The differential diagnosis of facial edema and erythema is broad and includes diseases with variable outcome that may require urgent attention. We report 2 cases of patients in whom these clinical symptoms were signs of neoplastic disease.

The first patient is a 59-year-old woman with a past history of breast and lung cancer 6 years earlier, who presented palpebral and facial erythema and edema that had appeared 1 month earlier. The patient was being studied due to a probable angioedema and was receiving treatment with topical corticosteroids and antihistamines, with gradual worsening of the condition. The physical examination revealed an edema in the cervical region and upper chest, together with collateral circulation (Fig. 1). Computed tomography of the chest revealed an infiltrating mass enclosing and constricting the superior vena cava (Fig. 2). Subsequent studies confirmed a recurrence of the patient’s lung cancer.

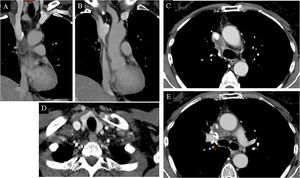

Computed tomography of the lungs in the first patient. Coronal (A and B) and axial (C-E) view of mediastinal window. An infiltrating mass can be seen, enclosing and constricting the superior vena cava from the arch of the azygos vein to where it enters the right atrium (yellow circles and arrows). Image D shows a hypodense diseased lymph node in the right supraclavicular fossa (arrow tip). Surgical clips from past right upper lobectomy (asterisk).

The second patient is a 69-year-old woman with a past history of allergic rhinitis, who visited the emergency department with a palpebral and facial edema that had appeared 15 days earlier. She had undergone treatment with oral corticosteroids and antihistamines due to suspected angioedema, with no response. She reported weight loss of 5 kg in 6 months and stated that she was a smoker. Physical examination revealed edema of the face and neck, and right jugular vein distention (Fig. 3). A chest x-ray showed a hilar mass causing complete atelectasis of the right upper lobe 1B). Computed tomography of the chest confirmed a mediastinal infiltrate and obstruction of the superior vena cava. Subsequent studies confirmed the diagnosis of lung cancer.

In superior vena cava syndrome (SVCS), vascular infiltration by a mass (most frequently tumor) obstructs venous flow to the right atrium and causes gradual edema of the face and upper extremities, and may be associated with reddening.1–3 Distention of veins in the torso and neck, which worsens in the supine position, makes it possible to differentiate it from other diseases. Imaging tests usually confirm the diagnosis.3 This is an entity in which signs on the skin may indicate an internal tumor, as also occurs with other cutaneous manifestations in the context of lung cancer.4

In the 2 patients described, the first diagnosis was angioedema, a sudden inflammation of the skin, subcutaneous tissue, or mucosa due to increased capillary permeability.5,6 Facial edema, however, usually persists for weeks and does not respond to antihistamines. It is not usually due to angioedema. Nevertheless, we have found this incorrect diagnosis of angioedema in SVCS repeated in the literature.7–9

Diagnostic failure in SVCS can lead to inappropriate treatment of the real disease, which may be severe in some cases, as in those reported here.

Other entities to consider in the differential diagnosis include dermatomyositis, which was another of the principal suspected diseases in the first case described and which was the reason for performing a skin biopsy and myositis antibody assay, with no findings. Heliotrope rash, shawl sign, and their potentially paraneoplastic nature may be similar to SVCS. But the other manifestations, such as myositis and Gottron papules, may help to differentiate it.

Other entities that should be considered due to their potential to cause facial erythema or edema include acute contact dermatitis, which typically affects the skin surface, and exanthema caused by drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS), in which skin involvement tends to be generalized. These and other diseases that rarely produce facial edema (such as rosacea, hypothyroidism, subcutaneous emphysema, orofacial granulomatosis, urticaria, hypocomplementemic vasculitis, systemic capillary leak syndrome, and histaminergic headache) must be considered in the differential diagnosis.3

In conclusion, we report 2 patients with SVCS secondary to a tumor, which illustrate the importance of considering this syndrome in the differential diagnosis of facial or cervical edema, in which a thorough patient history and complete examination are essential.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Tomás-Velázquez A, Quan López PL, Calvo Imirizaldu M, España Alonso A. Síndrome de vena cava superior. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2021;112:471–473.