Cutaneous metastases of prostate cancer are extremely rare. We present 2 cases of distant cutaneous metastases at atypical locations of prostate adenocarcinoma, and highlight the value of 2 immunohistochemical stains—prostatic acid phosphatase and prostate-specific membrane antigen—that can aid diagnosis, particularly in cases with negative staining for prostate-specific antigen.

Las metástasis cutáneas de cáncer de próstata son extremadamente infrecuentes. Presentamos 2 casos de metástasis cutáneas a distancia de adenocarcinoma de próstata, con localización atípica y destacando 2 tinciones inmunohistoquímicas que pueden ayudar al diagnóstico (fosfatasa ácida prostática y el antígeno prostático específico de membrana prostática), fundamentalmente en aquellos casos en los que el antígeno prostático específico es negativo.

Prostate cancer is one of the most common noncutaneous malignant tumors in men and a frequent cause of cancer-related death. Despite its high prevalence and incidence, skin metastases are extremely rare. Few cases of skin metastases from prostate cancer have been reported in the literature. Most skin metastases have been on the penis and scrotum; distant skin metastases are much less common and have an atypical clinical presentation that can delay diagnosis.1

We present 2 cases of patients with distant skin metastases of prostate cancer, drawing attention to the unusual site and clinical presentation.

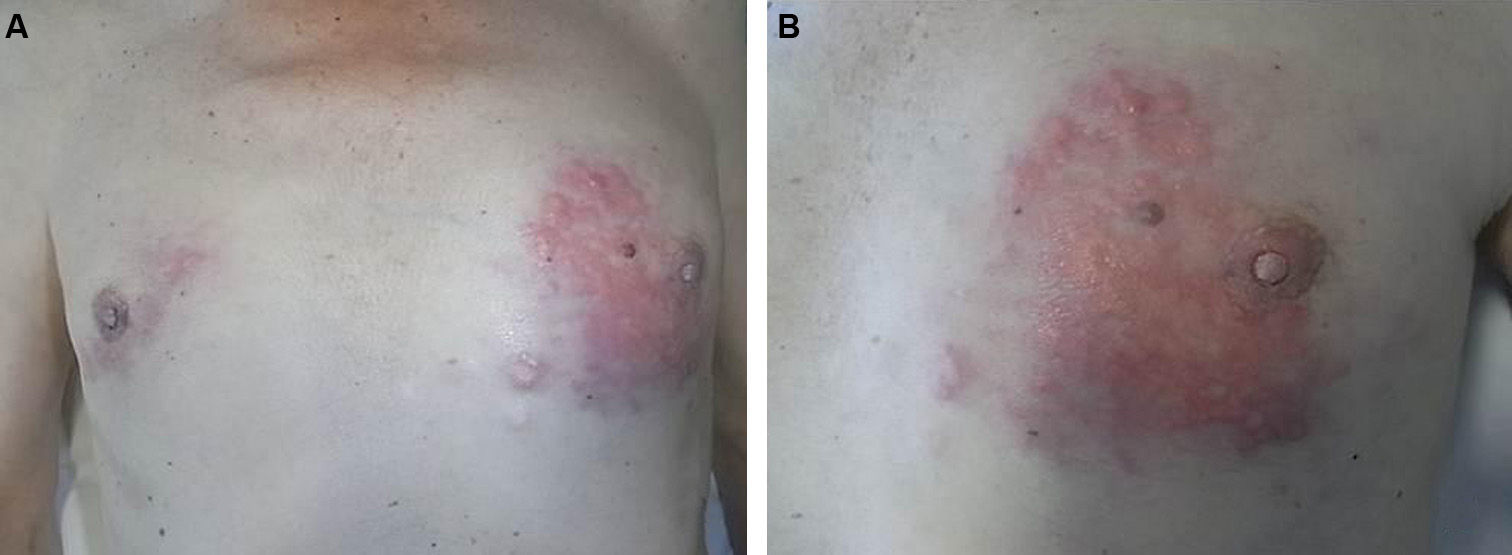

Case 1The patient was a 66-year-old man with stage iv, Gleason 8 (5+3) adenocarcinoma of the prostate diagnosed 11 years earlier and treated by radical prostatectomy, pelvic radiotherapy, hormone therapy, and chemotherapy. He presented 2 infiltrated, stony-hard plaques in a linear distribution on both breasts, the larger one being on the left breast. The plaques were formed of yellowish papular lesions that had first appeared approximately a year earlier and had increased progressively in size (Fig. 1, A and B). The patient described induration of both breasts in recent years; this had been interpreted as gynecomastia related to his hormone treatment. During follow-up in oncology, the patient had presented a progressive elevation of prostate specific antigen (PSA) levels in blood over the previous months (PSA 7.45ng/ml in the latest blood tests before consultation; PSA, 3.38ng/ml 2 months earlier).

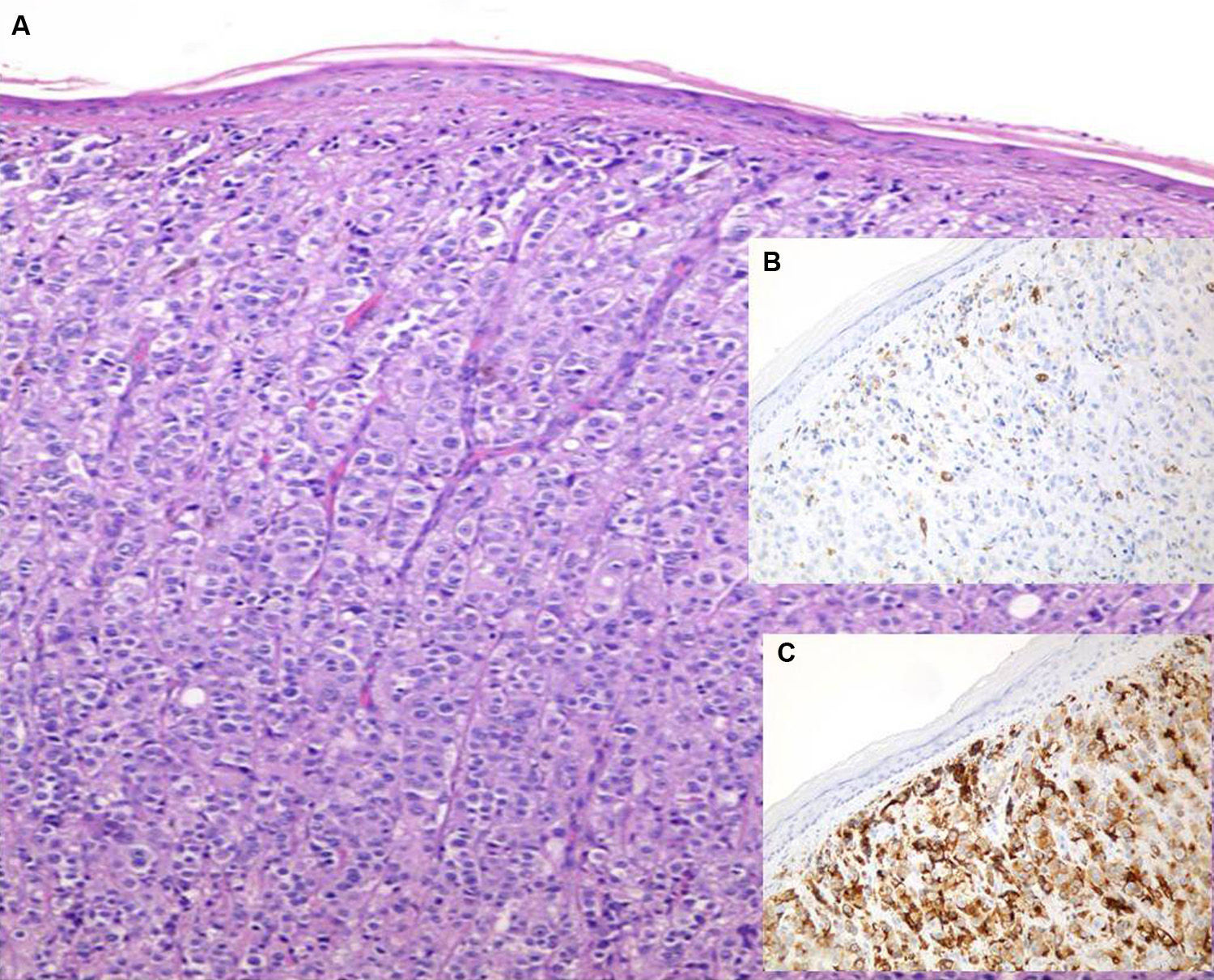

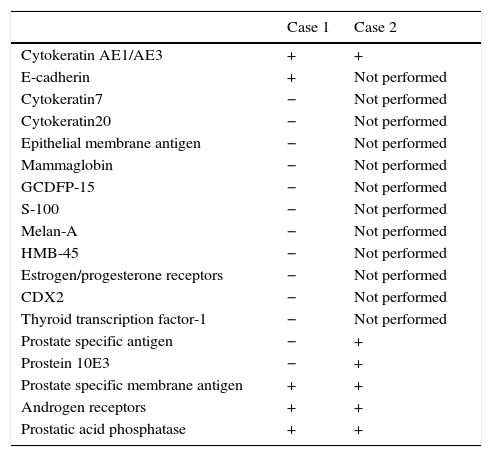

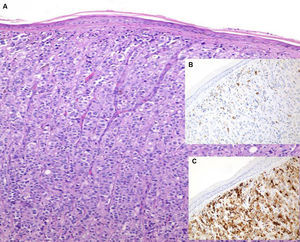

Skin biopsies were taken from both plaques. Routine techniques showed poorly differentiated tumor cells with an epithelioid appearance and a diffuse growth pattern. Immunohistochemistry (Table 1) was positive for cytokeratin AE1/AE3, prostate specific membrane antigen (PSMA) 3E6, E-cadherin, androgen receptors, and prostatic acid phosphatase (this last parameter was positive in a smaller number of tumor cells) (Fig. 2, A-C). These findings strongly supported the diagnosis of skin metastases from the patient's adenocarcinoma of the prostate and ruled out a primary breast tumor.

Immunohistochemistry.

| Case 1 | Case 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Cytokeratin AE1/AE3 | + | + |

| E-cadherin | + | Not performed |

| Cytokeratin7 | − | Not performed |

| Cytokeratin20 | − | Not performed |

| Epithelial membrane antigen | − | Not performed |

| Mammaglobin | − | Not performed |

| GCDFP-15 | − | Not performed |

| S-100 | − | Not performed |

| Melan-A | − | Not performed |

| HMB-45 | − | Not performed |

| Estrogen/progesterone receptors | − | Not performed |

| CDX2 | − | Not performed |

| Thyroid transcription factor-1 | − | Not performed |

| Prostate specific antigen | − | + |

| Prostein 10E3 | − | + |

| Prostate specific membrane antigen | + | + |

| Androgen receptors | + | + |

| Prostatic acid phosphatase | + | + |

After the diagnosis of skin metastases, and in view of the progression of the bone metastases, chemotherapy treatment was reinitiated. The clinical course was poor and the patient died a year later.

Case 2This 86-year-old man was diagnosed with stage iv, Gleason 7 (3+4) adenocarcinoma of the prostate in 2010 and had been treated with total hormonal blockade and chemotherapy. Three years later the patient consulted for asymptomatic skin lesions that had arisen approximately a week earlier and had increased progressively in size and number. Physical examination revealed indurated, erythematous, papules grouped on the anteromedial surface of the right knee and isolated nonindurated lesions of similar appearance but smaller size that had arisen hours earlier on the anterior surface of the same leg (Fig. 3, A and B).

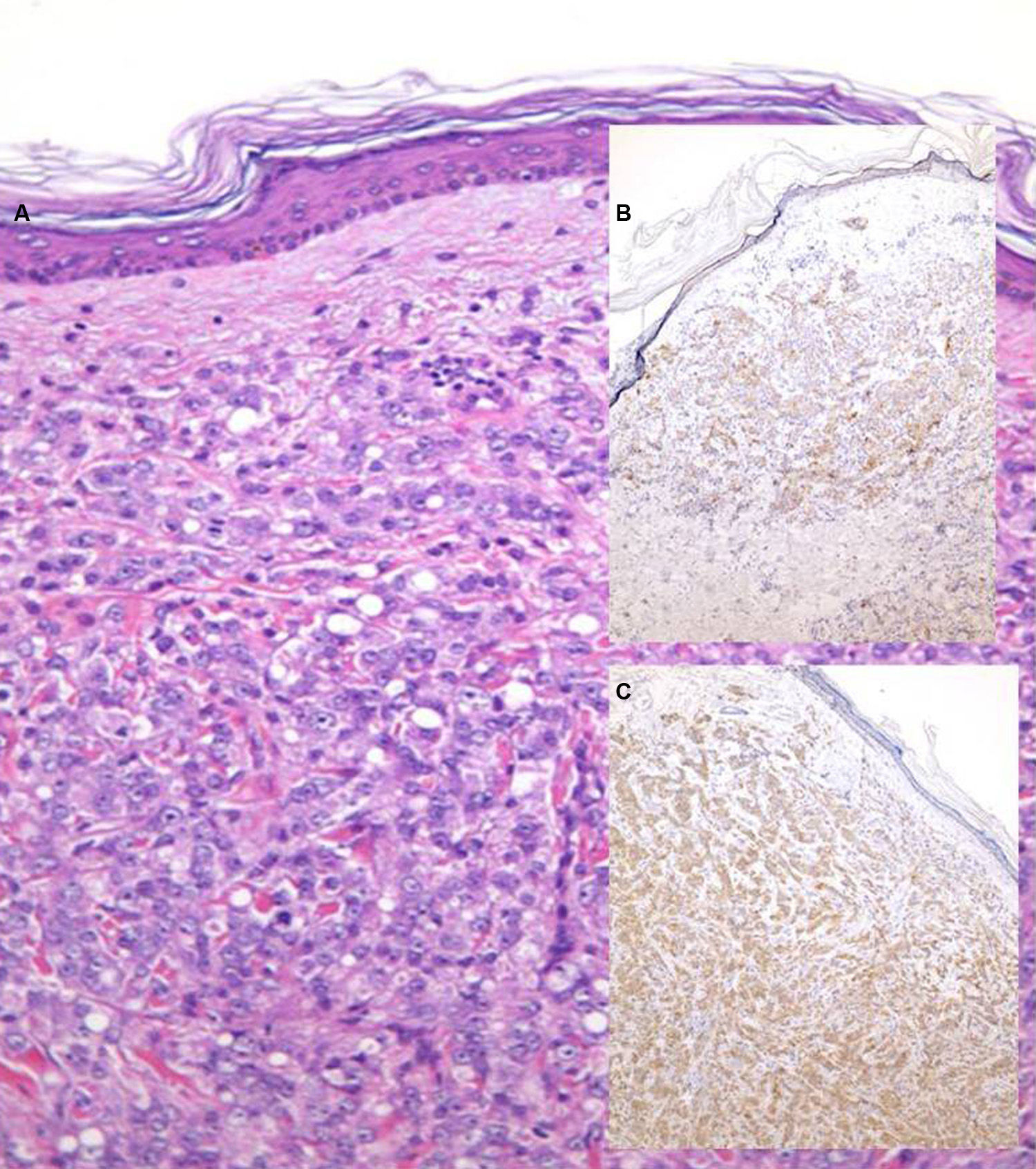

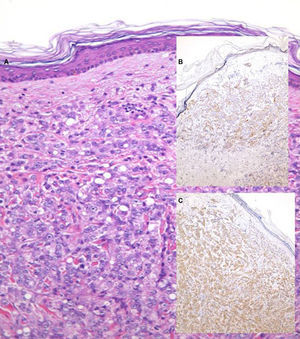

Biopsy of a lesion showed a poorly differentiated tumor of epithelial appearance, with a diffuse growth pattern. Immunohistochemistry was positive for cytokeratin AE1/AE3, PSA, androgen receptors, prostatic acid phosphatatase, prostein (Fig. 4, A-C), and PSMA (present in only a small number of tumor cells) (Table 1). Based on this immunohistochemistry profile, the tissue was reported as skin metastases from a poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma, compatible with a prostatic origin. The patient died a month later.

DiscussionProstate cancer is usually associated with bone, lung, liver, and lymph node metastases; skin involvement is very rare (less than 1%). When prostate cancer metastasizes to the skin, the metastases typically appear locally as asymptomatic papules or nodules, mainly on the genitalia, suprapubic region, or root of the thighs. Distant skin metastases are rarer and can affect the chest and head, without the typical nodular morphology, with a clinical presentation that can mimic other skin diseases (zosteriform distribution, lesions of sclerodermiform or inflammatory appearance, etc.).2–5

The incidence of skin metastases from internal tumors appears to have increased in recent years—this may be due to better diagnosis rather than a true increase—but even so, these metastases continue to be rare in clinical practice, with an estimated incidence of 0.7% to 9% of patients with internal tumors, depending on the series. The prostatic origin of skin metastases is very rare.

The tumors that most commonly give rise to skin metastases have been described according to the site of the metastases. Lung and breast cancers metastasize most frequently to the chest and, together with renal and digestive tract tumors, to the limbs.6

Hypotheses on the route of spread of prostate carcinoma to the skin include direct invasion and lymphatic or hematogenous spread, or a combination of these routes; the exact mechanism remains unclear. Few studies have investigated the mechanisms that favor the spread of some malignant internal tumors to the skin, although some cytokines that might favor metastatic tumor spread have recently been implicated.3,5,6

Immunohistochemistry can help to confirm the tumor of origin of skin metastases. Although PSA is relatively specific, it can also be expressed by breast carcinomas (infiltrating ductal and apocrine carcinomas), small cell lung cancer, and poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinomas. The absence of positivity for PSA does not exclude a prostatic origin of a tumor, as undifferentiated tumors can lose the ability to express PSA. In these cases, the measurement of prostatic acid phosphatase, PSMA, and prostein can be useful.4,7,8 In our first case, a negative PSA can be explained by the previous hormone therapy. The site on the breast, together with the negative PSA result, required us to exclude other possibilities, primarily breast carcinoma; cytokeratin7, epithelial membrane antigen, mammaglobin, GCDFP-15, estrogens, and progesterone were therefore measured. Androgen receptors may be positive in some breast carcinomas, mainly in grade iii tumors, and this parameter is therefore unhelpful in the differential diagnosis. The other diagnosis that histologically must always be taken into account is melanoma. For this we studied S100, Melan-A, and HMB 45. Cytokeratin20 was measured to exclude other possible metastatic cancers (such as colon).

The skin lesions in prostate cancer typically appear late and are associated with a very poor prognosis, with a mean estimated survival of 7 months.3,4

Treatment options in skin metastases from prostate cancer are mostly palliative, and include surgery, radiotherapy, and intralesional chemotherapy.3,4

In conclusion, we have presented 2 cases of distant skin metastases from prostate cancer. Fewer than 30 cases have been reported in the literature (Table 2). We consider that this may be an underdiagnosed disease and note the atypical clinical presentation that can occur in some patients. We also draw attention to the poor prognosis associated with the appearance of skin metastases in prostate cancer, with a survival of only months.

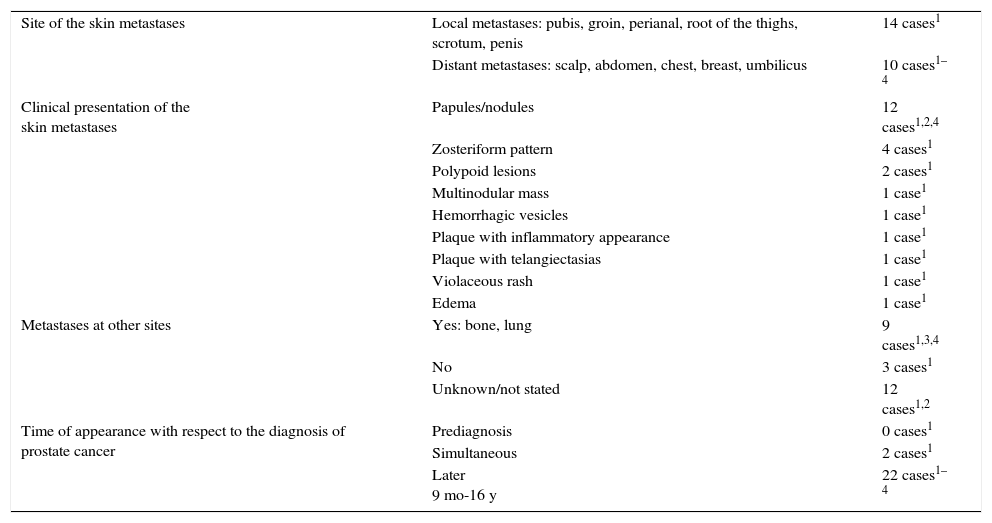

Cases of Skin Metastases From Prostate Cancer Reported in the Literature.

| Site of the skin metastases | Local metastases: pubis, groin, perianal, root of the thighs, scrotum, penis | 14 cases1 |

| Distant metastases: scalp, abdomen, chest, breast, umbilicus | 10 cases1–4 | |

| Clinical presentation of the skin metastases | Papules/nodules | 12 cases1,2,4 |

| Zosteriform pattern | 4 cases1 | |

| Polypoid lesions | 2 cases1 | |

| Multinodular mass | 1 case1 | |

| Hemorrhagic vesicles | 1 case1 | |

| Plaque with inflammatory appearance | 1 case1 | |

| Plaque with telangiectasias | 1 case1 | |

| Violaceous rash | 1 case1 | |

| Edema | 1 case1 | |

| Metastases at other sites | Yes: bone, lung | 9 cases1,3,4 |

| No | 3 cases1 | |

| Unknown/not stated | 12 cases1,2 | |

| Time of appearance with respect to the diagnosis of prostate cancer | Prediagnosis | 0 cases1 |

| Simultaneous | 2 cases1 | |

| Later 9 mo-16 y | 22 cases1–4 |

The authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this research.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they followed their hospital's regulations regarding the publication of patient information.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no private patient data are disclosed in this article.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Rodríguez-Lojo R, Castiñeiras I, Rey-Sanjurjo JL, Fernández-Díaz ML. Metástasis cutáneas a distancia de cáncer de próstata: 2 casos. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2016;107:e52–e56.