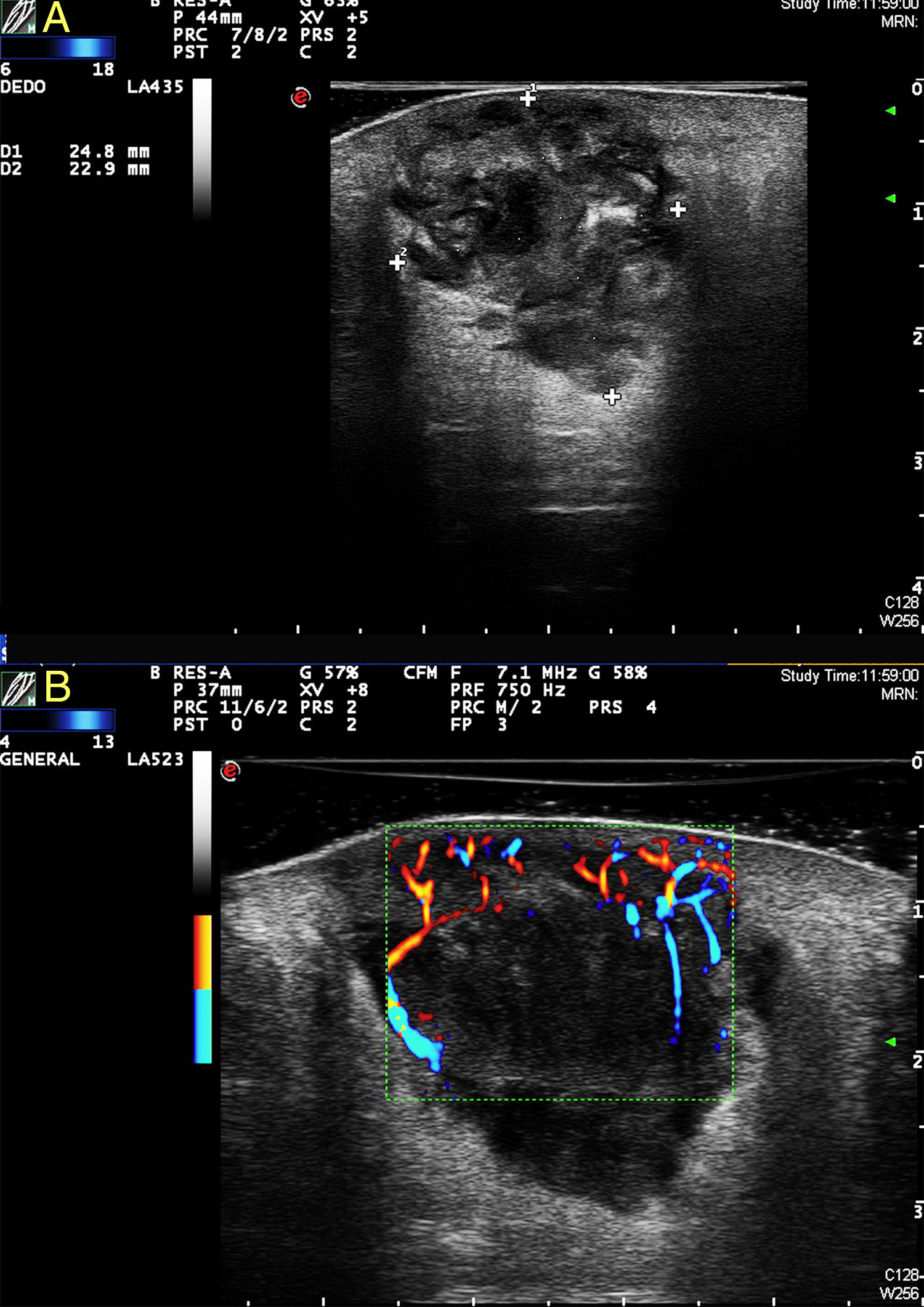

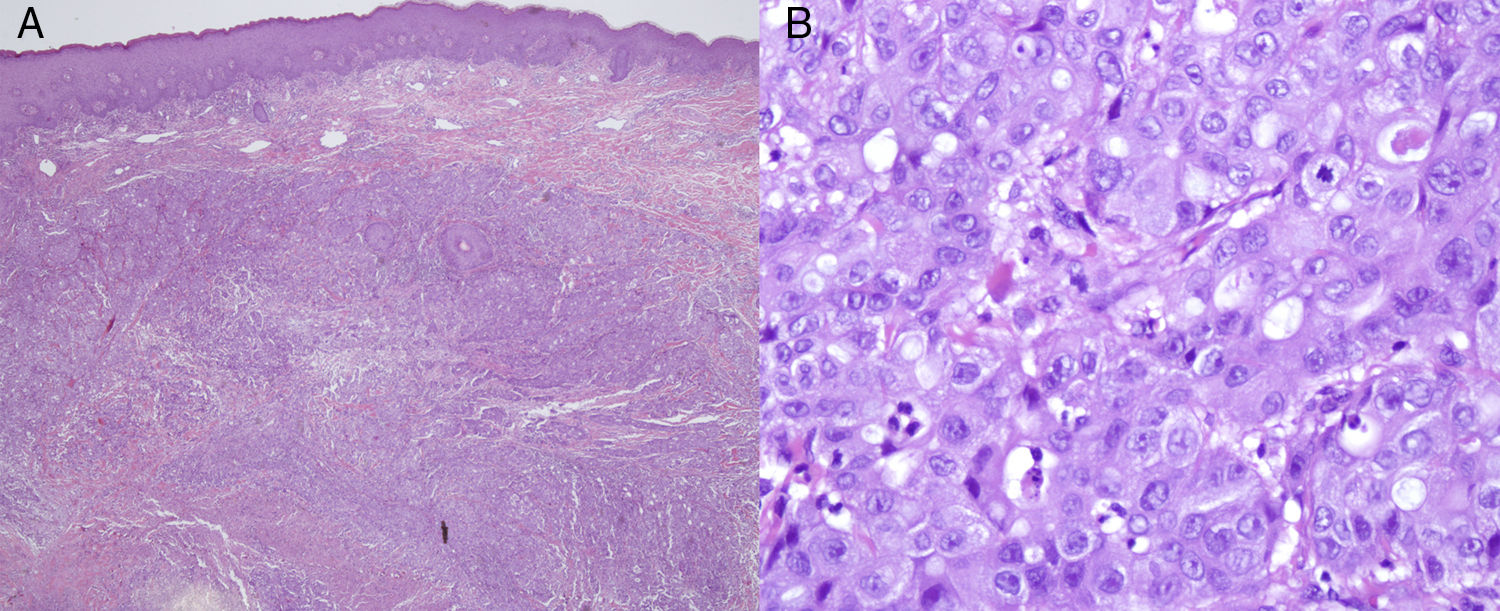

A 55-year-old woman who had smoked since the age of 20 years and had no known diseases or drug allergies was under follow-up at the general surgery department for a painful lesion of 2 months’ duration on the right buttock that had grown despite 2 cycles of oral antibiotics prescribed by her primary care physician. The clinical diagnosis was an infected epidermal cyst and the lesion was drained in the general surgery department. Despite follow-up care over a month, the wound did not heal and the patient was referred to us for evaluation. Physical examination showed an erythematous-violaceous indurated plaque with a 5-cm diameter on the upper outer quadrant of the right buttock (Fig. 1). The plaque, which was hard on palpation, contained an ulcer measuring 15mm at its widest diameter secondary to the surgical drainage. The central area of the ulcer was very deep and its walls contained a solid yellowish-white material. When questioned, the patient reported that she had lost 15kg in 2 months, a loss that she attributed to a naturopathic diet. We examined the lesion by ultrasound and performed a wedge biopsy for histologic and microbiologic studies. The fungal, bacterial, and mycobacterial cultures were all negative. Color Doppler imaging on a MyLabClass C machine (Esaote) equipped with an 18-MHz probe revealed a heterogeneous solid-cystic lesion measuring 45×27mm in the dermis and extending into the subcutaneous tissue. The lesion also had anechoic central areas admixed with hyperechoic areas with well-defined borders (Fig. 2). It displayed posterior reinforcement and Power Doppler imaging showed peripheral vascular poles. The above findings (the heterogeneity and significant vascularity at several poles of the lesion) suggested malignancy, which allowed us to request a rush histology study. Histologic examination showed infiltration of the dermis by a malignant epithelial proliferation of cells with a squamous pattern of growth, marked nuclear pleomorphism, prominent nucleoli, and several mitotic figures; the proliferation formed solid nests with evident intercellular bridges and apoptotic cells (Fig. 3 A and B). There was also extensive necrosis and no signs of connection with the epidermis. The proliferation extended as far as the peripheral and deep borders of the biopsy specimen. With a diagnosis of poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma, we requested a chest radiograph, which showed a nodule in the left lung and a focal interstitial infiltrate containing septal lines and images of nodules in the right lung. Positron emission-tomography-computed tomography confirmed the presence of a disseminated stage IV lung tumor with a large pulmonary mass in the right upper lobe and multiple lung and bone metastases. The study also showed a hypermetabolic soft tissue mass corresponding to the skin lesion on the right buttock. The patient opted to have the lesion completely excised. She was enrolled in a palliative care clinical trial by the oncology department, but died 7 months later.

A, Heterogeneous polylobulated solid-cystic lesion in the dermis and extending into the subcutaneous tissue, coinciding with the histologic image; note the sparing of the superficial area of the dermis. B, Power Doppler imaging showing abundant peripheral vascularity penetrating the lesion from several poles.

Infiltration of the dermis by a proliferation of cells forming solid nests of cells (A) (hematoxylin-eosin, original magnification ×4) with a squamous growth pattern and marked nuclear pleomorphism, prominent nucleoli, and several mitotic figures (B) (hematoxylin-eosin, original magnification ×400).

The skin is a rare site of metastasis from internal malignancies and is estimated to be involved in 0.5% to 9% of all cases.1–4 All types of malignant tumors can produce cutaneous metastasis, but the type most likely to do this varies considerably from one series to the next.3–6

Cutaneous metastases from lung tumors are rare (0%-4% depending on the series) and are associated with a very poor prognosis as the mean survival is just 3 to 5 months.7 Few cases have been reported in the literature.6–8 The clinical presentation of cutaneous metastases is highly variable and includes macules, papules, nodules, and ulcerated lesions. Cutaneous metastases from the lung are typically located on the chest wall, the neck, the abdominal wall, the scalp, or the face.6 Squamous cell carcinoma is the least common histologic subtype of cutaneous metastasis from the lung. Metastasis to the skin is the presenting manifestation of lung cancer in less than 1% of cases, and a high index of clinical suspicion is therefore essential. Many cases are detected late in the course of disease and have no bearing on prognosis. However, in some cases such as ours, their detection permits the diagnosis and treatment of an unknown primary tumor.

High-frequency ultrasound is a fast, affordable, noninvasive technique that can strongly predict malignancy in cases of cutaneous metastasis. Very few articles have been published on ultrasound studies of cutaneous metastases from tumors other than melanoma.3,9,10 Giovagnorio et al.3 found that a polycyclic shape and hypervascularity with multiple peripheral poles were indicative of cutaneous metastasis. The differential diagnosis should include inflamed epidermal cysts, cutaneous lymphomas (which can be accompanied by considerable inflammation), and cystic areas in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. In this last case, sinus tracts and drainage sinuses will be observed both clinically and by ultrasound.

We have presented the case of a young woman with a cutaneous metastasis on the buttock that was the presenting manifestation of a squamous cell lung cancer in which ultrasound examination of the lesion suggested malignancy, allowing us to accelerate the diagnostic process.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Martínez-Morán C, Echeverría-García B, Khedaoui R, Borbujo J. Metástasis cutánea de carcinoma de pulmón. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2018;109:372–374.