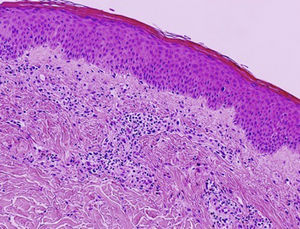

In 2006, Kossard and coworkers coined the term urticarial dermatitis (UD) to describe a histological skin reaction pattern with a broad clinical spectrum. UD is primarily characterized by the presence of urticarial, erythematous, pruritic papules or plaques and eczematous lesions.1 Biopsy of urticarial areas reveals a normal stratum corneum, minimal spongiosis, and perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate of the papillary dermis with eosinophils (with or without neutrophils)1 (Fig. 1). In this descriptive observational study we describe the clinical and histological findings in 6 patients with a diagnosis suggestive of UD who were treated at the Eczema Unit of the Dermatology Service of a tertiary hospital in 2015 and 2016. Table 1 shows corresponding data on epidemiology, comorbidities, clinical presentation, initial clinical suspicion, diagnostic tests, final diagnosis, disease duration at the time of diagnosis, follow-up period, treatment, and progression.

Descriptive Data: Patient Characteristics, Clinical Presentation, and Treatment.

| Sex | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Female |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 71 | 88 | 62 | 77 | 45 | 77 |

| Comorbidities | DM Dyslipidemia Essential hypertension | BPH | Dyslipidemia DM | DM BPH Ischemic heart disease | N/A | DM Osteoporosis WM Ovarian teratoma |

| Dermographism | + | + | - | - | + | + |

| Initial clinical suspicion | Scabies Eczema BP UD CSU | BP Eczema UD CSU | UD CSU Urticaria-vasculitis | Allergic contact dermatitis UD BP DR | Scabies Eczema CSU Dermatitis herpetiformis | CSU Urticaria-vasculitis DR BP |

| Histology | Normal epidermis Superficial dermal perivascular, lymphocytic, and eosinophilic infiltrate with presence of eosinophils DIF– | Focal parakeratosis, mild eosinophilic spongiosis, and poor vacuolization of the basement membrane Superficial perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate Interstitial lymphocytic and eosinophilic infiltrate DIF– | Normal epidermis Superficial dermal perivascular, lymphocytic, and eosinophilic infiltrate with interstitial eosinophils DIF– | Normal epidermis Superficial dermal perivascular, lymphocytic, and eosinophilic infiltrate DIF– | Normal epidermis Superficial dermal perivascular, lymphocytic, and eosinophilic infiltrate with interstitial eosinophils DIF– | Normal epidermis Mild dermal edema, superficial and interstitial dermal perivascular, lymphocytic, and neutrophilic infiltrate without eosinophils No signs of vasculitis DIF– |

| Other diagnostic tests | BT (IgE, 260 IU/mL; eosinophils, 0.86 × 103/μL) | N/A | N/A | Patch test (negative) | BT: normal | BT (glucose, 195mg/dL; GF, 52 mL/min; CBC, normal) |

| Final diagnosis | UD (DR secondary to vildagliptin) | CSU | CSU | UD (DR secondary to silodosin) | CSU | Schnitzler syndrome |

| Treatment | Permethrin OA OC TC MTX Vildagliptin (interrupted) | OA OC TC | OA OC NSAIDs (interrupted) | OA OC TC Silodosin (interrupted) | Permethrin OA OC TC Montelukast Omalizumab | OA OC TC MTX |

| Treatment response | Good | Good | Good | Good | Good | Poor |

| Delay between onset and diagnosis, mo | 10 | 13 | 3 | 6 | 4 | 6 |

| Follow-up, mo | 13 | 20 | 5 | 10 | 13 | 7 |

Abbreviations: BP, bullous pemphigoid; BPH, benign prostatic hyperplasia; BT, blood test; CBC, complete blood count; CSU, chronic spontaneous urticaria; DIF, direct immunofluorescence; DM, diabetes mellitus; DR, drug reaction; GF, glomerular filtrate; MTX, methotrexate; N/A, not applicable; NSAIDs, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; OA, oral antihistamines; OC, oral corticosteroids; TC, topical corticosteroids; UD, urticarial dermatitis; WM, Waldenström macroglobulinemia.

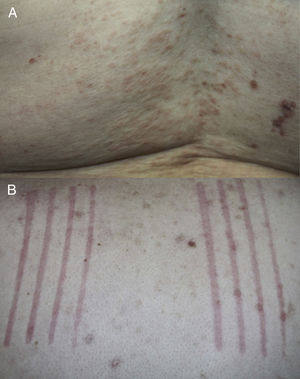

The mean age at UD onset was 70 years (range, 45–88 years). None of the patients had a personal or family history of atopy, urticaria, or any other skin disease. All patients reported having pruritus and in all cases physical examination confirmed the presence of urticarial papules or plaques and clinical signs of dermatitis (Fig. 2A). Dermographism was detected in 4 patients (Fig. 2B). The initial clinical suspicions included UD, chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU), bullous pemphigoid, and eczema. Other clinical entities included in the differential diagnosis were drug reactions, urticaria-vasculitis, scabies, and dermatitis herpetiformis.

In all cases, a final diagnosis was established based on the results of diagnostic tests (CSU in 3 patients, drug reaction in 2 patients, and Schnitzler syndrome in 1 patient). The mean time from disease onset to final diagnosis was 7 months (range, 3–13 months) and the mean duration of follow-up was 11.3 months (range, 5–20 months). All patients were initially treated with oral antihistamines and corticosteroids. Improvement was observed in only 2 patients, both of whom were later diagnosed with CSU. All but 1 patient responded well to targeted treatment once the definitive diagnosis had been established.

UD is not a discrete disorder, but a group of skin diseases that share similar clinical and histological manifestations. In many patients with clinically suspected UD a clinical-pathological correlation can be reached through accurate diagnostic assessment,2 although this can take several months. Pathologists have used the term dermal hypersensitivity reaction pattern to describe UD, despite the absence of a clinical or histological correlation between these presentations.1,3 All cases in this series initially posed a diagnostic challenge, as none could be classified as a specific inflammatory disorder. Ultimately, a final diagnosis was established in all cases. The most common diagnosis was CSU, followed by drug reaction. Our results differ from those previously reported in the literature: Kossard and coworkers found that the most frequent clinical associations were eczema and drug reactions,1 while 47% of the cases in the series by Hannon and coworkers were of idiopathic origin.2 Certain histological clues may facilitate the establishment of a more specific diagnosis,2 particularly if observed in earlier disease stages when the lesions are more edematous and less excoriated. The presence of spongiosis supports a diagnosis of eczema, while its absence is suggestive of urticaria or lesions secondary to either drug reaction or urticaria.1 Because UD can constitute the initial signs of bullous pemphigoid,1,2 it is advisable to perform direct immunofluorescence studies.

UD typically affects elderly patients, especially women.2,4 Because many patients are polymedicated, it can be difficult to identify the causative agent in cases of suspected drug-induced UD. UD lesions have a polymorphous appearance, and exhibit features of urticaria and concomitant or simultaneous dermatitis.4 Eczematous lesions may be caused in part by the use of home remedies to relieve itching. In our study, physical examination revealed dermographism in some patients. Although dermographism is typical of drug reaction, scabies and, above all, CSU, its presence can be particularly helpful in the diagnosis of UD.

UD may involve a T helper 2 (Th2) lymphocyte reaction, which precedes a dominant T helper 1 (Th1) cytokine profile, particularly in cases of atopic dermatitis.1,5 This induces the production of interleukin (IL)-4, IL-5, and IL-10, all of which can give rise to eosinophilia and urticarial reactions.5

The therapies most commonly used to treat UD include oral antihistamines, topical and systemic corticosteroids, narrowband ultraviolet B radiation, and topical calcineurin inhibitors, usually with unsatisfactory results.1,2,4 Some reports have described good responses to treatment with other therapeutic agents, including cyclosporins, mycophenolate mofetil, azathioprine, dapsone, and hydroxyurea.3,6

In conclusion, UD is a common manifestation of several distinct skin diseases that appear to share a similar pathophysiological mechanism. A final diagnosis can be established after exhaustive evaluation of the information obtained from anamnesis, histology, and other additional tests. The detection of dermographism in the physical examination may help orient the diagnosis towards UD. However, this finding should not be considered a specific sign of any condition in particular. In our opinion, UD is a useful term to describe a skin reaction mainly observed in the elderly, the clinical characteristics of which mimic those of several skin diseases. In many cases, a definitive diagnosis can only be established after long-term follow up.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: García del Pozo MC, Poveda I, Álvarez P, Silvestre JF. Dermatitis urticante. Un patrón de reacción cutánea. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2018;109:929–932.