Cryptococcoid Sweet syndrome is a term coined recently by Wilson J et al1 to describe a rare variety of Sweet syndrome, which has a histologic profile that is indistinguishable under hematoxylin and eosin staining from gelatinous cryptococcosis. Diagnosis is established by positivity for staining with myeloperoxidase in the presence of negative stains for fungi. To date, 8 cases of neutrophilic dermatosis have been reported with these histopathology characteristics, all of them in dermatopathology journals.1–4 We describe a new case of cryptococcoid Sweet syndrome, where infection by Cryptococcus spp was considered not only because of the histopathology profile but also because of the clinical characteristics of the skin lesions.

Case DescriptionAn 18-year-old woman presented a history of episodes of different neutrophilic dermatoses (pyoderma gangrenosum and Sweet syndrome) between the ages of 6 and 12 years. She subsequently developed antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-positive vasculitis, with terminal kidney failure and malignant hypertension, causing her to be put on hemodialysis. The patient was undergoing treatment with azathioprine, prednisone, losartan, valaciclovir, and trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole. Forty-eight hours after undergoing magnetic resonance angiography, she presented molluscum-like lesions on the face (Fig. 1) and blisters and erythematous lesions on the backs of the hands, accompanied by fever and neutrophilia of 9910 neutrophils/mm3 (82.5% leukocytes). An adverse reaction to the contrast medium was suspected and boluses of methylprednisone were administered; the patient was assessed by the dermatology department. An infectious process (cryptococcosis, tuberculosis, histoplasmosis, etc.) was suspected and biopsies were performed and microbiology samples were taken. The lesions resolved after a few days and the patient remained lesion-free and in excellent general health.

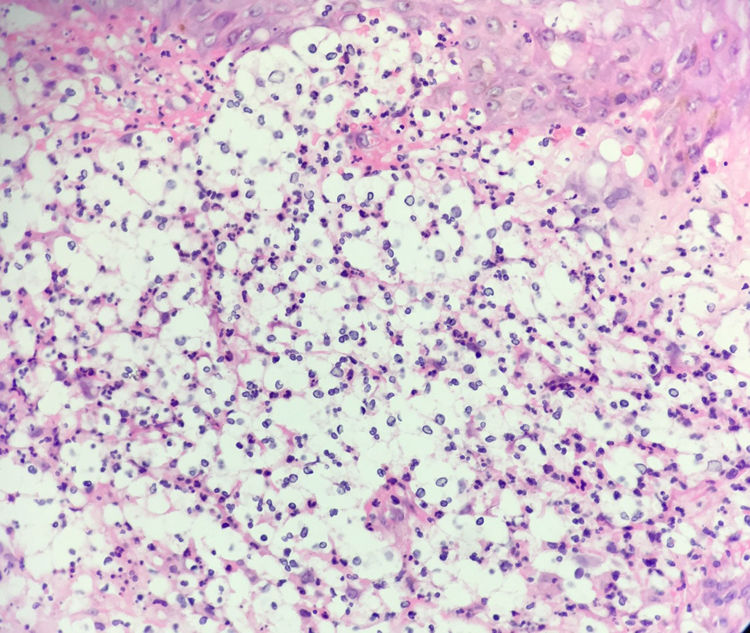

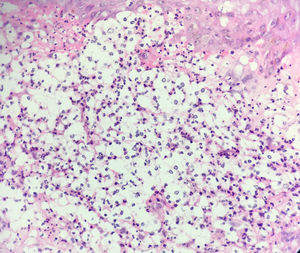

Histology revealed a dermal inflammatory infiltrate with neutrophils, vacuolated spaces, and yeast-like structures that appeared to have a capsule, all of which suggested gelatinous cryptococcosis (Fig. 2). However, the lesions had regressed with corticosteroid treatment, the chest x-ray was normal, and cultures, special stains, and antigenemia for Cryptococcus spp were negative.

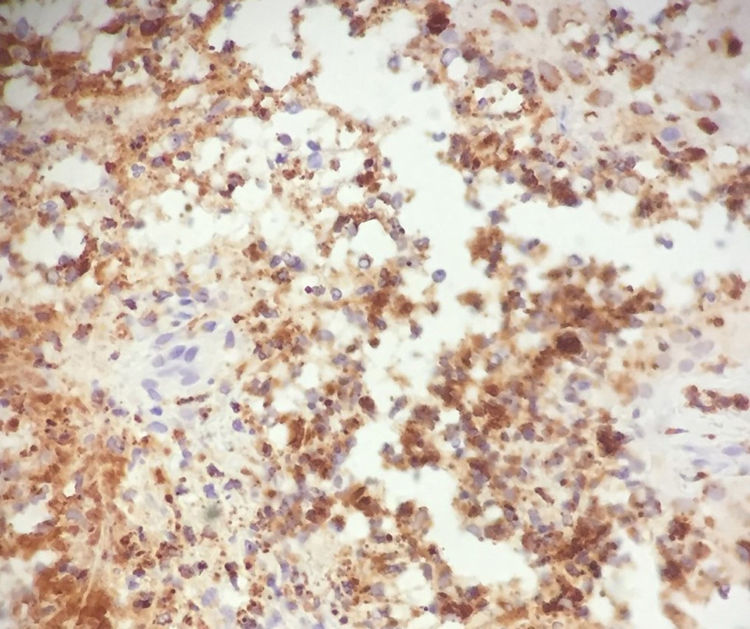

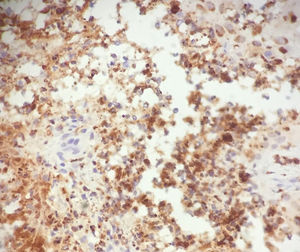

In light of the history of neutrophilic dermatosis, the presence of fever and neutrophilia, resolution of symptoms with corticosteroid treatment, and negativity of the microbiology analyses, a diagnosis of cryptococcoid Sweet syndrome was reached. A positive stain for myeloperoxidase confirmed the diagnosis (Fig. 3).

DiscussionAlthough the term cryptococcoid Sweet syndrome was coined in 2017 by Wilson et al, the first cases of this histologic phenomenon were described by Ko et al in 2013.2 Those authors reported 3 cases of neutrophilic dermatosis, where the histologic profile showed a dermal inflammatory infiltrate with neutrophils, vacuolated spaces, and yeast-like basophilic structures that appeared to be encapsulated—a profile highly suggestive of disseminated cryptococcosis.

Microbiology studies and special stains did not confirm infection in any of the 3 cases. In 2 of the cases, electron microscopy revealed autolyzed neutrophils.

The cause of this phenomenon is still the subject of debate. Ko et al postulate that it may be due to autophagic programmed cell death that leads to extensive cytoplasmic vacuolization. Another possibility is that it is due to artefacts of laboratory technique. Finally, given that the 3 original patients were women over 75 years of age, the authors suggest that these phenomena may be linked to degenerative collagen alterations. This hypothesis, however, does not hold with patients of a young age, particularly our patient, who is the youngest of those reported to date (18 years).

It should be noted that, to date, in all published cases, suspicion of cryptococcosis arises from a suggestive histologic profile; in no case was infection by Cryptococcus spp considered as a clinical diagnosis. We therefore consider cryptococcoid Sweet syndrome to be a diagnostic challenge, not only for pathologists but also for clinicians, and we highlight the idea that in all infectious processes, the definitive diagnosis must meet clinical, histopathologic, and microbiologic criteria.

Moreover, this case of cryptococcoid Sweet syndrome presented in association with an ANCA-positive vasculitis. The association between neutrophilic dermatosis and ANCA-positive vasculitis is well known, although the pathogenic link is not fully understood.5 In this context, it is important to note that histologic changes of this type have also been described in vasculitis and that entity should also be included in the differential diagnosis.6

In conclusion, we present a new case of cryptococcoid Sweet syndrome, in which the differential diagnosis with disseminated cryptococcosis was due not only to the histologic profile but also to the clinical picture (sudden appearance of molluscum-like papules in an immunosuppressed patient). Thus, in the case of a clinical and histologic suspicion of disseminated cryptococcosis, we must consider Sweet syndrome in the differential diagnosis, particularly if the relevant microbiologic criteria are not met.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Mazzei ME, Guerra A, Dufrechou L, Vola M. Síndrome de Sweet criptococoide: simulador de criptococosis tanto clínica como histológicamente. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2021;112:79–80.