The growing use of immunosuppressive agents in procedures such as kidney transplantation and in intensive polychemotherapy regimens for different types of cancer has led to a notable increase in opportunistic fungal infections.1,2Aspergillus species are ubiquitous, opportunistic, filamentous fungi often found in soil, decaying organic matter, and even in food remains.2 They tend to multiply in environments with high levels of dust dispersal and are particularly common in hospitals during building or maintenance work.2 Care should therefore be taken to protect immunocompromised patients or patients with a greater risk of infection from exposure to building work or damp environments. Aspergillus species can cause serious primary or secondary skin infections.3 We present a case of pustular cutaneous aspergillosis.

A 56-year-old man with type IgA multiple myeloma was evaluated for painless skin nodules measuring over 1cm and a large blister of recent onset on his left elbow. The patient had stage IIIA disease and had been under follow-up for 4 years. He had received several treatments, including 4 cycles of chemotherapy with bortezomib 1.3mg/m2 every 4 days, 4 cycles separated by a week of cyclophosphamide 500mg once a day for 3 days, and dexamethasone 40mg every 2 days for 12 days. He had also received radiation therapy and undergone hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Following a relapse in 2015, it was decided to attempt mini-allogenic transplantation with reduced-intensity FluMel-ATG conditioning (70mg/m2 melphalan, fludarabine 30mg/m2/d, bortezomib 1.3mg/m2, and anti-thymocyte globulin 2mg/m2) and an increase in melphalan infusion dose to 150mg/m2.

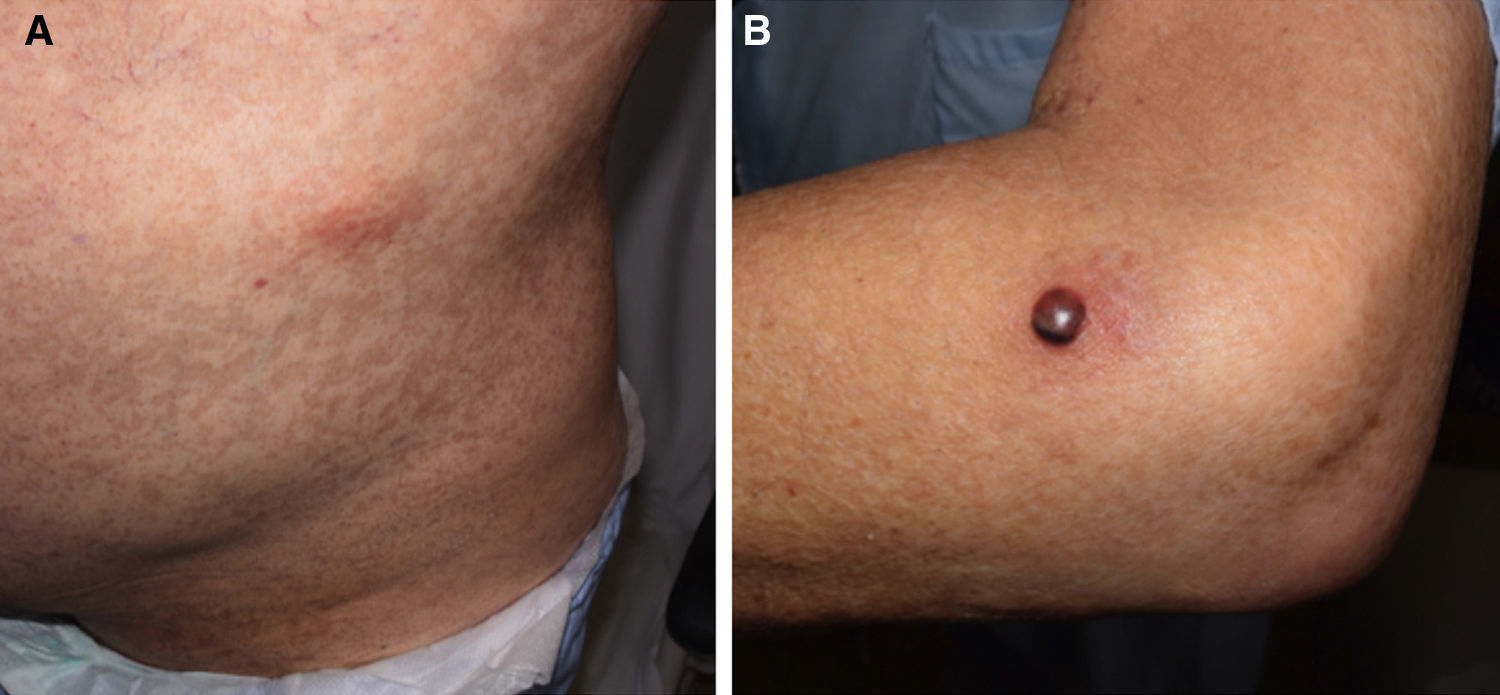

Forty days after the transplantation, the patient was evaluated by a dermatologist as he suddenly developed painless erythematous subcutaneous nodules measuring approximately 3cm on the anterior surface of both thighs and on the left abdominal flank (Fig. 1A). One of the lesions on the lateral surface of his left elbow was a tense 1.5-cm blister containing blood-stained pus with a fluid level (Fig. 1B). The patient reported no other symptoms. The onset of these lesions coincided with a progressive increase in serum galactomannan levels, which rose from previously undetectable levels to a level of 0.9.

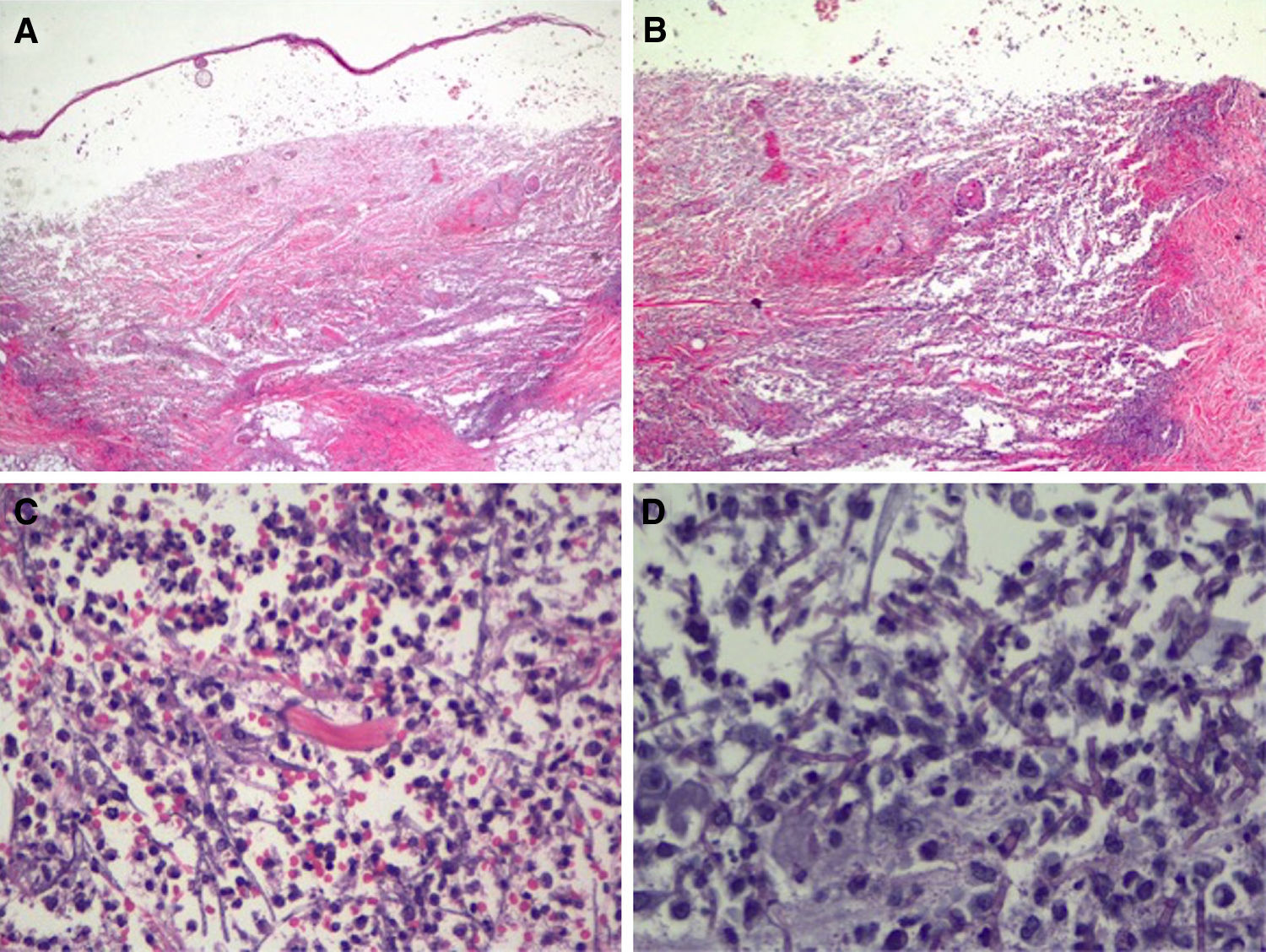

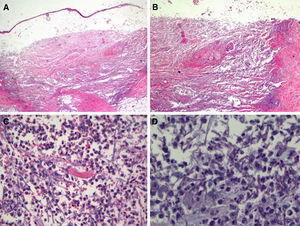

In view of the patient's condition and the general clinical picture, skin biopsy samples were taken for histology and microbial culture. Histologic examination of the elbow lesion showed a purulent subepidermal blister and an underlying infiltrate composed of abundant polymorphonuclear leukocytes that caused notable tissue destruction, with weakened structures, collagen bundles with an unstructured appearance, and effacement of adnexal structures (Fig. 2A). Higher magnification and periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) staining showed septate linear structures with dichotomous acute-angle (45°) branching throughout the dermis and extending into the more superficial areas of the subcutaneous tissue. These structures had an approximate diameter of 3μm and a length of up to 80μm in some sections and were consistent with hyalohyphomycosis (Fig. 2B). Culture in Sabouraud agar produced Aspergillus flavus, which was sensitive to voriconazole and echinocandins in the ETEST (Biomérieux).

Histologic features of the pustule following incisional biopsy. A, Large subepidermal blister with major underlying tissue destruction affecting the entire dermis and subcutaneous tissue (hematoxylin-eosin staining, original magnification ×20). B, Dense neutrophilic infiltration with destruction of dermal collagen and associated vasculitis (hematoxylin-eosin original magnification ×100). C, Detail showing dense neutrophil infiltration in the dermis and around barely perceivable filamentous structures (hematoxylin-eosin, original magnification ×200). D, Higher magnification and periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) staining showing septate linear structures with acute-angle branching consistent with the clinical and microbiologic diagnosis of cutaneous aspergillosis (PAS ×40, original magnification ×400).

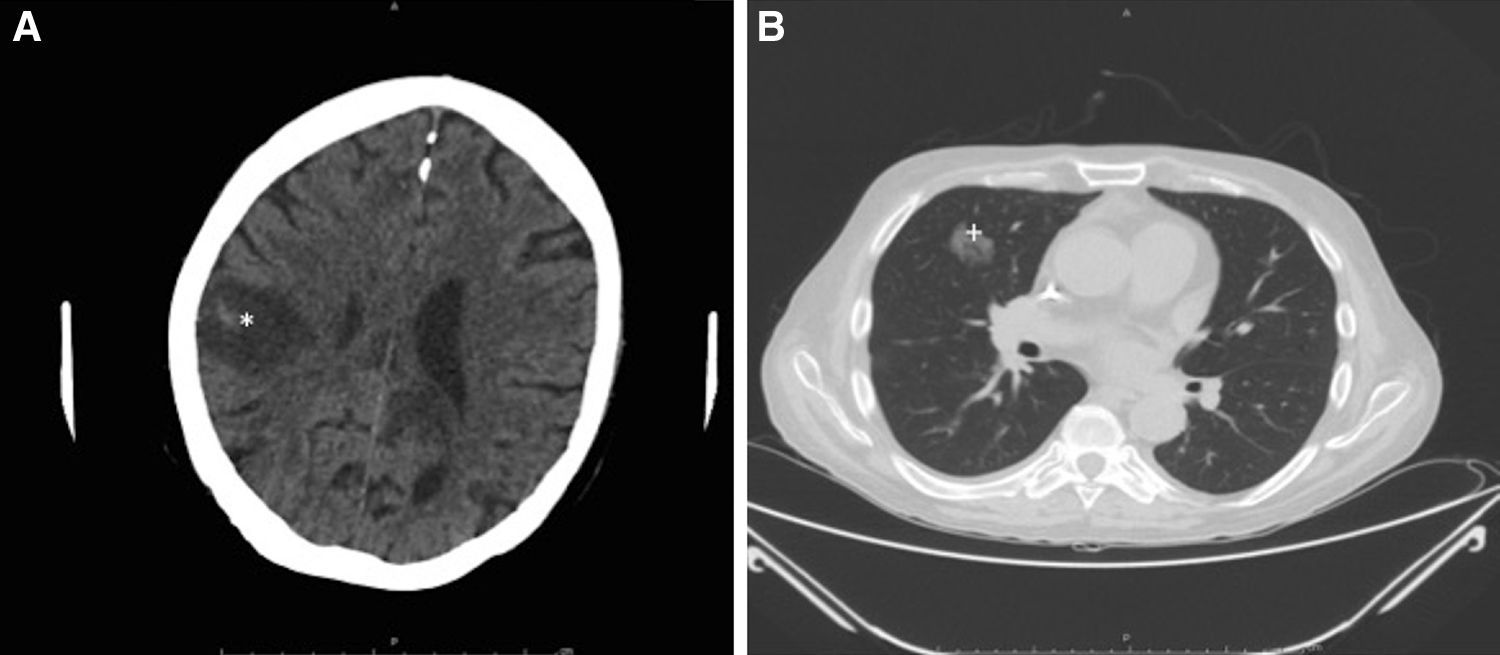

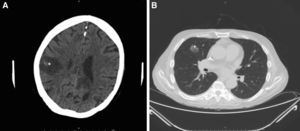

Intensive antifungal treatment was initiated with voriconazole (loading dose of 400mg followed by a maintenance dose of 200m/12h) and intravenous anidulafungin (loading dose of 200mg followed by 100mg/24h). Three days later, the patient developed right hemiparesis. In the staging study, the chest computed tomography (CT) scan showed previously undetected cavitated lesions in the right upper lobe of the lung (Fig. 3A). The brain CT scan showed 2 nonvascular frontal lesions consistent with a stroke secondary to infection (Fig. 3B). We decided to escalate the treatment to intravenous amphotericin B (400mg every 24h adjusted to the patient's weight). After 7 days, however, the patent developed severe dyspnea requiring oxygen support, aphasia, and general deterioration of health. A second brain scan showed multiple lesions similar to the lesions on the first scan but involving the entire brain parenchyma. The patient died as a result 2 days later. The family did not agree to an autopsy and we were therefore unable to collect brain tissue for microbiologic analysis.

Radiologic study after 3 days. A, Cranial computed tomography (CT) scan showing a nonvascular lesion in the right parasagittal-parietal region with internal spots of bleeding and a considerable intracranial mass consistent with cerebritis (*). B, CT scan of the chest area showing a cavitated nodule in the anterior segment of the right upper lobe, consistent with aspergilloma (+).

Aspergillus species are members of the eumycetes and are widely distributed in the environment. They are opportunistic pathogens that pose a particular threat to immunosuppressed individuals,2,3 particularly those with neutropenia.4 The most common species are Aspergillus fumigatus and A flavus.3Aspergillus species are ubiquitous in soil and vegetation.2 Although aspergillosis mainly affects the lungs,5 it can also affect the liver, brain, and skin.3 Between 5% and 27% of invasive aspergillosis cases involve the skin.3,6 Cutaneous aspergillosis can be primary or secondary,2,7 and these forms can be distinguished by the location and extension of lesions, which are widespread in secondary infections.2,3,7 Secondary cutaneous aspergillosis generally originates from the lungs,1 but it can also originate from the paranasal sinuses or the upper respiratory tract, although these forms are much less common. Primary aspergillosis is generally caused by direct skin inoculation through wounds from contaminated objects, intravenous lines1 at venipuncture sites on the arms, or even through dressings covering areas of macerated skin or catheters in patients requiring invasive procedures.8

Clinically, aspergillosis manifests as erythematous papules and macules that progress to nodules5 and eventually to ulcers with areas of central necrosis.3,7 Blisters are uncommon and may, as in our case, contain pus.4 Standard diagnostic procedures are the potassium hydroxide technique (or similar) and an incisional skin biopsy with sufficient depth.2,7 Histology shows septate hyphae measuring 3 to 5μm in diameter and 50 to 100μm in length, 45° branching, absence of blistering with PAS or Gomori methenamine silver stains, and abundant polymorphonuclear cells involving the entire wall, with angiocentric necrosis in many cases.4 Serum galactomannan levels should always be tested when aspergillosis is suspected.9 A progressive increase to a level over 0.5 in serial measurements points to a diagnosis of invasive bronchopulmonary or systemic aspergillosis, particularly in immunosuppressed patients.9Aspergillus infection is confirmed by polymerase chain reaction. Treatment consists of amphotericin B (5mg/kg/ 24h), combined with echinocandins (50-100mg/d) or voriconazole (200mg/12h).10 Debridement of necrotic lesions and rapid restoration of immunity are important.2,7

We have presented a case of pustular cutaneous aspergillosis in an immunosuppressed patient.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

We thank Dr Carmen Moreno from the Pathology Laboratory and the Radiodiagnostic Unit at Hospital Ramón y Cajal.

Please cite this article as: Fonda-Pascual P, Fernández-González P, Moreno-Arrones OM, Miguel-Gómez L. Aspergilosis cutánea secundaria pustulosa en paciente inmunosuprimido. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2018;109:287–290.