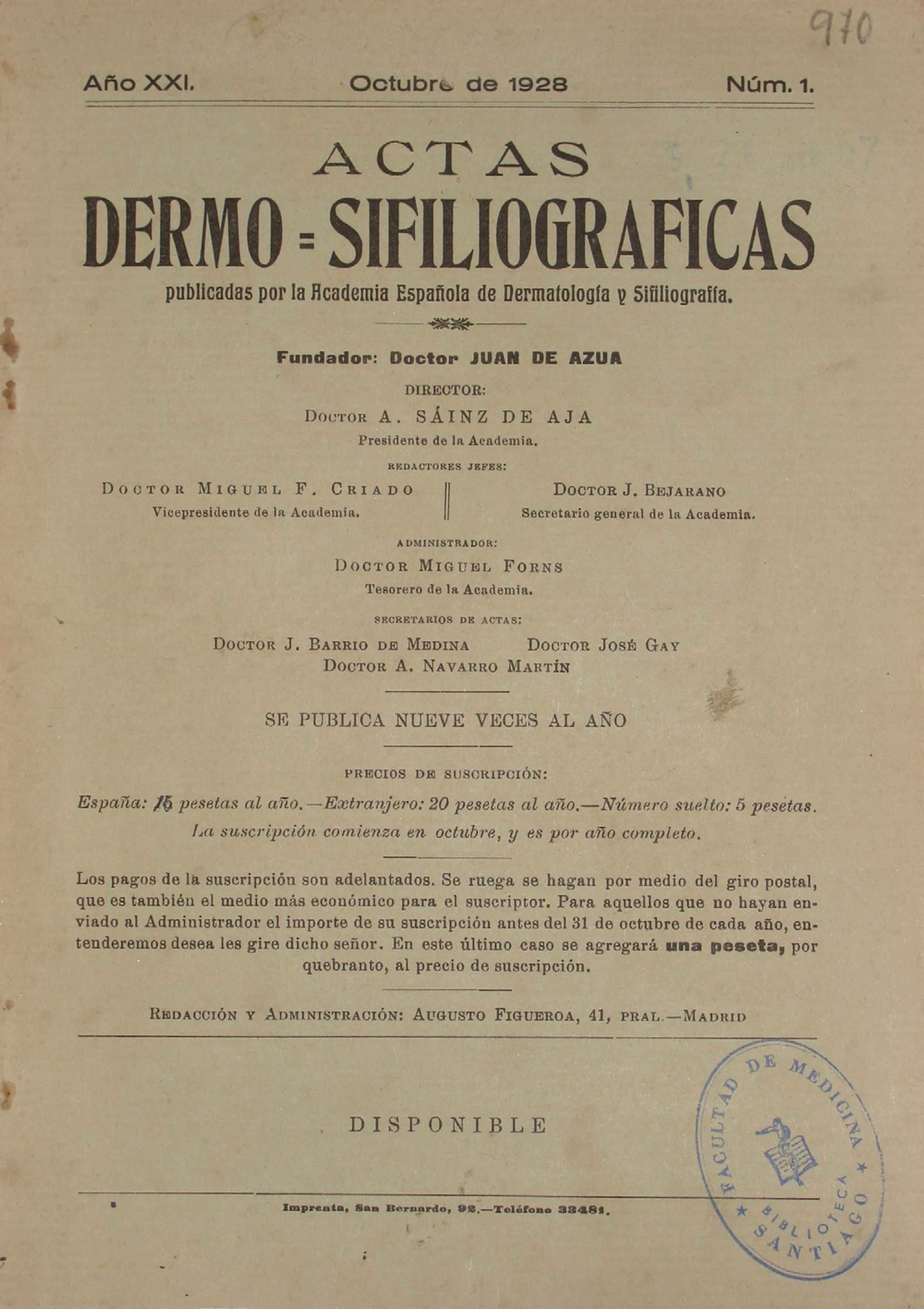

Actas Dermo-Sifiliográficas was born in May 1909. At first, issues appeared in step with the academic year, but publication began to follow the calendar year in 1957. Volume 18 was skipped in 1926-7 in an effort to correct confusion in the numbering of volumes and pages of earlier issues. October 1928 saw the journal grow from 6 issues per year to 9. Although the Spanish Civil War brought publication to a halt during the 1936-7 academic year, Actas Dermo-Sifiliográficas was one of the first Spanish scientific journals to recover from the conflict. The initial print run of 100 copies was increased to 700 after the war. The content evolved over time: while originally conceived to provide a strict account of sessions of the Spanish Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (AEDV) —originally known as the Spanish Academy of Dermatology and Syphilology— the journal gradually came to include review articles, case reports, a section summarizing the content of international journals, news and various other types of writing. The editorial board and the association's board of directors were one and the same for many years. According to the earliest charter, the editor-in-chief was also the president of the association and the associate editor was the association's vice-president. The subjects of articles provide a faithful portrait of how the specialty has changed. Syphilis, a main concern before the introduction of penicillin in the 1940s, was sidelined afterwards. The appearance of 20th-century pharmaceuticals such as salvarsan, sulfa drugs, thiazides, and corticosteroids were soon reflected in the number of articles describing their use. Certain original contributions by Spanish authors to international dermatology first appeared in Actas Dermo-Sifiliográficas. Examples are Azúa's description of pseudoepithelioma and Covisa and Bejarano's of chancriform pyoderma. Volume 50 (1959), which included accounts of the 50th anniversary of the association and the journal, closed with a biography of Enrique Álvarez Sainz de Aja, the only founding member still living at that time.

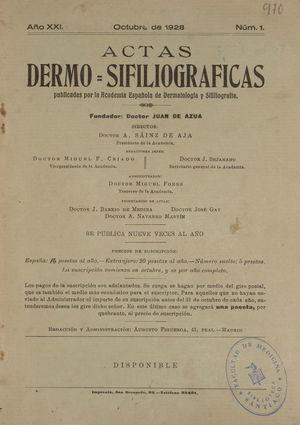

Actas Dermo-Sifiliográficas nació en mayo de 1909. Inicialmente la Revista se publicó por cursos académicos. En 1957 pasó a hacerse por años naturales. El tomo XVIII de la Revista no existe, por un reajuste entre los años de publicación y los tomos realizado en el curso 1926-1927. En octubre de 1928 la Revista aumentó de 6 a 9 ejemplares por año. El curso 1936-1937 no se publicó por el inicio de la Guerra Civil española, pero fue una de las primeras revistas científicas españolas en recuperarse durante la contienda. Su tirada inicial, estimada en unos 100 ejemplares, era ya de 700 poco después de la Guerra Civil. Sus contenidos han ido cambiando progresivamente, pasando de ser el reflejo estricto de las sesiones de la Sociedad Española de Dermatología y Sifiliografía (actual Academia Española de Dermatología y Venereología) a incluir artículos de revisión, casos clínicos, revista de revistas, noticias y diversas secciones. Su comité editorial también ha estado condicionado por la Junta Directiva de esta sociedad al coincidir los cargos durante muchos años. En los primeros reglamentos el director era el presidente de la Academia y el redactor-jefe era el vicepresidente. Los temas tratados son un retrato fiel de la evolución de la propia especialidad. La sífilis pasó de ser predominante, antes de la introducción de la penicilina en los años cuarenta, a ser residual después de esta. Otras grandes aportaciones terapéuticas del siglo xx, como el salvarsán, las sulfamidas, las tiacidas y los corticoides, también tuvieron un eco amplio y rápido en sus páginas. En Actas Dermo-Sifiliográficas se publicaron algunas aportaciones originales de autores españoles a la Dermatología mundial, como los pseudoepiteliomas de Azúa o la piodermitis chancriforme de Covisa y Bejarano. El tomo 50, del año 1959, recoge los actos conmemorativos del primer cincuentenario de la Academia Española de Dermatología y Sifiliografía y de la Revista, que se cierran con una biografía de Enrique Álvarez Sainz de Aja, el único miembro fundador vivo en aquel momento.

Actas Dermo-Sifiliográficas celebrated its centenary in 2009 with a magnificent series of commemorative articles and editorials. However, a task that remained was to assess the importance of the journal throughout its history and to review the content of those first 100 volumes against the backdrop of the social and political history of Spain and the evolution of dermatology as a specialty.

This article—which will be followed by another analyzing the second 50-year period—covers the first 51 years of publication, including 1959. We will discuss the basic format and operation of the journal (number of issues per year, size, editorial board, sections, etc), its content (topics, news, innovations), and we will also look at the changes in the journal's advertising over the decades, another aspect that provides insight into the evolution of our specialty in Spain.

A certain degree of personal bias is inevitable and I do not claim to offer an exhaustive history; however, the sources of information included are documented. If anyone has additional or different information, I would be very happy to receive it. The content has been arranged under a number of headings to facilitate the reading of this material, which at times seems to leave us awash in a sea of details.

Pioneering Dermatology JournalsVery few medical journals can boast a history of over 100 years of active publication. The dermatology journal with the longest history in the select group of publications that have survived for over a century is the Giornale Italiano di Dermatologia e Venereologia founded in 1866: this claim is referred to in an advertisement for the Italian journal published in Actas Dermo-Sifiliográficas in the 1940s (Fig. 1). Another historical dermatology journal is Annales de Dermatologie et de Syphiligrafie, first published on November 20, 1868.1 The British Journal of Dermatology, which began publishing in 1888, is yet another example of a venerable journal in our specialty.2

In Spain, only Anales de la Real Academia Nacional de Medicina, which first appeared in 1879 and is still published 4 times a year,3 has a longer history than Actas Dermo-Sifiliográficas, although they are very different publications. One Spanish journal devoted exclusively to dermatology predated Actas Dermo-Sifiliográficas: Luis Portillo's Revista Española de Dermatología y Sifiliografía, which started publication in 1899 but had disappeared before the constitution of the Second Spanish Republic in 1931.

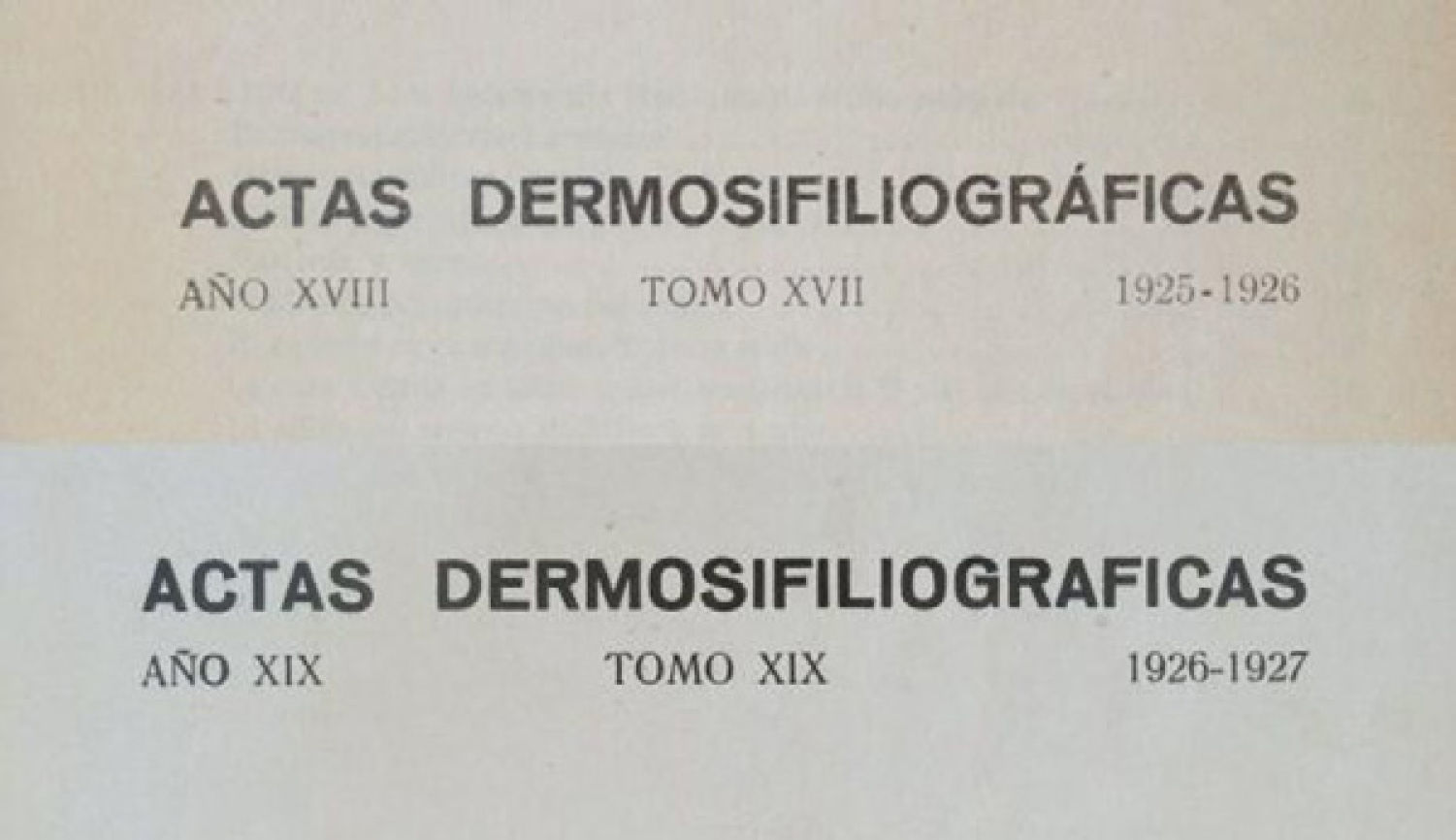

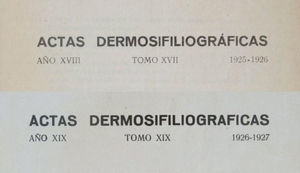

Collections of Actas Dermo-Sifiliográficas and Other Sources ConsultedThe present article is based on material from the 49 volumes of Actas published between 1909 and 1959. If the journal had been published every year from 1909 to 1959 there would have been 51 volumes, but none was published during the 1936-1937 academic year. In addition a volume number was skipped (Fig. 2). The volume that appeared in 1959, which should have been number 51, was published as volume 50.

These headers appeared on issues in the volumes for the 1925-1926 and 1926-1927 academic years. The first indicates that it corresponds to the eighth year of publication but was volume XVII, while the second continues the ordinal numbering for year of publication (the ninth) and the volume number (XIX) now matches it. This change, which was made so that the publication year would coincide with the volume number, meant that volume XVIII of the journal was skipped.

Today, a complete collection of Actas Dermo-Sifiliográficas is a real treasure, and such collections are very rare. There are 3 almost complete collections in Spain's national library: 1 available for consultation and 2 archived collections with restricted access. Some issues are missing from each of these collections, however. The collection owned by the Spanish Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (AEDV) is complete. While it has from time to time suffered from losses through damage and pilfering, we have been able to rebuild the complete collection through the generosity of our members. Prior to the Spanish Civil War, Enrique Álvarez Sainz de Aja replaced, from his personal collection, many issues that had been lost or taken. His gift is noted in the minutes of the meeting of the Academy's board of directors held on September 22, 1933. The widow of Benito Fernández Gómez, another distinguished dermatologist who worked at Hospital de San Juan de Dios, also contributed to the collection after the death of her husband, a gesture formally acknowledged with thanks in an editorial note.4 A few dermatological family dynasties also possess a complete collection. One of these is the Ledo family, one of whose members published in the first issue of Actas.5 The Daudén family also owns a nearly complete collection of Actas Dermo-Sifiliográficas. In writing this article, I have often made use of copies of the journal collected by Manuel Molina García, a physician who began working in the state antivenereal disease unit on January 23, 1939 and was director of the San Lázaro leprosy hospital in Santiago de Compostela. Molina donated his pristine, bound collection comprising every issue published between 1935 and 1981 to the Faculty of Medicine in Santiago de Compostela. These copies include corrections in the donor's own handwriting of the very few typographical errors that appeared in Actas.

Secondary sources in the form of previous studies of the history of the journal are also uncommon and generally quite recent. A preliminary review6 published just before the centenary issue of Actas contained a few errors, some of which have since been corrected.7 A more systematic study by Longo and Daudén—the executive editor and editor-in-chief of the journal, respectively, at the time—was published in the recent book commemorating the centenary of our association.8

A few articles on our history were also published at the time of the 25th, 50th and 75th anniversaries of the journal and the association (the Academy since the 1920s and before that the Spanish Society of Dermatology and Syphilology), although these tended to focus more on the association than its journal. However, in reviewing these articles, I found a comment by Sainz de Aja that tells us that the first meeting of the original association took place on May 6, 1909 in the College of Physicians in Madrid.9 No other source mentions precisely where this meeting took place.10

Commemorative speeches and the treasury reports of the Academy have also contributed interesting information about the journal's growth, especially with regard to details such as the number of subscribers, print runs, costs, and format.

The series of centenary editorials and articles published throughout 2009 were a valuable source of information, particularly concerning the more recent era.7,10–28 Finally, the different versions of the association statutes and bylaws have also been very useful source of information concerning the history of Actas, including precise details of the editorial staff, publication schedule, and operation of the journal.

The Eras of Actas Dermo-SifiliográficasIn one article,6 the history of the journal was divided into 3 phases:

- 1.

Foundation and initial consolidation

- 2.

Post Civil War and continuation

- 3.

Recovery in recent decades

In a more detailed approach, Longo and Daudén8 divided the history of the journal into 6 separate periods as follows: a) founding of the Society and initial consolidation (1909-1922); b) constitution of the Academy and external relations (1922-1936); c) recovery after the Civil War (1937-1966); d) survival (1966-1986); e) reassessment (1986-2006); and f) international projection (2007-present).

Since these 6 periods are well chosen because they accurately reflect the evolution of the journal, I will use them in the present article, although only approximately because of the need to group events into 50-year periods.

The Correct Name of the Journal and Its AbbreviationActas Dermo-Sifiliográficas (dermatology and syphilology proceedings) was founded in 1909 to serve as a record of the proceedings of the meetings of the Spanish Society of Dermatology and Syphilology. As its name makes clear, these are the Actas (defined by the dictionary of the Real Academia Española as a certification or written record) of the meetings of this society.

The second term dermo derives from the dual lexical root denoting the specialty in Greek: derma/dermatós, the first of which was in more general use at the time the journal was founded. This usage is evidenced by the fact that the founder and first editor of Actas, Juan de Azúa, systematically used the term dermitis where we would now use dermatitis. Many of Azúa's disciples, including later authors—such as Javier Tomé Bona, a pioneer among skin disease specialists in Spain—habitually used dermitis until relatively recently. The first volume of Actas contains an example of this usage in a case of dermitis caused by hair dye.29 Some medical centers are also described as dermo-venereológicos, particularly during the first third of the 20th century. Likewise, advertisements for official posts announced vacancies for dermo-venereólogos. The existence of the equivalent prefixes dermo and dermato even led to occasional errors among authors citing the name of the journal; one example is José Gómez Orbaneja who, in his article published to mark the centenary of the birth of José Sánchez Covisa, refers to Actas Dermatosifiliográficas.30

The third term sifilográficas is a clear indication of the prevalence and importance of syphilis at the time the journal was founded. The 2 terms dermo and sifiliográficas are connected with a hyphen and both have initial capital letters in the journal's title.

There is even greater variation and confusion in the use of the abbreviated forms of the journal's name. The abbreviation Actas Dermo-Sif, which appears in the references of many articles published in the early years of Actas citing previously publications in its pages, and the form Actas Derm-Sif, which was used in the 1980s and 1990s, are no longer correct today, and this discrepancy greatly increases the difficulty of bibliographic searches. The abbreviation Actas D.-S. has even been used on occasions.31

The official name of the journal is and has always been Actas Dermo-Sifiliográficas and the official abbreviation in Index Medicus is Actas Dermosifiliogr. This is the form that should be used in any citation.

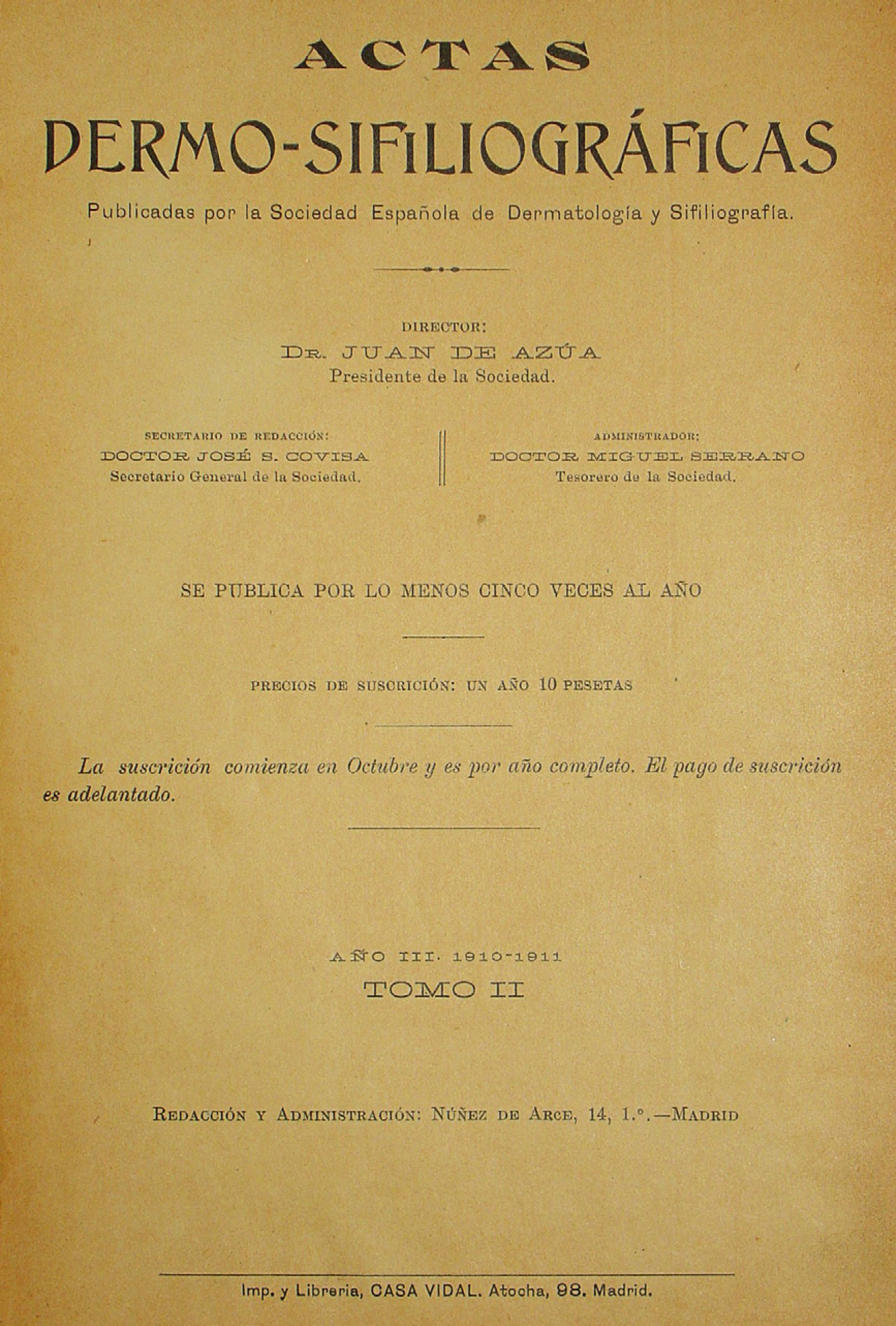

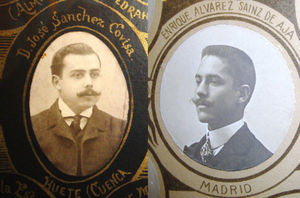

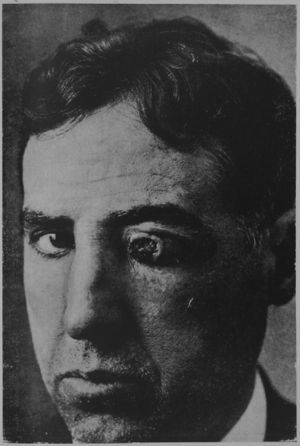

Founding and Initial Consolidation (1909-1922), the Inconsistency Between the Year and Volume Numbers, and the Lack of a Volume XVIIIThe first volume of Actas Dermo-Sifiliográficas begins with the papers presented at the first meeting of the society held on May 6, 1909. This inaugural meeting was held at the College of Physicians of Madrid, which at that time was located on the third floor of number 1 Calle Mayor, just off Puerta del Sol in Madrid.9 It was not by chance that the Society and Actas were founded in 1909. In 1908, Azúa had been joined in the Hospital de San Juan de Dios, where he had worked for over 20 years, by 2 young physicians who would play key roles in the founding of the Society and Actas: the first was Sainz de Aja and the second was another young physician called José Sánchez Covisa (Fig. 3).32 The energy of these 2 young dermatologists together with Azúa's experience was the perfect combination for setting up a journal and founding “la dermatológica,” as the new association was called by its members at the time.

The traditional bordered portraits of Covisa and Sainz de Aja commemorating their graduation from the University of Madrid. These portraits are currently displayed in the main hall of the College of Physicians in Madrid. These 2 young dermatologists arrived at Hospital de San Juan de Dios on August 1, 1908, joining Azúa, whose experience stretched over 20 years at the hospital. Their meeting led a year later to the founding of the Spanish Society of Dermatology and Syphilology (now the Academy of Dermatology and Venereology) and to the start of the Society's journal Actas Dermo-Sifiliográficas.

The first volume of Actas Dermo-Sifiliográficas is quite atypical because it comprises only 2 issues (May-June 1909 and July 1909) which, between them, amounted to 116 pages. However, these 2 issues from 1909 were never assigned a volume number and were never considered as a volume, but merely referred to as Year 1. The reason for this was the short period that remained of the academic year when the meetings of the Society commenced. The first issue of Year 2 is dated October-November 1909, although it may not have actually come out until early 1910, at least this is suggested by a footnote on the first page of the issue.33 This fall issue in 1909 continues the page numbering of the 2 issues published before the summer. The first volume of Actas therefore covers the few gatherings that took place during the 1908-1909 academic year and all of those held in the 1909-1910 year. From the start, this gave rise to a discrepancy between the year and volume numbers, which is already apparent on the cover of volume II (Fig. 5). This inconsistent numbering of years and volumes was not corrected until the academic year 1926-1927, when the nineteenth year of publication coincides with volume XIX. However, the correction entailed the suppression of volume XVIII in the numbering of Actas (Fig. 2). It is not clear whether this adjustment was intentional because it coincides with the change in the name of the Society (which became the Academy) and the enactment of new statutes that were approved at the end of 1925 and took effect in 1926.

Cover pertaining to the second volume of Actas Dermo-Sifiliográficas published during the 1910-1911 academic year. This cover shows the discrepancy between the publication year, which corresponded to the academic year, and the volume numbering. This situation persisted until 1926, and may have given rise to confusion in references citing early articles published in Actas.

This inclusion of the output of the first 2 academic years in a single volume, the suppression of volume XVIII, and the publication by academic rather than calendar year in the early decades of the journal (until 1957) gives rise to confusion in the citation of the early articles published in Actas because many old reference lists cite first the calendar year, followed by the publication year of the issue (rather than the volume number), and lastly the number of the first page of the article being cited. The difference between calendar years and academic years also created problems for the Academy. Under the Society's original bylaws, the treasurer's report had to be submitted by calendar year and, since the main economic activity was precisely the publication of the journal, the early treasurer/administrators complained about the problems this caused in the balance sheet. After the Civil War, when Francisco Daudén Valls became treasurer, the accounting year was changed to coincide with the academic year. However, in January 1957, when the publication schedule was changed to correspond to the calendar year, the discrepancy arose once again and the accounting had to be changed back to calendar years.

The First Officers, and Actas Dermo-Sifiliográficas in the Earliest Bylaws and the Statutes of the AcademyThe covers of the early issues reveal that Azúa held the post of editor, with Covisa as editorial secretary and Miguel Serrano as administrator (because he was the treasurer of the Society). The officers and operation of Actas Dermo-Sifiliográficas have always been governed by the association's statutes and bylaws. However, the earliest version of these bylaws still extant is dated December 1925. The original typewritten copy of this document stamped with the original seals is still kept in the AEDV's current headquarters. There were almost certainly earlier versions because there is at least one reference to article 5 of the bylaws in the Society's membership list dated February 1910,33 but the original document has been lost. A copy of these original bylaws may still exist in the historic documentation dating back to 1909 held in the archives of the College of Physicians in Madrid since this was the Society's first official domicile.

The first mention of an editorial board came at the beginning of volume V (1913-1914). At that time, it comprised Sainz de Aja as editorial secretary and Eleuterio Mañueco Villpadierna, for whom no position was specified. The 1917-1918 academic year brought some minor changes in the board. Azúa continued to figure as editor and Sainz de Aja as the editorial secretary, but Julián Sanz de Grado appeared as administrator and treasurer and Covisa was listed as a board member along with Mañueco.

The first written set of rules governing the functioning of Actas Dermo-Sifiliográficas of which we still have a copy is dated February 10, 1922.34 A few months earlier, the journal had published a resolution proposing the reorganization of the journal; the resolution was passed by the Society at a meeting held on June 10, 1921. It is possible that this was the first time that the operation of the journal had been regulated in writing because the first paragraph says, “We, the undersigned, who have been appointed to draft a short code of bylaws to regulate the operation of the journal Actas Dermo-Sifiliográficas, propose that the General Assembly approve the following articles.” This introduction was followed by 3 articles. The first identified Actas as the journal of the Society and specified 3 types of content: extracts from meetings, original articles, and a section with reviews of other journals. Article 2 specified the editorial board, which was to be composed of 3 ex officio members (the president, secretary and treasurer of the Society) and 3 associate editors elected by the corporation, 1 of whom was to be appointed to the post of executive editor by the Society. Article 3 describes the functions of each of these positions in greater detail.

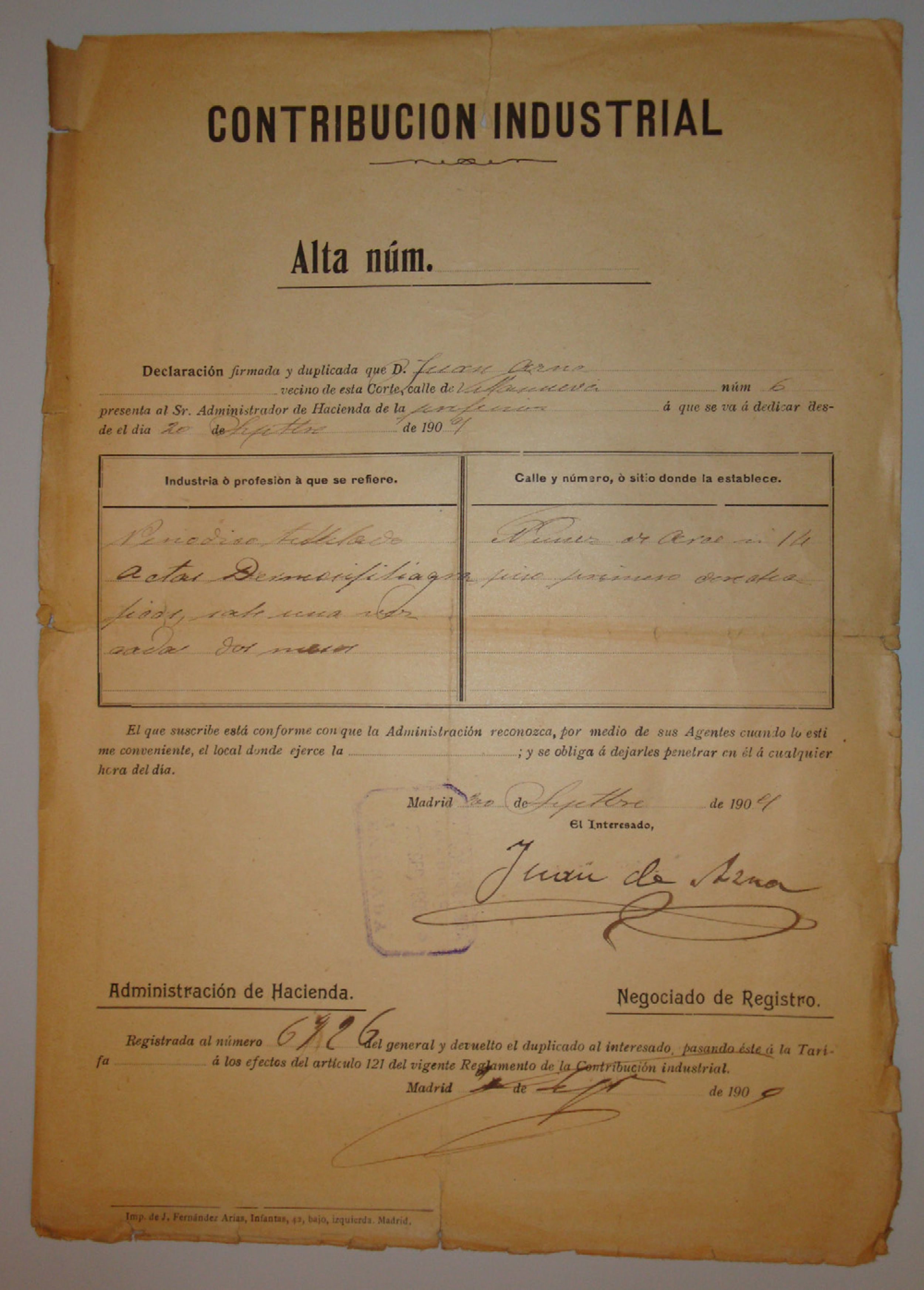

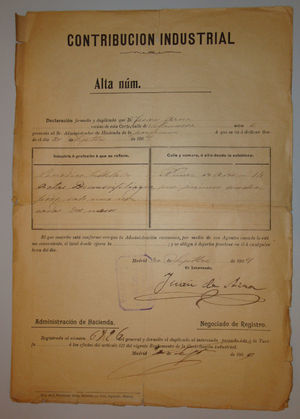

Chapter III of the 1925 bylaws deals with “the journal of the Academy and its editorial board.” It comprises articles 10 to 16 and established that the association's president would be the editor-in-chief of the journal and the vice-president would be the executive editor. The treasurer of the Academy continued to occupy the post of administrator of the journal, and in the early years the address that appeared on the cover of Actas was always the treasurer's. The first treasurer was Miguel Serrano de la Iglesia, whose address at number 14, Calle Nuñéz de Arce, first floor, was the journal's first official home. The same address appears on the form registering the journal for the purpose of industrial taxes, the oldest document relating to the journal still on file at the AEDV's current offices (Fig. 4). The 1925 bylaws also specified that there would be 4 recording secretaries.

Document certifying the registration of Actas, noting payment of the industrial tax, signed in September 1909 by Juan de Azúa. This fragile piece of paper is the only surviving document from 1909 conserved in our Academy. The address shown was the home address of the first administrator, Miguel Serrano.

While we do not know precisely how many copies of the first issue were printed, we can estimate that the initial run may have been approximately 100 copies if we take into account that the Academy had just over 70 members in February 1910 (including the 30 founding members, the numerary members, residents, and national and international supernumerary members) and that additional copies were needed to supply official libraries, institutions, and government offices. The first printer used by Actas was the Imprenta y Librería Casa Vidal located at number 98 Calle de Atocha. We also know that the publication of the first issue together with the purchase of 1000 envelopes to post copies to subscribers cost a total of 354 pesetas, and that the cost of publishing the second issue was 311.85 pesetas.35 From 1912 onwards, Actas was printed by a company with the evocative name of Alrededor del Mundo (around the world). This firm was located at number 82 Calle de Ferraz, a location coincidentally very close to the current offices of the AEDV. From the cover of the early issues we see that the journal initially came out 5 times a year (Fig. 5), that is, there were bimonthly issues during the academic year to coincide with the schedule of scientific meetings.

The print run must have increased gradually as membership grew. In the final years of Azúa's time as editor-for-life of the journal, nonmember subscribers started to be listed in the annual report, giving us a better idea of the journal's real readership. This information was not reported in the early years.

Foremost Topics in the First Period: Syphilis, Allergy, Psychogenic Dermatoses, Pseudoepithelioma, and Physical TreatmentsThe journal's predominant focus in the early years was clearly syphilis. Furthermore, its launch coincided with the discovery by Ehrlich and Hata of Salvarsan, a drug also known as 606. The different applications, reactions, and efficacy of this drug and its derivatives and successors, including Neosalvarsan (914) and sodium Salvarsan (1206), filled many pages of the early volumes of Actas.

Some of the dermatology papers by Azúa himself are noteworthy, such as one on allergy to the paraphenylenediamine in hair dyes29 that was discussed in the series of articles commemorating the journal's centenary year.12 In that paper, Azúa made advances in the study of allergic contact dermatitis at a time when the concept of allergy was not yet clearly defined. It is a very difficult task to summarize the journal's content during this period or to select the most noteworthy articles because any such selection must inevitably reflect personal bias. However, my attention was particularly attracted by some of Azúa's papers on psychogenic dermatoses, in which he reveals a keen intuition about the close relationship between the skin and mental health. In one he reported 4 cases of pathomimesis,36 another is a skillful description of 4 cases of glossodynia,37 and in 1912 he made a new contribution with a report on a very complex case of pathomimesis.38 Heras-Menzada22 reviewed a few of these articles in the section commemorating the centenary published in 2009. This era also produced several articles on the subject of one of the most original contributions of Azúa and Spanish dermatology to the world literature of the specialty, namely, pseudoepithelioma or vegetative pyoderma.39–41 Azúa had previously published an occasional paper on the subject of this new diagnostic entity in collaboration with the pathologist Claudio Sala Pons.42 Azúa and Sala's contribution to world dermatological literature has been reviewed elsewhere.43

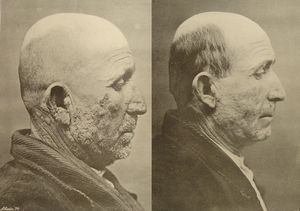

The early issues of Actas also featured innovative physical treatments, such as the use of dry ice. An article by Nonell and Serrano44 was illustrated with 2 photogravures, one of the first examples of the classic before and after images that enjoy such success in conferences today (Fig. 6). This era also featured the first articles on dermatologic radiotherapy45 and UV phototherapy.46

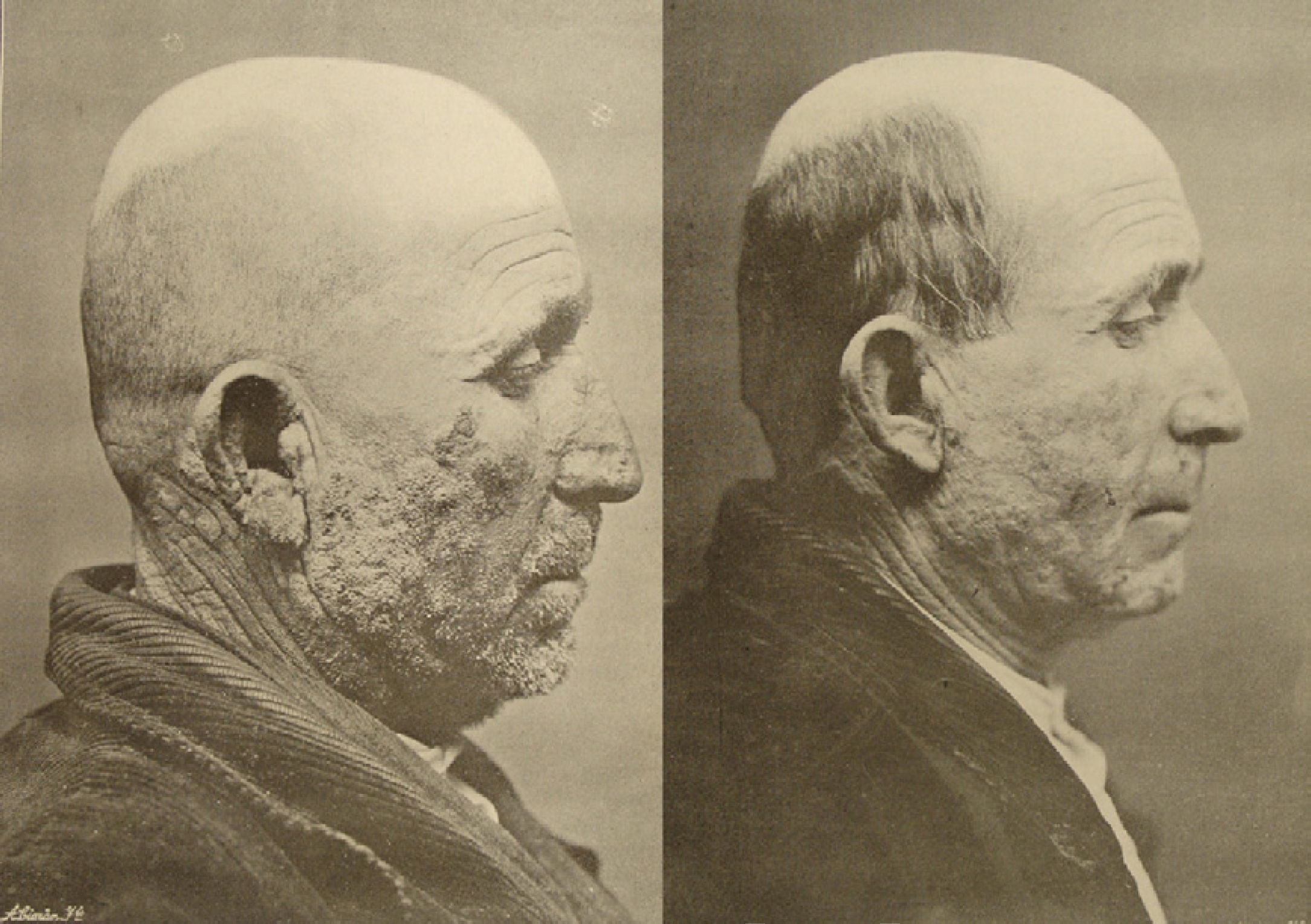

These 2 photogravures were used to illustrate an article by Nonell and Serrano44 in 1910 on the use of cryotherapy in the treatment of lupus vulgaris. In addition to the historical value of the pictures themselves, they are also one of the very first examples of the before and after photographs that now figure so prominently in our congresses. They are also interesting because they illustrate one of the pioneering articles on cryotherapy in European dermatologic literature.

In 1922, Actas received its first written rules of editorial procedure that we know of34 and its founder Juan de Azúa died. Both events are of historical and documentary interest, but the structure, content, and style of the journal remained essentially unchanged. The April-May issue in 1924 included a posthumous article by Azúa commenting on classification and statistics in dermatology47 which was in fact the speech he had drafted for the occasion of his election to the Real Academia Nacional de Medicina (Royal Spanish Academy of Medicine). He never gave the speech because he suffered a stroke that left him with severe hemiplegia. The article is an excellent summary of Azúa's experience and his philosophy for the specialty, which was based on consideration of both pathologic findings and clinical course.

The June-July issue of volume XIV (1923) contained papers by Queyrat, Malvoz, Halkin, and Ravaut that had been presented in July of that year at the Second French Congress of Dermatology and Syphilology in Strasbourg, providing evidence that the journal was becoming well-established and gaining an international reputation. A number of papers by Spanish dermatologists working in hospitals of note in other countries also appeared. One was a 1929 article on mycosis by Eduardo de Gregorio, who was working at the time in Raymond Sabouraud's department in the Hôpital Saint Louis in Paris. The author's time in this hospital had been funded by a grant from the Junta de Ampliación de Estudios e Investigaciones Científicas, a government institution charged with promoting scientific education and research in the early part of the 19th century.48

In December 1925, the Sociedad Española de Dermatología y Sifiliografía was renamed the Academia Española de Dermatología y Sifiliografía. The real reasons for this change in the name have never been clear, but there are 2 theories. The first is that the change was made for merely bureaucratic reasons and was required by a new law governing associations promulgated under the Primo de Rivera dictatorship. This is suggested by a note appended to the statutes when they were published in Actas.49 The second paragraph of Article 5 of the new law specified that no association could function legally without being registered. This does not, however, properly explain why the name had to be changed from Society to Academy. The second theory, which has been passed down by oral tradition in Hospital de San Juan de Dios in Madrid, is that a member, Felipe Sicilia Traspaderne, had for reasons unknown registered the name of the society in the trademark registry in his own name, thereby obliging the Society to change its name in order to register. As evidence against this hypothesis we can adduce Sicilia's active participation in the Academy's sessions and the fact that he published regularly in Actas throughout his long professional career and even after retiring from his position as a physician in Hospital de San Juan de Dios in 1955. When he retired, Sicilia's lifetime achievement was honored at a special meeting of the Academy and no mention was ever made of this allegation.50 Whatever the case, Actas Dermo-Sifiliográficas was not involved in this debate and did not need to change its name. In fact, the Academy still retains the documents attesting to the registration of its ownership of the name Actas Dermo-Sifiliográficas as a trademark. On December 31, 1925, Covisa was the editor-in-chief, Sainz de Aja the executive editor, and José Barrio de Medina, José Fernández de la Portilla, Augusto Navarro Martín, and José Gay Prieto were the recording secretaries. The administrator was Miguel Forns Contera.

On January 21, 1927, Covisa presided over his last meeting of the Academy as president in this period and Sainz de Aja succeeded him as president and therefore editor of the journal. The executive editor was Miguel Fernández Criado with Julio Bejarano as secretary. The recording secretaries were Barrio de Medina, Laureano Echevarría Ledesma (due to the resignation of Fernández de la Portilla on March 11, 1927), Navarro Martín and Gay Prieto. Forns Contera continued as administrator. At a later date, Juan Ontañón Carasa replaced Echeverría, and Emilio Enterría Gaínza replaced Navarro Martín. The next important change occurred on January 7, 1931, when Sainz de Aja resigned from his position as president of the Academy and was succeeded by Bejarano, who thus became the new editor-in-chief of the journal. The vice-president and executive editor during this period was Julio Bertoloty, and Fernández de la Portilla was the secretary. Forns Contera continued as administrator and treasurer, and the recording secretaries were Juan Ontañón Carasa, Enterría Gaínza, Jesús Muñuzuri Galíndez, and Javier Tomé Bona. One important change that occurred during this period was the expansion of the publication schedule to 9 issues per year, with monthly publication from October to June. This new schedule started with the 1928-1929 academic year (Fig. 7). From this time onwards, the journal was generally printed on gloss paper, although during the Spanish Civil War and the years following the war lower quality paper was once again used for a period.

The 25th anniversary of both the Academy and Actas Dermo-Sifiliográficas made 1934 an especially important year. The anniversary was celebrated at a meeting of the National Academy of Medicine presided by 2 physicians: Verdes Montenegro, who represented the government of the Spanish Republic, and Bejarano as the president of the dermatology Academy. The secretary of the Academy, Fernández de la Portilla, presented a comprehensive review of the first 25 years. However, despite the close connection between Actas Dermo-Sifiliográficas and the Academy throughout their history, he made almost no specific references to the journal in his presentation. This meeting later became known in the history of Spanish dermatology as the First National Congress of Dermatology.

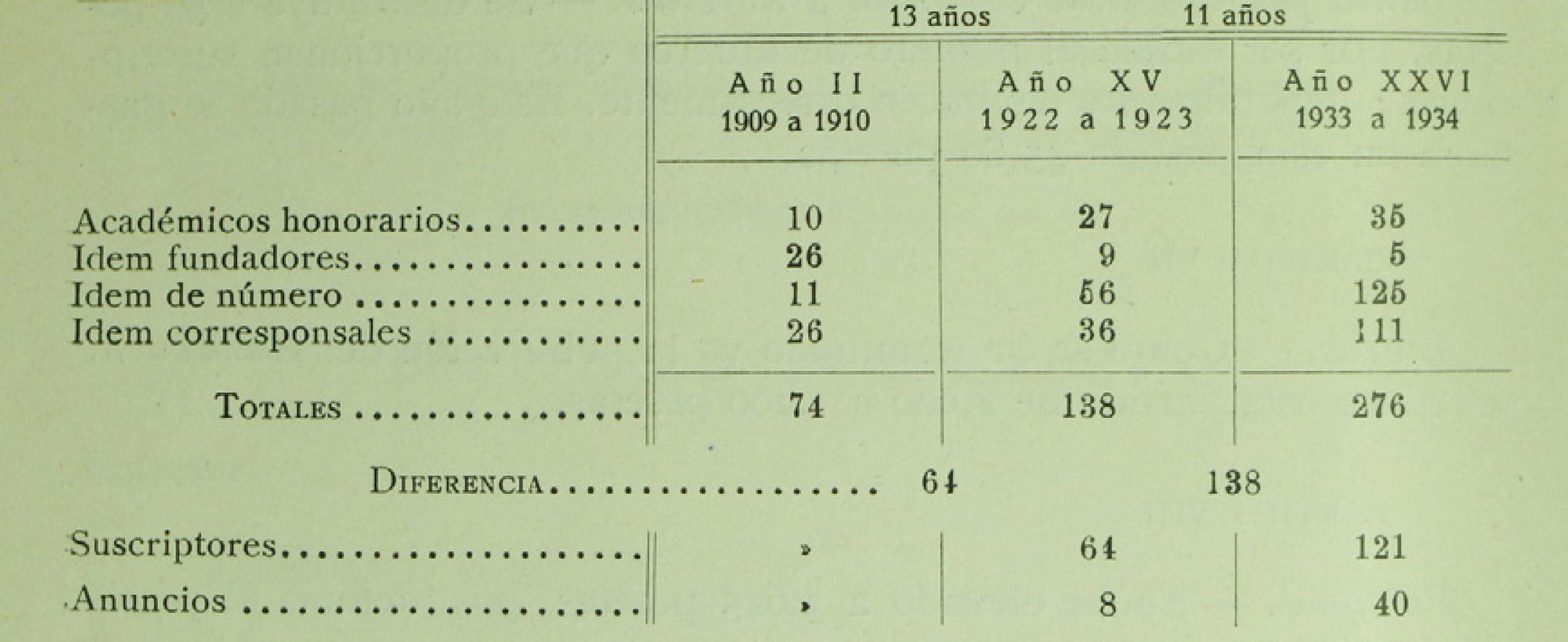

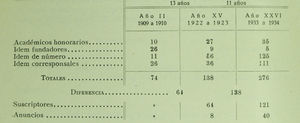

In accordance with the bylaws, elections for the officers of the Academy and board members of Actas were held once again on October 1, 1934. Covisa remained as president and editor-in-chief, and Fernández de la Portilla was elected to the position of vice-president of the Academy and became executive editor. Ricardo Bertoloty became general secretary, and Eduardo Isla Carande, Miguel Salinas, Luis Vallejo Vallejo, and Gómez Orbaneja were elected as recording secretaries. Forns Contera continued in his post as administrator. During the Ordinary General Meeting held in October 1934, he presented a table showing the changes in membership and circulation figures between 1909 and 1934 (Fig. 8). Taking into account copies sent to the various types of members and subscribers, the total would come to 397 copies. Adding copies for gifts and exchanges with other journals and libraries, the total print run must have been around 500 copies. During the 1935-1936 academic year, the Academy's board of directors and the editorial board of Actas remained unchanged, with the exception of the replacement of Forns Contera by Serviliano Pineda Martín, who took over the post of treasurer of the Academy and administrator of the journal.

This table was presented by the treasurer Miguel Forns as part of his annual treasurer's report in 1934. It gives us an idea of the growth in membership and subscribers in the early years. The number of honorary Academy members increased over the years with each successive appointment. The founding members, logically, decreased in number. The numerary members (those resident in Madrid) had greatly increased in number as had the supernumerary members (corresponsales, those resident outside of Madrid). At the end of the table we see the category of nonmember subscribers to Actas.

The program of the Second National Congress of Dermatology and Syphilology (Granada, June 8-10) appeared in the April 1936 issue of Actas. The June issue contained a brief overview of the congress, including the titles of the papers given by invited speakers and the 74 free papers presented. However, the papers and main presentations were never published in Actas because in mid-July 1936 the military coup took place that began Spain's sad Civil War.

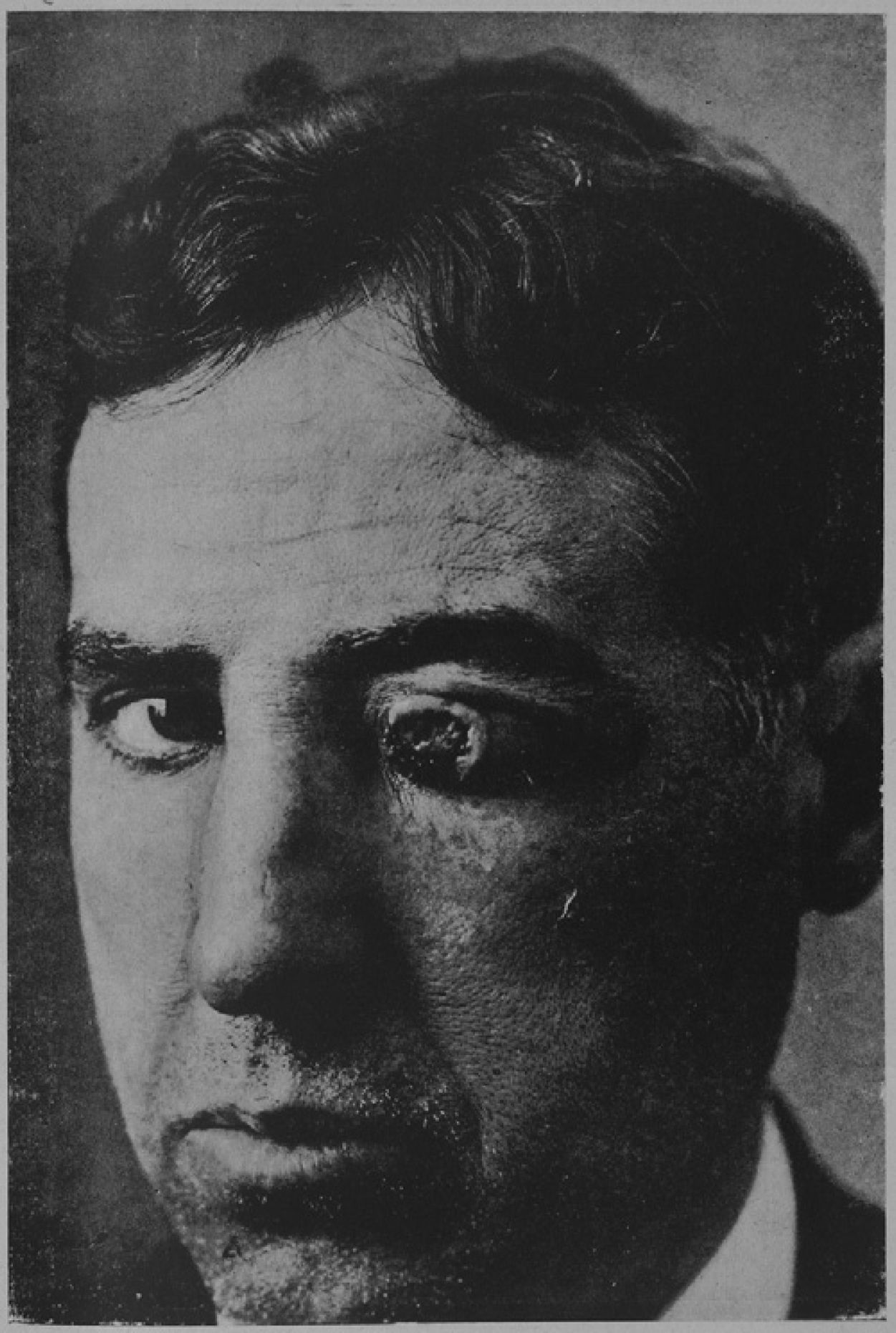

Predominant Topics Between 1922 and 1936, Chancriform Pyoderma, and Color Illustrations in ActasIn the years leading up to the Civil War, venereology continued to be a major topic in the journal despite the introduction of Salvarsan, or perhaps precisely because of this drug. The limitations of Salvarsan and its side effects led to the development of new compounds that incorporated arsenic, silver (silver-Salvarsan), or other metals (such as bismuth salts). These products were described in a number of papers published in Actas and presented at Academy meetings. One of the most important Spanish contributions to the dermatological literature during this period is the description of chancriform pyoderma contributed by Covisa and Bejarano (Fig. 9). The first extensive article on the subject was published in the April-May issue of 1927 (volume XIX).51 Two cases in children had previously been reported at a meeting held in Hospital de San Juan de Dios on March 28, 1924.52 Chancriform pyoderma is an ulcerous cutaneous lesion with an indurated base located in a genital—or extragenital—site. Its clinical presentation closely resembles a chancre, including the characteristic regional lymphadenopathy. Even the histology of the lesion may be similar to that of a chancre, but the results of both serologic studies and treponemal tests are always negative. The importance of this clinical entity, somewhat forgotten today, must be seen in the context of the era before the advent of antibiotics, when syphilitic chancres were a common finding in routine consultations and chancriform pyoderma caused by common bacteria could give rise to confusion. In May 1934, the same authors published a second review article on the subject, with 5 clinical illustrations and 2 histologic images.53 This Spanish contribution to the world dermatological literature has been reviewed in detail.54

Photogravure from 1934 that illustrated one of the many articles describing the various forms of chancriform pyoderma that Covisa and Bejarano published in Actas Dermo-Sifiliográficas. The clinical presentation of the disease was unusual. The lesions, which were genital or extragenital (as seen in this illustration), mimicked a syphilitic chancre but had a different etiology. The importance of this clinical entity, practically forgotten today, must be seen in the context of the great prevalence of syphilis at that time.

The use of color in Actas was the exception until relatively recently. The first color photogravure of a clinical presentation that I have found appeared in the October 1935 issue, although several histologic photogravures had been published in color just a few months earlier. This first clinical image in color (Fig. 10) shows a case of tuberous sclerosis reported by López Ibor, who was the full professor of medicine in Valencia and physician for the provincial mental hospital.55

Color illustrations were very rare in Actas Dermo-Sifiliográficas until relatively recently. This image, which dates from 1935 and was one of the first, appeared in an article by López Ibor,55 director of the mental hospital in Valencia. It shows, albeit with the poor resolution of early color images, the facial angiofibromas of a patient with tuberous sclerosis.

As Roustán and Suárez Martín56 have pointed out, the Civil War caused a terrible rift in Spanish dermatology that mirrored the division in civil society. Apart from the direct impact of the conflict, a secondary consequence of the war for dermatologists was the loss of several leading figures in the specialty. The conflict also opened up the possibility for other, perhaps less brilliant, dermatologists to prosper and gain renown in an environment that was favorable to them and hostile to possible competitors.

Little is known today about the relations between dermatologists who supported one side or the other in the war. An account written by Fernández de la Portilla in 1940 would seem to indicate that physicians on both sides displayed a reasonably respectful attitude towards one another, at least outwardly57: “... I am responsible for investigating the regrettable behavior of some red physicians towards their comrades in prison who were in great need of aid and support. It is only fair to note that such behavior has been exceptional and that most Spanish physicians, whatever their own position or personal beliefs, have honored the sacred oath of our profession.” However, subsequent events belied Fernández de la Portilla's elegant phrases when the weight of the victor's reprisals was brought to bear inexorably on the losing side, as we shall see below.

Actas Dermo-Sifiliográficas was not unaffected by the vicissitudes of history at this time. Publication ceased between July 1936 and September 1937—the only time the journal has failed to keep its regular appointment with Academy members and subscribers. In September 1937, it resumed publication from the territory held by General Francisco Franco and without the assistance of any of the dermatologists loyal to the Republic. An editorial signed by Sainz de Aja in Burgos in September 1937 greeted readers and promised a regular publication schedule, a promise that probably not even the editorial board themselves believed they could fulfill. This board included Sainz de Aja as the honorary president of the Academy in Burgos, Gay Prieto, who was professor of dermatology in Granada, and de Gregorio in Zaragoza. After the November 1937 issue, these 3 dermatologists were joined by a group of 41 contributors all located in the parts of Spain under the control of the Francoist forces. The administrator during the war was Máximo Muñoz Casas from Burgos.

The issues of Actas published during the 1937-1938 publication year are slightly smaller than those from before the outbreak of war. The journal was printed in Granada from 1937 until the beginning of 1940. The effort made by Sainz de Aja, de Gregorio, and Gay Prieto to reestablish the journal's publication no matter what is evident in the first issues of this volume. Since no Academy meetings were taking place during this period, the pages of the journal were filled with hurriedly written original articles as well as a large section on dermatology news and a review of content from other journals, both written by Sainz de Aja, who also included an obituary of Edward Ehlers. De Gregorio was also an active contributor, and Gay Prieto took responsibility for the editorial tasks. The second issue of this wartime volume, corresponding to November 1937, featured an article by Raoul Bernard from Brussels on occupational skin diseases, a paper that seems surprisingly up-to-date even today.

The masthead of all of the issues in the 1937-1938 volume included the inevitable reference to the “Second Triumphal Year,” a phrase that appears beside the date and year of publication. Favorable references to the military authorities in the Francoist zone appeared in some sections. Madrid, Catalonia, and the whole east coast of Spain simply ceased to exist during this period. Nonetheless, and with survival as the sole aim, the journal continued to be published even in the throes of war, an accomplishment that distinguishes it among Spanish biomedical journals. Actas even managed to continue to attract advertising.

In the 1938-1939 academic year, the journal regained a degree of normality, returning to its prewar format and the number of pages and articles it had in 1935-1936. The masthead continued to feature the “triumphal year” tagline, which in early 1939 was changed to “the year of victory.” In addition to Sainz de Aja, de Gregorio and Gay Prieto, the other officers in 1939 were Fernández de la Portilla and Navarro Martín. Fernández de la Portilla had moved to the Francoist zone in January 1938 and was to play a leading role in the postwar Academy. He became vice-president in 1936 and president thereafter. He was even appointed by the authorities to the presidency of the College of Physicians of Madrid. In this post, he was responsible for the investigation of doctors who wished to exercise their profession or teach medicine, as required by the new authorities as part of a purge of undesirable elements, and for executing the resulting barring orders.58 Page 62 of this volume (XXX) provides, for the first time, information on the journal's operation, including the exact print run of 500 copies. Articles from abroad also begin to reappear, reflecting the editorial board's efforts to regain prestige within the troubled European dermatology community of the late 1930s. As proof of its gratitude, the journal published the profiles of several of these authors. The first physician to be the subject of such a profile was Oppenheim of the Wilhelminenspital in Vienna, whose article on the treatment of infantile vulvovaginitis with Uliron was published in October 1938.59 This was followed by articles by Pignot, Nohara, and Gougerot and profiles of these physicians.

Over half of volume XXX—from March 1939 onwards—is dedicated to the Third National Congress of Spanish Dermatologists, which was held in Seville shortly before the end of the war (February 18-20, 1939). Muñuzuri and José Salvador Gallardo undertook the preliminary organization of this event, which was held in the city's Academy of Medicine. Gallardo represented Seville's dermatologists and formed a local organizing committee. The March 1939 issue of Actas carries a dedication to the “Head of State, Caudillo of the Fatherland and Savior of Spain” (Fig. 11) in a departure from the traditional apolitical stance of both the Academy and the journal.

Dedication to General Franco that appeared in the March 1939 issue of Actas. This was one of the few instances in which the journal departed from its apolitical position, a stance of paramount importance to the publication's founder, Azúa. However, this submission to authority may have helped to make it possible for the journal to continue publishing and to obtain paper, which was in exceedingly short supply after the war.

In retrospect, and from a common sense standpoint, this identification with the new regime on the part of the Academy was not entirely negative since it allowed both the Academy and the journal a certain amount of freedom of action and freedom to engage in scientific activities. This was the view was put forward by Fernández de la Portilla in his speech at the inaugural session of the Third Congress, who said, “We have been authorized to resume our scientific and institutional activities with no restrictions other than those set down in our own bylaws and to freely elect those individuals who will represent us.” In the event, the Academy and its journal were not exempt from the strict government control imposed after the war, and we know from notes published in later issues of the journal that these optimistic predictions were not entirely borne out in practice. After the war, the Academy's board of directors was appointed by an official order of the Ministry of National Education dated October 5, 1939.60 The freedom to elect their own board of directors was later restored to the members of the Academy on February 12, 1943 by another official order issued by the same ministry.

After the war, the Academy made use of its members with ties to the new regime to support its legitimacy and maintain continuity. Besides Sainz de Aja, the honorary president, and Fernández de la Portilla, acting president of the Academy and editor of Actas, another important figure at the Third Congress was Gómez Orbaneja, who had become recording secretary in 1936 and was secretary of the congress.

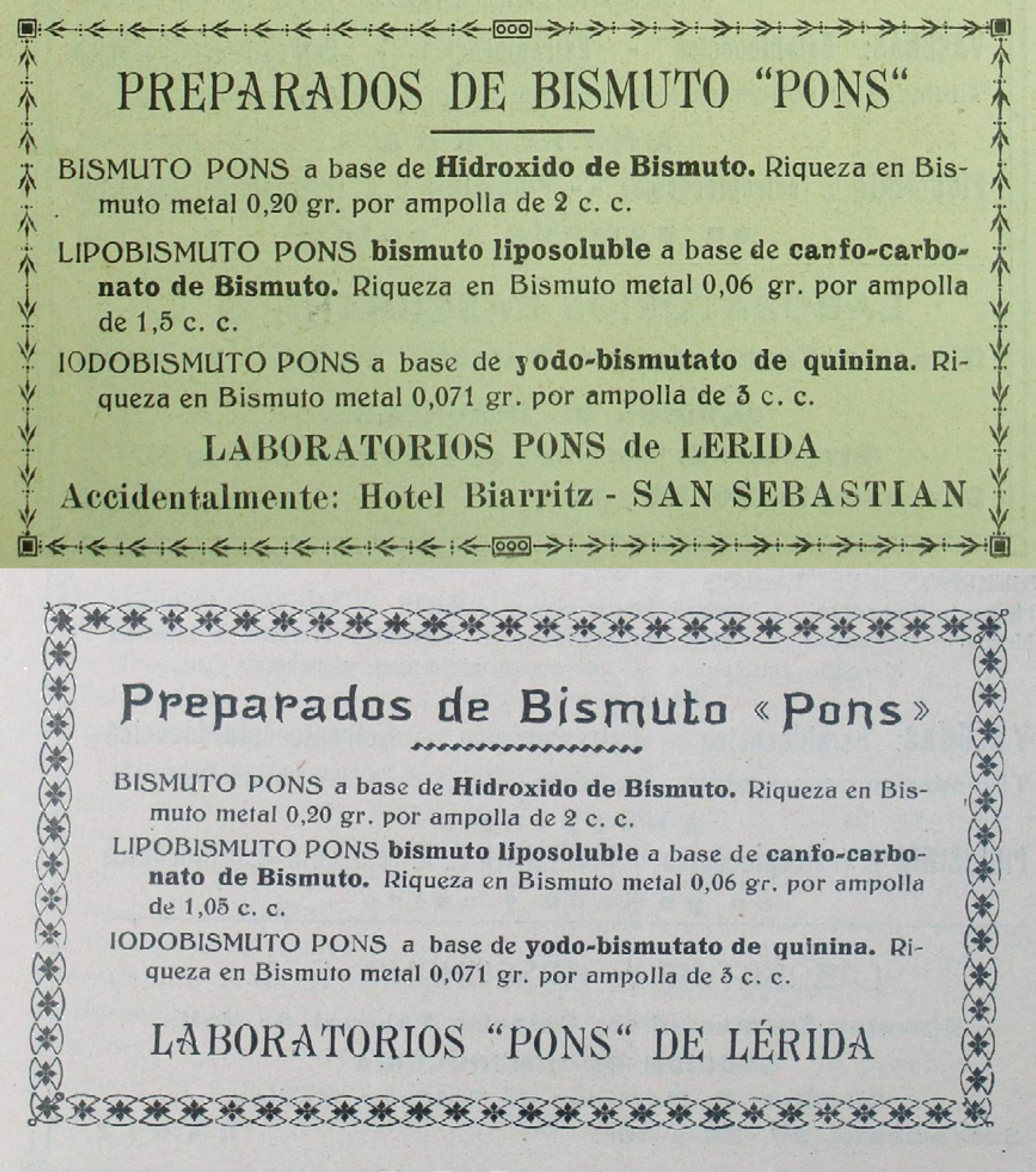

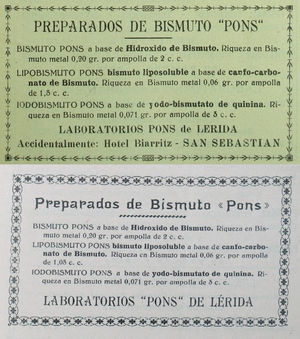

Volume XXIX of our journal had opened with the words of Sainz de Aja written from Burgos, and the last issue in volume XXX, published in May 1939, closed with a brief note by the same author, who had returned to Madrid following the end of the war. Anecdotal evidence of the end of the conflict can also be found in the advertisements, namely the return of Laboratorios Pons to its native city of Lleida. Laboratorios Pons regularly advertised preparations of bismuth salts, a now obsolete and long forgotten treatment used in the management of syphilis. At the beginning of the 1939-1940 academic year, the war now over, this company's advertisements once again mention their usual domicile in Catalonia instead of the “temporarily located in... San Sebastian” that had been a feature of its advertisements in Actas throughout the war (Fig. 12). This firm will always be part of the anecdotal history of Actas because its advertisement regularly occupied the bottom half of the table of contents page from the time the journal resumed publication in October 1937 until March 1958.

Bismuth salts were an alternative to Salvarsan in the treatment of syphilis during the first half of the 20th century. The advertisement shown in the upper panel of the figure appeared in the first issue of Actas to appear after the outbreak of war (October 1937). It advertises 3 products made by the Pons laboratories of Lleida. The advertisement contains the indication that the company has been temporarily relocated to the Hotel Biarritz in San Sebastian. In the lower panel we see the same advertisement after the war ended in 1939, at which time this indication no longer appears.

The Civil War led to the disappearance from the family of Spanish dermatology of many of its members. Some went into exile (Covisa and Bejarano being the most well known in this group); others were taken prisoner in the Republican zone (for example, Luis Díaz Villarejo), executed by the Republicans (Julián Sanz de Grado and José Quintana Duque—both soldiers), gave their lives “for God and their Country” (Alfredo Martí Escorihuela), or were executed by Francoist forces (including Ramón Hombría Íñiguez, who was at the time in charge of Azua's venereal clinic in Cordoba). After the war, many physicians were barred from practice or persecuted in their professional medical activities and as teachers. This group included notable figures such as Manuel Hombría Íñiguez—brother of Ramón and head of the dermatology laboratory in the Madrid faculty of medicine—and Covisa, who was punished by suspension from his post and retention of his salary for 5 years.61 Pineda Martín, Vallejo Vallejo, and Enterría Gaínza were also sanctioned in a grotesque trial in the course of which the prosecution even purged the Galician Roberto Novoa Santos, a brilliant professor of General Pathology at the Universidad Central who had died on December 9, 1933, some 3 years before the outbreak of the war.62 The war also left some enigmas, such as the case of Fernández Criado, the prewar vice-president, who does not appear on membership lists after 1936 but nonetheless reappears as a deceased member in 1952. Today serious, well-documented articles about Spanish dermatology during the Civil War are starting to appear,56,63 but there are still areas where our knowledge is scant and dark corners into which light needs to be shed, because while it is true that we must turn the page and move on to another chapter in our history, we first need to read what was written on that page.

Prominent Topics Between 1937 and 1939: the Sulfa DrugsThe December 1937 issue of Actas includes an article by Sainz de Aja on sulfonamides, one of the most important advances in medicine of the 1930s. These antimicrobial agents had already been discussed in European scientific circles during the Spanish Civil War. Gerhard Domagk (Fig. 13) first published his work on sulfa drugs in 1935, and his discovery represented the most important advance in dermatologic therapy since the discovery of Salvarsan in 1909.64 The first of these new sulfur-based chemotherapeutic drugs found to have a clinical application was sold under the commercial name of Prontosil (Fig. 14). It rapidly became the first-line treatment for severe streptococcal, staphylococcal, and gonococcal infections of the skin, dermatoses for which there had previously been practically no really effective remedy. Sainz de Aja reported his experience with combined intramuscular and oral Prontosil in 2 cases of severe pyoderma and 1 patient with an inguinal lymphogranulomatosis, describing excellent results. Uliron, another sulfa drug soon appeared on the market. Both were produced by Bayer in Leverkusen, Germany. The January 1938 issue of Actas began with an in-depth article by Manuel Garriga on these drugs,65 and many of the articles that followed (in volume XXIX, 1937-1938) also dealt with these compounds. Even today, sulfa drugs like cotrimoxazol continue to be useful antimicrobial agents. Moreover, sulfonamides are also found in very diverse groups of drugs we do not normally associate with them, such as the sulfones, and in diverse pharmacologic compounds, including diuretics (thiazide and furosemide), uricosurics (probenecid), oral antidiabetic agents (tolbutamide and carbutamide), and some psychopharmacologic drugs.66

This portrait of Gerhard Domagk illustrated the biographical sketch by Lana Martínez published in Actas when this distinguished scientist was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1939 for his discovery of sulfa drugs. From 1939 until his death Domagk was an honorary member of the Spanish Academy of Dermatology and Sifiliografía.

Prontosil and Uliron were two of the first and most prominent sulfa drugs. The incorporation of these drugs into the therapeutic arsenal of dermatologists made it possible to control many venereal infections (especially gonococcal infections) and some pyodermas. The advent of penicillin a few years later struck an almost decisive blow to syphilis. Between them, these 2 remedies gave rise to a difficult situation for many venereologists who made their living almost exclusively from attending patients with these infections.

The infections, trauma, injuries, and sexually transmitted diseases that always increase during wartime only served to highlight the efficacy of these new chemotherapeutic agents. In 1939, Domagk was awarded the Nobel Prize for Medicine for his discovery, but the Nazi authorities forced him to refuse the prize and he was even arrested by the Gestapo for a week because of the award. The reason for this surprising reaction was the Nazi's annoyance about the 1935 Nobel Peace Prize being awarded to the German Carl von Osietsky, a decision seen by the regime as a provocation and unwonted interference in the internal affairs of Germany. After this event, the Nazis obliged all German citizens to refuse the prestigious award. Domagk finally collected his prize in 1947 after the Second World War, although he was not given the monetary award that normally accompanies this honor because of the time that had elapsed.67 The March 1940 issue of Actas included a biography and portrait of this German scientist written by Francisco Lana Martínez, a lecturer at the University of Zaragoza.68 From this time until his death in April 1964, “Gerardo” Domagk figured as an honorary member in the annual rolls of the Academy.

The Postwar Period, Shortage of Paper and Other Resources, Officers and Board MembersVolume XXXI of Actas, which began in October 1939, still opens with the “year of victory” tagline to the masthead. The first item is a profile of Professor Schreus of the Düsseldorf Academy of Medicine, who had contributed to the May 1935 issue. His contribution to this volume was its lead article, dealing with the use of radiation therapy in the management of angiomas.69 The previous 5-member editorial board and the long list of associate editors that first appeared during the Civil War remained unchanged except for the appointment of Daudén Valls as treasurer. The Academy held an extraordinary general meeting on June 15, 1939, and regular scientific meetings resumed in October of the same year. Recording secretaries were again elected; these posts were occupied by Miguel Salinas, Félix Contreras Dueñas, Antonio Ugalde Urosa, and Joaquín Urrutia Salsamendi. By March 1940, the journal had returned to normal operation. A note from the board of directors printed in the March issue announced the journal's return to its usual Madrid offices. Publication was resumed with the authorization of the Director-General for the Press. The same note also relates the difficulties that Gay Prieto and his group in Granada had overcome to continue the publication of the journal, mentioning their efforts “to obtain printing materials, find paper, and produce photogravures..., tasks that are already hard in peacetime and so much more difficult in times of war.”

The scarcity and high cost of paper and the general financial difficulties that plagued Spain during the postwar period also left their mark on the journal. Footnotes in several issues noted that authors would henceforth have to pay for offprints. In the minutes of a board meeting, recorded in a book still kept in the current offices of the AEDV, we can read the summary of a meeting held on November 8, 1939, which reports, “Mr Portilla gave an account of the steps being taken to acquire the paper necessary to publish the journal during the current academic year. He reported that he is encountering difficulties because of the current scarcity of paper and it was agreed that a deputation should be sent to the Government Minister, if this should become necessary, to explain the unquestionable usefulness of the publication of the proceedings of the Spanish Academy of Dermatology and Syphilology, which is the only scientific society currently active and the only one that remained active throughout the war.” The paper shortage was particularly severe in 1942 because of the lack of both Spanish production and supplies from Europe. The issues published during that year are printed on paper that is so thin that the words on the opposite side of the page are visible through the paper. At one point, the paper shortage became so acute that pages 434 and 738 of volume XXXIII contain an announcement that authors should henceforth reduce the length of their manuscripts and the number of illustrations submitted. This situation persisted as late as the end of 1945, when another major announcement appeared informing readers that “as long as the current shortage of paper and electrical power flow (sic) continues to limit the number of pages in the journal, the length of articles submitted for publication may not exceed 30 double-spaced typewritten pages and a maximum of 6 illustrations.”

The recording secretaries in 1940-1941 were Contreras Dueñas, Luis Álvarez Lowell (son of Álvarez Sainz de Aja), Jose Luis Agustín Sancho, and Francisco Martínez Torres. The other officers did not change. Volume 34 (1942-1943) is of particular historical interest because it could be called the “volume of portraits.” Included were the photogravures of the following people: Xavier Vilanova i Montiu on the occasion of his appointment as the first professor of dermatology at the University of Valladolid; Gay Prieto following his move from Granada to take up a professorship in Madrid; Sainz de Aja, as the director (decano) of the Beneficencia Provincial de Madrid and Director of Hospital de San Juan de Dios; Jaime Peyrí, reinstated as professor in Barcelona; Salvador Gallardo, president of the Academy's Andalusian section and associate professor in the faculty; Antonio Martínez Navarro Zanón, president of the Valencian section; de Gregorio, president of the Basque-Navarre-Aragon section and director of the Dispensario de Zaragoza; and Fernández de la Portilla of Valencia, who died on 4 May, 1943, the first professor of dermatology to obtain his post by sitting official competitive examinations. Actas Dermo-Sifiliográficas dedicated a lengthy section to his memory, an obituary only comparable to that of the journal's founder Juan de Azúa. This can be explained by Fernández de la Portilla's great political weight during the postwar period.

By 1943, the print run had increased to 600 copies, and in April of that year Daudén Valls proposed raising it to 700 because there were insufficient copies to meet the demand.60 The editorial board for volume 35 remained essentially unchanged, except for the appointment of Sainz de Aja as editor owing to the death of Fernández de la Portilla in May 1943 and the appointment of Antonio López Villafuertes as recording secretary to replace Agustín Sancho. New statutes and bylaws were published in the November 1943 issue and duly submitted to the Director-General of Security for approval.70 There were no important changes in the organization of the journal except that the position of executive editor would now be occupied by the secretary-general of the Academy rather than by the vice-president. This meant that Antonio Cordero Soroa became executive editor of Actas at the close of the 1944-1945 academic year. The annual subscription was set at 60 pesetas and single issues cost 10 pesetas each. This made Actas Dermo-Sifiliográficas one of the most expensive periodicals in Spain at the time.

In volume 38 (1946-1947), the only change in the editorial board was that Gerardo Jaqueti replaced López Villafuertes as recording secretary. A brief note in a section entitled “important announcements,” which appeared in this volume, deals with a topic of great concern for the journal, that of bibliographic citations, which had not previously been standardized. The announcement reads as follows: “We also request that bibliographic references should include, in the following order, the author's surname, first name initials, article title, journal title, year, volume, and page.../.... Authors are requested to diligently check all the references and proper names cited before submitting a manuscript.”71

José Gay Prieto and José Gómez Orbaneja, Editors of Actas in 1947 and 1951, RespectivelyToday, the era of larger-than-life figures and fratricidal battles would appear to be a thing of the past. A classic example of such a battle was the confrontation between 2 major figures, José Gay Prieto and José Gómez Orbaneja, and their respective disciples. Actas Dermo-Sifiliográficas bore witness to the fray, and numerous commentaries and criticisms coming from both sides were published in its pages. The rift was also reflected among the journal's board members, although there was always a degree of consensus. In volume 39 (1947-1948), Gay Prieto was editor-in-chief and Tomé Bona executive editor. The recording secretaries were Gerardo Jaqueti, Julio Rodríguez Puchol, Emiliano Lobato Martín, and Antonio García Pérez. An innovation introduced in the October 1947 issue was the inclusion of an alphabetized bibliographic index at the end of the journal. At that time, the contents of Actas were organized into the following 3 sections: theoretical contributions (reviews and extensive articles); clinical papers (including abstracts of the papers presented to the various sections of the Academy and other scientific activities); and scientific information and current events, which included miscellaneous news, the bibliographic indexes mentioned above, commentaries, and obituaries. The new organization of the journal led to a notable improvement in the quality of the review articles, some of which may, even today may still be of some use, not merely of historical interest.

The absolute record for number of references in a single article during the first 50 years of Actas is held by Tomé Bona, head of the dermatology department in the Clínica del Trabajo del Instituto Nacional de Previsión, who included no less than 506 references in a review about the skin diseases affecting painters and allied trades.72 The same volume also included supplement 9 of Actas, containing papers in Portuguese presented by Portuguese authors at the congress held in May 1946 in Valencia, although the supplement did not appear until 2 years after the event.

Volume 43 (1951-1952) once again records changes in the officers of the Academy by virtue of which Gómez Orbaneja was elected president and thus became editor-in-chief of Actas, Manuel Álvarez Cascos became executive editor, and the recording secretaries were Marcelo Laporta Medía, Ramón Morán López, Carlos Daudén Sala, and Pedro Álvarez Quiñones. In line with what had become the established custom, Daudén Valls remained in the post for treasurer and administrator for another term.

Sainz de Aja, Editor Once Again in 1955; the Introduction of Summaries; and Publication by Calendar Year Starting in January 1957At the beginning of the 1955-1956 academic year, elections for the officers of the Academy were held for the 4-year term from 1955 to 1959. Sainz de Aja was once again elected president and became editor of Actas. Luis de la Cuesta Almonacid became secretary-general of the Academy and executive editor of the journal. The new recording secretaries were Daudén Sala, Antonio Ledo Pozueta, Joaquín Soto Melo, and Nicolás Ballesteros Blázquez. Once again, Francisco Daudén Valls continued for another term as treasurer and administrator.

A new feature, which appeared in the late 1940s and early 1950s only to disappear again for a time, was the publication of summaries, particularly of review articles. These abstracts, or summaries, appeared at the end of the articles and were published in French or English as well as Spanish. In the case of articles written by Vilanova, professor of dermatology at the university in Barcelona, the summaries always appeared in 4 languages (Spanish, French, English, and German) and enormously facilitated the international projection of his work, making coverage of it possible in the journal review sections of foreign publications.

The December 1955 issue contained an interview section created by Daudén Sala. The first interview featured Juvenal Esteves, one of the most important historical figures in Portuguese dermatology.73 Subsequent issues featured Sainz de Aja74 and Oscar Gans.75 Each interview was accompanied by a caricature of the interviewee drawn by Daudén Sala himself. The original drawings were kept and are on display in the offices of the AEDV. These interviews were recently remembered by their author in an article published in Actas.26

The final and most important formal change in the first 50 years took place in 1957, when the journal's volumes began to follow calendar years instead of academic years, bringing it into line with most other scientific publications. This change had been included in an amendment of the statutes and bylaws approved in the fall of 1955 and it gave rise to a short hiatus in publication between June 1956 and January 1957. However, the scientific meetings and activities of the Academy continued normally during that period, although reports appeared only later in the volume that started in January 1957.

Reestablishing the Old Local Chapters in Granada and Valencia as the Andalusian and Valencian Sections and the Creation of the Catalan and Basque-Navarre-Aragon SectionsThis period saw the implementation of an important change that had begun in the 1930s, namely, the organization of the Academy into sections, leaving behind once and for all the organizational model based on numerary and supernumerary members. The growing number of dermatologists in Spain, the diversification of the specialty, and the presence of prominent dermatologists working throughout the country were all factors that made this decentralization necessary. During the Second Republic, local chapters had been set up in Granada and Valencia.

The Granada chapter was created through the efforts of Gay Prieto, at that time a young professor of dermatology in the city. The chapter's inaugural meeting had been held on March 12, 1933 and was attended by Bejarano as president of the Academy. The Andalusian section created after the war was based on members of the earlier Granada chapter, now joined by Muñuzuri and Salvador Gallardo, 2 distinguished dermatologists from Seville. A dermatology society had previously existed in Seville, but I have no further information about this group. The idea of creating an Andalusian section had been discussed during the Third Congress of Spanish Dermatologists held in 1939, but this section was not formally constituted in Seville until April 25, 1940. Volume 32 of Actas (1940-1941) opened with papers from the first scientific meeting of the new section held on August 16, 1940 in the assembly room of the Diputación de Cadiz. Papers arising from this section meeting occupy a large part of volume 32 of Actas.

After Granada, the next local chapter to be set up was that of Valencia. The first clinical gathering of the Valencian chapter was held on February 24, 1934, although the official inaugural meeting took place later on March 18, 1934 in the meeting room of the university's department of medicine. It was also attended by Julio Bejarano, president of the Academy. We still have the records of this original chapter in Valencia, and even some of the names of the recording secretaries, including Silverio Gallego Calatayud, Carlos Faura, and Emilio Aliaga Ferris. The Valencian section was founded after the Civil War on the basis of the preexisting local chapter and the official inauguration took place on October 16, 1940. Martínez Navarro Zanón, José Esteller, and Faura de Mirás played important roles in starting the group, and the first scientific meeting was held on December 9, 1940 in the College of Physicians in Valencia.

The organization of dermatology in Catalonia proved to be a little more complex. The Barcelona section—as the Catalan section was initially called—held its inaugural meeting on February 8, 1941 and was organized by Jaime Peyrí. The creation of this section had been agreed on during the Fourth National Congress in Barcelona in October 1940. A Catalan Dermatology Society had existed in Barcelona before the Civil War and, according to Tuneu Valls,76 had been active at least since 1925 in and around Peyrí’s dermatology department. This group went on to become affiliated with the Barcelona Academy of Medical Sciences and, according to Villarejo, the editor of Ecos Españoles de Dermatología y Sifiliografía, was relatively inactive in 1930.77 The minutes of a meeting of the board of directors of the Academy held on April 12, 1935, states that “Dr Covisa gave an account of his conversations with the Catalan dermatologists and the proposal to create a chapter of this Academy in Barcelona, and remarked on the cordial reception he received during these meetings.” However, as far as I have been able to determine, this fusion or integration of the Catalan dermatology group never took place.

In 1950, some years after the creation of the Catalan section and some months after the death of Peyrí, the Association of Dermatology and Syphilology of the Academy of Medical Sciences of Barcelona was also founded. The driving force in the creation of this organization was Vilanova, although the first president was Santiago Noguer Moré. From references that can be found in the pages of Actas, this new organization was to be more concerned with organizational, collegiate and professional questions than with the mainly academic and educational areas that would continue to be the concern of the Catalan section of the Spanish Academy.78

The youngest of the Academy's early sections was that of the Basque Country, Navarre and Aragon, which was set up under the presidency of de Gregorio and held its first meeting in Zaragoza on June 21, 1941. The activity of these 4 sections contributed greatly to the scientific content of Actas Dermo-Sifiliográficas. They each had their own organizational structure and recording secretaries. The Madrid meetings of the Academy were redefined as the Central section.

Hispano-Portuguese Dermatology, the Iberian-Latin American College of Dermatology, and Relations With the United StatesThe broad outlines of the future of the Academy and its journal in the postwar era had already been sketched out in a speech by Sainz de Aja at the closing ceremony of the Third National Congress held in Seville in February, 1939: the return to normal scientific activity for the Academy, including its role as a publisher, the reestablishment of the regional chapters as sections, and the forging of closer ties with Portuguese dermatologists. With the rest of Europe embroiled in the Second World War, Hispano-Portuguese relations—always encouraged by Sainz de Aja—were seen as an imperative after 1940. The 2 countries of the Iberian peninsula joined forces; both were ostensibly neutral in the war, both suffered from international isolation, and both had similar types of government. An early example of contact appears in the May 1940 issue, which opens with a portrait and biographical sketch of Luis Alberto de Sá Penella79 and a case report of a patient with pseudoxanthoma elasticum written by de Sá Penella with Juvenal Esteves of Lisbon.80 This article marked the beginning of a long and fruitful relationship between Spanish and Portuguese dermatologists that resulted in a number of joint congresses and the publication in Actas of many original articles written in Portuguese.

The first joint Hispano-Portuguese Congress was held in Valencia in 1946 (May 16-19).81 This congress was also the Sixth Spanish National Dermatology Congress as it took place after the fifth congress held in Bilbao (September 5-10, 1942). The Second Hispano-Portuguese Dermatology Congress was proposed a number of times and finally took place in Lisbon in 1950 (May 30-June 4).82 The Spanish papers given at this meeting were published in the December 1950 issue of Actas, which also contained the announcement of the First Iberian-Latin American Congress of Dermatology and Syphilology to be held in Rio de Janeiro in 1950 (September 24-30).83 The College of Iberian and Latin American Dermatology had already been created earlier in 1948.84

The Third Hispano-Portuguese Congress was held in Santander in 1954 (September 13-17). At this event, an index of the articles published in Actas between 1909 and 1953 was distributed courtesy of Industria Farmacéutica Cantabria. The list had been compiled by Navarro Martín. The second session at this Congress was on the topic of rheumatic skin diseases. The speakers were Luis Azúa Dochao, professor of dermatology in Zaragoza, Gómez Orbaneja, the Academy's president, and Bernardo López, the first professor of dermatology in the Faculty of Medicine in Cadiz. Lengthy summaries of all 3 papers were published in Actas.85–87 It was agreed at this congress that the following Hispano-Portuguese Congress would take place in Coimbra in 1958.

Another good occasion to break Spain's international isolation after the victory of the Western democracies and the Soviet Union over the European fascist regimes was the celebration in Madrid of the Sixth International Leprology Congress in 1953. Gay Prieto and Contreras Dueñas both played leading roles in the organization of the event, and it was at this congress that consensus was reached on the classification of leprosy still in use today. Actas Dermo-Sifiliográficas dedicated the first pages of the October 1953 issue to this congress, which coincided with the Second Meeting of the Iberian and Latin American College of Dermatology in Madrid. The Third Iberian-Latin American Dermatology Congress took place in Mexico City in 1956 (October 21-27). The fourth edition of this Congress was held in Lisbon in 1959 (May 5-7), just before the Hispano-Portuguese conference in Lisbon that year (7-9 May), and only shortly before the Academy celebrated the 50th anniversary of its founding in Madrid on 18 and 19 May.88

In the 1950s, Spain was also working to strengthen ties with the United States. For obvious strategic reasons the United States—now the dominant power in the West—perceived Franco's staunch anti-communism to be useful in the prevailing climate of the Cold War. The most obvious historical evidence of this rapprochement was the signing on September 26, 1953 of the bilateral Pact of Madrid, which included a defense agreement that opened the way for American military bases in Spain. Thanks to its newfound American friend, Spain ended its period of international ostracism under a dictatorship and with its economy in shreds. In practice, the pact implied international recognition of the Francoist regime and marked the end of any possibility of Spain regaining a normal democratic government at that time. These historic events also had a small, albeit probably less well known, corollary in the world of dermatology; the news section in the January 1957 issue included an official invitation extended by Dr J.R. Webster, secretary and treasurer of the American Academy of Dermatology and Syphilology, to Luis de la Cuesta Almonacid, his counterpart in the Spanish Academy of Dermatology and Syphilology, to attend the American Academy's 15th annual meeting in December 1956 in Chicago.89

The Introduction of Penicillin to Spanish DermatologySulfa drugs continued to be one of the predominant topics in the postwar journal. In 1940, advertising started to appear for Pyramidon, the most popular of these drugs and, like Prontosil and Uliron, also a product of Bayer. Reports of allergies and resistance to these drugs, and their side effects, began to figure on the pages of Actas and studies were published.

Epidemics of scabies, pyoderma, ringworm, and parasites during the postwar period provided another common area of concern. The hardships, drought, and famine that followed the war also gave rise to a number of articles on malnutritional skin diseases of all kinds, such as noma, caused by vitamin and protein deficiencies. Reports also appeared on the cutaneous effects of lathyrism from poisoning caused by excessive consumption of grass pea flour.

However, the innovation that undoubtedly occupied center stage in this era and was probably the most important therapeutic contribution to dermatology and medicine worldwide in the first half of the 20th century, was the introduction of penicillin coinciding with the end of World War II.