Stewart-Bluefarb syndrome (SBS), also known as pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma, is a very rare subtype of angiodermatitis associated with congenital arteriovenous malformations (AVMs). We report a case of SBS and review the literature on this disease.

A 46-year-old man was referred to our unit for assessment of a painful, slow-growing ulcer on the lower right limb that had first appeared 3 months earlier. The patient had dyslipidemia and was an active smoker. The patient presented with raised, self-limiting brownish papular lesions that had recurred since childhood and had never been diagnosed. Physical examination revealed symmetrical, bilateral palpable pulses without bruit or thrill, raised brownish-violaceous tumors in the pretibial and outermost supramalleolar region, perilesional eczema, and an ulcer measuring 3×2cm with irregular borders, a fibrinous base, and mild signs of infection (Fig. 1), with no dysmetria of the lower limbs. Complete blood count, biochemistry, and serologic tests were negative or normal. Given the presence of atypical skin lesions, a complete Doppler ultrasound examination was performed on both limbs and a skin biopsy was carried out.

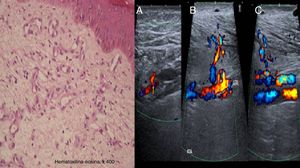

Histologic examination revealed the proliferation of capillaries in the deep dermis and papillary dermis, fibrosis, extravasated red blood cells, hemosiderin deposits, and tortuous vessels consistent with SBS. Doppler ultrasound confirmed the presence of underlying arteriovenous fistulas of the anterior and posterior tibial arteries with arterialized venous flow distal to the fistulas (Fig. 2).

On the left, a histologic image showing the proliferation of capillaries in the deep dermis and papillary dermis, fibrosis, extravasated red blood cells, hemosiderin deposits, and tortuous vessels. On the right, Doppler ultrasound images showing an arteriovenous fistula of the posterior tibial artery (A), anterior tibial artery (B), and arterialized venous flow distal to the anterior tibial vein (C).

Conservative treatment with 10 days of targeted antibiotic therapy was initiated after microbiologic culture detected the presence of Staphylococcus aureus. Compression therapy was also initiated with 2-in-1 compression stockings with a lateral zipper, as well as local wound care with a lipido-colloid dressing. At 3 months, the ulcer had healed and the pain had disappeared. The patient has continued to use compression therapy and remains asymptomatic after 1 year (Fig. 3).

Angiodermatitis is a group of angioproliferative diseases that manifest as skin lesions resembling Kaposi sarcoma.1–3 These entities consist of benign hyperplasia of preexisting vascular structures and can be associated with AVMs, as in the case of SBS.

SBS is a rare benign angioproliferative entity with histologic similarities to Kaposi sarcoma. It was first described by Earhart et al.4 in 1974 and fewer than 20 cases have been reported. SBS generally affects young men starting in the second decade of life5 and is characterized by progressive brown or violaceous maculopapular skin lesions and underlying AVMs. The lesions appear unilaterally on the lower limbs—on the dorsum of the foot, on the ankle, and on the calf—and are accompanied by edema, local temperature increase, soft-tissue hypertrophy, and varicose veins as a consequence of venous stasis.2,6 Complications can include ulcers and verrucous lesions.1,3

Differential diagnosis should include acroangiodermatitis of Mali, which typically appears in elderly patients as a consequence of chronic venous insufficiency and develops bilaterally, as well as Kaposi sarcoma, lichen planus, vasculitis, lymphoproliferative diseases characterized by congenital arteriovenous fistulas such as Klippel-Trenaunay-Weber syndrome, and iatrogenic diseases in patients who have hepatitis C or are undergoing dialysis.4,7,8 Various theories have been proposed regarding the etiology and pathogenesis of SBS; an increase in venous pressure resulting from AVM or ischemia caused by arteriovenous steal can stimulate the proliferation of endothelial cells.7

Suspicion of SBS is purely clinical (atypical venous lesions, soft-tissue hypertrophy, palpation of thrill, or auscultation of bruit) and diagnosis is confirmed by histology; it is therefore important that dermatologists be familiar with this rare disease.8 Histologically, SBS is characterized by the proliferation of endothelial cells, angiogenesis with a lobular pattern in the deep dermis and papillary dermis, and extravasated red blood cells, without fusiform neoplastic cells or proliferation independent of normal structures (features typical of Kaposi sarcoma).1,7 Doppler ultrasound can detect the presence of arteriovenous communications,2,3 although arteriography remains the gold standard1,7 for diagnosis and treatment.3,5

Treatment of SBS remains controversial. Most experts recommend conservative treatment8 and preventive treatment with compression stockings and limb elevation if edema is present.6 Symptomatic treatment of local complications is crucial,1 whereas specific treatment is rarely possible due to the presence of various distal communications.7,8 Surgery is indicated in patients with functional impotence, refractory pain, recurrent infection, bleeding, or cardiac decompensation.5,8 Amputation of the limb is sometimes the only option.9 Selective embolization with different particles, intravenous laser, radiofrequency ablation, and ultrasound-guided sclerotherapy can be alternatives in complex and symptomatic cases.5 A recent case report described the use of the glycosaminoglycan Cacipliq20 (heparin sulfate analogue) in a patient with SBS, with complete resolution of the ulcer.10

In conclusion, we have described a case of a rare syndrome of angiodermatitis that manifested as a chronic painful ulcer and skin lesions resembling Kaposi sarcoma, arising from an underlying arteriovenous communication. We have described a new vision for diagnosis using Doppler ultrasound and review the handful of studies on controversial therapeutic measures for this disease that have been published to date.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: García Blanco VE, Doiz Artázcoz E, Galera Martínez MC, Rodríguez Piñero M. Síndrome de Stewart-Bluefarb: caso clínico y revisión de la literatura. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2018;109:934–936.