Subcutaneous sarcoidosis accounts for between 1.4% and 6% of skin lesions attributable to sarcoidosis, making it the least common subtype of specific lesion of this disease. It mainly affects white women in the fifth and sixth decades of life.1 The lesions are typically firm, round or fusiform nodules with a diameter of between 0.5 and 2cm; they are mainly found in varying numbers on the upper limbs and are usually bilateral and asymmetric.1 Diagnosis requires histologic evidence of noncaseating granulomas in the subcutaneous tissue, without microorganisms.1

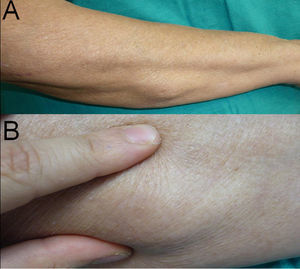

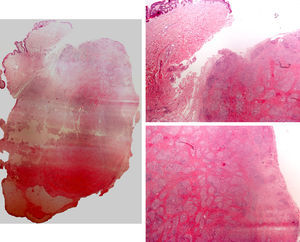

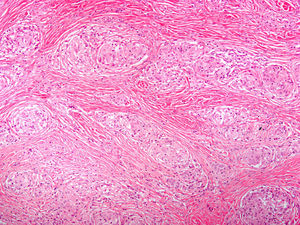

We report the case of a 78-year-old woman with intrinsic asthma diagnosed 3 years earlier who developed subcutaneous sarcoidosis with marked fibroplasia. The patient had consulted for a mass that had appeared on her left forearm a year earlier, a similar mass on her right forearm, which had appeared a month later, and a third mass, which had appeared on her right elbow 3 months before consultation. Both she and her family commented that the size of the lesions had remained stable and that they were slightly tender. The only systemic symptom she reported was occasional joint pain in her upper limbs. Physical examination revealed 2 hard nodules, one on the left forearm and one in the right cubital region, measuring 2.5 and 5cm respectively. They were not fixed to the deeper layers and there were no visible epidermal changes. A third, similar lesion, with a stony-hard consistency and also not adherent to the deeper layers, was observed on the right forearm (Fig. 1, A and B). Biopsy of the nodule on the right elbow showed a central area of sclerotic tissue with numerous sarcoid granulomas visible in the subcutaneous tissue (Figs. 2 and 3). Also visible was a discrete lymphocytic infiltrate. There were no foci of necrosis. An ultrasound scan of the right forearm showed a well-circumscribed, nonencapsulated, oval mass measuring 4.3×1.2cm, with no muscle or bone involvement; the mass was slightly hyperechogenic and contained hypoechoic areas that gave it a mottled appearance. The chest scan showed hilar enlargement, which was confirmed on high-resolution computed tomography, which also revealed a reticulonodular infiltrate in both lungs. Spirometry showed an obstructive pattern, with a forced expiratory volume in the first second to forced vital capacity ratio of 66% of predicted. The electrocardiogram was normal and the Mantoux test was negative. Laboratory tests revealed an elevated creatinine level (2.08mg/dL), an increased calcium to creatinine clearance ratio (0.64; normal range, 0.07-0.17mg/dL), and decreased tubular reabsorption of phosphate (51%; normal range, 79%-89%). Serum levels of vitamin D, parathyroid hormone, calcium, phosphorous, and angiotensin-converting enzyme were within normal limits. No eye alterations were detected. Once the diagnosis of sarcoidosis was confirmed by clinical, histologic, and radiologic findings, the patient was started on prednisone, 30mg once daily, for 6 weeks; the treatment resulted in a considerable improvement in the respiratory symptoms and a reduction in the size of the nodules.

Left, Low-magnification photomicrograph showing normal epidermis and dermis (hematoxylin-eosin, original magnification ×2; images merged using Photomerge). Subcutaneous nodular lesion composed of sarcoid granulomas with perigranulomatous fibroplasia. Right, representative areas of the nodular lesion (hematoxylin-eosin, original magnification ×2).

Clinically, the nodules of subcutaneous sarcoidosis are rather nonspecific, although Pérez-Cejudo et al.2 remarked that they could adopt an elongated form, but without forming cords as occurs in interstitial granulomatous dermatitis with arthritis.2 Nevertheless, because of the nodular nature of the lesions, the differential diagnosis must include conditions associated with substance deposition, cysts, lipomas, calcinosis, rheumatoid nodules, metastases, tuberculosis, cellulitis, and even breast cancer.1

While few studies have analyzed the histologic features of subcutaneous sarcoidosis, it has been suggested that it is a predominantly lobular panniculitis.3,4 It is therefore important to differentiate it from other forms of granulomatous lobular panniculitis such as Q fever.5 Additionally, because of its granulomatous nature, subcutaneous sarcoidosis needs to be differentiated from certain forms of granulomatous septal panniculitis (which are occasionally induced by drugs6,7 or trauma)8 as well as from erythema nodosum. Although this last entity is classified as a predominantly septal panniculitis, when it involves epithelioid granulomas, histology findings can resemble those seen in what has been described by some authors as granulomatous and fibrosing predominantly lobular panniculitis.9 Fibroplasia in subcutaneous sarcoidosis, while not mentioned in most text books, is a characteristic finding and should be expected as it tends to occur extensively in pulmonary sarcoidosis.9 There are several factors that distinguish subcutaneous sarcoidosis from erythema nodosum with epithelioid granulomas, the main differential diagnosis: it is predominantly lobular rather than septal, it has a larger granulomatous than fibroplastic component, the fibroplasia tends to be limited to the perigranulomatous area, there is no evidence of Miescher's radial granulomas, and eosinophils and neutrophils are rarely seen in the inflammatory infiltrate.

It is not yet known whether the extent of fibroplasia is related to the duration of the lesions or to the intensity of the lymphocytic infiltrate,9 but a histologic finding of fibrosing granulomatous panniculitis may be considered to be highly specific for subcutaneous sarcoidosis.10

Please cite this article as: Llamas-Velasco M, et al. Paniculitis sarcoidea fibrosante. Actas Dermosifiliogr.2012;103:331-3.