To analyze the triggers of atopic dermatitis (AD), adherence to medical recommendations, disease control, and health-related quality of life (HRQOL) from the patient's perspective.

Patients and methodsThis was a multicenter, cross-sectional, epidemiological study with the participation of adults (age >16 years; n=125) and children (age, 2-15 years, n=116). Patients had a history of at least 12 months of moderate to severe AD with a moderate to severe flare (Investigator Global Assessment score>2) at the time of recruitment. The Mann-Whitney U test was used to evaluate relationships between disease severity, determined according to the Scoring in Atopic Dermatitis index, and triggers reported by patients, adherence to recommendations and pharmacological therapy, HRQOL, and patient-perceived control.

ResultsThe most common triggers were cosmetic products, clothing, mites, detergents/soaps, and changes in temperature. In 47.2% of adults and 39.7% of children, pharmacological therapy was not initiated at flare onset. Adherence was highest to pharmacological therapy, skin moisturizing, and medical care recommendations. Disease control was considered insufficient by 41.6% of adults and 27.6% of pediatric patients and, in adults, this was associated with the severity of AD (P=.014).

ConclusionsThe therapeutic control of AD is susceptible to improvement, especially in adults. Although patients state that they follow medical recommendations, a significant percentage of patients do not apply recommended treatments correctly. Better education about the disease and its management would appear to be necessary to improve disease control and HRQOL.

Conocer, desde la perspectiva del paciente, los desencadenantes de la dermatitis atópica (DA), el grado de control percibido y el cumplimiento de las indicaciones médicas y su calidad de vida relacionada con la salud (CVRS).

Pacientes y métodosEstudio epidemiológico, transversal, multicéntrico incluyendo pacientes adultos (>16 años; n=125) y pediátricos (entre 2-15 años; n=116) con DA de intensidad moderada-grave, más de 12 meses de evolución y con episodios de lesiones activas moderados-graves (escala de evaluación global del investigador [IGA]>2). Se analizaron los desencadenantes informados por los pacientes, el cumplimiento de las recomendaciones y el tratamiento farmacológico (TF), las diferencias en CVRS y el control percibido (U de Mann-Whitney) según la gravedad de la DA (índice SCORAD-SCORing Atopic Dermatitis).

ResultadosLos desencadenantes más frecuentes fueron: cosméticos, ropa, ácaros, detergentes/jabones y cambios de temperatura. El 47,2% de los pacientes adultos y el 39,7% de los pediátricos no aplicaban el TF desde el inicio del episodio. El TF, la hidratación y los consejos médicos de cuidado fueron las recomendaciones más seguidas. El 41,6 y el 27,6% (adultos y pediátricos, respectivamente) consideraba que su grado de control era insuficiente y se asoció con la gravedad de la DA en adultos (p=0,014).

ConclusionesEl grado de control actual de la DA es mejorable, especialmente en adultos. Aunque los pacientes indican seguir las recomendaciones médicas, un porcentaje significativo no aplica correctamente los tratamientos. Parece necesario potenciar la educación sobre la enfermedad y su manejo para mejorar el grado de control y potenciar su CVRS.

Atopic dermatitis (AD), or atopic eczema, is a chronic inflammatory skin disease that appears in early childhood and affects between 7% and 20% of children and between 2% and 7% of adults.1–3 Although there is evidence of great geographical variability, it appears that the incidence and prevalence of this disease have increased in recent years.3,4 The symptoms of AD are intense pruritus, dry skin, and skin lesions that appear in acute episodes of exacerbation, or flares.5,6 Because of its clinical manifestations, in many cases AD has a negative impact on the patient‘s health-related quality of life (HRQOL).7–9 In children, specifically, AD can interfere with sleep and impair performance in school and leisure activities, with the resulting consequences for patients’ personal, family, and social lives.7

The etiology of AD has been linked to genetic, biological, immunologic, and environmental factors.5,6,10 The most common gene changes associated with AD are mutations in the gene encoding filaggrin.11 In response to this etiologic complexity, a comprehensive theoretical model has been proposed that describes genetic deficiency in epithelial cells and the resulting epidermal barrier dysfunction as a predisposing factor for AD.5 This process would be exacerbated by the presence of allergens that increase immunoglobulin E (IgE) sensitization, causing the immune system to become hypersensitized. This hypersensitization would favor the persistence of underlying subclinical inflammation, which, in turn, would facilitate the appearance of new AD flares. Geographical differences in the prevalence of AD suggest that other environmental factors—related to climate3,4 and pollution1—also play a role. In addition to these factors, the occurrence of flares has also been associated with articles of clothing, the presence of mites and dust in the home, cosmetics, certain foods, dietary changes, physiological stressors (infections, sweat, etc.), and emotional stressors (psychological stress).12–14

These possible triggers were analyzed in an observational study that included 4243 children with AD under the age of 14 years and 978 controls matched for age and sex.15 The study found that colder climates (Cantabrian and continental areas of the Iberian Peninsula) were associated with a greater number of flares. The most common flare triggers were changes in climate (reported by 64% of patients), followed by stress in the patients (26%), and personal hygiene products (21%), while stress in the parents (16%), dietary changes (15%), and changes in household cleaning products (4%) were less frequent.

Because multiple factors play a role in AD, the optimal approach to treating the disease requires patient and parent education as well as the active participation of the physician.6,10 In this study, we aimed to describe the triggers that patients with moderate to severe AD perceive as having the largest influence on the exacerbation of the disease and the patient-reported degree of adherence to medical recommendations. We also evaluated the degree of disease control perceived by patients and dermatologists and the impact of the disease on HRQOL in order to obtain a picture of the real situation currently faced by patients with moderate to severe AD.

Patients and MethodsThis was a multicenter, cross-sectional, epidemiologic study involving 30 dermatologists in various Spanish autonomous communities. Each dermatologist consecutively enrolled the first 5 patients he or she saw who met the inclusion criteria. Data were collected for children (aged 2-15 years) and adults (aged 16 years or older) who had been clinically diagnosed with moderate to severe AD according to the clinical judgment of the dermatologist. (Patients with a diagnosis of mild AD were excluded from the study.) Patients enrolled in the study had a disease duration of at least 12 months and, at the time of consultation, had an AD flare of moderate to severe intensity according to defined clinical criteria (Investigator‘s Global Assessment [IGA] score>2). The patients (or their legal guardians, in the case of children) were required to give written informed consent before being enrolled in the study. The study protocol was approved by the clinical research ethics committee of Hospital 12 de Octubre, and the study was conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practice guidelines and the Declaration of Helsinki and subsequent amendments.

Study Variables and Measurement ToolsUsing information collected from the patients’ medical records, the researchers described the therapeutic approach to AD used in each case and recorded the basic clinical variables of interest. They also assessed the severity of the flares at the time of consultation and estimated the degree of disease control achieved. The following instruments were used to assess the impact of the disease on each patient:

- 1.

SCORing Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD).16 This index is the most widely used instrument for assessing the severity of AD. It considers the extent and intensity of the lesions, as well as symptoms of the disease (pruritus and insomnia):

- -

Extent (A): The body surface area is divided into 4 segments (head and neck, trunk, upper limbs, and lower limbs). A percentage is assigned to each segment as a function of the extent of the lesions.

- -

Intensity (B): The clinical signs assessed are erythema, edema/papulation, oozing/crusting, lichenification, and dryness. A value is assigned according to the intensity of each sign: 0 (absent), 1 (mild), 2 (moderate), or 3 (severe).

- -

Subjective symptoms (C): On a visual scale of 0 to 10, the patient assesses the severity of pruritus and insomnia.

A total score is obtained with the following algorithm: SCORAD=A/5+7B/2+C. On the basis of this score, disease severity is classified as mild (0-14 points), moderate (15-40 points), or severe (>40 points).

- -

- 2.

Investigator's Global Assessment (IGA).17 This 6-category ordinal scale is used to assess the severity of lesions. The scale ranges from 0 (no inflammatory signs of AD and no lesions) to 5 (very severe erythema and/or papulation/infiltration).

- 3.

Clinical Global Impression–Severity (CGI-S).18 This scale consists of a single item that assesses disease severity on the basis of the physician's clinical judgment using an 8-point Likert-type scale ranging from 0 (not assessed) to 7 (among the most extremely ill patients).

- 4.

Assessment of degree of disease control achieved. The dermatologists ranked the degree of control achieved in each case on a 6-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (excellent control of AD) to 6 (very poor or very inadequate control).

With the participation of the patients (in collaboration with the parents or guardians, in the case of children aged 2 to 15 years) the researchers recorded the factors that the patients recognized as the most important triggers of flares. Patients were asked to choose factors from a complete list of triggers that have appeared in the scientific literature: perfumes or other toiletries containing alcohol, inappropriate detergents or soaps, contact with animals, household cleaning products, articles of clothing, presence of mites and airborne allergens in the home and furniture, bacterial infection, sweating, stress, changes in temperature, and particular foods (specified by the patient).

After selecting the perceived triggers, patients also indicated how often they followed medical recommendations for AD control on a 6-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (always) to 6 (rarely or never). The scale included the recommendations usually highlighted in patient education on AD control6,10,19:

- -

Skin hydration and use of moisturizing creams and emollients.

- -

Correct application of prescribed pharmacotherapies.

- -

Use of appropriate cleaning agents or soaps.

- -

Avoidance of sudden changes in temperature.

- -

Dietary recommendations and avoidance of certain potentially allergenic foods.

The same 6-point Likert-type scale used by the researchers was also used by the patients (or their legal guardians, in the case of children under the age of 16 years) to assess the degree of disease control achieved. Finally, to assess the impact of AD severity on their HRQOL, patients used the Atopic Dermatitis Impact Scale (ADIS), a specific instrument for assessing HRQOL in AD that has different versions for adults and children.8 The ADIS is a short, self-administered, previously validated questionnaire8,20 that has 9 items in the adult version and 8 items in the children's version. Respondents chose from 4 possible answers and their overall scores for each version of the questionnaire were linearly transformed into a scale of 0 (minimum impact on HRQOL) to 10 (maximum impact). In the case of children, the ADIS questionnaire (children's version) was completed by the parents or guardians.

Statistical AnalysisWe carried out a descriptive analysis of the patients’ clinical and sociodemographic characteristics, the triggers and precipitating events associated with the exacerbation of AD and the appearance of the current flare, the perceived degree of disease control, and adherence to medical recommendations (frequencies and percentages for qualitative variables and measures of central tendency for quantitative variables). Using the Mann-Whitney U test, we analyzed the differences in the scores for perceived disease control and impact on HRQOL as a function of AD severity, measured with the SCORAD index (mild or moderate vs severe).

To establish the size of the patient sample, we considered a proportion of moderate to severe cases among patients diagnosed with AD of 2.1:1.21 We estimated that, in order carry out a 1-sided test of the differences in means between the severity and control variables of the 2 independent groups (moderate vs severe) with a 95% CI and a statistical power (1-β) of 0.80, we needed to have 116 cases per group (adults and children) in order to find differences of moderate effect size (d=0.5). Data quality control and statistical analysis were performed with the SPSS statistical package (version 15.0).

ResultsIn the adult group (n=135), 10 patients were excluded because their disease severity at the time of consultation was mild according to the IGA scale. In the children's group, a total of 148 patients were initially enrolled in the study. After reviewing the inclusion criteria, we excluded 32 patients because their disease severity at the time of consultation was mild (n=7) or because they had been diagnosed with AD less than 12 months earlier (n=25). As a result, the study included 125 adults and 116 children, close to 50% of whom were female (Table 1) and all of whom had a moderate to severe flare (IGA>2).

Description of Patient Sample.

| Qualitative Variables | % of Adults (n=125) | % of Children (n=116) |

| Male patients | 49.6 | 50.0 |

| AD severity according to patient records | ||

| Moderate | 72.8 | 70.7 |

| Severe | 24.8 | 25.0 |

| Past history associated with risk of AD | ||

| Rhinitis | 29.6 | 33.6 |

| Asthma | 26.4 | 28.4 |

| AD | 24 | 28.4 |

| None of the above | 37.6 | 29.3 |

| Other | 8.0 | 12.1 |

| SCORAD score at the time of consultation | ||

| Mild | 7.2 | 6.0 |

| Moderate | 47.2 | 59.5 |

| Severe | 45.6 | 34.5 |

| Application of pharmacotherapies | ||

| Starting the day of onset | 38.4 | 37.9 |

| Within 3 days | 15.2 | 13.8 |

| Within 1 week | 18.4 | 13.8 |

| After 1 week | 13.6 | 12.1 |

| CGI-S scale | ||

| Markedly or severely ill | 62.4 | 50.9 |

| IGA scale | ||

| Moderate erythema | 49.6 | 53.4 |

| Quantitative Variables | AdultsMean (SD)n=125 | ChildrenMean (SD)n=116 |

| Age | 33.4 (13.54) | 7.71 (3.93) |

| Disease duration, mo | 239.08 (19.9) | 68.72 (5.72) |

| Time since last flare, d | 81.82 (119.39) | 76.41 (113.71) |

| Dermatologist visits in the past year | 4.30 (3.46) | 3.39 (2.94) |

| ADIS score | 3.77 (2.04) | 2.86 (1.84) |

Abbreviations: AD, atopic dermatitis; ADIS, Atopic Dermatitis Impact Scale; CGI-S, Clinical Global Impression–Severity; IGA, Investigator's Global Assessment.

At the time of diagnosis, 72.8% of adults and 70.7% of children were diagnosed with moderate AD. At the time of consultation, nearly 50% of adults and 53.4% of children had moderate erythema according to the IGA scale. SCORAD results showed that most patients—both adults and children—had moderate to severe AD at the time of consultation (Table 1). Although patients were included in the study only if they presented erythema and/or papulation of at least moderate intensity (IGA>2), 7.2% of adults and 6.0% of children had a SCORAD result of less than 15 points. According to the CGI-S values assigned by the dermatologists, nearly 58% of adults were moderately ill and 5% were severely ill (figures consistent with the results of the specific tests) while 47.5% of children were markedly ill and 5.2% were severely ill (Table 1).

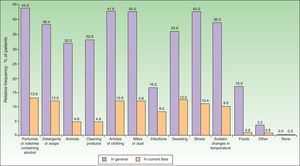

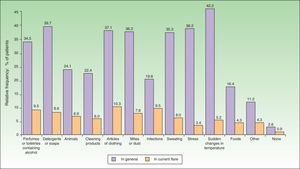

The most common factors perceived by patients as triggers of flares (Figs. 1 and 2) were perfumes and personal hygiene products (44% of adults, 34.5% of children), articles of clothing (41.6% of adults, 37.1% of children), presence of mites or dust in the home (40% of adults, 36.2% of children), sudden changes in temperature (36% of adults, 42.2% of children), and stress (40% of adults, 36.2% of children). In adults, the foods most frequently perceived as triggers were sweets (3.88%), seafood (2.33%), and eggs (2.33%); in children, eggs (7.63%) and fish (3.05%) were the most common.

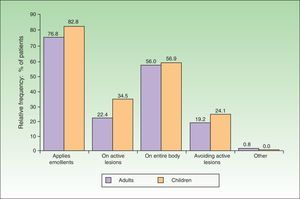

In 76.8% of adults and 82.8% of children, emollients were the therapeutic approach of choice during the flare (Fig. 3). The emollient was applied directly on the lesions in 22.4% of adults and 34.5% of children. In contrast, 19.2% of adults and 24.1% of children avoided active lesions when applying the emollient. Topical pharmacotherapy was used by 84.8% of adults and 77.6% of children. However, at least 13.6% of adults and 17.2% of children were not using any topical pharmacotherapy at the time of consultation, even though there was no difference in disease severity (as measured by the SCORAD index) between these patients and those who were using topical pharmacotherapy. The differences in SCORAD scores (mean [SD]) between treated adults (49.12 [20.86]) and untreated adults (48.72 [15.51]) and between treated children (43.44 -[9.88]) and untreated children (46.42 [14.67]) were not statistically significant (Mann-Whitney U test, P>.1in both comparisons).

Corticosteroids were the most frequently recommended topical treatment (72% of adults and 85.3% of children). Calcineurin inhibitors were used by 59.2% of adults and 47.4% of children. Antihistamines were taken by 59.2% of adults and 51.7% of children. Maintenance pharmacotherapy was used for disease control by 47.2% of adults and 49.15% of children.

As for adherence to administration recommendations, pharmacotherapy was first applied on the day the symptoms appeared in 38.4% of adults and 37.9% of children. Pharmacotherapy was initiated within 3 days of the appearance of symptoms in 15.2% of adults and 13.8% of children and even later—within the first week—in 18.4% of adults and 13.8% of children. In fact, more than a week elapsed before pharmacotherapy was started in 13.6% of adults and 12.1% of children. According to these findings, no treatment was initiated at the onset of the flare in 47.2% of adults and 39.7% of children. An additional 13.6% of adults and 17.2% of children had not applied any topical pharmacotherapy, despite the presence of a moderate to severe flare.

A majority of patients declared that they adhered to the following medical recommendations: application of pharmacotherapy, skin moisturizing, and the use of special soaps for their skin type (Table 2). The recommendations followed least often by the patients in their daily lives were avoidance of sudden changes in temperature and dietary advice.

Adherence to Medical Recommendations for the Control of Atopic Dermatitis.

| Medical Recommendations for the Control of Atopic Dermatitis | % of Adults (n=125) | % of Children (n=116) | ||||||||||

| Always | Nearly Always | Frequently | Sometimes | Occasionally | Rarely or Never | Always | Nearly Always | Frequently | Sometimes | Occasionally | Rarely or Never | |

| Pharmacotherapy | 35.2 | 40.0 | 12.8 | 8.8 | 2.4 | 0.0 | 47.4 | 35.3 | 5.2 | 2.6 | 5.2 | 0.9 |

| Skin moisturizing | 31.2 | 33.6 | 11.2 | 12.0 | 9.6 | 1.6 | 46.6 | 31.0 | 9.5 | 4.3 | 4.3 | 0.9 |

| Special soaps | 26.4 | 24.8 | 16.0 | 16.8 | 7.2 | 8.0 | 40.5 | 27.6 | 7.8 | 14.7 | 4.3 | 1.7 |

| Avoidance of extreme temperatures | 6.4 | 15.2 | 22.4 | 23.2 | 16.8 | 15.2 | 8.6 | 27.6 | 14.7 | 22.4 | 14.7 | 7.8 |

| Dietary recommendations | 8.8 | 17.6 | 12.8 | 16.0 | 19.2 | 23.2 | 30.2 | 20.7 | 8.6 | 7.8 | 9.5 | 12.9 |

Disease control was seen as insufficient or worse in a large percentage of cases (Table 3). The dermatologists rated the degree of disease control as excellent, good, or sufficient in only 38.4% of adults and 40.5% of children. From the patients’ perspective, disease control was excellent, good, or sufficient in 55.2% of adults and 67.2% of children.

Control of Atopic Dermatitis: Patient and Specialist Perspectives.

| Degree of Control in Adults, % of responses (n=125) | Degree of Control in Children, % of responses (n=116) | |||

| Dermatologist's Assessment | Patient's Assessment | Dermatologist's Assessment | Patient's Assessment | |

| Excellent | 1.6 | 5.6 | 3.4 | 12.9 |

| Good | 12.0 | 26.4 | 16.4 | 37.1 |

| Sufficient | 24.8 | 23.2 | 20.7 | 17.2 |

| Insufficient | 42.4 | 28.0 | 33.6 | 24.1 |

| Poor | 12.0 | 8.8 | 14.7 | 2.6 |

| Very poor or none | 4.0 | 4.8 | 2.6 | 0.9 |

In adults, significant differences were found in perceived disease control and HRQOL as a function of symptom severity at the time of consultation (mild or moderate vs severe SCORAD scores) (P<.01; Table 4). In children, differences in these variables were also present in the same direction, but they were only significant in the case of HRQOL (Table 4). Moods and personal and social performance were affected in some patients in both groups, as reflected in the total scores on the various scales used to assess HRQOL (Table 5).

Differences in Health-Related Quality of Life and Perceived Disease Control by Symptom Severity at the Time of Consultation.

| Group | Variable | SCORAD Score | No. of Patients | Mean Score | SD | P Valuea |

| Adults | Overall ADIS score | Mild or moderate | 68 | 3.09 | 1.82 | 0.001 |

| Severe | 57 | 4.58 | 2.02 | |||

| Degree of control | Mild or moderate | 67 | 2.97 | 1.11 | 0.014 | |

| Severe | 54 | 3.56 | 1.34 | |||

| Children | Overall ADIS score | Mild or moderate | 76 | 2.59 | 1.74 | 0.029 |

| Severe | 40 | 3.37 | 1.94 | |||

| Degree of control | Mild or moderate | 71 | 2.54 | 1.01 | 0.153 | |

| Severe | 39 | 2.92 | 1.31 |

Abbreviations: ADIS, Atopic Dermatitis Impact Scale; SCORAD, SCORing Atopic Dermatitis.

Perception of the Impact of Atopic Dermatitis on Patients’ Lives, by Study Group.

| Atopic Dermatitis Impact Scale | % of Adults (n=125) | % of Children (n=116) | ||||||

| Not at All | Somewhat | Quite a Bit | A Lot | Not at All | Somewhat | Quite a Bit | A Lot | |

| Feels sad or depressed | 33.6 | 48.0 | 16.0 | 1.6 | 50.0 | 31.0 | 8.6 | 2.6 |

| Feels tired | 28.8 | 35.2 | 28.8 | 6.4 | 39.7 | 31.0 | 17.2 | 4.3 |

| Feels irritable | 20.0 | 37.6 | 32.0 | 8.8 | 10.3 | 37.1 | 33.6 | 12.1 |

| Feels worried about his/her physical appearance | 17.6 | 23.2 | 38.4 | 20.0 | 41.4 | 22.4 | 19.8 | 6.9 |

| Feels powerless to control the disease | 6.4 | 34.4 | 33.6 | 21.6 | 24.1 | 19.0 | 17.2 | 8.6 |

| Feels uncomfortable at work or school | 59.2 | 22.4 | 11.2 | 4.0 | 57.8 | 17.2 | 11.2 | 1.7 |

| Limits social activities | 38.4 | 34.4 | 20.0 | 5.6 | 56.0 | 20.7 | 13.8 | 0.0 |

| Limits leisure activities | 16.8 | 36.8 | 31.2 | 12.8 | 41.4 | 32.8 | 11.2 | 5.2 |

| Limits relations with partner | 54.4 | 28.8 | 9.6 | 4.0 | – | – | – | – |

In recent years, a generalized consensus has emerged in leading scientific publications that AD is a disease of multifactorial etiology that requires a multifactorial, individualized approach in order to strengthen the effectiveness of the overall treatment.6,10 Therefore, during flares, topical moisturizing treatment and the avoidance of patient-specific trigger factors should therefore be recommended in addition to various pharmacological disease-control strategies such as topical corticosteroids. As an alternative to corticosteroids, anti-inflammatory treatments based on topical calcineurin inhibitors are very important in the treatment of flares; they also allow a proactive treatment approach that reduces the number of flares and increases flare-free time.22,23 Antibiotics for microbial infections, phototherapy, dietary recommendations, psychological care to reduce stress, and educational programs round out the clinical arsenal currently used to manage AD.

Educational programs for patients and caregivers generally focus on raising awareness about the chronicity and unpredictable course of AD, describe the important role of the epidermal barrier, and highlight the importance of the multidisciplinary approach followed by healthcare professionals in order to optimize long-term disease control.19,24 These programs usually stress the importance of skin care adapted to the needs of patients with AD and avoidance of specific triggers. They also include psychological counseling aimed at helping patients to manage stress, control the itching-scratching cycle, and cope with the disease. Although there have been exceptions, educational programs have generally succeeded at improving doctor-patient relationships, adherence, and HRQOL of patients and their families.24–26 In any case, these experiences show that the patient's attitude and motivation are extremely important for the control of AD because they influence adherence to the physician's prevention and treatment indications. This is why, in the present study, we chose to focus on the perspective of the patients, including the exogenous or environmental factors that they believe trigger flares, their attitudes towards treatment, their adherence to recommendations, and their perceived degree of disease control.

The main perceived trigger factors were cosmetics, articles of clothing, airborne allergens, stress, and sudden changes in temperature. These are the same factors that have generally been reported in the scientific literature.15 However, diet was not identified as an exacerbating factor in the current flare, despite the fact that it should be considered as a possible trigger. It is possible that patients did not mention diet because they habitually avoid certain foods—although food avoidance is not the most strictly followed indication, especially among adults—or because they perceive foods as having no exacerbating effect (as has been found in adolescents).27 Another possible explanation is the fact that we excluded patients under age 2 years, a group in which dietary recommendations could have a larger role.

Although most patients reported a high degree of adherence to medical recommendations—especially with regard to skin moisturizing, the use of special soaps, and the application of topical pharmacotherapies—deficiencies were observed in the application of emollients and pharmacotherapies. Emollients were not used to moisturize the skin in 23.2% of adults and 17.2% of children. In addition, between 15% and 23% of adults and children applied no pharmacotherapy whatsoever, even though they had a flare of at least moderate severity and a mean disease duration of 239.08 and 68.72 months, respectively. In addition, only 38.4% of adults and 37.9% of children started using topical agents on the first day the symptoms appeared. It would be interesting to determine the reasons for the patients’ treatment adherence problems, which are consistent with the results of earlier studies.21,28 These problems may reflect the patients’ fear of adverse effects, ignorance regarding proper application, and lack of information about the safety of the treatments.8,21,28,29

Finally, the degree of disease control was considered to be insufficient or worse by most dermatologists and a large percentage of patients (41.6% of adults and 27.6% of children). In this regard, the situation in Spain does not appear to have improved since 2006, when the study by Zuberbier et al.,21 was published.

The chief limitation of our study was its cross-sectional design, which prevented us from analyzing in detail the relationship between adherence and disease control, or changes in these variables and HRQOL, for example, when a flare is not present. However, we were interested in analyzing adherence to recommendations and disease control at the time of consultation for a flare, which is precisely when higher adherence rates would be expected.30 Another limitation of the study was the exclusion of children less than 2 years of age. Because of this, we were unable to analyze triggers or adherence to medical recommendations in that group of patients.

It is clear that much work is still needed in the design and introduction of specific protocols for informing patients about the correct multidisciplinary approach to AD and the safety profiles of the available treatments. As mentioned above, such protocols would probably be very useful for improving adherence to medical recommendations and disease control in AD.

FundingFunding for this study was provided by Astellas Pharma S.A.

Conflicts of InterestDr. A. M. Mora is employed by Astellas Pharma España.

The other authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Ortiz de Frutos FJ, Torrelo A, de Lucas R, González MA, Alomar A, Vera Á, et al. Dermatitis atópica desde la perspectiva del paciente: desencadenantes, cumplimiento de las recomendaciones médicas y control de la enfermedad. Estudio DATOP. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2014;105:487–496.