Turret exostosis, otherwise known as acquired osteochondroma, is a rare bone disorder originally described by Wissinger et al1 in 1966 as a smooth, dome-shaped, extracortical mass arising from the dorsum of the middle or proximal phalanges of the fingers; it has, however, also been described in other parts of the body. It is believed to be the result of a reactive process in the bone, triggered by injury, which eventually leads to areas of mature bone formation.2 Although Turret exostosis originates in the bone, it can manifest as a subcutaneous nodule. There are few reports of these nodules in the literature and none in dermatology journals.

We describe the case of a 56-year-old woman, with no relevant past history, who consulted her dermatologist due to a nodular lesion that had been progressively growing on 1 of her fingers for 3 months. The lesion measured 1cm in diameter, was slightly pedunculated and indurated on palpation, and the overlying skin was a normal color, although there were some slightly erythematous areas. The nodule was located on the palmar aspect of the middle phalanx of the right middle finger (Fig. 1). Radiography showed a densely radio-opaque, well-circumscribed lesion measuring about 2cm in diameter, separated from the underlying bone.

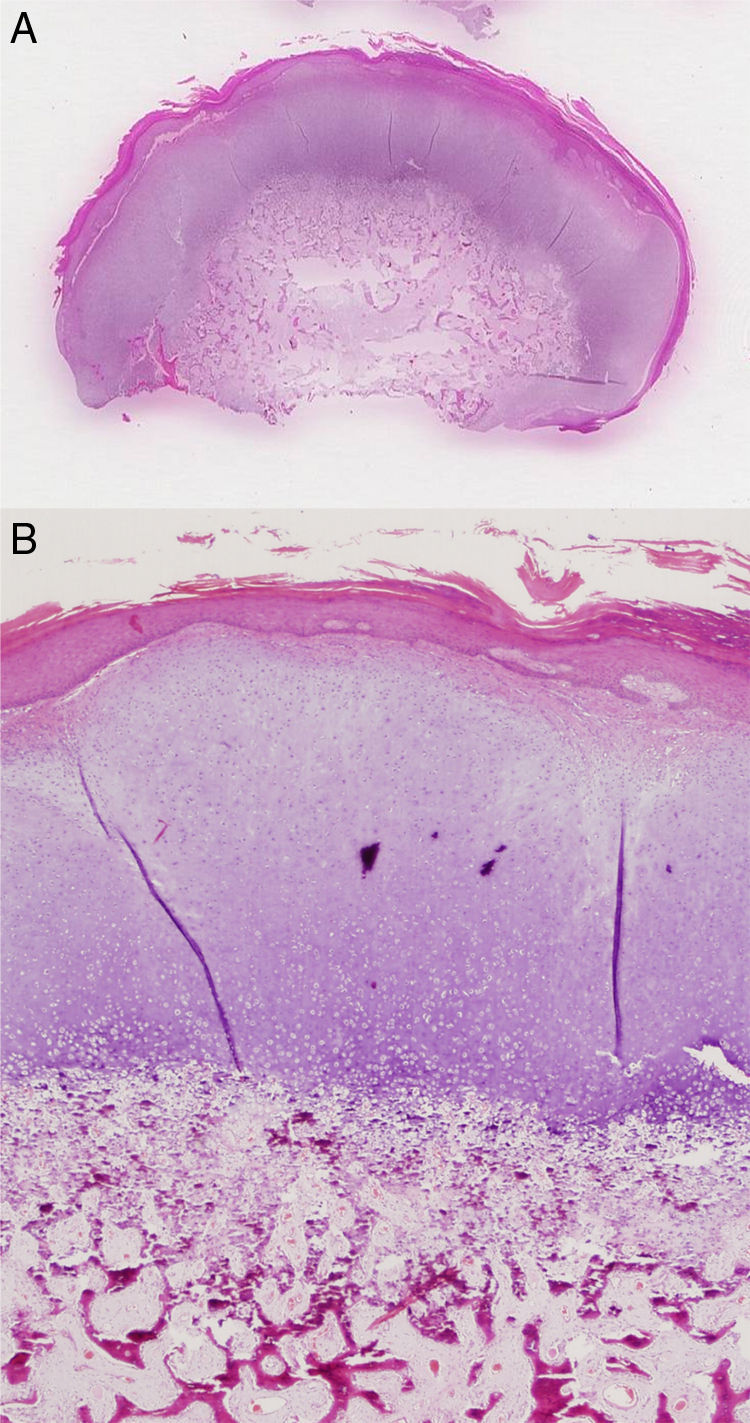

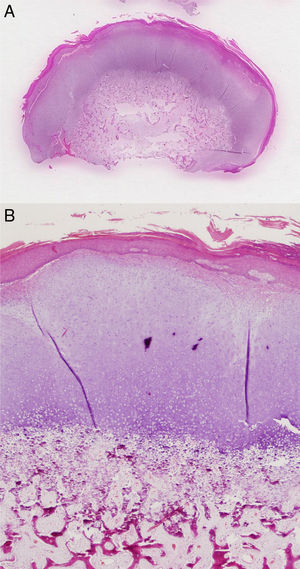

The lesion was excised and histopathology showed an expansive subepidermal lesion. The surface of the lesion had a mature osteocartilaginous cap and a transitional area with signs of enchondral ossification and bone tissue trabeculae. The trabeculae were covered by a small population of osteoblasts without cytologic atypia. The intertrabecular spaces contained lax, highly vascularized fibrous tissue, and the epidermis showed acanthosis and a thick stratum corneum, consistent with acral skin (Fig. 2). On the basis of these findings, a diagnosis of Turret exostosis was established. The lesion had not recurred 1 year after excision.

A and B, Histological findings (hematoxylin-eosin staining) showing the surface of the lesion with a mature osteocartilaginous cap and a transitional area with signs of enchondral ossification and bone tissue trabeculae. B, Lax, highly vascularized fibrous tissue in the lower part of the image.

Turret exostosis is currently classified as a rare complication of minor injuries. The underlying mechanism is usually an injury that causes a subperiosteal hematoma. Because the hematoma is unable to drain, it gradually becomes ossified.2,3 The patient described in this letter does not remember injuring her finger, but she might have done so without noticing.

Also of interest in this case is the fact that the lesion arose from the palmar aspect of the finger as practically all the reports of Turret exostosis of the hands to date, with the exception of a thumb lesion,4 have described lesions on the dorsal surfaces. As the lesion grows, it normally becomes painful and can restrict movement; there have even been reports of Turret exostosis causing ruptured tendons.5 Our patient had no symptoms but decided to visit her dermatologist because she was worried about the size of the lesion.

Radiographically, the lesion appeared as a well-delimited bone mass arising from the cortex of the underlying bone, but with no communication with the medullary canal; this is similar to what is seen in osteochondroma.5 The differential diagnosis should include osteochondroma, juxtacortical chondroma, florid reactive periostitis, bizarre parosteal osteochondromatous proliferation (BPOP) (otherwise known as Nora's lesion), osteosarcoma, and chondrosarcoma.3,6

Turret exostosis should not be excised until at least 4 to 6 months after the injury that triggered its development.1 Poor surgical techniques and premature excision can cause lesions to recur.7 The overall rate of recurrence of Turret exostosis of the hands is 20%.5 Recurring lesions usually appear within 6 months of excision, and they normally present with more irregular calcification than the original lesions.2 In our patient, excision was complete and there has been no recurrence.

Several authors have suggested that Turret exostosis, BPOP, and florid reactive periostitis are part of a spectrum of reactive bone disorders.2,8,9 Florid reactive periostitis is hypothesized to be the first stage, in which there would be a proliferation of spindle cells with minimal osteocartilaginous growth. With time, the new bone and the cartilaginous metaplasia would become more evident, giving rise to BPOP, and in the final stage, Turret exostosis, this mature bone area would give rise to a bone base with a cartilaginous cap.9,10 This hypothesis, which was initially proposed by histopathology experts,2 has found support in radiography studies and is currently considered the most plausible explanation for these reactive bone processes.

To conclude, we have presented a case of Turret exostosis, a rare entity that should be recognized by dermatologists as it can manifest as a subcutaneous nodule.

Please cite this article as: Cañueto J, et al. Exostosis de Turret: osteocondroma adquirido. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2011;102:474-475.