Bullous pemphigoid (BP) is the most common chronic autoimmune subepidermal bullous dermatosis, occurring mainly in the elderly. It is characterized clinically by a pruritic polymorphous skin rash that typically arises on the abdomen, the flexor surfaces of the limbs, the neck, axillas, and groin. Initially the lesions are often excoriated, erythematous, eczematous, and/or urticarial. Blisters usually then develop on normal or erythematous skin, giving rise to crusted erosive areas that heal without scarring. The diagnosis is confirmed by the demonstration of deposits of immunoglobulin (Ig) G or of the C3 component of complement on the epidermal basement membrane, and the presence in the serum of circulating IgG antibasement membrane zone antibodies against antigens BP-180 and BP-230. Numerous variants of BP have been described, with a broad spectrum of clinical manifestations.1–3

A 32-year-old woman, with skin phototype VI, with no personal or family history of interest, was seen in dermatology outpatients for the appearance of a highly pruritic, widespread skin rash that had developed 3 weeks earlier. The patient was not taking any medication or using topical products, had not been sunbathing, and reported no associated systemic symptoms.

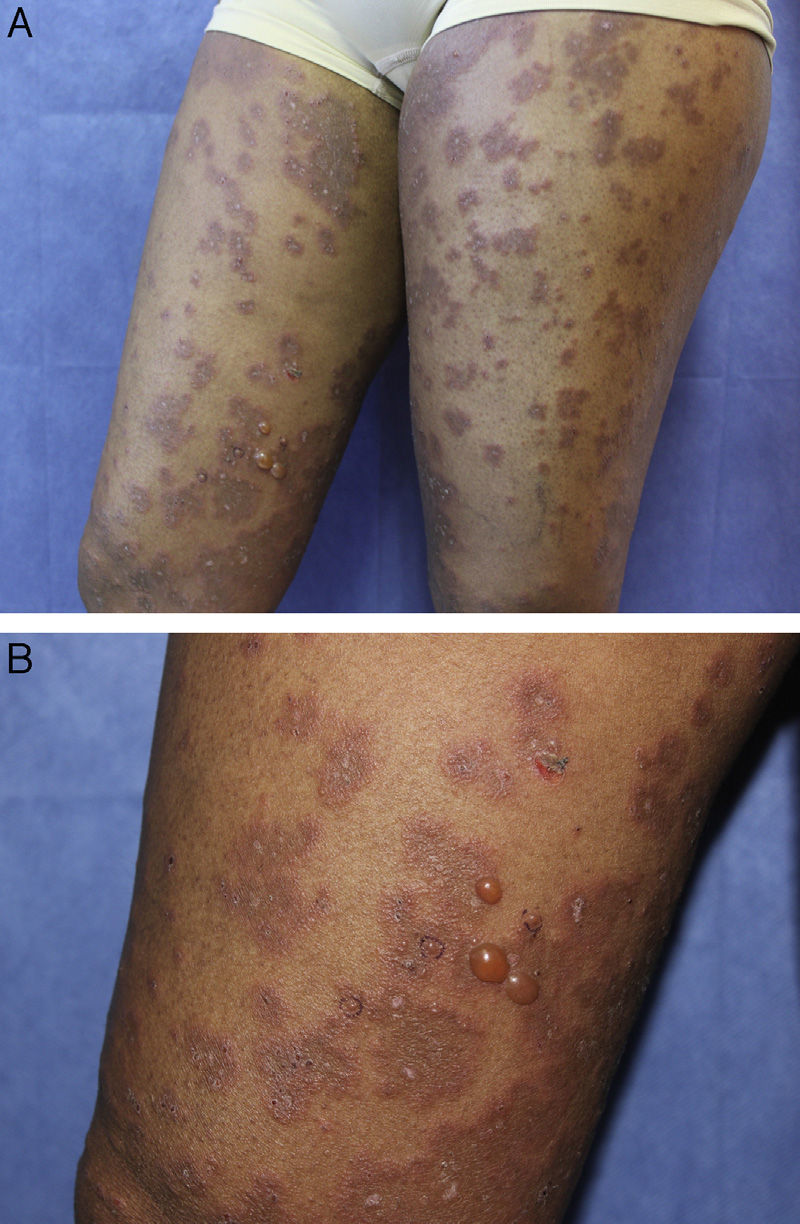

On physical examination, she presented a good general state of health. Examination of the skin revealed multiple well-defined, confluent, edematous erythematous plaques with centrifugal growth, with tense peripheral vesicles and blisters containing a clear fluid, producing a polycyclic, annular morphology (Fig. 1, A and B). The skin lesions affected the face, neck, trunk, and limbs, including the dorsum of the hands and feet. No lesions were observed on the palms, soles, mucosas, nails, or scalp. The Nikolsky and Asboe-Hansen signs were negative.

Laboratory tests including routine biochemistry, urinalysis, coagulation studies, antinuclear antibodies, antitransglutaminase antibodies, serum electrophoresis, and immunoglobulin and complement levels were normal or negative. The only findings of interest were a white cell count of 20000 cells/μL with eosinophilia of 6000 cells/μl, and elevation of the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (35mm in the first hour). Serology for syphilis, hepatitis B and C viruses, and HIV was negative. The Mantoux test was negative. Chest x-ray showed no significant changes of interest.

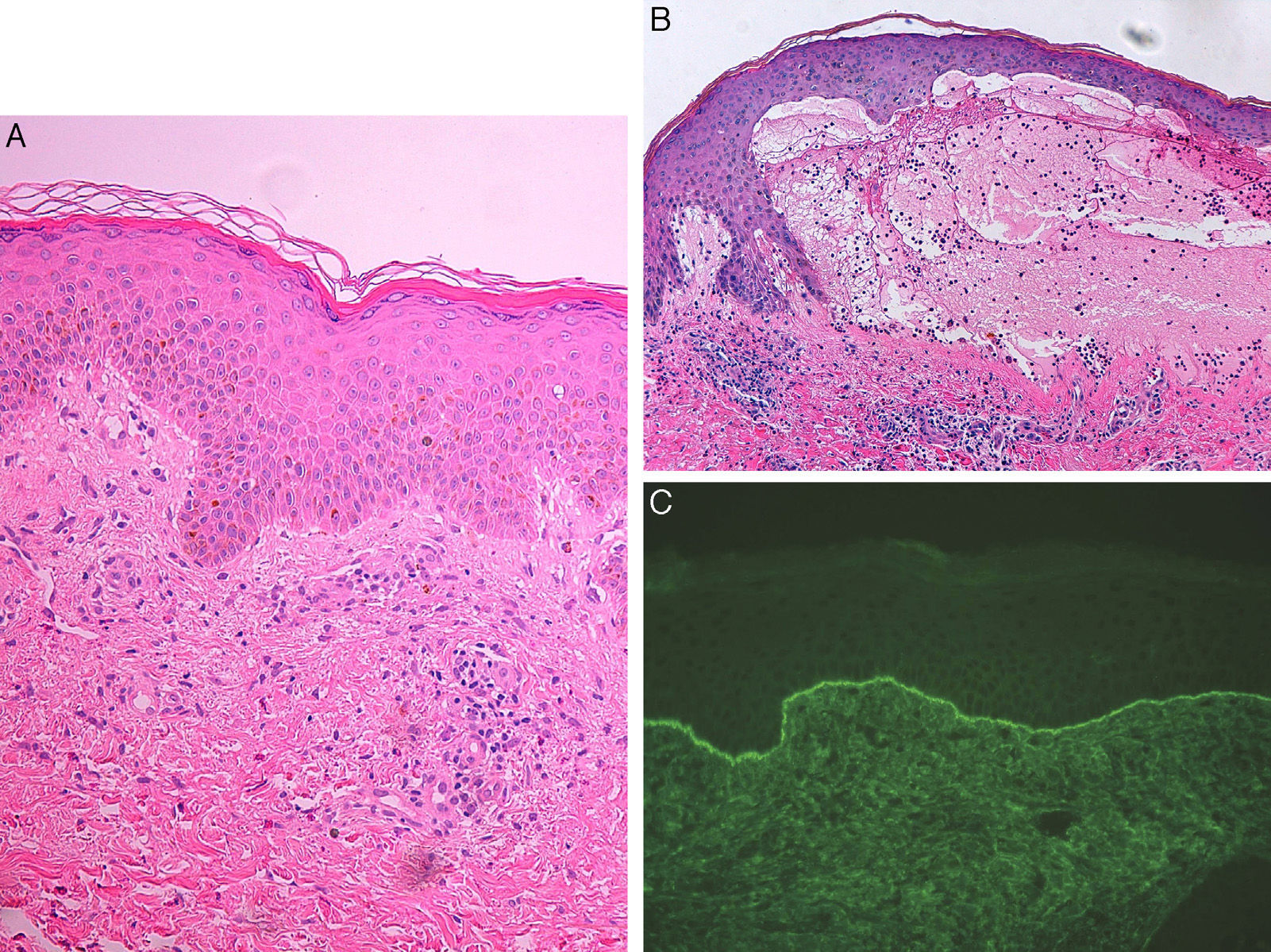

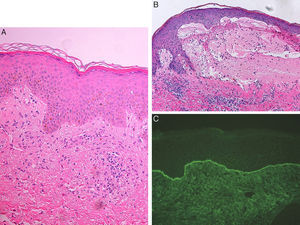

A skin biopsy taken from an urticarial plaque showed a lymphocytic and eosinophilic dermal infiltrate with focal changes at the dermoepidermal interface (Fig. 2A). A biopsy was also taken from a blister, revealing a subepidermal blister associated with a lymphocytic and eosinophilic dermal infiltrate (Fig. 2B). Direct immunofluorescence of healthy perilesional skin was positive, showing linear deposits of IgG and C3 at the dermoepidermal junction with a U-serrated pattern (Fig. 2C). Indirect immunofluorescence on 1M sodium chloride-separated skin showed the presence of circulating antibasement membrane zone antibodies bound on the epidermal side, at a titer of 1:80. Autoimmune studies were positive for circulating antibasement membrane antibodies against antigens BP-180 and BP-230 detected using the immunoblot technique on the patient's serum mixed with human epidermal extracts. Other antibodies studied (Sm, RNP, Ro, La, Scl-70, Jo-1, DNAd, antidesmogleins, collagen VII, antidesmocollins) were negative.

A, Vacuolization of the basal layer of the epidermis with no clear evidence of vesicles or blisters, and the presence of a superficial and deep dermal inflammatory infiltrate with lymphocytes and occasional eosinophils. Hematoxylin and eosin, original magnification×20. B, Subepidermal blister containing fibrin and abundant eosinophils, and a dermal infiltrate of lymphocytes and eosinophils. Marked subepidermal edema is observed close to the blister with early separation of the dermoepidermal junction. Hematoxylin and eosin, original magnification×20.C, Positive direct immunofluorescence with linear deposits of immunoglobulin G and C3 at the dermoepidermal junction.

With a diagnosis of BP, treatment was initiated with oral prednisone, 90mg/d (1.5mg/kg/d), combined with azathioprine, 100mg/d. Two weeks after starting treatment, the patient presented a progressive clinical improvement, and the dose of prednisone was gradually reduced. At the 6-month follow-up, the patient was stable, with no clinical recurrence, and remained on treatment with prednisone, 20mg/d, and azathioprine, 100mg/d; residual postinflammatory hyperpigmentation and milia-like cysts were observed.

The cutaneous manifestations of BP can be atypical and highly polymorphous, and may or may not include the tense blisters characteristic of this entity. A number of atypical presentations have been described1–3: nonbullous, papular, eczematous, nodular, vesicular, annular erythema-like, erythema multiforme-like, erythrodermic, dyshydrosiform, vegetative, lichen planus pemphogoides, infantile, physical agent-induced, drug-induced, and localized (pretibial, vulvar, peristomal, umbilical, postradiotherapy, paralyzed-limb).

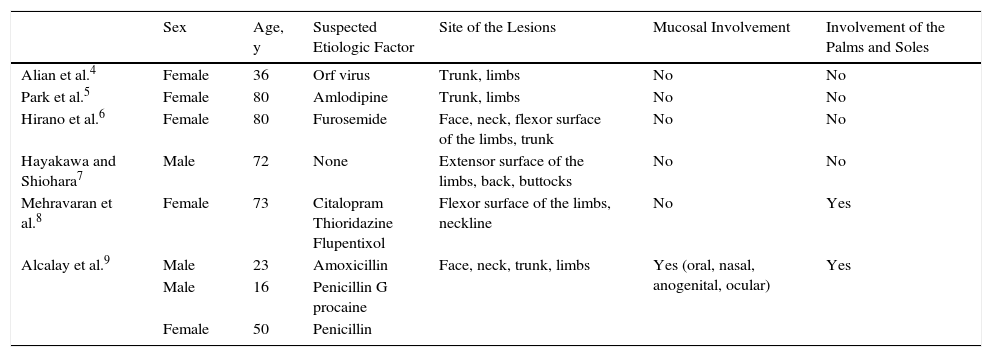

Erythema multiforme-like BP is a rare variant, with only 8 cases reported in the literature (Table 1),4–9 including 5 women and 3 men aged between 16 and 80 years. Suspected triggering factors include orf virus infection, furosemide, citalopram, thioridazine, flupentixol, amoxicillin, and penicillin. Lesions have been most common on the trunk and flexor surfaces of the limbs, although they can arise on any area of skin, including the palms and soles and the mucosas. The clinical findings in all cases included manifestations of erythema multiforme and bullous pemphigoid, and the diagnosis was confirmed by the immunopathology findings.

Description of the Published Cases of Erythema Multiforme-like Bullous Pemphigoid.

| Sex | Age, y | Suspected Etiologic Factor | Site of the Lesions | Mucosal Involvement | Involvement of the Palms and Soles | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alian et al.4 | Female | 36 | Orf virus | Trunk, limbs | No | No |

| Park et al.5 | Female | 80 | Amlodipine | Trunk, limbs | No | No |

| Hirano et al.6 | Female | 80 | Furosemide | Face, neck, flexor surface of the limbs, trunk | No | No |

| Hayakawa and Shiohara7 | Male | 72 | None | Extensor surface of the limbs, back, buttocks | No | No |

| Mehravaran et al.8 | Female | 73 | Citalopram Thioridazine Flupentixol | Flexor surface of the limbs, neckline | No | Yes |

| Alcalay et al.9 | Male | 23 | Amoxicillin | Face, neck, trunk, limbs | Yes (oral, nasal, anogenital, ocular) | Yes |

| Male | 16 | Penicillin G procaine | ||||

| Female | 50 | Penicillin |

Our case was unusual, with early cutaneous manifestations suggestive of erythema multiforme, with centrifugally enlarging erythematous plaques on acral areas and on the extensor surfaces of the limbs, associated with focal histologic changes at the interface and subepidermal edema.

BP must be considered in the differential diagnosis in patients with a diffuse erythema multiforme-like skin rash who develop erythematous or urticarial plaques with peripheral blisters, producing an annular or polycyclic morphology. A high level of clinical and histologic suspicion is required. The diagnosis is confirmed by positive direct and indirect immunofluorescence.1–3

Please cite this article as: Imbernón-Moya A, Aguilar A, Burgos F, Gallego MÁ. Penfigoide ampolloso tipo eritema multiforme. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2016;107:690–692.