Illegal use of Melanotan I and II has been reported and regulatory authorities have issued warnings in the United States and Europe.1,2

Melatonin I and II are synthetic melanocortin analogs (α melanocyte-stimulating hormone) with greater potency and a longer half-life than endogenous α melanocyte-stimulating hormone. Melanotan I (afamelanotide) binds to the melanocortin I receptor (MC1R) to promote melanogenesis, both by proliferation of melanocytes and by regulation of tyrosinase activity. Melanotan II is less selective than its predecessor: it binds to MC2R, causing loss of appetite, and MC3R, initiating penile erections. This triple effect (tanning, loss of appetite, and increased sexual potency) has gained melatonin II the name “Barbie drug” and popularity among some sectors of the population.3 Melanotan II can be administered subcutaneously or as a nasal spray.

Currently in the experimental stage, Melanotan I (afamelanotide) is a promising option in dermatology. Ongoing phase I and II clinical trials are examining the prevention and treatment of erythropoietic protoporphyria, congenital erythropoietic porphyria, solar urticaria, and polymorphous light eruption, as well as the prevention of actinic keratosis and epidermal carcinoma in transplant recipients. The US Food and Drug Administration recently approved a phase II clinical trial of afamelanotide (SCENESSE, Clinuvel Pharmacueticals Ltd) combined with narrowband UV-B therapy for the treatment of vitiligo.4

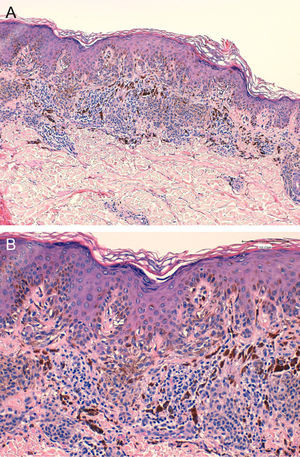

We report the case of a 25-year-old man who came to our department for the sudden eruption of multiple melanocytic nevi and rapid transformation of existing nevi. The changes occurred a few weeks after a 4-week course of subcutaneous Melanotan II. The patient (type II phototype) was a construction worker who regularly used a tanning bed. Examination revealed more than 100 melanocytic nevi, mainly on his back; many were clinically and dermatoscopically atypical (Figs. 1 and 2). We removed the 10 most atypical lesions, some of which were suspected of being melanoma. Histopathology revealed the lesions to be dysplastic melanocytic nevi; in 3 the dysplasia was severe (Fig. 3). A pigmented basal cell carcinoma on the right shoulder was also removed.

Other reports of illegal use of melanocortin analogs have appeared. Langan et al5 reported the first cases of transformation of preexisting nevi in 2 women (aged 30 and 48 years, phototype I/II) after they had used Melanotan I and II. Histopathology revealed benign melanocytic nevi and a severely dysplastic melanocytic nevus. Cardones and Grichnik6 subsequently reported the transformation of existing nevi and eruption of new melanocytic nevi with atypical clinical and histologic characteristics in a 40-year-old patient with a history of dysplastic nevi and melanoma. Cousen et al7 reported the case of a 19-year-old woman who was a regular user of a tanning bed and who developed eruptive nevi after she had used Melanotan II. Ellis et al8 reported a case of melanoma (Breslow depth of 1mm) in a 23-year-old patient who consulted for an increase in size of a pigmented lesion on his leg after use of Melanotan I. The authors could not prove and did not suggest a causal relationship between the use of Melanotan I and development of melanoma. A second case of melanoma associated with this drug was recently reported by Paurobally et al,9 who described the transformation of an existing nevus on the abdomen of a 42-year-old woman 3 months after she had received Melanotan injections; histopathology revealed a 0.3-mm melanoma. Of note, all of these patients had the following risk factors: phototype I or II, multiple melanocytic nevi, personal and family history of melanoma, regular use of tanning beds, and repeated exposure to sunlight. It may be that patients with these factors are more likely to suffer onset and transformation of melanocytic nevi after taking Melanotan, with a potentially increased risk of developing melanoma.

Eruptive melanocytic nevi have been described in the literature in combination with certain bullous dermatoses and compromised immune status (in AIDS, in chemotherapy, and after transplantation).10 In all these cases, determining the potential risk of a new melanoma or transformation to melanoma is both difficult and open to debate. Nevertheless, close dermatoscopic and clinical monitoring is recommended in immunocompromised patients, and the most atypical lesions should be removed.

Easy access to these drugs on the Internet and their growing popularity will probably lead to reports of similar new cases. As dermatologists, we must suspect Melanotan use when faced with transformation of existing melanocytic nevi or the sudden eruption of new ones, especially in individuals with a suntan that is too intense for their skin type or for the time of year. The possibility that body dysmorphic disorder (tanorexia) may also be present should be taken into account in some cases.11

Please cite this article as: Hueso-Gabriel L, et al. Nevos displásicos eruptivos tras el consumo de Melatonan. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2012;103:329-42.