The prognostic value of sentinel lymph node (SLN) biopsy findings and mitotic activity in melanoma has been confirmed in the literature, but the relation between them has not been well established.

ObjectivesThe main objective was to describe and analyze the correlation between SLN biopsy results and the mitotic rate in patients treated for melanoma in our hospital.

MethodsA total of 139 consecutive patients who underwent SLN biopsy between May 2001 and May 2009 were included. The relation between the mitotic rate and SLN status was analyzed with the χ2 test and the Fisher exact test.

ResultsThe correlation between the 2 variables was nonsignificant (P =.071) in the patient series overall, but a significant association was found in the subgroup of patients with tumors of Breslow thickness between 1 and 4mm (P =.034). The likelihood (odds ratio) of SLN positivity with a mitotic rate of less than 1 mitosis/mm2 in this subgroup was 0.838 (95% CI, 0.758-0.926).

ConclusionsOur findings support use of the mitotic rate to predict SLN status in melanoma tumors of intermediate thickness. Our study also shows the need for further investigation of the relation between these 2 variables in thin and thick tumors.

Diversos estudios han demostrado el valor pronóstico de la técnica de la biopsia del ganglio centinela (BGC) y el índice mitótico (IM) en el melanoma. Sin embargo, la relación entre ambos factores no está bien establecida.

ObjetivosEl objetivo principal del estudio es describir y analizar la relación entre el resultado de la BGC y el IM en los pacientes con melanoma atendidos en nuestro centro.

MétodoEn total se incluyeron 139 pacientes en los que se realizó la BGC de forma consecutiva entre mayo de 2001 y mayo de 2009. La relación entre el IM y el resultado de la BGC se ha realizado mediante el test χ2 y el test exacto de Fischer.

ResultadosSe detectó una correlación no significativa entre estas 2 variables con p=0,071. En el subgrupo de pacientes que tenían un espesor de Breslow entre 4 y 1mm el resultado fue una asociación estadísticamente significativa entre el IM y el resultado de la BGC con p=0,034. La odds ratio para tener un ganglio positivo teniendo un IM<1 en este subgrupo es de 0,838 (IC 95%: 0,758-0,926).

DiscusiónNuestro resultado apoya la utilización del IM como factor predictivo del resultado de la BGC en melanomas de espesor intermedio y apoya la necesidad de estudiar la relación entre estos factores para melanomas finos y gruesos.

Several studies have demonstrated that regional lymph node status is the most important independent prognostic factor for survival in melanoma.1–3 Although it has not been proven within the setting of a randomized clinical trial that the early removal of positive lymph nodes improves survival, it is accepted that accurate staging is the basis for establishing prognosis and making treatment decisions.2 The sentinel lymph node (SLN) biopsy technique was first described by Morton and colleagues in 1990.4,5 SLN biopsy is currently considered to be the most sensitive and specific technique for detecting melanoma micrometastases in regional lymph nodes, and furthermore, it is associated with lower morbidity and fewer adverse effects than elective lymphadenectomy.2,6–8 Mitotic rate is considered to be the second strongest predictor of survival in patients with primary melanoma, exceeded only by Breslow thickness.9 In the new 2009 American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging system, mitotic rate replaced Clark level as the second predictor of survival for melanomas with a thickness of 1 mm or less.7 Although mitotic rate is a discreet quantitative measure, with a minimal value of 0, no cutoff rates of higher than 1 mitosis/mm2 have been found to indicate an increased risk of melanoma.10 The relationship between SLN status and mitotic rate is not well established.11,12

We hypothesized that SLN status must be significantly correlated with mitotic rate and with other established prognostic factors used in melanoma.

ObjectivesThe main aim of this study was to describe and analyze the correlation between SLN status (positive or negative) and mitotic rate in patients with melanoma seen at our hospital. Secondary aims were to determine if node-positive patients had shorter survival than node-negative patients and if there was any correlation between a positive SLN biopsy and other established prognostic factors in melanoma, namely, Breslow thickness, Clark level, ulceration, regression, age, and sex.

MethodsStudy SettingThe study was performed in the dermatology department of Consorcio Hospital General Universitario de Valencia (CHGUV), Spain, a tertiary level hospital that serves a population of 378 138 inhabitants.

Study DesignWe performed an analytic cohort study with a longitudinal observational design in which data were collected retrospectively and prospectively.

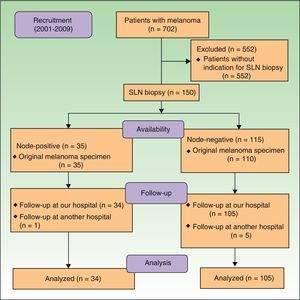

Study PopulationWe retrospectively selected patients diagnosed with melanoma who had undergone SLN biopsy between May 2001 (the year in which this technique was introduced in the CHGUV) and May 2009 (total of 150 patients) from the melanoma database in our hospital's dermatology department. In all cases, the clinical and histologic information was collected prospectively from biopsy samples taken at the time of diagnosis before the SLN biopsy. The inclusion criteria were a) a tumor thickness of 1 mm or more or of between 0.75 mm and 1 mm in the case of tumors with histologic signs of regression or ulceration; b) mitotic rate measured directly using the primary tumor biopsy specimen; c) an SLN biopsy at our hospital; and d) follow-up at our hospital. We excluded patients with multiple melanoma or extracutaneous melanoma, patients under 16 years of age, and patients for whom it was not possible to re-examine the original biopsy specimen (Fig. 1).

The original histology report was reviewed in 2011 by a dermatopathologist with experience in pigmented lesions; in accordance with the recommendations of current clinical guidelines, a single dermatopathologist was used to eliminate interobserver variability.7 Regression was considered to be present when an inflammatory infiltrate was observed in over 50% of the lesion, with accompanying fibrosis (even if this was less prominent). The dermatopathologist systematically recorded the following information: diagnosis, tumor thickness (Breslow thickness in mm), presence of ulceration, mitotic rate, margin involvement, depth of invasion (Clark level),7 histologic subtype, presence of regression, T stage, and presence of vertical growth.13

SLN Biopsy TechniqueSLN biopsy was performed following the preoperative intradermal injection of the radionuclide technetium 99 (Nancol, Molypharma, S.A.) in the peritumoral area on the day of the procedure, with detection by a gamma camera and subsequent gamma probe examination (Navigator GPS, Dynasil Corp.).

Histologic SLN AnalysisThe SLN was excised along the vascular pedicle and fixed in formalin. The tissue was then cut into 3-μm serial slices using a microtome; 3 slices of each block were stained with hematoxylin-eosin and 1 with Melan-A.3,14 All SLNs with any number of hematoxylin-eosin- or Melan-A-positive cells (Menarini Diagnostics S.R.L) (no minimum threshold) were classified as node-positive.

Follow-upAll the patients included in the study were followed, regardless of subsequent treatment We made a note of all instances of relapse, including distant metastasis, local recurrence, and regional nodal metastasis. We also recorded deaths due to melanoma or other causes. The follow-up period lasted to February 2012.

Statistical AnalysisAge, Breslow thickness, and mitotic rate were categorized for statistical analysis. The χ2 test and Fisher exact test were used to compare the clinical and histologic characteristics of node-positive and node-negative patients. To control for possible confounders, we performed stepwise logistic regression with an entry criterion of P<.20 for the initial model and a permanence criterion of P<.05 for the final model. Disease-free and overall survival were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method and the log-rank test was used to detect differences between groups. Multivariate survival analysis of disease-free and overall survival using the Cox regression model, with the incorporation of statistically significant variables detected by the log-rank test (P<.05), was used to investigate independent predictors of survival in the melanoma patients in our series. Individual covariates were expressed using the hazard ratio (HR) and corresponding 95% CI. The level of statistical significance was set at a P value of less than .05. Statistical analysis was performed using the IBM SPSS statistics package 20 for MAC.

ResultsSampleWe included 139 patients for whom it was possible to re-examine the biopsy specimen from the original tumor. Table 1 summarizes the clinical and epidemiological characteristics of the patients. Their mean (SD) age at the time of SLN biopsy was 53.34 (16.05) years (range, 18-85 years), and there was a slight predominance of men over women (n=77, 55.4% vs n=62, 44.6%).

Clinical and Epidemiological Characteristics of Study Population.a

| Male Patients | Female Patients | P Value | |

| Age group | .073 | ||

| ≤60 y | 59.7 (46) | 74.2 (46) | |

| >60 y | 40.3 (31) | 25.8 (16) | |

| Hair color | .307 | ||

| Blonde | 13 (10) | 24.2 (15) | |

| Red | 5.2 (4) | 4.8 (3) | |

| Brown | 81.8 (63) | 71 (44) | |

| Tumor site | <.001 | ||

| Head | 0 (0) | 3.2 (2) | |

| Trunk | 70.1 (54) | 25.8 (16) | |

| Upper limbs | 15.6 (12) | 22.6 (14) | |

| Lower limbs | 14.3 (11) | 48.4 (30) | |

SLN biopsy was positive in 24.5% of the sample (34 patients) and negative in 75.5% (105 patients). Tables 2 and 3 summarize the clinical and histologic characteristics of the patients according to whether they had a positive or negative SLN biopsy.

Clinical Characteristics of Patients According to SLN Status.

| SLN+ | SLN− | P Value | |

| Age group | .83 | ||

| ≤60 y | 23.9 (22) | 76.1 (70) | |

| >60 y | 25.5 (12) | 74.5 (35) | |

| Sex | .209 | ||

| Male | 28.6 (22) | 71.4 (55) | |

| Female | 19.4 (12) | 80.6 (50) | |

| Hair color | .017 | ||

| Blonde | 41.7 (10) | 58.3 (15) | |

| Red | 42.9 (3) | 57.1 (4) | |

| Brown | 18.7 (20) | 81.3 (87) | |

| Clinical type | .484 | ||

| LMM | 0 (0) | 100 (3) | |

| SSM | 21.3 (19) | 78.7 (70) | |

| NM | 32.1 (9) | 67.9 (19) | |

| ALM | 27.8 (5) | 72.2 (13) | |

| Other | 100 (1) | 0 (0) | |

| Preexisting lesion | .530 | ||

| Acquired MN | 19.4 (7) | 80.6 (29) | |

| Dyplastic NM | 0 (0) | 100 (2) | |

| Congenital NM | 0 (0) | 100 (2) | |

| No lesion | 27.3 (27) | 72.7 (72) | |

| Tumor site | .253 | ||

| Head | 0 (0) | 100 (2) | |

| Trunk | 31.4 (22) | 68.6 (48) | |

| Upper limbs | 19.2 (5) | 80.8 (21) | |

| Lower limbs | 17.1 (7) | 82.9 (34) | |

| Melanoma symptoms | |||

| Hemorrhage | .035 | ||

| Yes | 35.6 (16) | 64.4 (29) | |

| No | 19.1 (18) | 80.9 (76) | |

| Pain | .418 | ||

| Yes | 0 (0) | 100 (2) | |

| No | 24.8 (34) | 75.2 (103) | |

| Increased volume | .194 | ||

| Yes | 26.2 (32) | 73.8 (90) | |

| No | 11.8 (2) | 88.2 (15) | |

| Color changes | .464 | ||

| Yes | 28.3 (13) | 71.7 (33) | |

| No | 22.6 (21) | 77.4 (72) | |

Abbreviations: ALM, acral lentiginous melanoma; LMM, lentigo malignant melanoma; SLN, sentinel lymph node; NM, melanoma nodular; MN, melanocytic nevus; SSM, superficial spreading melanoma:

aData are expressed as percentage (number) of patients.

Histologic Characteristics of Patients According to Sentinel Lymph Node (SLN) Status.

| SLN+ | SLN− | P Value | |

| Clark level | .048 | ||

| iii | 17.4 (15) | 82.6 (71) | |

| iv | 36.6 (15) | 63.4 (26) | |

| v | 33.3 (4) | 66.7 (8) | |

| Breslow thickness | .044 | ||

| 0-2mm | 17.6 (13) | 82.4 (61) | |

| > 2mm | 32.3 (21) | 67.7 (44) | |

| Mitotic rate, mitosis/mm2 | .071 | ||

| <1/mm2 | 5.9 (1) | 94.1 (16) | |

| ≥1/mm2 | 27.0 (33) | 73 (89) | |

| Histologic ulceration | <.001 | ||

| Absent | 13.1 (13) | 86.9 (86) | |

| Present | 52.5 (21) | 47.5 (19) | |

| Regression | .909 | ||

| Present | 24.1 (13) | 75.9 (39) | |

| Absent | 25.0 (21) | 75.0 (64) | |

| Cell type | .840 | ||

| Spindle-shaped | 20 (1) | 80 (4) | |

| Epitheloid | 25.6 (22) | 74.4 (64) | |

| Mixed | 0 (0) | 100 (1) | |

| Nevoid | 0 (0) | 100 (3) | |

| Atypical | 23.8 (10) | 76.2 (32) | |

| Satellitosis | .554 | ||

| Absent | 23.4 (29) | 76.6 (95) | |

| Present | 30.8 (4) | 69.2 (9) | |

aData are expressed as percentage (number) of patients.

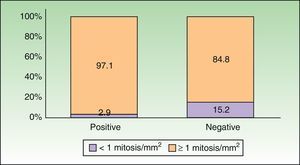

In total, 97.1% of the node-positive patients (n=33) had a mitotic rate of ≥1 mitosis/mm,2 and just 1 patient (2.9%) had a lower rate. In the node-negative group, 15.2% of patients (n=16) had a mitotic rate of <1 mitosis/mm2 and 84.8% (89 patients) had a rate ≥1 mitosis/mm2 (Fig. 2). Univariate analysis with the Fisher exact test showed a nonsignificant association between mitotic rate and SLN status (P=.071). In the subgroup of patients with a Breslow thickness of 1 to 4mm, however, we detected a statistically significant association between mitotic rate and SLN positivity (P=.034, Fisher exact test). In this subgroup, all the node-positive patients (n=25) had a mitotic rate of ≥1 mitosis/mm2 and none of the patients with a lower rate had a positive SLN biopsy. In the node-negative group, 16.2% of patients (n=12) had a mitotic rate of <1 mitosis/mm2 and 83.8% (n=62) had a rate of at least 1 mitosis/mm.2 The likelihood (odds ratio) of having a mitotic rate of <1 mitosis/mm2 and a positive SLN biopsy in the subgroup of patients with a Breslow thickness of 1 to 4mm was 0.838 (95% CI, 0.758-0.926).

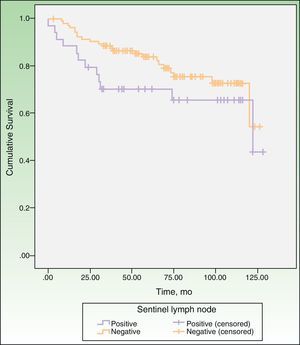

SLN Biopsy and SurvivalThe median overall survival in our series was 122 months and mean disease-free survival was 101.17 months (interquartile range, 93.59-108.75 months). The 5-year survival rate was 70.2% (95 CI, 54%-85%) in the node-positive group and 79% (95% CI, 70%-87%) in the node-negative group. Thirty-five patients died during follow-up and 3 experienced recurrence. As shown in Table 4, 12 of the patients who died were node-positive (35.3% of all node-positive patients) and 23 were node-negative (21.9% of all node-negative patients). The Kaplan-Meier curves show shorter overall survival in patients with a positive SLN biopsy, although the difference with node-negative patients was insignificant (P=.153, log-rank test) (Fig. 3).

Variables and Mortality in the Univariate Analysis.b

| Factor | No. of Deaths | % of Deaths | Survival, mo | 95% CI | P Valueb |

| Age group | .001c | ||||

| ≤ 60 y | 15 | 16.3 | 111.45 | 103.91-118.99 | |

| > 60 y | 20 | 42.6 | 80.04 | 64.88-95.22 | |

| Sex | .009c | ||||

| Male | 26 | 33.8 | 91.23 | 80.43-102.04 | |

| Female | 9 | 14.5 | 112.97 | 103.91-122.03 | |

| Ulceration | .002c | ||||

| Yes | 18 | 45 | 84.05 | 68.67-99.43 | |

| No | 17 | 17.2 | 107.38 | 99.44-115.32 | |

| Regression | .796 | ||||

| Yes | 13 | 25 | 98.67 | 85.98-11.36 | |

| No | 22 | 25.3 | 101.90 | 92.61-111.19 | |

| Breslow thickness | .007c | ||||

| 0-2 | 11 | 14.9 | 109.72 | 101.02-118.42 | |

| > 2 | 24 | 36.9 | 90.42 | 78.47-102.36 | |

| Clark level | <.001c | ||||

| iii | 18 | 20.9 | 104.73 | 95.25-114.22 | |

| iv | 9 | 22 | 103.77 | 92.82-114.72 | |

| v | 8 | 66.6 | 53.45 | 32.60-74.29 | |

| SLN status | .153 | ||||

| + | 12 | 35.3% | 91.03 | 73.78-108.28 | |

| − | 23 | 21.9% | 103.30 | 95.26-111.34 | |

| Mitotic rate, mitosis/mm2 | .230 | ||||

| <1 | 2 | 11.8 | 97.76 | 85.78-109.75 | |

| ≥1 | 33 | 27 | 99.42 | 91.18-107.67 | |

Abbreviation: SLN, sentinel lymph node.

a The event death is shown as total number and percentage. The mean time to event is expressed by average months and 95% CI.

Univariate analysis of the association between SLN status and established prognostic factors in melanoma patients showed a significant association for Breslow thickness (P=.044), Clark level (P=.048), and ulceration (P<.001). Regression (P=.909), sex (P=.209), and age (P=.88), were not significantly associated with SLN positivity (Tables 2 and 3). The only factor that retained its statistical significance in the multivariate analysis was presence of ulceration (P<.001), which was associated with a 7.039-fold increased likelihood of a positive SLN result (Table 5).

Multivariate Analysis of Establish Prognosis Factors and Sentinel Lymph Node (SLN) Status.

| SLN | P Value | Odds Ratio | 95% CI for Odds Ratio | |

| Lower Limit | Upper Limit | |||

| Breslow thickness | .721 | 0.823 | 0.284 | 2.388 |

| Clark level | .526 | 1.275 | 0.602 | 2.699 |

| Ulceration | <.001 | 7.039 | 2.681 | 18.482 |

| Regression | .864 | 1.083 | 0.435 | 2.700 |

| Mitotic rate | .145 | 5.062 | 0.572 | 44.837 |

| Age | .340 | 0.697 | 0.332 | 1.463 |

| Sex | .145 | 0.497 | 0.194 | 1.273 |

The indication for SLN biopsy in melanoma is based on studies that have demonstrated that SLN status is the most powerful independent predictor of overall and disease-free survival.15,16 However, there is no evidence that demonstrates that this technique actually has an impact on patient survival.17–19 Furthermore, it is associated with a morbidity of 10%, with complications including lymphedema, seroma, infection, and thrombophlebitis.20 Based on current indications, SLN biopsy is negative in 80% of patients who undergo the procedure. Our data are similar to those reported elsewhere: 24% of the patients in our series were node-positive, suggesting that both the selection criteria and detection and analysis methods we used were adequate. Apart from the morbidity associated with SLN biopsy, this procedure also incurs an additional cost that could be avoided in the 80% of patients with negative results if were possible to improve the selection criteria.19

Primary tumor mitotic rate has been shown to be a powerful independent predictor of survival in melanoma. Data from the AJCC Melanoma Staging Database show a negative correlation between increasing mitotic activity and survival. The AJCC has included a primary tumor mitotic rate of 1 mitosis/mm2 or higher as a major criterion for defining the T1b subcategory, but there are insufficient data with which to determine the risk of lymph node micrometastases in patients with this mitotic rate.6

In our series, most of the node-positive patients (97.1%) had a mitotic rate of at least 1 mitosis/mm2 but the differences with node-negative patients with the same mitotic activity (84.8%) were not significant. This lack of significance could have several explanations, such as the distribution or size of the sample or the threshold used for mitotic rate. We chose ≥1 mitosis/mm2 as this is the cutoff used by the AJCC for melanoma staging. A rate of ≥1 mitosis/mm2 has been found to correlate with survival but not with SLN biopsy results. Studies that have found a relationship between SLN biopsy and mitotic rate have used different thresholds for primary tumor thickness: 0-1 mitosis/mm2 (thin tumors), 2-5 mitoses/mm2 (intermediate-thickness tumors), and ≥ 5/mm2 and ≥ 6/mm2 (thick tumors).19,21,22 In our sample we included melanomas with a Breslow thickness of between 0.75mm and over 4mm. Mitotic rate has been reported to lose its predictive value with increasing tumor thickness and is considered a marker of aggressive disease only in thin tumors.21 Tumors with a Breslow thickness of less than 1mm have shown variable results in SLN biopsy.22,23

The subgroup analysis performed with patients with a Breslow thickness of between 1 and 4mm to control for possible confounders associated with thick tumors21 and to prevent bias resulting from the selection of thin tumors showed a statistically significant correlation between mitotic rate and SLN biopsy outcome (P=.034, Fisher exact test). The results of this subanalysis support the use of mitotic rate as a predictor of SLN biopsy results in melanomas of an intermediate thickness (1-4mm) and also highlight the need to further study the relationship between these 2 variables.23,24

SLN Biopsy and Other Established Prognostic FactorsApart from studying the relationship between SLN biopsy results and mitotic rate, we also analyzed the relationship between these results and other established prognostic factors in melanoma.6,7 The univariate analysis showed a significant association with increased Breslow thickness, Clark level, and the presence of ulceration, and a nonsignificant association with age, sex, and the presence of regression.

Breslow thickness is considered to be the main predictor of SLN biopsy outcome in melanoma and is used as the major criterion for determining whether or not SLN biopsy is indicated.6,7 SLN biopsy is recommended for tumors with a Breslow thickness of over 1mm, as these are associated with a risk of nodal involvement of over 10%. The risk falls to 3% for thinner tumors1–3 and SLN is only considered in such cases when there are additional negative prognostic factors. In our study, patients with a Breslow thickness of over 2mm had a significantly higher rate of lymph node metastases than those with thinner tumors in the univariate analysis (P=.044). We chose 2mm for this analysis as, statistically, it was the best cutoff for creating 2 groups. Our findings are consistent with those of other studies that have shown a relationship between increasing primary tumor thickness and the presence of lymph node metastases,12,16,25 although the thicknesses used in the analyses differed among studies.

Breslow thickness, which is recognized as one of the most reproducible predictive factors in melanoma,11,19,21,24,25 was not significant in our multivariate analysis. This could be because many histologic variables, such as Breslow thickness, Clark level, and ulceration are interrelated and may act as confounders.11

The prognostic value of Clark level for SLN positivity has been a topic of debate in other studies.11,19,21,22,24 In our series, we found a significant association between increased Clark level and a positive SLN biopsy in the univariate analysis (P=.048), but the fact that all the patients had a Clark level of at least III might have influenced the result. The cutoff used for Clark level in other studies is highly variable and it is therefore difficult to compare results. An optimum cutoff for predicting the presence of a positive SLN result based on Clark level has not yet been established.

The presence of ulceration in our study was significantly associated with a positive SLN result in both the univariate and multivariate analyses (P<.001). This association has been reported in numerous series,18,22 and ulceration has been found to be negatively correlated with survival in melanoma patients for all Breslow thickness subgroups.18 Accordingly, ulceration has been used in the AJCC melanoma TNM staging system since its sixth edition.9 In one study in which ulceration was not found to be associated with positive SLN status, the authors, Sondak et al.,11 suggested that this might be because of possible differences in the causes of ulceration and the fact that the presence of ulceration may lead to erroneous measurement of Breslow thickness. In our study, patients with a Breslow thickness of over 0.75mm and ulceration were referred for SLN biopsy, as is recommended by the AJCC.6 Our findings support the indication of SLN biopsy in patients with ulceration, even for tumors with a Breslow thickness of less than 1mm.

Age, sex, and regression were not significantly associated with SLN status in the univariate analysis. The predictive value of age in this respect is a topic of debate.11,19,21,24 Several authors have reported lower rates of nodal involvement in older patients, despite their having shorter overall and disease-free survival.11,26 These differences could be explained by age-related lymphatic dysfunction, as shown by Conway et al.,27 who reported a decrease in radiocolloid transit and uptake with increasing age. The relationship between sex and SLN biopsy results is not well established. While some studies have found a higher proportion of positive results in male patients,17,22 others have not.11,19,21,24 In our study, more men than women were node-positive (28.6% vs 19.4%), but the difference was not statistically significant.

Histologic regression is observed in 10% to 35% of all melanomas, but there is a lack of consensus on how regression is measured and on what cutoffs should be used.28 Tumor regression areas are composed of variable quantities of fibrous tissue, lymphocytes, new vessels, and melanophages replacing the primary melanoma. Regression measurements vary according to the definition of regression and on the subjective assessment of the dermatopathologist.28 In our series we did not find a significant relationship between regression and positive SLN status.

A positive SLN biopsy result is considered to be the most specific and sensitive prognostic factor for overall and disease-free survival in melanoma.2 In our study, the 5-year disease-free survival rate was 67% in node-positive patients and 82% in node-negative patients (nonsignificant difference, P=.132). The difference for 5-year overall survival was also nonsignificant (P=.153), with rates of 70.2% and 79% for patients with a positive and negative SLN result, respectively. Although our results show longer survival in node-negative than in node-positive patients, the differences are not statistically significance, but this could have several explanations. First, survival in patients with a positive SLN biopsy may have been influenced by subsequent treatment. According to the AJCC, the presence of nodal metastasis indicates stage III disease, the standard treatment for which is lymph node dissection. In our series, node-positive patients were considered to have advanced regional disease and, in some cases, were treated with adjuvant therapy such as high-dose interferon alfa. This difference in treatment may have influenced the lack of significant differences in overall and disease-free survival between patients with positive and negative SLN status. A second possible explanation is that our sample might have been too small to detect significant differences; we cannot rule out the possibility that significantly better survival might have been detected in node-negative patients in a larger sample. Tumor thickness might also have had a bearing on our results. Morton et al.3 found significant differences in survival among melanoma patients, but they analyzed a subgroup of patients with a tumor thickness of 1.2 to 3.5mm. The authors chose this cutoff because results from preliminary studies had indicated that lymphadenectomy performed electively or after the clinical detection of nodal involvement would affect survival in this subgroup of patients.29 Our results support the use of SLN biopsy for prognosis and staging in melanoma but additional studies are needed to investigate its therapeutic value.

ConclusionsThe relationship between mitotic rate and SLN status is not well established. Our results show that the 2 variables are not correlated in melanomas with a Breslow thickness of less than 1mm. We therefore agree with Attis and Vollmer30 that mitotic rate should not be routinely measured as it is a laborious procedure. We believe that for tumors thinner than 1mm, there are more useful factors, such as ulceration and depth of invasion, for selecting candidates for SLN biopsy. In thicker tumors, SLN biopsy is already indicated. In accordance with the recommendations of the sixth edition of the AJCC staging manual, we agree that mitotic rate should not be used to select candidates for SLN biopsy.

Ethical DisclosuresProtection of humans and animalsThe authors declare that no tests were carried out in humans or animals for the purpose of this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed their hospital's protocol on the publication of data concerning patients and that all patients included in the study have received sufficient information and have given their written informed consent to participate in the study.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no private patient data appear in this article.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Mahiques Santos L, Oliver Martinez V, Alegre de Miquel V. Biopsia de ganglio centinela en melanoma. Valor pronóstico y correlación con el índice mitótico. Experiencia en un hospital terciario. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2014;105:60–68.