Linear IgA bullous dermatosis is an acquired subepidermal immunoglobulin-mediated vesiculobullous disease. In this retrospective, observational, descriptive study, we describe the clinical characteristics, treatments, and outcomes of 17 patients with linear IgA bullous dermatosis. Two children had been vaccinated 2 weeks before the onset of symptoms, 2 had had bronco-obstructive respiratory symptoms, and 1 had received intravenous antibiotic therapy. We also observed an association with autoimmune hepatitis in one patient and alopecia areata in another. One boy had VACTERL association. Diagnosis was confirmed by histopathology and direct immunofluorescence. Sixteen patients were treated with dapsone, which was combined with oral corticosteroids in 8 cases and topical corticosteroids in two. Of note in this series was the occurrence of relapses in the perioral area coinciding with infections and vaccination, and the association between linear IgA bullous dermatosis and autoimmune hepatitis and VACTERL association.

La dermatosis ampollar IgA lineal es una enfermedad vesicoampollar subepidérmica, adquirida, mediada por inmunoglobulinas. Presentamos nuestra serie con el objetivo de describir las características clínicas, evolución y tratamientos instaurados.

Se realizó un estudio descriptivo, observacional retrospectivo. Se incluyeron 17 pacientes. Como antecedentes 2 niños recibieron vacunas 2 semanas antes del inicio de los síntomas; en 2 casos la enfermedad estuvo precedida por cuadros respiratorios broncoobstructivos. Un paciente recibió antibioticoterapia endovenosa antes del inicio del cuadro. Hallamos asociación con hepatitis autoinmune en un caso y con alopecia areata en otro. Un niño padecía asociación VACTERL. El diagnóstico se confirmó con histopatología e inmunofluorescencia directa. Como tratamiento 16 pacientes recibieron dapsona, 8 de ellos asociaron corticoides orales y 2 esteroides tópicos.

Destacamos la presencia de rebrotes con compromiso perioral ante cuadros infecciosos e inmunizaciones, la asociación con síndrome de VACTERL y con hepatitis autoinmune.

Linear IgA bullous dermatosis (LABD) is an acquired subepidermal immunoglobulin-mediated vesiculobullous disease that affects both children and adults.1 Children present typical clinical manifestations of LABP, but in adults the disease can mimic herpetiform dermatitis or bullous pemphigoid.2 Diagnosis is based on clinical, histologic, and immunofluorescence findings. The treatment of choice is dapsone.

We present a series of 17 cases of LABD in children and describe the clinical features, treatments, and outcomes.

Material and MethodsThis was a retrospective, observational, descriptive study of all patients with LABD treated at Hospital Ramos Mejía and Hospital Alemán in Argentina and Hospital Sant Joan de Déu in Spain between May 1, 2003 and July 31, 2017. The data were obtained from a review of the children's medical records and the hospitals’ photographic archives.

ResultsSeventeen patients (7 girls and 10 boys) were included in the study (Table 1). Age at diagnosis ranged from 7 months to 7 years (mean, 3.1 years). Two children had been vaccinated against varicella and flu 2 weeks before developing the disease and in another cases, onset had been preceded by broncho-obstructive respiratory disease. Another patient had been treated with intravenous antibiotics immediately before the onset of symptoms. We also observed an association with autoimmune hepatitis in one patient and with alopecia areata in another. Finally, there was 1 case of VACTERL association, which is an association of congenital malformations characterized by the presence of at least 3 of the following: vertebral defects, anal atresia, cardiac defects, tracheoesophageal fistula, renal anomalies, and limb abnormalities.

Characteristics of 17 Children With Linear IgA Bullous Dermatosis.

| Patient | Sex | Age of Onset | Past History | Location | Diagnosis | Initial Treatment | Subsequent Treatment | Disease Course | Duration of Disease |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | 3 y | None | Face, trunk, upper and lower limbs | Compatible biopsy and DIF findingsa | Dapsone 3mg/kg, antihistamines | Dapsone 4-5mg/kg, antihistamines, topical corticosteroids | Multiple flares with perioral involvement preceded by minor viral infections | 3 y; still under treatment |

| 2 | F | 7 y | Autoimmune hepatitis | Face, neck, upper and lower limbs, perianal region | Compatible biopsy and DIF findingsa | Methylprednisone 0.5mg/kg | Dapsone 2mg/kg | Multiple flares with perioral involvement | 1.5 y; complete resolution |

| 3 | F | 2 y | Vaccines (quintuple, varicella, flu) 2 wk before disease onset | Face, trunk, hands | Compatible biopsy and DIF findings | Methylprednisone 0.5mg/kg | Dapsone 1-2mg/kg | Multiple flares | 6 mo; still under treatment |

| 4 | M | 5 y | None | Face, trunk, upper and lower limbs | Compatible biopsy and DIF findingsa | Methylprednisone 0.5mg/kg | Dapsone 1-1.5mg/kg | Multiple flares with perioral involvement, one associated with acute otitis media | 18 mo; still under treatment |

| 5 | M | 4 y | None | Face, upper and lower limbs | Compatible biopsy and DIF findings | Dapsone 1mg/kg | Dapsone 1mg/kg | Complete remission | 3 y; complete resolution |

| 6 | F | 7 mo | VACTERL association and hospitalization due to bronchiolitis 2 wk before disease onset | Face, upper and lower limbs | Compatible biopsy and DIF findingsa | Methylprednisone 1mg/kg | Methylprednisolone 2mg/kg | Complete remission | 6 mo; complete resolution |

| 7 | M | 5 y | Alopecia areata | Face, trunk, upper and lower limbs, perianal region | Compatible biopsy and DIF findings | Dapsone | Dapsone 1mg/kg | Multiple flares | 5 mo; still under treatment |

| 8 | F | 2 y | Intravenous antibiotic therapy immediately before disease onset | Neck, trunk, buttocks | Compatible biopsy and DIF findingsa | Dapsone 0.5mg/kg/d | Dapsone 0.5mg/kg | Multiple flares | 8 mo; complete resolution |

| 9 | M | 4 y | None | Face, trunk, upper and lower limbs | Compatible biopsy and DIF findings | Methylprednisone 1mg/kg | Dapsone 1-3mg/kg | Multiple flares; 1 with perioral involvement preceded by flu vaccination | 1 y; still under treatment |

| 10 | F | 1 y | Vaccination (varicella and flu) 2 wk before disease onset | Face, trunk, upper and lower limbs, vulva | Compatible biopsy and DIF findingsa | Dapsone 0.5mg/kg/d | Dapsone 3mg/kg with temporary addition of methylprednisone 1mg/kg due to poor response | Multiple flares | 1 y; still under treatment |

| 11 | F | 2 y | None | Face, upper and lower limbs | Compatible biopsy and DIF findings | Methylprednisone 1mg/kg | Dapsone 1mg/kg | Single flare | 4 mo; still under treatment |

| 12 | M | 4 y | None | Face and scalp | Compatible biopsy and DIF findingsa | Dapsone | Dapsone | Complete remission | Complete resolution |

| 13 | M | 4 y | None | Face, trunk, upper and lower limbs, perianal region, oral mucosa | Compatible biopsy and DIF findingsa | Methylprednisone 1mg/kg | Dapsone 0.5-1mg/kg | Multiple flares | 2 y; complete resolution |

| 14 | M | 3 y | None | Face, scalp, upper and lower limbs, perianal region | Compatible biopsy and DIF; positive IIF: IgA antibodies in dermo-epidermal basement membrane zone | Dapsone 2.5mg/kg | Dapsone 1-4mg/kg, topical corticosteroids, antihistamines | Multiple flares | 3 y before loss to follow-up |

| 15 | M | 2 y | None | Face and perianal region | Compatible biopsy and DIF findingsa | Dapsone | Dapsone | Single flare | 1 y; complete resolution |

| 16 | M | 2 y | Cold with fever immediately before disease onset | Face, scalp, upper and lower limbs, perianal region | Compatible biopsy and DIF findingsa | Methylprednisone 0.5mg/kg | Dapsone 0.5-1.5mg/kg, topical corticosteroids | Multiple flares with perioral involvement preceded by minor viral infections | 2 y; still under treatment |

| 17 | M | 1 y | None | Face, outer ears, trunk, upper and lower limbs, perianal region, oral and anal mucous membranes | Compatible biopsy and DIF findingsa | Methylprednisone 1mg/kg | Dapsone 0.5-1.5mg/kg | Multiple flares with perioral involvement preceded by minor viral infections | 2 y; still under treatment |

Abbreviations: DIF, direct immunofluorescence; F, female; IIF, indirect immunofluorescence; M, male.

All 17 patients had the classic features of LABD. Two patients (cases 13 and 17, Table 1) had oral mucosal involvement and 1 of these also had anal mucosal lesions.

Diagnosis was confirmed by histopathology and direct immunofluorescence (DIF) in all cases.

Screening for glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency was performed before administration of dapsone in all patients. While we were awaiting the results of this test, 8 patients were started on systemic corticosteroids to accelerate clinical improvement. On confirmation of normal G6PD activity, the corticosteroids were withdrawn and treatment started with dapsone. Sixteen patients received dapsone at a dosage of between 0.5 and 5.5mg/kg/d; 8 patients were additionally treated with oral corticosteroids and 2 with topical corticosteroids. The remaining patient, the boy with VACTERL association, was treated with systemic corticosteroids only.

Six of the 17 children experienced flares with perioral involvement: 5 following a minor infection and 1 following a flu jab. The 2 patients who had been vaccinated prior to onset of LABD (cases 3 and 10, Table 1) experienced multiple flares and continued under treatment for 6 and 12 months respectively. There were no clinically significant differences between the 2 patients with mucosal involvement (cases 13 and 17, Table 1) and the rest of the group.

The lesions resolved completely in 7 patients within 6 months to 3 years. Nine patients are still receiving treatment and 1 was lost to follow-up after 3 years.

DiscussionLABD, also known as chronic bullous dermatosis of childhood, is a rare disease, with an incidence of just 0.5 to 2.3 cases per million inhabitants per year.3 Nevertheless, it is still the most common blistering disease in children.4

The etiology of LABD is unknown, although a strong association has been described for a number of haplotypes, such as HLA Cw7, B8, and DR3, which are known to confer susceptibility for early disease onset. Detection of tumor necrosis factor 2, on the other hand, is associated with worse prognosis in the form of longer disease duration.3

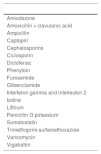

One characteristic feature of LABD is that its onset is frequently preceded by one of several triggering factors, including drugs. The most common triggering drug in adults is vancomycin. In children, onset of LABD has been linked to β-lactams, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and anticonvulsants, among others5,6 (Table 2). Less common associations include vaccines, infections, autoimmune disorders (ulcerative colitis and systemic lupus erythematosus) and cancer (non-Hodgkin lymphoma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, and bladder cancer).3 In our series, 2 patients (11.7%) had been vaccinated against flu and varicella 2 weeks before the onset of LABD, and another (with an existing diagnosis) experienced a flare in symptoms after receiving a flu jab. There were 2 potential autoimmune triggers: alopecia areata and autoimmune hepatitis.

Drugs Associated with Linear IgA Bullous Dermatosis.

| Amiodarone |

| Amoxicillin + clavulanic acid |

| Ampicillin |

| Captopril |

| Cephalosporins |

| Ciclosporin |

| Diclofenac |

| Phenytoin |

| Furosemide |

| Glibenclamide |

| Interferon gamma and interleukin 2 |

| Iodine |

| Lithium |

| Penicillin G potassium |

| Somatostatin |

| Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole |

| Vancomycin |

| Vigabatrin |

The link with VACTERL association has been previously described,7 and considering the complex nature of this syndrome, it is possible that LABD in such cases is induced by a drug or an infection. In our case, the boy had been hospitalized for bronchiolitis, treated with oxygen and antipyretics, a week before the onset of symptoms.

The pathophysiologic mechanism responsible for triggering the autoimmune response in LABD remains unknown. The main antigen target is the 180-kDa bullous pemphigoid antigen 2 (BP180), which is a transmembrane protein with a key role in dermal-epidermal adhesion.2 This protein has an intracellular, a transmembrane, and an extracellular component. The extracellular component spans the lamina lucida and interacts with the laminin-5 molecules that form the anchoring fibrils of the lamina densa via its carboxyl terminus. This terminus can undergo hydrolysis to form a soluble fragment, LAD-1. Most patients have antibodies that react against LAD-1 and against a 97-kDa antigen within this fragment.8 There have also been reports, albeit fewer, of immunoglobulins directed against other basement membrane antigens, such as laminin-332, laminin-γ1, and collagen vii.9

There are 2 main clinical variants of LABD: one that affects children and another that affects adults. The first variant, known as chronic bullous dermatosis of childhood, generally affects children younger than 5 years. Adults can develop LABD at any time, but onset is more common after 60 years of age. The 2 variants have certain clinical differences, but their histologic and DIF findings are identical.10

The characteristic cutaneous manifestations of LABD are tense vesicles and blisters on a normal or erythematous base. The lesions form a rosette-like pattern with a crust in the center; new blisters can form around the edge, leading to what is known the string of pearls sign (Fig. 1). Lesions are mainly located on the trunk, the lower abdomen, the axillae, the thighs, and around the mouth.10 Lesions on the palms and soles are less common. In adults, lesions are most notably located on the extensor surfaces of limbs, the trunk, the buttocks, and the face. The string of pearls sign is uncommon in this case.2 Symptoms can vary from mild pruritus to intense pain. Lesions resolve without scarring, but they can leave color changes.1

Involvement of the oral and conjunctival mucosa is common and can occur at any age, although it is more common in adults.11,12

Diagnosis is based on clinical, histologic, and immunofluorescence findings.

The clinical characteristics have been described above.

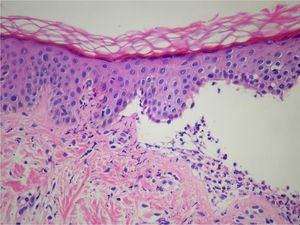

Histology shows subepidermal blisters with a predominantly neutrophilic inflammatory infiltrate in the dermis1 (Fig. 2).

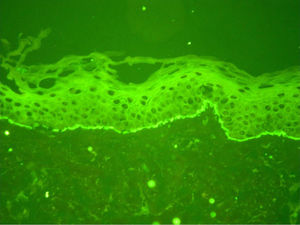

As LABD has many overlapping features with other blistering diseases, immunofluorescence studies are recommended to check for the presence of immunoglobulins.13

DIF is positive in 100% of cases and the findings manifest as linear IgA deposits in the basement membrane zone of normal and perilesional skin9 (Fig. 3). IgM and C3 deposits may be observed in some cases.10 Although the name linear IgA bullous dermatosis clearly comes from the linear IgA deposits observed in the basement membrane zone, it is still unclear whether a diagnosis can be established based on this finding alone. In fact, similar deposits have been reported in several cases of subepidermal blistering diseases other than LABD, such as bullous pemphigoid, mucous membrane pemphigoid, gestational pemphigoid, and bullous epidermolysis.14

Indirect immunofluorescence is also used to detect circulating autoantibodies against different antigens and its sensitivity ranges between 30% and 50%. The test's sensitivity increases to close to 70% when a salt-split skin substrate is used (incubation of skin in 1mol/L salt to separate the epidermis from the dermis). As previously mentioned, most patients have antibodies against 97-kDa and 120-kDa antigens. The detection of one type or another depends on whether cell cultures (97 kDa) or skin extracts (120 kDa) are used for the diagnostic tests.13

The differential diagnosis of LABD should include hereditary epidermolysis bullosa, which tends to manifest at birth in the form of blistering lesions in friction areas or as herpetiforme dermatitis. This latter condition can be distinguished from LABD as it is more commonly associated with gluten-sensitive enteropathy, does not affect the mucosa, and shows granular IgA deposits in DIF. The other entity that should be included in the differential diagnosis is bullous pemphigoid, which has overlapping clinical features with LABD, but differs in that it has IgG and C3 deposits in the basement membrane zone.1 As established in the International Consensus Statement on Mucous Membrane Pemphigoid, patients with typical clinical features of this disease together with linear IgA deposits in the basement membrane zone on DIF should be considered carriers of linear IgA mucous membrane pemphigoid.

The treatment of choice for LABD is dapsone at a dosage of between 0.5 and 3mg/kg/d. It is effective as monotherapy or combined with corticosteroids, antibiotics, or colchicin.15 Screening for G6PD deficiency should be performed prior to treatment initiation, as patients with this disorder may have hemolytic anemia.3 Follow-up tests should include a complete blood count and reticulocyte count to check for agranulocytosis or hemolysis. If the disease does not resolve with standard doses of dapsone, then systemic corticosteroids, mycophenolate mofetil, ciclosporin A, or oral antibiotics, such as erythromycin and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, can be added.8,16 Careful consideration should be given to the potential adverse effects of additional treatments, as LABD is a benign disease that generally presents with flares before resolving spontaneously. We therefore recommend weighing up the potential harms and benefits of all drugs. Patients who do not tolerate dapsone can be treated with sulfapyridine or colchicin.15 The drug should be gradually tapered and withdrawn once the disease has been brought under control and the patient has been free of lesions for some time.

Most cases resolve within 3 to 6 years, although there have been reports of cases persisting beyond puberty.

ConclusionsAlthough LABD is one of the most common acquired blistering diseases in children, it is still rare. The clinical, histopathologic, and DIF findings in our series of 17 patients coincide with those described in the literature. Our findings suggest that vaccination should be considered as a possible trigger for LABD in children. Other noteworthy observations are the presence of flares with perioral involvement in patients following an infection or vaccine and the associations with VACTERL syndrome (the second such case to be published) and with autoimmune hepatitis (to our knowledge, the first such case).

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Díaz MS, Morita L, Ferrari B, Sartori S, Greco MF, Sobrevias Bonells L, et al. Dermatosis ampollar IgA lineal: serie de 17 casos. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2019;110:673–680.