From the moment the Olavide Museum opened its doors in 1882 until its content was packed up around 1965 and lost sight of for a time, it underwent a succession of changes. Some of those changes cannot be fully documented now because the archives of the Provincial Council (Diputación) of Madrid were lost during the Spanish Civil War. The museum was initially housed in Hospital de San Juan de Dios, in the neighborhood of Atocha. Because this hospital treated mainly venereal diseases, much of the information we have about it comes from newspapers or magazines of the period, and their accounts were often sensationalistic. When a large number of the museum's wax figures were rediscovered, along with a great many accompanying documents, in December 2005, the material allowed 3 sculptors—Zofío, Barta, and López Álvarez—to be identified. Case histories corresponding to the figures were also among the papers found. As a result, the truth about certain legends associated with the museum, the sculptors, and the patients could be unraveled. Among the patients whose stories were brought to light was one referred to as the boy with generalized tinea favosa, or crusted ringworm.

El Museo Olavide, desde su inauguración en 1882 hasta su desaparición en 1965, ha sufrido múltiples vicisitudes, algunas de ellas no contrastadas de forma oficial debido a la desaparición durante la Guerra Civil de la documentación existente en la Diputación de Madrid. El museo estaba localizado inicialmente en el Hospital de San Juan de Dios en Atocha. El hecho de que en este hospital predominasen las enfermedades venéreas hizo que muchas «noticias» que hoy tenemos sea a través de periódicos o revistas de la época, en muchos casos con cierto carácter sensacionalista. Con la recuperación de las figuras del museo en diciembre de 2005 encontramos abundante documentación que sirvió para que se pudiera identificar a los 3 escultores, Zofío, Barta y López Álvarez, así como historiales clínicos de las figuras. Con ello se pudo desmitificar leyendas existentes en torno al museo, a los escultores y a los enfermos, una de estas es la del «muchacho de la tiña favosa».

The history of the Olavide Museum, with its sculpted models and figures,1,2 is rich in legends and anecdotes passed along in hospital corridors and retold in other medical circles at the end of the 19th century. Medicine at this time still wavered between charlatanism and science: in these social and medical circles those who thrived often practiced well outside the bounds of science, yet attained fame while promulgating irrational notions.

The Olavide Museum maintained close ties with Hospital San Juan de Dios in Madrid, and most of the wax models created were based on cases treated in this facility, which served prostitutes and those with skin diseases (leprosy, tuberculosis, forms of ringworm) from the time it opened until the middle of the 20th century. Such patients were barred from other hospitals at the time.1

Given the type of patients admitted, the hospital's location was set apart from other centers and even from Madrid's social life itself. Dark legends about brothels and secret diseases, mercury cures and shame grew up around it. Some legends were told about patients, others about the staff who attended them. Many appeared in newspaper accounts, magazines, or even in books as important as Pío Baroja's Arbol de la Ciencia (Tree of Knowledge),3 in which the protagonist, Andrés Hurtado, visits the hospital as a student. Hurtado, a character identified with Pío Baroja, tells a story about a physician's cruelty to a cat and a prostitute. According to a PhD thesis by del Río,4 the doctor in the anecdote corresponds to the historical figure of Dr López Cerezo.

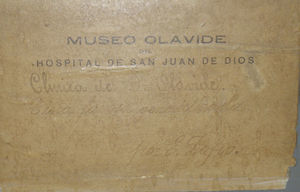

Of all these legends and tales, one in particular caught our attention, that of the boy—or girl—with generalized favus. This patient is the subject of one of the museum's most emblematic wax models. Restored in 2009, this complete figure (Fig. 1) had been found when a group of boxes were opened in 2005. The box was in good condition and the figure was intact inside a glass case, although some of the colors had faded. There was also a label (Fig. 2) naming the sculptor (Zofío) but giving no further information that could be used to date the work.

Enrique Zofío Dávila (1835–1915?) was the most important of 3 sculptors who worked at the museum; José Barta and Rafael López Álvarez were the others.2 Zofío, who created over 80% of the models found thus far, worked in the military hospital system and began to create models for its medical anatomy museum in 1864. When he retired in 1911, he was working at the museum of the Hospital Militar de Madrid-Carabanchel. We cannot document an association between Zofío and Hospital de San Juan de Dios or its museum, but we do know that he was a friend of Dr José Eugenio Olavide and that the entire medical staff of the hospital held him in respect as a creator of wax moulages.2

Taking this information as our starting point, we reexamined the figures and searched through the available documents for relevant information. Two articles, one in ABC (dated December 14, 1966)5 and another in the magazine QUÉ (April 6, 1978),6 were cited in the 1990 doctoral thesis of Padrón Lleo.7 These articles reported interviews with one of the Olavide Museum's other modelers, López Álvarez (1898–1987). This colorful character collaborated with Barta on 23 figures and completed a single figure on his own.

When interviewed, López Álvarez referred to himself as the last sculptor to head the Olavide Museum5,6 and as the creator of the figure this article is about, stating that he ordered it to be packed for storage when the museum was closed in 1967. One of the articles5 gave further information about the young patient with generalized favus: Around 40 years ago, a 12-year-old boy was admitted to Hospital San Juan de Dios with generalized favus, in a condition that left him truly monstrous. He stayed in the hospital several months and, as his case was quite interesting, we made a model to illustrate it. The boy was later cured and we heard no more about him [until] a letter from America—from New York—suddenly arrived. The boy had become a millionaire and wrote to ask if the model we had made of his skin was still in the museum. When we replied that it was, he asked if he could buy it at any price so it would serve as a reminder of those difficult years.

However, that figure—one of two depicting favus (the other patient was a woman)—still remain with the collection. We shall now learn why.

Until recently we assumed all the foregoing information to be true, although doubts were raised because dates given were inconsistent with what was known of the life of Zofío, the artist named as creator of the figure we are concerned with here.

As information about the museum came to light, we found many more facts that did not square with the story told by López Álvarez. We cite some examples:

- 1.

The figure in question was made by Zofío according to the original label (Fig. 2), which was found along with the glass-enclosed model.

- 2.

Zofío seems to have died sometime between 1915 and 1917. Although the exact date of death has not been documented thus far, the approximate one is inconsistent with López Álvarez's statement in 1966 that Zofío came to Hospital San Juan de Dios “about 40 years ago.”

- 3.

An inventory of the museum figures showed that Zofío produced 9 depicting favus lesions appearing on the scalp, arm, and nails. One figure—which we understand to be the one in Fig. 1—modeled the patient's entire body.

- 4.

We found 2 contemporary publications referring to the inauguration of a museum at the hospital, one in La Época (December 28, 1882)8 and the other in El Día (December 26, 1882).9La Época described the scope of the museum as relating to medicine, surgery, and histochemistry. El Día referred to it as the provincial anatomy museum and gave a detailed description of its content, specifically mentioning “a reclining figure of a 10-year-old girl with generalized favus.” An excerpt from the story in the evening edition follows:

Among the pieces that are outstanding for their accurate coloring and precise depiction of these diseases, we mention a reclining figure of a 10-year-old girl with generalized favus, [and also models of] collections of erosive lupus lesions on the face, and epithelial sores also on the face. All the models show the lesions in their true size, having been created from casts. Worth noting because of the rarity of the conditions depicted are a model of molluscum pendulum and another showing a malignant form of generalized exfoliative herpes. Thirty-seven watercolors illustrating interesting cases, and belonging to Mr Castelo, are also included in the collection.

Finally, we were able to locate the case notes (Fig. 3) for the child with generalized favus: patient number 132, who was assigned bed 17 in ward 12. The description–which coincides with all the aforementioned data (date of admission, age, clinical picture, diagnosis, course, treatment, and death)–is translated as follows: Generalized Favus.—No. 132, ward 12, bed 17, clinic of Dr Olavide. Patient E.G.G. of Madrid, 8 years old, a girl, of a lymphatic-nervous temperament and passive constitution, was admitted to this clinic on September 20, 1879. No family history. Our information about the patient's personal medical history comes from her mother, who reports her daughter had measles when she was younger, after which she became delicate of health, had a poor appetite, remained very pallid, and grew very slowly; all of this was undoubtedly the effect of profound anemia. Some 6 months [before she was brought to the clinic], an eruption appeared on her trunk and extremities, later on the scalp; the yellowish crusts of the eruption converged, and rather than resolving, they became more numerous, obliging admission to this hospital. Current status.—Crusted favus lesions form large plaques that affect all surfaces of the patient's body and are particularly numerous on the head and sacral and gluteal regions. These crusts are elevated over the surface of the skin and are the result of the convergence of concentric layers; the crusts have the appearance and consistency of stratum corneum and are of a uniform whitish-yellowish color. Surrounding the crusts are red inflammatory halos, and when a crust breaks off the underlying skin is depressed, pale, and appears to be atrophied. The patient is extremely weak, showing signs of anemia and lymphatism. Treatment.– Poultice of rice flour on the crusts, which fell off with the help of full-body emersion in a warm bath. Once the crusts fell off, hair was systematically removed from the scalp, which was then rubbed with an ointment of corrosive sublimate (15 cg to 30g of salve). An ointment made from juniper oil was applied to other regions of the body with this type of lesion. From the start of treatment, the girl was also given cod liver oil (30g with 50mg of iron iodide); when after 3 days she could no longer tolerate the oil, this treatment was replaced with 100mg of iron in 30g of simple syrup. On October 10 the juniper oil was replaced with a coal tar ointment. The patient improved considerably under this treatment but died on January 6, 1880, after developing acute albuminuria. Palacios

This information provides sufficient grounds for concluding that the so-called boy with generalized favus of the figure was really of a girl around 9 years old.

We also conclude that the legend, or anecdote, so charmingly told by the museum's last sculptor, Rafael López Álvarez, is just one more of the many tales that circulated around the Hospital de San Juan de Dios and the Olavide Museum.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Conde-Salazar Gómez L, Heras Mendaza F. Tiña favosa, historia de una leyenda. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2015;106:383–386.