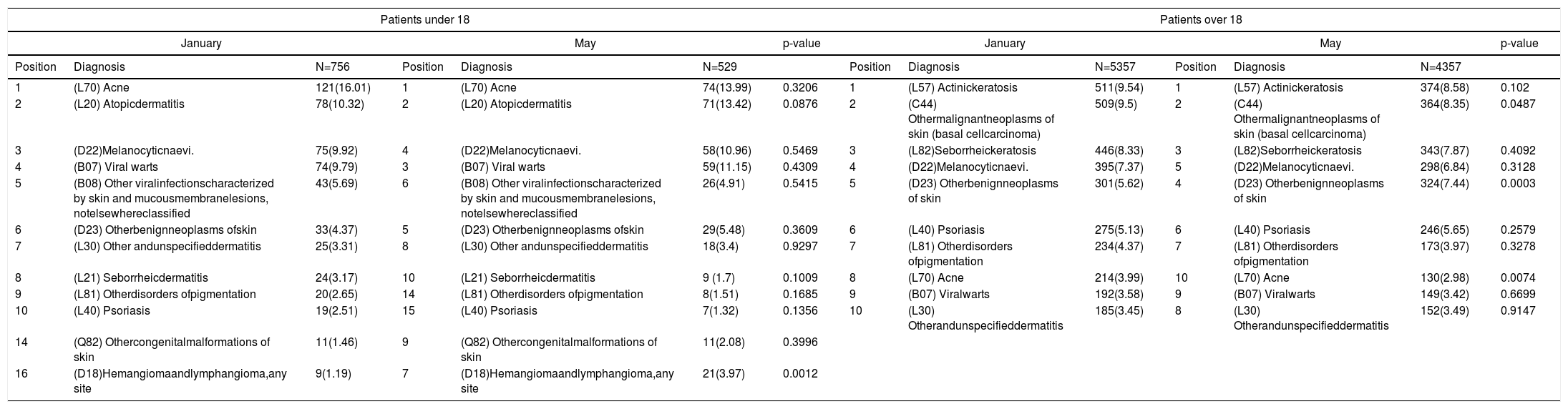

Age-group subanalysis: For patients aged under 18 we found statistically significant seasonal association for hemangioma and lymphangioma, any site(D18), more prevalent in the hot season of the study. Among those over 18 we found a statistically significant seasonal association for other benign neoplasms of skin (D23) more prevalent in May and acne (L70) more prevalent in January (Table 4).

Most frequent dermatologic diagnosis in the study by age-group and time of the year.

| Patients under 18 | Patients over 18 | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| January | May | p-value | January | May | p-value | ||||||||

| Position | Diagnosis | N=756 | Position | Diagnosis | N=529 | Position | Diagnosis | N=5357 | Position | Diagnosis | N=4357 | ||

| 1 | (L70) Acne | 121(16.01) | 1 | (L70) Acne | 74(13.99) | 0.3206 | 1 | (L57) Actinickeratosis | 511(9.54) | 1 | (L57) Actinickeratosis | 374(8.58) | 0.102 |

| 2 | (L20) Atopicdermatitis | 78(10.32) | 2 | (L20) Atopicdermatitis | 71(13.42) | 0.0876 | 2 | (C44) Othermalignantneoplasms of skin (basal cellcarcinoma) | 509(9.5) | 2 | (C44) Othermalignantneoplasms of skin (basal cellcarcinoma) | 364(8.35) | 0.0487 |

| 3 | (D22)Melanocyticnaevi. | 75(9.92) | 4 | (D22)Melanocyticnaevi. | 58(10.96) | 0.5469 | 3 | (L82)Seborrheickeratosis | 446(8.33) | 3 | (L82)Seborrheickeratosis | 343(7.87) | 0.4092 |

| 4 | (B07) Viral warts | 74(9.79) | 3 | (B07) Viral warts | 59(11.15) | 0.4309 | 4 | (D22)Melanocyticnaevi. | 395(7.37) | 5 | (D22)Melanocyticnaevi. | 298(6.84) | 0.3128 |

| 5 | (B08) Other viralinfectionscharacterized by skin and mucousmembranelesions, notelsewhereclassified | 43(5.69) | 6 | (B08) Other viralinfectionscharacterized by skin and mucousmembranelesions, notelsewhereclassified | 26(4.91) | 0.5415 | 5 | (D23) Otherbenignneoplasms of skin | 301(5.62) | 4 | (D23) Otherbenignneoplasms of skin | 324(7.44) | 0.0003 |

| 6 | (D23) Otherbenignneoplasms ofskin | 33(4.37) | 5 | (D23) Otherbenignneoplasms ofskin | 29(5.48) | 0.3609 | 6 | (L40) Psoriasis | 275(5.13) | 6 | (L40) Psoriasis | 246(5.65) | 0.2579 |

| 7 | (L30) Other andunspecifieddermatitis | 25(3.31) | 8 | (L30) Other andunspecifieddermatitis | 18(3.4) | 0.9297 | 7 | (L81) Otherdisorders ofpigmentation | 234(4.37) | 7 | (L81) Otherdisorders ofpigmentation | 173(3.97) | 0.3278 |

| 8 | (L21) Seborrheicdermatitis | 24(3.17) | 10 | (L21) Seborrheicdermatitis | 9 (1.7) | 0.1009 | 8 | (L70) Acne | 214(3.99) | 10 | (L70) Acne | 130(2.98) | 0.0074 |

| 9 | (L81) Otherdisorders ofpigmentation | 20(2.65) | 14 | (L81) Otherdisorders ofpigmentation | 8(1.51) | 0.1685 | 9 | (B07) Viralwarts | 192(3.58) | 9 | (B07) Viralwarts | 149(3.42) | 0.6699 |

| 10 | (L40) Psoriasis | 19(2.51) | 15 | (L40) Psoriasis | 7(1.32) | 0.1356 | 10 | (L30) Otherandunspecifieddermatitis | 185(3.45) | 8 | (L30) Otherandunspecifieddermatitis | 152(3.49) | 0.9147 |

| 14 | (Q82) Othercongenitalmalformations of skin | 11(1.46) | 9 | (Q82) Othercongenitalmalformations of skin | 11(2.08) | 0.3996 | |||||||

| 16 | (D18)Hemangiomaandlymphangioma,any site | 9(1.19) | 7 | (D18)Hemangiomaandlymphangioma,any site | 21(3.97) | 0.0012 | |||||||

Data are expressed as absolute number and percentages (%).

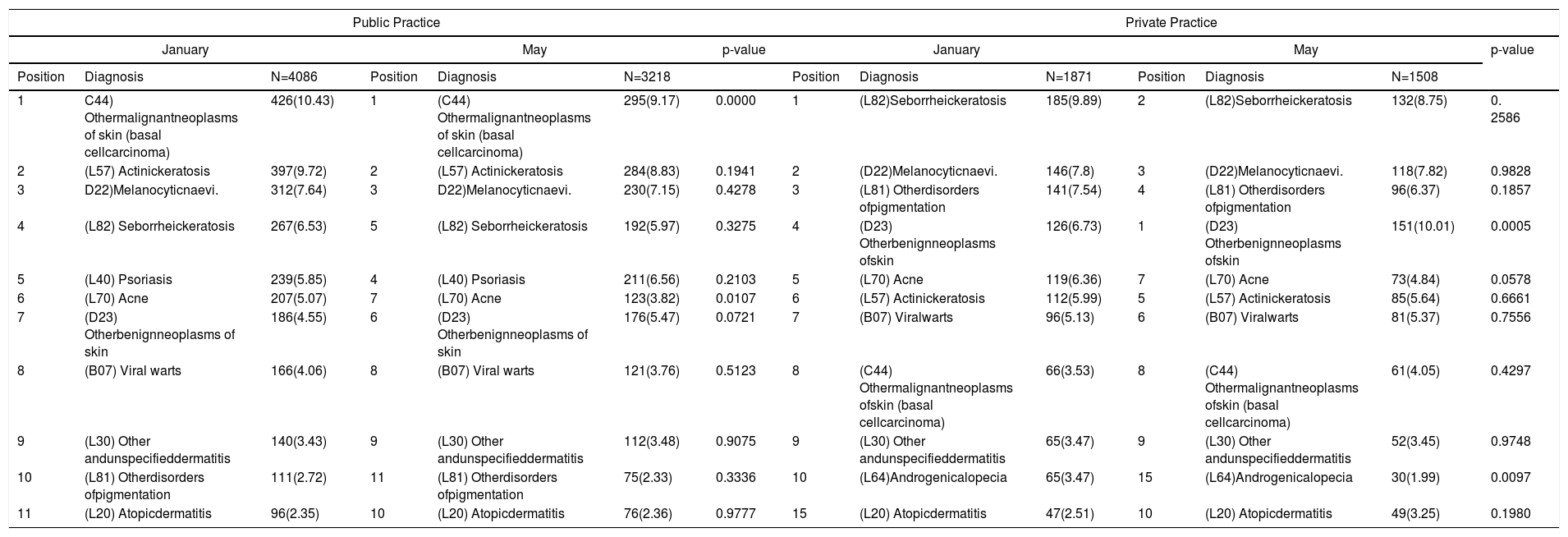

Public or private practice subanalysis: In the public practice we found statistically significant seasonal association for acne (L70) and other malignant neoplasms of skin (basal cell carcinoma) (C44) more prevalent in January. In private practice we found a statistically significant seasonal association for other benign neoplasms of skin (D23) more prevalent in May and acne (L70) more prevalent in January (Table 5).

Prevalence of dermatologic diagnosis in the private practice in the different periods of the study.

| Public Practice | Private Practice | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| January | May | p-value | January | May | p-value | ||||||||

| Position | Diagnosis | N=4086 | Position | Diagnosis | N=3218 | Position | Diagnosis | N=1871 | Position | Diagnosis | N=1508 | ||

| 1 | C44) Othermalignantneoplasms of skin (basal cellcarcinoma) | 426(10.43) | 1 | (C44) Othermalignantneoplasms of skin (basal cellcarcinoma) | 295(9.17) | 0.0000 | 1 | (L82)Seborrheickeratosis | 185(9.89) | 2 | (L82)Seborrheickeratosis | 132(8.75) | 0. 2586 |

| 2 | (L57) Actinickeratosis | 397(9.72) | 2 | (L57) Actinickeratosis | 284(8.83) | 0.1941 | 2 | (D22)Melanocyticnaevi. | 146(7.8) | 3 | (D22)Melanocyticnaevi. | 118(7.82) | 0.9828 |

| 3 | D22)Melanocyticnaevi. | 312(7.64) | 3 | D22)Melanocyticnaevi. | 230(7.15) | 0.4278 | 3 | (L81) Otherdisorders ofpigmentation | 141(7.54) | 4 | (L81) Otherdisorders ofpigmentation | 96(6.37) | 0.1857 |

| 4 | (L82) Seborrheickeratosis | 267(6.53) | 5 | (L82) Seborrheickeratosis | 192(5.97) | 0.3275 | 4 | (D23) Otherbenignneoplasms ofskin | 126(6.73) | 1 | (D23) Otherbenignneoplasms ofskin | 151(10.01) | 0.0005 |

| 5 | (L40) Psoriasis | 239(5.85) | 4 | (L40) Psoriasis | 211(6.56) | 0.2103 | 5 | (L70) Acne | 119(6.36) | 7 | (L70) Acne | 73(4.84) | 0.0578 |

| 6 | (L70) Acne | 207(5.07) | 7 | (L70) Acne | 123(3.82) | 0.0107 | 6 | (L57) Actinickeratosis | 112(5.99) | 5 | (L57) Actinickeratosis | 85(5.64) | 0.6661 |

| 7 | (D23) Otherbenignneoplasms of skin | 186(4.55) | 6 | (D23) Otherbenignneoplasms of skin | 176(5.47) | 0.0721 | 7 | (B07) Viralwarts | 96(5.13) | 6 | (B07) Viralwarts | 81(5.37) | 0.7556 |

| 8 | (B07) Viral warts | 166(4.06) | 8 | (B07) Viral warts | 121(3.76) | 0.5123 | 8 | (C44) Othermalignantneoplasms ofskin (basal cellcarcinoma) | 66(3.53) | 8 | (C44) Othermalignantneoplasms ofskin (basal cellcarcinoma) | 61(4.05) | 0.4297 |

| 9 | (L30) Other andunspecifieddermatitis | 140(3.43) | 9 | (L30) Other andunspecifieddermatitis | 112(3.48) | 0.9075 | 9 | (L30) Other andunspecifieddermatitis | 65(3.47) | 9 | (L30) Other andunspecifieddermatitis | 52(3.45) | 0.9748 |

| 10 | (L81) Otherdisorders ofpigmentation | 111(2.72) | 11 | (L81) Otherdisorders ofpigmentation | 75(2.33) | 0.3336 | 10 | (L64)Androgenicalopecia | 65(3.47) | 15 | (L64)Androgenicalopecia | 30(1.99) | 0.0097 |

| 11 | (L20) Atopicdermatitis | 96(2.35) | 10 | (L20) Atopicdermatitis | 76(2.36) | 0.9777 | 15 | (L20) Atopicdermatitis | 47(2.51) | 10 | (L20) Atopicdermatitis | 49(3.25) | 0.1980 |

Data are expressed as absolute number and percentages (%).

Our study has the advantage of evaluating changes in the frequency of clinical diagnoses in a representative sample of all Spanish consultations. We observed significant variation in acne (L70), which was more common in the cold period, while other benign neoplasms of skin (D23), rosacea (L71) and other follicular disorders (L73), were more common in the hot period. Our results were similar to those of Hancox et al,1 that only described the 15 most common diagnosis and also found seasonal differences in the frequency of actinic keratosis, dyschromia, psoriasis and seborrheic dermatitis. Another study, including only pathology results, found significant changes over the year in different diseases such as perniosis (chilblains) (more common in winter and spring), hand, foot, and mouth disease (more prevalent in summer and autumn) and erythema multiforme (more common in spring and summer).2 Some of the differences in our study disappeared after adjustment, meaning that the variables adjusted for could explain part of the differences in the frequency of rosacea and other follicular disorders.

The observation that acne was significantly more prevalent in January compared to May is in accordance with previous studies which suggests that acne worsens in the winter.1,7 Decreased inflammation from ultraviolet light-induce immune suppression has been proposed as a key factor in this phenomenon. Furthermore there is some evidence that sun and phototherapy decrease the reactivity of epidermal Langerhans cells,10 which could be involved in acne inflammation at some level.11 A recent study which evaluate the seasonal variation of acne supports our results showing that acne worsen in the winter.8 We also hypothesize that general practitioners could be more prone to refer the patients to the dermatologist in the cold period for the treatment of acne with oral retinoids.

Our data shows that the clinical diagnosis of other benign neoplasms of skin(D23), was more prevalent in the hot period. A possible explanation for this phenomenon is that in this period of the year people and doctors are more aware of these lesions because of the public awareness campaign on sun protection and early detection of skin cancer. It has also been proposed that in this season the climate becomes warm enough to encourage lighter clothes that expose more skin area so people are aware of their lesions and seek consultation.12

Our data for patients under 18 showed that haemangioma and lymphangioma(D18) were more prevalent in the hot period. We have no explanation for this phenomenon that could result from chance.

Some of the differences that we found between private and public consultations are probably due to differences in the overall clinical diagnoses, as asymptomatic benign lesions and aesthetic complaints are not treated in the public health system.

Possible limitations of the present study include the reduction of dermatologists who participate in the second period of the study, although the percentages of participation were quite adequate for this type of surveys (over 60%). In addition, our results only have relevance for comparisons with data from regions with similar temperate climates. Due to feasibility reasons, we chose the cold period in the coldest part of the year, but the hot period was before the start of summer, as a survey during a holiday period would be more likely to have a low response rate. This might decrease the differences between the compared periods. Another limitation is that access to private care is usually direct, with short waiting lists, while in private public practice waiting lists are frequently long, and this might decrease the differences between periods in public practice. Lastly, we did not have data to describe full changes over the whole year, but only a sample of two different periods, limiting the ability to fully describe seasonality.

In conclusion, most clinical diagnoses did not show variation in both periods, but a few showed seasonal changes: acne, benign neoplasms of the skin, rosacea, and other follicular disorders (likely folliculitis). These changes could be due to the diseases themselves or to changes in the demand for consultation.

FUNDINGDIADERM Project has been promoted by the Fundacion Piel Sana AEDV, with financial support from Novartis, that did not participate in the analysis or interpretation of data nor in the preparation of the manuscript.

Regional coordinators: Agustín Buendía, Pablo Fernández-Crehuet, Husein Husein-ElAhmed, Jesús Vega, Agustín Viera, José Manuel Carrascosa, Marta Ferrán, Enrique Gómez, Lucia Ascanio, Ignacio García Doval, Salvador Arias and Yolanda Gilaberte

Participants: Juan A. Sánchez, Amalia Serrano, Rosa Castillo, Ramón Fernandez, José Armario, Carolina Lluc Cantalejo, Cristina Albarrán, María Cruz Martín, Juan Antonio Martín, Román Barabash, Lara Pérez, Manuel Salamanca, Carlos Hernández, José Francisco Millán, Inmaculada Ruiz, Susana Armesto, Marta González, Valia Beteta, Concepción Cuadrado de Valles, Pilar Cristóbal, María Magdalena Roth, Juan Garcias, Ricardo Fernandez de Misa, Estela García, María del Pino Rivero, José Suárez, Birgit Farthmann, Alba Álvarez, Irene García, Caridad Elena Morales, María Cristina Zemba, Trinidad Repiso, Carmen Sastre, María Ubals, Alejandro Fernández, Urbà González, Ramón Grimalt, Sara Gómez, Ingrid López, Franco Antonio Gemigniani, María José Izquierdo, Fernando Alfageme, Nuria Barrientos, Laura María Pericet, Santiago Vidal, Celia Camarero, Pablo Lázaro, Cristina García, María Pilar De Pablo, Pedro Herranz, Natalia del Olmo, María Castellanos, Natalia Jiménez, Sonsoles Aboín, Isabel Aldanondo, Adriana Juanes, Dulce María Arranz, Olga González, Luis Casas, Juan José Vázquez, Carmen Peña, José Luis Cubero, Carlos Feal, María Eugenia Mayo, Nicolás Iglesias, Rafael Rojo, Elfidia Aniz, Sabrina Kindem, Nerea Barrado, Marisa Tirado, Ester Quecedo, Isabel Hernández, Antonio Sahuquillo, Rebeca Bella, Ramón García, Anaid Calle, Francesc Messeguer, Alberto Alfaro, Luisa Casanova, Libe Aspe, María Pilar Moreno, Izaskun Trébol, Gonzalo Serrano, Víctor Manuel Alcalde, Patricia García and Carmen Coscojuela.

Please cite this article as: Gonzalez-Cantero A, Arias-Santiago S, Buendía-Eisman A, Molina-Leyva A, Gilaberte Y, Fernández-Crehuet P, et al. ¿Existe variación en los diagnósticos dermatológicos entre la temporada de frío vs calor? Un subanálisis del estudio DIADERM (España 2016) Eczema y urticaria en Portugal. 2019;37:734–743.