Dermatopathic lymphadenopathy is a well-defined histopathologic entity with an underestimated prevalence in the general population. It is characterized by lymph node enlargement secondary to a typically pruritic skin disorder.1 It is a form of paracortical hyperplasia that usually occurs in chronic skin diseases, but it can also be found in disorders in which the skin is not involved.2 In most cases, dermatopathic lymphadenopathy clinically manifests as enlargement of the peripheral lymph nodes, although normal-sized nodes may also be seen. It should be contemplated alongside malignant, infectious, and other diseases in the differential diagnosis of peripheral lymphadenopathy. It is widely known that a palpable lymph node is a clinical sign and risk marker of a solid or lymphoproliferative tumor,3 and it is therefore essential to establish a diagnosis and monitor patients with this finding. When attending a patient with a chronic skin disorder who presents with enlarged lymph nodes, it is important to consider a broad differential diagnosis that includes autoimmune diseases,4 infections, and tumors.

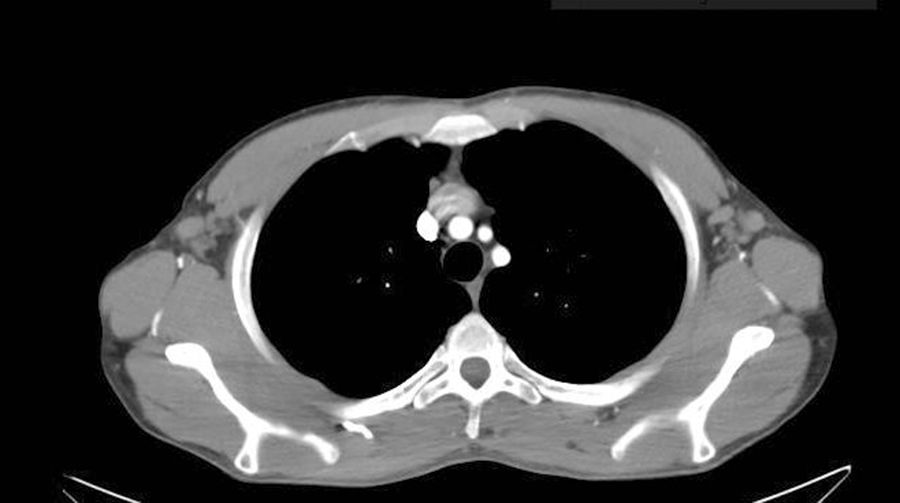

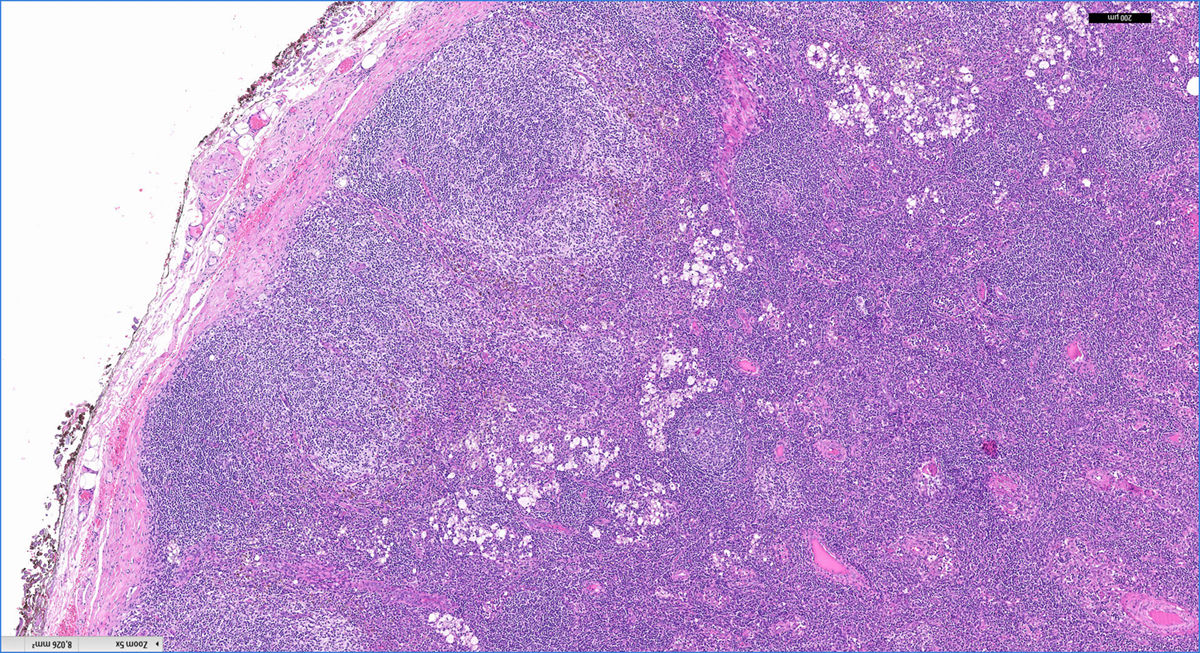

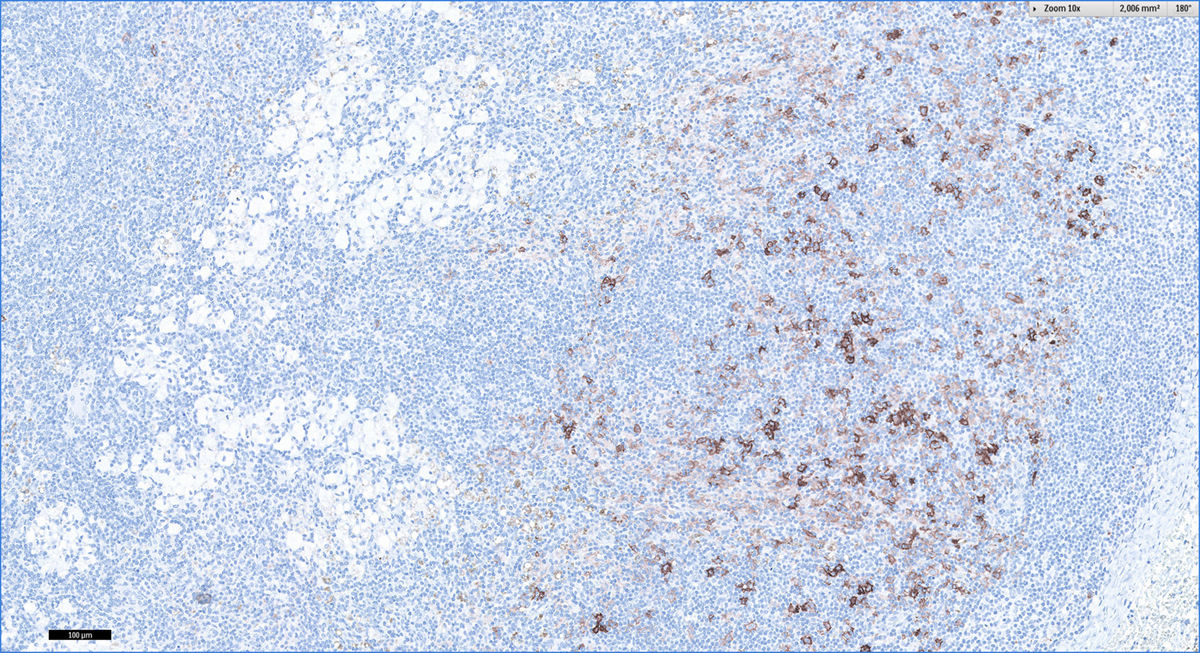

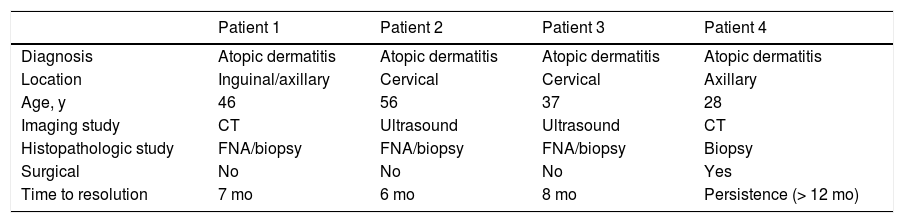

We performed a retrospective analysis of clinically diagnosed and histologically confirmed cases of dermatopathic lymphadenopathy cases at our unit between January 2011 and December 2016. We included 4 patients, whose characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The main diagnosis for which they were under follow-up was atopic dermatitis and there was also an isolated case of lepromatous leprosy. The atopic patients had a Scoring Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD) index score of over 40 at the time of diagnostic confirmation. They also all had active skin lesions. Palpable lymph nodes had been identified in different locations during the physical examination. They were mostly located in the axillary, groin, and neck regions, which were investigated by ultrasound and/or computed tomography (Fig. 1). Depending on their accessibility, the nodes were sampled by biopsy or fine-needle aspiration (FNA) (Figs. 2 and 3). Follow-up duration ranged from 6 months to 5 years. The lymph nodes disappeared in 3 of the 4 patients and reduced considerably in size in the fourth, whose atopic dermatitis is currently being treated with combined oral corticosteroid and intravenous immunoglobulin therapy. None of the patients have presented any signs of malignancy.

Clinical, Imaging, and Histologic Characteristics of 4 Patients With Dermatopathic lymphadenopathy.

| Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | Patient 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis | Atopic dermatitis | Atopic dermatitis | Atopic dermatitis | Atopic dermatitis |

| Location | Inguinal/axillary | Cervical | Cervical | Axillary |

| Age, y | 46 | 56 | 37 | 28 |

| Imaging study | CT | Ultrasound | Ultrasound | CT |

| Histopathologic study | FNA/biopsy | FNA/biopsy | FNA/biopsy | Biopsy |

| Surgical | No | No | No | Yes |

| Time to resolution | 7 mo | 6 mo | 8 mo | Persistence (> 12 mo) |

Abbreviations: CT, computed tomography; FNA, fine-needle aspiration.

Dermatopathic lymphadenopathy is a benign entity with characteristic histologic features that is frequently seen in patients with inflammatory skin disease. It was first described by Pautrier and Woringer in 1937, but the term dermatopathic lymphadenopathy did not appear until 1942, when it was coined by Hurwitt.5 Dermatopathic lymphadenopathy should always be contemplated in patients with persistent lymph node enlargement. It can accompany different types of chronic skin disorders and is more common in patients with extensive skin involvement. Lymph node enlargement tends to be asymptomatic and mainly affects inguinal, axillary, and cervical nodes. The lymph nodes tend to be mobile and not attached to underlying structures.

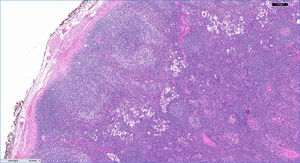

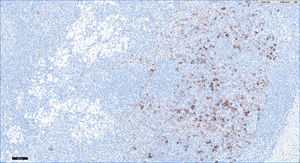

The characteristic histologic findings include slightly expanded germinal centers surrounded by lymphocytes and a widened paracortical area. The follicular pattern is retained. The most characteristic finding is an expanded paracortical area and pale staining due to the presence of Langerhans cells and in particular interdigitating dendritic cells. Macrophages are a minor component, but they are characteristic because they contain cytoplasmic pigment; most of the cells contain melanin but a small proportion contain hemosiderin. Pigment deposits may also be observed in tattoos, nodal nevus cell inclusions, and melanoma metatasases.6

A broad differential diagnosis must be considered in the case of persistent lymph node enlargement. Dermatopathic lymphadenopathy occurs in association with a variety of skin disorders ranging from infections, such as tuberculosis or fungal infections, to erythrodermas, such as psoriatic or atopic erythrodermas (like the cases in our series). Other disorders include sarcoidosis, lymphoproliferative disorders, tumor metastases,7 and infections (e.g., human immunodeficiency virus infection, tuberculosis, and toxoplasmosis). Dermatopathic lymphadenopathy may also been seen in exfoliative or eczematous diseases, such as toxic shock syndrome, pemphigus, neurodermatitis, and atrophia cutis senilis.7 Prognosis is worse when there is associated mycosis fungoides.

The first step in the diagnostic workup is nodal sampling by FNA and/or biopsy. Prior imaging can help identify the extent of disease and select the most appropriate node for biopsy. Considering its increasing use as a diagnostic tool in dermatology, cutaneous ultrasound should also be considered. Inflammatory lymph nodes tend to have an ellipsoid shape with a length to width ratio of over 2, and unlike nodes that are suggestive of tumor infiltration, they tend to have intact corticohilar differentiation. Considering the risk of lymphoproliferative disease, particularly in patients with atopic dermatitis, close follow-up is recommended in the absence of an objective clinical diagnosis. Histologically, dermatopathic lymphadenopathy should be differentiated from Hodgkin lymphoma and enlarged lymph nodes associated with T-cell lymphoma.1

Follow-up is essential. Dermatopathic lymphadenopathy is not only more common in patients with atopic dermatitis, but is also a risk factor for subsequent lymphomas.8

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Bueno-Rodriguez A, Ruiz-Villaverde R, Caba-Molina M, Tercedor-Sánchez J. Linfadenopatía dermopática: ¿realizamos una correcta aproximación diagnóstica? Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2018;109:361–363.