Foot eczema is a common complaint encountered by skin allergists.

ObjectivesTo study a series of patients with foot eczema who underwent patch testing and describe their demographic profile, diagnoses, and the main allergens involved.

Material and methodsCross-sectional observational study of all patients tested with the standard Spanish patch test series at a dermatology department over a period of 13 years (2004–2016). We studied patch test results and definitive diagnoses by comparing different subgroups of patients with foot eczema.

ResultsOf the 3265 patients included in the study, 308 (9.4%) had foot eczema, 176 (57.9%) had foot eczema only and 132 (42.1%) had concomitant foot and hand eczema. Positive patch test results were more common in patients with foot eczema only (positivity rate of 61.5% vs 53.4% for foot and hand eczema). In the subgroup of patients with concomitant foot and hand involvement, patients aged under 18 years had a lower rate of positive results (51.3% vs 64.6% for patients >18 years). Potassium dichromate was the most common allergen with current relevance in all subgroups. The main diagnosis in patients with foot involvement only was allergic contact dermatitis (49.1%). In the subgroup of patients with concomitant hand and foot eczema, the main diagnoses were psoriasis in adults (33.6%) and atopic dermatitis in patients aged under 18 years (60.0%).

ConclusionPatch tests are a very useful diagnostic tool for patients with foot eczema with or without concomitant hand involvement.

La dermatitis de pies es un motivo frecuente de consulta en las Unidades de Alergia Cutánea.

ObjetivosConocer las características demográficas, el diagnóstico y los alérgenos más frecuentemente implicados en los pacientes que han sido sometidos a las pruebas epicutáneas.

Material y métodosEstudio observacional transversal en un Servicio de Dermatología con todos los pacientes estudiados con la batería estándar española durante 13 años (2004–2016). Comparamos los resultados de las pruebas epicutáneas y los diagnósticos finales entre los distintos subgrupos de pacientes con eczema de pies.

ResultadosEstudiamos un total de 3265 pacientes, 308 (9,4%) presentaban eczema en los pies, 176 (57,9%) tenían afectación solo en los pies y 132 (42,1%) afectación concomitante en manos y pies. En el subgrupo con afectación exclusiva en los pies se observó un mayor porcentaje de pacientes con pruebas epicutáneas positivas (61,5% solo pies, 53,4% manos y pies). En el subgrupo de afectación concomitante de manos y pies se observó un menor porcentaje de pruebas epicutáneas positivas entre los menores de 18 años (51,3% en menores y 64,4%mayores). El alérgeno con relevancia presente más frecuente en todos los subgrupos fue el dicromato potásico. La dermatitis de contacto alérgica (49,1%) fue el diagnóstico más frecuente en los pacientes con afectación exclusiva de los pies, mientras en los pacientes con eczema en manos y pies fue, la psoriasis (33,6%) en adultos, y la dermatitis atópica en los menores de 18 años (60,0%).

ConclusiónLa realización de pruebas epicutáneas es de gran utilidad tanto en los pacientes con eczema de afectación exclusiva de los pies como en aquellos con afectación concomitante de manos y pies.

Foot eczema is a common presenting complaint. The prevalence of allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) involving the feet varies considerably and is thought to affect between 1.5% and 24.2% of all patients undergoing patch testing.1,2 Concomitant involvement of both the hands and the feet is not uncommon. According to the literature, the prevalence of the condition when it affects both sites is 5.4% in the general population.3,4

Clinical diagnosis of foot eczema is relatively easy. However, classification is complex, since there are many morphological variations and it is difficult to distinguish between contact eczema (irritant or allergic) and atopic eczema, which can occur alone or in combination.1,2 Very often, it is difficult to differentiate between eczema and psoriasis. Therefore, in chronic disease, it is almost mandatory to perform patch tests to detect allergens that act as a cause or complication of foot eczema.5,6 The allergens most frequently involved in foot eczema are found in the material used for footwear and include potassium dichromate, p-tert butylphenol-formaldehyde resin, and mercaptobenzothiazole.7

Prevalence and patch test results have been widely analyzed in epidemiological studies in patients with hand eczema,3,4 although almost no studies provide data on foot eczema.8 Therefore, we performed a study to ascertain the demographic profile, final diagnosis, and allergens involved in patients with suspected foot eczema who come to our clinic for patch testing.

ObjectivesThe main objectives of the study were as follows:

- –

To determine the demographic characteristics of patients with foot eczema assessed by means of patch testing and to establish which allergens are most commonly involved in foot eczema.

The secondary objectives were as follows:

- –

To determine whether there are differences between the final diagnosis and the results of patch testing between the sexes and age groups.

- –

To compare epidemiological data, final diagnosis, and patch test results from patients referred for suspected eczema on the feet only with those from patients with suspected eczema on the hands and feet.

Ours was an observational, cross-sectional study performed between January 2004 and December 2016. We included all patients who had undergone patch testing with the standard series of the Spanish Contact Dermatitis and Skin Allergy Research Group (GEIDAC) at the skin allergy clinic of the dermatology department of a tertiary hospital. Patient information was obtained from the anonymized database used in clinical care. We recorded patient data, the allergen series applied, the results, and their relevance. The clinical data recorded for each patient were age, sex, location of the lesions (feet only, both hands and feet, and other sites, including patients with diffuse or generalized involvement who also had lesions on their feet), cause of eczema, and final diagnosis. The possible diagnoses were as follows:

- 1

ACD.

- 2

Irritant contact dermatitis (ICD).

- 3

Atopic eczema (including dyshidrosis). Patients with dyshidrotic eczema were included in this section.

- 4

Psoriasis.

- 5

Other.

Based on the location of lesions, we established 2 study groups:

- –

Total study group, other locations of eczema (including any site on the body where the lesion appeared).

- –

Group with suspected foot eczema, which was in turn divided into:

- •

Patients with suspected eczema on both the hands and the feet.

- •

Patients with suspected eczema on the feet only. (Patients who in addition to presenting with foot eczema had involvement at sites other than the hands were not included in this group).

The groups were compared by sex (male/female) and age (<18 years/≥18 years).

Patch testing methodsThe allergens used in the standard GEIDAC series were supplied by Chemotechnique Diagnostics AB. The patches were prepared with adhesive Finn-Chamber strips (Epitest, Oy), attached with Scanpor adhesive tape (Norgeplaster A/S Kristiandsand), and removed at 48 hours. Readings were taken at 48 and 96 hours based on the evaluation criteria recommended by the International Contact Dermatitis Research Group. A late reading (7 days) was taken in doubtful cases.

Statistical analysisData were processed using SPSS 20 (IBM Corp). Qualitative variables were analyzed using contingency tables and the χ2 test. Statistical significance was set at ≤ .05. Age as a continuous variable (quantitative) was compared with qualitative variables (nominal) using nonparametric tests, namely, the Mann-Whitney or Kruskal-Wallis test, depending on the number of values for the qualitative variables.

ResultsBetween January 2004 and December 2016, we performed patch testing with the standard GEIDAC series on 3265 patients, of whom 308 (9.4%) had foot eczema. Of these 308 patients, 176 (57.9%) had foot eczema only, whereas 132 (42.1%) had concomitant hand and foot eczema.

Demographic DataTable 1 shows the distribution by sex and age of each of the subgroups. Of note, the sexes were well balanced, especially in the group with concomitant hand and foot involvement, and a higher number of patients who underwent patch testing in the foot eczema group were aged <18 years.

Demographic Data of the Study Population.

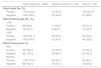

Table 2 shows the percentage of positive results for each subgroup. It is noteworthy that this is greater in the subgroup with foot eczema only, especially in patients aged ≥18 years.

Results of Patch Testing.

| Total Sample (N = 3265) | Hands and Feet (n = 132) | Feet (n = 176) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patch tests, No. (%) | |||

| Positive | 1735 (53.8) | 70 (53.4) | 109 (61.5)a |

| Negative | 1530 (46.2) | 62 (46.6) | 67 (38.5) |

| Patch tests by age, No. (%) | |||

| <18y | |||

| Positive | 98 (38.9) | 1 (10.0)a | 20 (51.3) |

| Negative | 154 (61.1) | 9 (90.0) | 19 (48.7) |

| ≥18y | |||

| Positive | 1637 (55.1) | 69 (57.0) | 89 (64.4) |

| Negative | 1376 (44.9) | 53 (43.0) | 48 (35.6) |

| Patch tests by sex (%) | |||

| Men | |||

| Positive | 557 (46.7) | 24 (39.3) | 41 (54.7) |

| Negative | 661 (53.3) | 38 (60.7) | 33 (45.3) |

| Women | |||

| Positive | 1178 (57.6) | 46 (65.7) | 69 (66.7) |

| Negative | 869 (42.4) | 24 (34.3) | 33 (33.3) |

In patients with concomitant hand and foot eczema, 90% of the patch tests were negative in patients aged <18 years. No significant differences were found for the allergens or for the foot eczema group.

Table 3 shows positive results with present relevance for allergens from the standard series. Potassium dichromate was the most common allergen with present relevance in all of the subgroups. Of note, the most common allergens in the case of foot eczema only were footwear components, namely, chromium, rubber accelerators, and glues.

Most Common Allergens With Present Relevance.

| Total Sample | Hands and Feet | Feet | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Most common allergens, No. (%) | • Potassium dichromate | 126 (15.6) | • Potassium dichromate | 19 (48.7) | • Potassium dichromatea | 49 (70)a |

| • Nickel sulfate | 102 (12.6) | • MCI/MI | 5 (12.8) | • Mercapto mix | 3 (4.3) | |

| • MCI/MI | 101 (12.5) | • Nickel sulfate | 4 (10.3) | • 4-tert-butylphenol formaldehyde resin | 2 (2.9) | |

| • Balsam of Peru | 70 (8.7) | • 4-phenylenediamine base | 1 (2.6) | • Fragrance mix I | 2 (2.9) | |

| • 4-phenylenediamine base | 49 (6.1) | • Own products | 2 (2.9) | |||

| Most common allergens in patients aged <18 y, No. (%) | • Potassium dichromate | 12 (21.1) | • Potassium dichromate 0.5% | 1 (100.0)a | • Potassium dichromate 0.5% | 11 (68.8)a |

| • Nickel sulfate | 4 (7.0) | • MCI/MI | 0 (0) | • Mercapto mix 2% | 3 (18.8)a | |

| • MCI/MI | 7 (12.3) | • Nickel sulfate 5% | 0 (0) | • 4-tert-butylphenol formaldehyde resin 1% | 1 (6.2) | |

| • Balsam of Peru | 6 (10.5) | • Balsam of Peru 25% | 0 (0) | • Balsam of Peru 25% | 1 (6.2) | |

| • 4-phenylenediamine base | 7 (12.3) | |||||

| Most common allergens in patients aged ≥18 y, No. (%) | • Nickel sulfate | 18 (46.2)a | • Potassium dichromate | 18 (46.2) | • Potassium dichromate | 38 (70.4)a |

| • Potassium dichromate | 5 (12,8) | • MCI/MI | 5 (12.8) | • 4-tert-butylphenol formaldehyde resin | 1 (1.9) | |

| • MCI/MI | 4 (10.3) | • Nickel sulfate | 4 (10.3) | • Fragrance mix I | 2 (3.7) | |

| • Balsam of Peru | 2 (5.1) | • Balsam of Peru | 2 (5.1) | • Own products | 2 (3.7) | |

| • 4-phenylenediamine base | 1 (2.6) | • Thiuram mix | 1 (2.6) | |||

| Most common allergens by sex, No. (%) | ||||||

| Males | • Nickel sulfate | 19 (6.1) | • Potassium dichromate | 10 (47.6)a | • Potassium dichromate | 21 (72.4)a |

| • Potassium dichromate | 65 (20.8) | • MCI/MI | 2 (9,5) | • Mercapto mix | 1 (3.4) | |

| • MCI/MI | 36 (11.5) | • 4-phenylenediamine base | 1 (4.8) | • 4-tert-butylphenol formaldehyde resin | 1 (3.4) | |

| • Balsam of Peru | 42 (13.5) | • Thiuram mix | 1 (4,8) | • Thiuram mix | 1 (3.4) | |

| • Fragrance mix I | 18 (5.8) | • Balsam of Peru | 2 (9.5) | • Balsam of Peru 25% | 1 (3.4) | |

| Females | • Nickel sulfate | 83 (16.8)a | • Potassium dichromate | 9 (47.4)a | • Potassium dichromate | 28 (68.3)a |

| • Potassium dichromate | 61 (12.3) | • MCI/MI | 3 (15,8) | • Mercapto mix | 2 (4.9) | |

| • MCI/MI | 65 (13.1) | • Nickel sulfate | 4 (21.1) | • Fragrance mix I | 2 (4.9) | |

| • Balsam of Peru | 28 (5.7) | • Formaldehyde | 1 (5.3) | • Own products | 1 (2.4) | |

| • 4-phenylenediamine base | 38 (7.7) | • Colophony | 1 (1.4) | |||

Abbreviation: MCI/MI, methylchloroisothiazolinone/methylisothiazolinone.

Table 4 shows that psoriasis was the most common diagnosis in patients with concomitant foot and hand eczema, whereas ACD was a more common diagnosis in patients with foot eczema. The frequency of atopic dermatitis in patients aged <18 years was noteworthy, especially in the group with concomitant hand and foot eczema.

Final Diagnosis.

| Total Sample | Hands and Feet | Feet | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Most common final diagnosis, No. (%) | • ACD 1054 (33.2) | • PS 43 (33.6)a | • ACD 84 (49.1)a |

| • ICD 821 (25.1) | • ACD 40 (31.1) | • ICD 35 (20.5) | |

| • AD 418 (13.2) | • AD 21 (16.4) | • AD 24 (14.0) | |

| • PS 221 (7.0) | • ICD 19 (14.8) | • PS 10 (5.8) | |

| • Other 751 (21.5)b | • Other 9 (4.1)b | • Other 23 (10.6)b | |

| Most common final diagnosis in patients aged <18 y, No. (%) | • AD 92 (36.7)a | • AD 6 (60.0)a | • ACD 18 (47.4) |

| • ACD 70 (29.9) | • ICD 2 (20.0) | • AD 13 (34.2) | |

| • ICD 41 (16.3) | • ACD 1 (10.0) | • ICD 7 (18.4) | |

| • PS 6 (2.4) | • PS 1 (10) | • PS 0 (0) | |

| • Other (14.7) | |||

| Most common final diagnosis in patients aged ≥18 y, No. (%) | • ACD 984 (33.4) | • PS 42 (35.6)a | • ACD 66 (49.6) |

| • ICD 780 (26.5) | • ACD 39 (33.1) | • ICD 28 (21.1) | |

| • AD 326 (11.1) | • ICD 17 (14.4) | • AD 11 (8.3) | |

| • PS 212 (7.2) | • AD 15 (12.7) | • PS 10 (7.5) | |

| • Other (21.8)b | • Other 9 (4.2)b | • Other 25 (13.5)b | |

| Most common diagnoses by sex, No. (%) | |||

| Males | • ACD 364 (30.8) | • PS 22 (36.1)a | • ACD 35 (47.3) |

| • ICD 281 (23.8) | • ACD 18 (29.5) | • AD 16 (21.6) | |

| • AD 180 (15.2) | • AD 10 (16.4) | • ICD 14 (18.9) | |

| • PS 111 (9.4) | • ICD 9 (14.8) | • PS 2 (2.7) | |

| • Other (20.8)b | • Other 3 (3.2)b | • Other 8 (9.5)b | |

| Females | • ACD 690 (34.2)a | • ACD 22 (32.8)a | • ACD 49 (50.5) |

| • ICD 540 (26.8) | • PS 21 (31.3) | • ICD 21 (21.6) | |

| • AD 277 (13.7) | • AD 11 (16.4) | • AD 8 (8.2) | |

| • PS 107 (5.3) | • ICD 10 (14.9) | • PS 8 (8.2) | |

| • Other (20)b | • Other 6 (4.6)b | • Other 15 (11.5)b | |

Abbreviations: AD, atopic dermatitis; ACD, allergic contact dermatitis; ICD, irritant contact dermatitis; PS, psoriasis.

Suspected foot eczema is a frequent presenting complaint in our skin allergy unit and is observed in approximately 10% of patients who undergo patch testing. More than 40% of these patients also had hand lesions. This subgroup has unusual epidemiological characteristics, and the results of patch testing and the final diagnosis differ from those of the group with foot eczema only.

In epidemiological terms, the present series highlights a balance between the sexes. Other studies report a greater number of females.6,9,10 Of note, we performed patch testing in a high percentage of children and adolescents with foot eczema. While eczema is common in children, most are clinically diagnosed with atopic dermatitis and very few undergo patch testing despite current recommendations to perform patch testing in patients with treatment-refractory atopic dermatitis or atopic dermatitis with an “atypical” distribution.11–14 In the present series, we believe that the large number of children, especially in those with foot eczema only, is due to the fact that the feet are not considered a “typical” location for atopic dermatitis, with the result that the case is referred in order to rule out ACD. Furthermore, we agree with Isaksson et al.,15 who recommend patch testing in all children with atopic dermatitis who present with chronic eczema on the hands, feet, or both.

We found patch testing to be very useful in patients with foot eczema, since the results were positive in a higher percentage than in the rest of the population studied, especially in those patients with foot involvement only. Present relevance was also more common in this population. Our data are similar to those of Febriana et al.16 and Priya et al.,8 who reported positive results in 66.7% and 88% of patients, respectively. Therefore, we recommend this approach in cases of chronic foot eczema. As for patients with concomitant hand and foot eczema, the results of patch testing were more often negative in patients aged <18 years. Negative results in patch testing should also be interpreted as being useful. In the subgroup with concomitant hand and foot disease in particular, we should consider the possibility that the patient has psoriasis or atopic dermatitis.

Consistent with results from other studies, we found the most common allergen to be potassium dichromate.17 This allergen is usually associated with footwear18; since it is used to tan leather, it is present in leather shoes. The association between foot eczema and allergy to potassium dichromate was so strong that we believe any positive result with chromium in patch tests should lead us to ask whether the patient has foot eczema, especially in summer. Hansen et al.19 concluded that patients with positive results for chromium (III) constitute a group with multiple allergies to footwear and that in patients with a positive result to chromium (VI), leather was the main suspected source of exposure. The European Union has been a pioneer in setting limitations for hexavalent chromium content in leather goods. The amount of chromium used in leather tanning in Europe is regulated by European standard EN 420 and the EU Ecolabel for footwear. As far back as 1994, the European Union included specifications on hexavalent chromium content in standard EN 420 on protective gloves, limiting the substance to a maximum of 2mg/kg. The EU Ecolabel for footwear specifies that the concentration of chromium (VI) in the finished product must not exceed 10 ppm.20 Nevertheless, we think that vegetable tanning, which scarcely uses chromium, should be incentivized in the manufacture of footwear. The majority of studies report that nickel sulfate is the most frequent allergen.21–25 In Indonesia, mercapto mix is the most prevalent allergen and is probably associated with the use of rubber slippers by some of the population.16 In a study on ACD of the feet performed in Turkey, Özkaya and Ekinci9 found nitrofurazone to be the most frequent allergen. Consequently, the main cause of ACD of the foot can differ from one country to another.

The most common final diagnosis in our study was ACD, and the most frequent cause was footwear. The high prevalence of ACD of the foot and its association with footwear can be seen in other studies,6,8,26 and the disease is thought to be more frequent in warm, humid climates.16 Foot sweating, together with friction and occlusion by the shoe, makes it easier for people to become sensitized to the materials used in the manufacture of footwear.

However, ACD was not the most frequent diagnosis in some subgroups in the present series. Psoriasis is more frequent in adults with suspected hand and foot eczema. This finding is rarely reported in the literature,27 although this is not surprising, since in clinical practice it is very difficult to distinguish between eczema and psoriasis, and patients often present eczematized psoriasis or the eczema acts as a Koebner phenomenon and triggers psoriasis. The refractoriness of palmoplantar psoriasis to currently available treatments leads the physician to refer the patient for examination in order to rule out overlapping ACD. In children and adolescents, however, the most common final diagnosis was atopic dermatitis. Of note, the feet are a common site for atopic dermatitis in childhood.28 In cases of psoriasis and atopic dermatitis with eczema on the hands and/or feet that do not respond to seemingly appropriate treatment, we believe that patch testing should be proposed in order to rule out overlapping ACD.

ConclusionsThe suspicion of foot eczema is a common reason for visits to the skin allergy unit. Patch testing is very useful. Clinically relevant positive results are obtained in a larger percentage of patients than in the rest of the study population. ACD is the most common final diagnosis in patients with foot eczema only. Potassium dichromate is the most common allergen, and the components of footwear are the main cause.

In the case of patients who also present with hand lesions, the disease is more likely to be psoriasis (in adults) or atopic dermatitis (in children and adolescents). Patch testing is also very useful for ruling out overlapping ACD in this subgroup.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

This study would not have been possible without the patience of Drs. J Bañuls, JF Silvestre, and López del Amo, to whom I am eternally grateful.

Please cite this article as: Sánchez-Sáez JM, López del Amo A, Bañuls J, Silvestre JF. Eczema en los pies en una consulta de alergia cutánea: estudio retrospectivo de 13 años. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2019;110:666–672.