Injection-site reactions are some of the most common complications in subcutaneously administered treatments.

We report the case of a 31-year-old woman with no known drug allergies, a history of asthma and hidradenitis suppurativa, neither of which was being treated, and relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. For four-and-a-half years, the patient had been receiving treatment with daily subcutaneous injections of 20mg of glatiramer acetate (GA, Copolymer-1, Copaxone, Sanofi-Aventis, Barcelona, Spain).

She visited the emergency department due to acute pain in the left buttock after an injection of glatiramer acetate; the patient had not experienced the pain with previous injections. There was a whitish plaque at the injection site that became erythematous and necrotic over the following 5 days.

Physical examination (Fig. 1) showed a reddish-gray, livedoid plaque on the left buttock, measuring approximately 3cm, with geographic borders, a necrotic center, and a more intensely erythematous-violaceous border. On the caudal part of the lesion there was a deep, round, adherent scab measuring approximately 8mm in diameter.

Questioning of the patient revealed that she complied with the injection protocol: the same injection site was not used in less than a week, the drug was left at room temperature 20minutes before use, and the needle was placed in the correct position. Furthermore, the patient had continued to inject the treatment in the thighs and abdomen in the following days and no lesions had appeared at those sites. She reported a similar event in the same buttock a year earlier that had resolved without treatment and left an area of residual hypopigmentation.

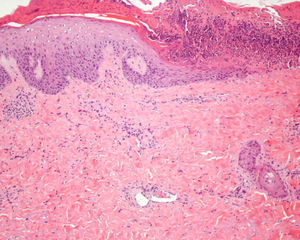

A biopsy was performed of the peripheral area of the skin lesion on the buttock and showed a partially necrotic epidermis with coagulative necrosis of the dermal collagen, fat necrosis, and some fibrin clots in the small blood vessels (Fig. 2). Analyses, including a complete blood count, biochemistry with liver and kidney function tests, immunoglobulins, complement, antibodies to extractable nuclear antigens, antinuclear and anticardiolipin antibodies, and coagulation studies showed no relevant abnormalities.

These data led to a diagnosis of Nicolau syndrome. Topical treatment was instated with fusidic acid and betamethasone twice daily for 10 days; the lesion improved slowly and resolved within a month later, leaving a slightly depressed scar.

Glatiramer acetate is a mixture of synthetic polypeptides that is used to treat relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis and has been shown to reduce the number of relapses of the disease and patient disability.1 The most common adverse event is a reaction at the injection site, producing pain, inflammation, and induration; this occurs in 60% of patients and resolves within hours or days, leaving no residual lesion.2 The rapid resolution of this event differentiates it from panniculitis at the injection site, which is less common, but nonetheless characteristic of glatiramer acetate. This is predominantly lobular panniculitis, which presents clinically as subcutaneous nodular erythematous lesions that resolve in 2 to 3 months and leave residual lipoatrophy in all cases.2

Nicolau syndrome, also known as livedoid vasculopathy or embolia cutis medicamentosa, was first described in 1924 by Freudenthal and then, in 1925, by Nicolau.3 Gay-Prieto4 reported a similar case in 1930. Nicolau syndrome after subcutaneous injection of glatiramer acetate was first reported by Gaudez5 in 2003, and few similar cases have been published since then.6–8 The pathogenic mechanism is not clearly understood, but accidental perivascular or intravascular injection of the drug appears to cause vasospasm and intravascular thrombosis, which gives rise to local skin necrosis due to ischemia.9

This is an unforeseeable but inevitable reaction, in which the injection technique plays a determining role; we also believe that it bears some relation to the drug administered, either due to its molecular weight or to the pH of the excipient used.

Because this reaction is mainly due to the injection technique and not to the drug itself, it should not contraindicate continuation of treatment.

Because the drug is administered daily, when the patient visited our department she had already administered 4 further injections after the appearance of the skin lesion and it was therefore logical to assume that this was not a reaction caused by an immune or allergic mechanism, as in this case the lesion would have recurred in the following days.

Because the patient is right-handed, the left buttock is the most inconvenient and inaccessible site for injecting the drug; the angle of injection or depth of administration of the drug may therefore have been incorrect.

After symptoms resolved and the patient had been advised not to inject in the buttocks, she continued with the same administration regimen and no new lesions had appeared at the injection sites a year after her visit to our department.

Please cite this article as. Martínez-Morán C, et al. Embolia cutis medicamentosa (síndrome de Nicolau) tras inyección de acetado de glatirámero.Actas Dermosifiliogr.2011;102:742-744.