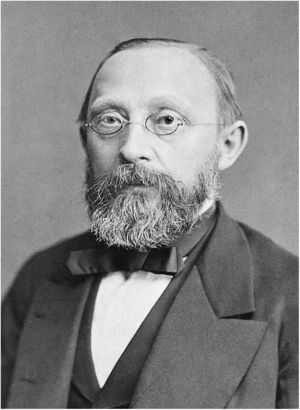

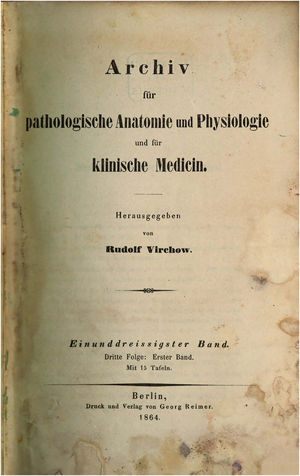

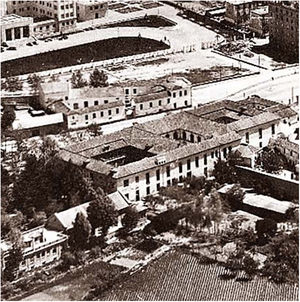

When Rudolf Virchow came to Spain in 1880, he was already an expert pathologist (Fig. 1). Among his many contributions he had made important observations on cell theory (Fig. 2), identified leukemia, established the journal Archiv für pathologische Anatomie und Physiologie und für Klinische Medicin (Fig. 3), and been appointed to the chair of Pathological Anatomy in the University of Berlin.

In 1880, there was a great deal of debate in the field of infectious diseases. Some scientists considered microorganisms to be the causative agents of these diseases. Others, including Virchow, believed that the presence of such microorganisms in diseased organs did not necessarily indicate that they were the cause of the infection. This debate focused mainly on the most important infectious diseases of the time, such as syphilis and tuberculosis, but leprosy was also included. In the case of leprosy, the causative agent had been identified by Hansen in 1873. By 1800, leprosy was no longer endemic in some parts of Europe, but it was still found (albeit at a lower incidence) in Spain, Portugal, the Baltic region, European Russia, Turkey, Italy, and Greece.1 In the 1850s, there were still a considerable number of leprosy patients in several provinces in southern and western Spain (Fig. 4).2 One of these provinces—Granada—had a very specialized leprosy hospital: the Hospital de Leprosos de San Lázaro. The hospital had been founded in 1502 by the Catholic Monarchs, Queen Isabella and King Ferdinand, specifically to house patients with leprosy. The site of the original building was a small square in Granada but the hospital was moved in 1512 to a more central area (Fig. 5), where it remained until finally demolished in 1973.

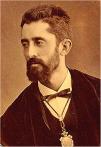

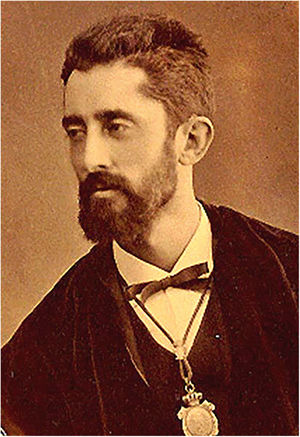

In 1880, Virchow decided to visit the Hospital de San Lazaro to corroborate some of his theories about leprosy.3 At that time, the hospital director was Dr. D. Benito Hernando y Espinosa (Fig. 6). In 1872, when he was 25 years of age, Hernando had been appointed to the Chair of Therapeutics in the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Granada, a position he held for 15 years. He was also Professor of Dermatology at the same university and, during the same period, occupied the post of Director at both the Hospital San Juan de Dios and the Hospital de la Lepra de San Lázaro. Since his appointment as Director of San Lázaro, he had been studying the medical records, autopsy findings, and statistical data of patients affected by leprosy, identifying several variants of the disease.4 He had also studied the many clinical manifestations, symptoms, and presentations of leprosy and the associated etiological, pathogenic, and prognostic factors.

During his journey to Granada, Virchow visited several other Spanish cities, including Madrid, where he was impressed by the Spanish National Museum of Painting and Sculpture (now the Prado Museum) and particularly by the Reina Isabel II room where the paintings of Velázquez were hung.

On 8 October 1880, Virchow arrived in Granada, where he took the opportunity to visit the Alhambra, the Palace of Charles V, and the Puerta del Perdón (Door of Forgiveness) in the Cathedral.5 He also enjoyed an evening stroll to appreciate the city's “Moorish aesthetics”.5

Virchow was very impressed with the Hospital de Leprosos de San Lázaro. In his own words: “In the plans for the construction of this hospital, the Catholic Monarchs incorporated all the contagious ideas of the Middle Ages, which today we look at again, seeing it as the most finished model of its kind in the world”.5

While Virchow did not speak Spanish, he communicated easily with everyone in the hospital through Greek and Latin. During his visit, Virchow confirmed some of his ideas about leprosy. In particular, among his anatomopathological observations he had predicted periods of remission and exacerbation of the neuralgic manifestations,4 a phenomenon that Hernando had often observed. Virchow also gave two brilliant lectures on two significant complications of leprosy: muscular atrophy and claw hands.5

References to Virchow's Work in Hernando's BookHernando published most of his observations in 1881 in a comprehensive book entitled De la lepra en Granada (On Leprosy in Granada) (Fig. 7). In the prologue, he mentioned the gift that the hospital had presented to Virchow6: “Dr. Virchow took from this Faculty fragments of elephantiasic organs and macroscopic preparations for his laboratory in Berlin, where he has studied them and sent me some very important ideas, which have served to guide me in the course of this work” (elephantiasis was one of the terms used at the time as a synonym for leprosy).7

In his book, Hernando makes several other references to Virchow's work. He highlights the fact that Virchow had taken the histologic study of leprosy to “a high level of perfection”.7 He also comments that Virchow's observations had “guided investigations that have since been carried out, and were the key that has unlocked a multitude of enigmas”.4 According to Hernando, Virchow's observations were so important in the study of the nervous system “that it can be said without reserve that without the aforementioned idea of this extraordinary man, no step in the symptomatology of the nerves could be taken today”.4

Regarding the debate about whether leprosy was an infectious disease, Hernando stated that “the disease is caused by the bacillus found in the lacerated organs”8 and “it is present in the cutaneous tubercles, mucous membranes, cornea, nerves, fibrocartilage of the epiglottis, thyroid and cricoid cartilages, lymph nodes, liver, and testicles”.9 He went on to explain: “The bacterium I am talking about produces the leprous tubercles once it is transported to a point”.7 This opinion was not shared by Virchow, who emphasized that “the tubercle is the lesion of leprosy”.7 The “tubercle” here refers to a tumor and, therefore, according to Virchow's theory of neoplasms, would have probably originated from leukocytes in peripheral blood.7

Hernando also describes the “empty spaces” that could be seen in the “protoplasm” of the infected cells, which had been described by Virchow.7

Nonetheless, Virchow's general view of leprosy was admired by Hernando, who wrote: “Virchow studies leprosy, proclaims the anatomical unity of the lesions observed in the organs of the lacerated patients and makes this part of science, thereby taking the new direction that has impressed all pathology”.7

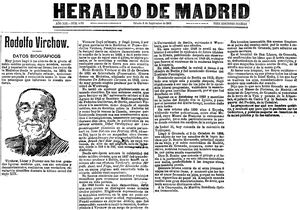

Virchow died on the 5th of September 1902. Three days later, a Spanish newspaper in Valencia called Las Provincias published the news of his death on its front page (Fig. 8).10 The following day, the same newspaper published 2 articles about Virchow (Fig. 9)—one with details of his funeral in Berlin,11 and the other alluding to an article that had been published in the newspaper El Heraldo de Madrid12 about Virchow's visit to Spain5 (Fig. 10).

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.