The ossifying fibromyxoid tumor (OFMT) was originally described as a small benign tumor of the subcutaneous tissue. It is formed of small cells arranged in cords and nests in a fibromyxoid stroma, covered by a bony capsule.1 However, recent publications have reported histologic findings of malignancy associated with metastatic disease.2 There is controversy regarding the histologic origin of the tumor. Despite initially being considered to be distinct from schwannian or cartilaginous tumors,1 based on ultrastructural and immunohistochemical characteristics (positivity for protein S-100), more recent proteomic and genetic analyses support a neuronal or myoepithelial origin.3,4 In the last decade, the idea that malignant OFMTs do not exist has been proposed, as they do not satisfy the traditional histological description, and could correspond to other malignant soft tissue tumors.5

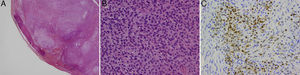

In the last 20 years, 2 cases of OFMT have been identified in our hospital, one on the scalp of a 55-year-old man the other on the hand of a 46-year-old man (Fig. 1). The tumors were painless. Histology of the excisional biopsies were consistent with the classic description of OFMT: well-defined capsule; areas of fibrosis formed of laminae of uniform, ovoid cells with round nuclei in a hyaline stroma; other areas of myxoid appearance with lower cellularity; and moderate diffuse positivity for protein S-100 (Fig. 2). The surgical margins were not extended in either case. No signs of local recurrence or metastases have been detected after follow-up of 18 years and 21 months, respectively.

Histology images. A, The ossifying fibromyxoid tumor with its characteristic, incomplete capsule of lamellar bone; hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), original magnification ×2. B, Monomorphic epithelioid cells with small nucleoli and clearly distinct borders; H&E, original magnification ×40.C, Immunohistochemistry showing diffuse positivity for protein S-100; original magnification×20.

This tumor typically affects men, and the mean age at presentation is 50 years. It usually arises in the proximal regions of the limbs, most commonly the lower limbs.1,3–6

Immunohistochemistry closely reflects the controversy regarding the histogenesis of the tumor. The origins that have been postulated with greatest emphasis are Schwann cells (because of the existence of well-developed, duplicated basal lamina and positivity for protein S-1007) and cartilage (due to the presence of irregular cell borders with small projections and intracellular microfillaments with positivity for S-1001). Other authors have suggested a myoepithelial lineage based on ultrastructural findings,4 or neuronal lineage due to positivity for CD56, a neural adhesion molecule, and for EAAT4, a neuronal glutamic acid transporter.3

Cytogenetic analysis of this type of tumor focuses attention on 2 genes, INI-1,3 a tumor suppressor gene, and PHF1,8 which codes for a protein that, among other functions, regulates the activity of the polycomb-repressive complex 2, which silences genes responsible for development. Dysregulation of this complex, secondary to changes in these or other adjacent genes, has been suggested as a mechanism of development of OFMTs.

In 1995, Kilpatrick9 was the first to describe the existence of OFMTs with a malignant behavior, associated with atypical morphological findings. Folpe and Weiss6 identified criteria predictive of an aggressive or malignant behavior. Subsequently, Miettinen5 rejected the existence of malignant OFMTs, stating that the majority of those tumors did not satisfy the classic description of OFMTs and could be better classified as other types of sarcoma. Graham,3 continuing the work initiated by Folpe, validated their classification on finding that the malignant subtype was associated with a more aggressive behavior during follow-up.

A biologically aggressive behavior was also investigated in the largest series of OFMTs. Folpe6 detected local recurrence in 18% and metastases in 16%. Miettinen,5 including only typical OFMTs, reported local recurrence in 22% and no cases of metastasis. Finally, Graham3 reported local recurrence rates of 4.3% and metastasis in 6.5%, considering only malignant OFMTs. Grouping the data from those series, the metastatic risk of the typical variant is less than 5%; this indicates that, even if benign histological characteristics are observed, OFMT can give rise to metastases.

The scarcity of OFMTs recruited in the past 20 years in our hospital, given that the catchment population is close to 1 million, would appear to be related to a diagnostic vision closer to that of Miettinen than to Folpe and Graham. Thus, tumors that do not fit the typical description of OFMTs, and that showed characteristics of malignancy, were classified as low-grade sarcomas rather than as malignant OFMTs. This could explain the absence of recurrence in either of our 2 patients, despite having performed excisions with narrow margins.

In conclusion, OFMT is a rare disease, whose epidemiology may be biased by the diagnostic considerations of each pathology departament regarding atypical and malignant variants. Despite showing benign characteristics, these tumors can present aggressive behavior, and they should not therefore be classified as benign, but rather considered as tumors of intermediate malignancy.

We would like to thank Drs. José Juan Pozo-Kreilinger, Adrien Yvon, and Estefania Alonso-Rodríguez for their close collaboration, which made this study possible.

Please cite this article as: Hernández-Godoy J, Casado-Sánchez C, Landín L, Rosell AA. Diagnóstico histológico del tumor fibromixoide osificante: 2 casos en los últimos 20 años. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2015;106:772–774.