Congenital melanocytic nevus syndrome (CMNS) is the result of an abnormal proliferation of melanocytes in the skin and central nervous system caused by progenitor-cell mutations during embryonic development. Mutations in the NRAS gene have been detected in many of these cells. We present 5 cases of giant congenital melanocytic nevus, 3 of them associated with CMNS; NRAS gene mutation was studied in these 3 patients. Until a few years ago, surgery was the treatment of choice, but the results have proved unsatisfactory because aggressive interventions do not improve cosmetic appearance and only minimally reduce the risk of malignant change. In 2013, trametinib was approved for use in advanced melanoma associated with NRAS mutations. This drug, which acts on the intracellular RAS/RAF/MEK/pERK/MAPK cascade, could be useful in pediatric patients with CMNS. A better understanding of this disease will facilitate the development of new strategies.

El síndrome del nevus melanocítico congénito (SNMC) consiste en la proliferación anormal de melanocitos en la piel y el sistema nervioso central, y se debe a mutaciones de las células progenitoras durante el desarrollo embrionario. En muchas de estas células se han detectado mutaciones en el gen NRAS. Se exponen 5 casos de nevus melanocítico congénito gigante, 3 de ellos asociados al SNMC, en los que se ha estudiado dicha mutación. Hasta hace unos años la cirugía era el tratamiento de elección, sin embargo, sus resultados son insatisfactorios, con cirugías agresivas que no mejoran el aspecto estético y reducen mínimamente el riesgo de malignización. En el año 2013 se aprobó el trametinib en el uso del melanoma avanzado con mutaciones de NRAS. Dicho fármaco, que participa en la cascada intracelular de RAS-RAF-MEK-pERK-MAPK, podría ser útil en pacientes pediátricos con SNMC. El conocimiento más amplio de esta enfermedad permitirá crear nuevas estrategias.

Congenital melanocytic nevi are thought to be hamartomas derived from the neural crest. They are the result of postzygotic mutations that lead to defective migration and/or differentiation of melanocytes. These nevi are present at birth or manifest at a very early age.1

In contrast with acquired melanocytic nevus, congenital nevus is usually larger and has a dual cell population. In the first, junctional melanocytes mature and involute in the dermis. In the second, the neuromesenchymal component comprises lymphocyte-like melanocytes that infiltrate more deeply, extending into the lower two-thirds of the dermis and the subcutaneous cellular tissue and potentially infiltrating the cutaneous adnexa and neurovascular structures.2

In 1979, Kopf classified nevi according to size as small (<1.5cm), medium (1.5-20cm), and large (>20cm). When the nevus is greater than 40cm and located on the trunk, it is known as giant (or “garment”) congenital melanocytic nevus.3

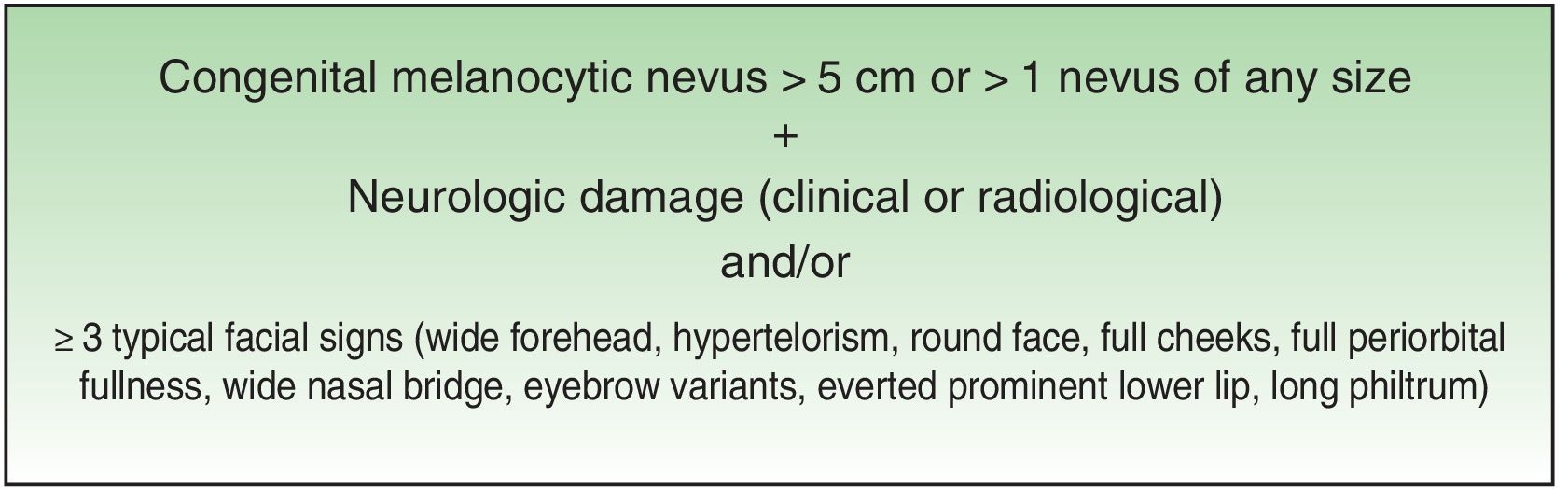

Excessive presence of melanocytic cells on the skin and central nervous system (CNS) was first described by Virchow in 1859 and later referred to as neurocutaneous melanosis by Van Bogaert in 1948. In 1972, Fox proposed the criteria that define this condition, which were revised in 1991 by Kadonga and Friedman.4,5 Today, the condition is known as congenital melanocytic nevus syndrome (CMNS) and is defined as the presence at birth of a melanocytic nevus measuring >5cm or more than 1 nevus of any size associated with neurological damage (clinical or radiological) and/or ≥3 typical facial characteristics6 (Fig. 1).

The risk of developing CNMS in the presence of a giant congenital melanocytic nevus (GCMN) varies according to the series from 2.5% to 45%.7,8 The risk is greater in the presence of multiple congenital melanocytic nevi (previously known as satellite metastases) and, albeit to a lesser extent, with larger nevi.9

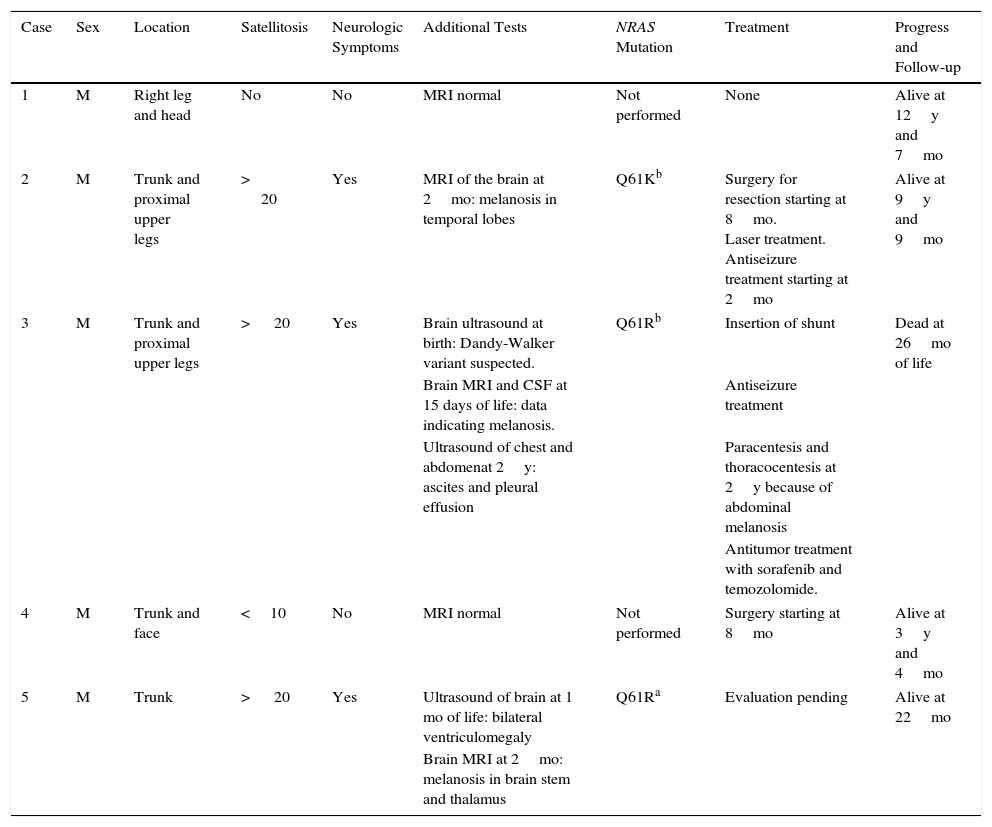

Case SeriesWe present 5 cases of GCMN in patients born in a tertiary hospital between 2003 and 2014 from a total of 47 164 consecutive births, ie, an incidence of 1 case per 9450 liveborn children, which is much higher than that estimated in the literature (1 case per 20 000 liveborn children).3,4 Patients 2, 3, and 5 developed CMNS (Table 1).

Five Cases of Giant Congenital Melanocytic Nevus, 3 of Which Occurred With Neurocutaneous Melanosisa

| Case | Sex | Location | Satellitosis | Neurologic Symptoms | Additional Tests | NRAS Mutation | Treatment | Progress and Follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M | Right leg and head | No | No | MRI normal | Not performed | None | Alive at 12y and 7mo |

| 2 | M | Trunk and proximal upper legs | > 20 | Yes | MRI of the brain at 2mo: melanosis in temporal lobes | Q61Kb | Surgery for resection starting at 8mo. Laser treatment. Antiseizure treatment starting at 2mo | Alive at 9y and 9mo |

| 3 | M | Trunk and proximal upper legs | > 20 | Yes | Brain ultrasound at birth: Dandy-Walker variant suspected. | Q61Rb | Insertion of shunt | Dead at 26mo of life |

| Brain MRI and CSF at 15 days of life: data indicating melanosis. | Antiseizure treatment | |||||||

| Ultrasound of chest and abdomenat 2y: ascites and pleural effusion | Paracentesis and thoracocentesis at 2y because of abdominal melanosis | |||||||

| Antitumor treatment with sorafenib and temozolomide. | ||||||||

| 4 | M | Trunk and face | <10 | No | MRI normal | Not performed | Surgery starting at 8mo | Alive at 3y and 4mo |

| 5 | M | Trunk | > 20 | Yes | Ultrasound of brain at 1 mo of life: bilateral ventriculomegaly | Q61Ra | Evaluation pending | Alive at 22mo |

| Brain MRI at 2mo: melanosis in brain stem and thalamus | ||||||||

Abbreviations: CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

The patient was a newborn girl with GCMN (garment-type) and multiple satellite nevi. At 2 months of age, the patient presented partial seizures, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain revealed hyperintense lesions in T1-weighted images of the temporal lobes. The skin lesions were treated with laser and surgery. The molecular biology study of the skin lesion revealed the presence of the p.Q61K mutation in NRAS. The patient is now 9 years and 7 months old and is progressing favorably (Fig. 2).

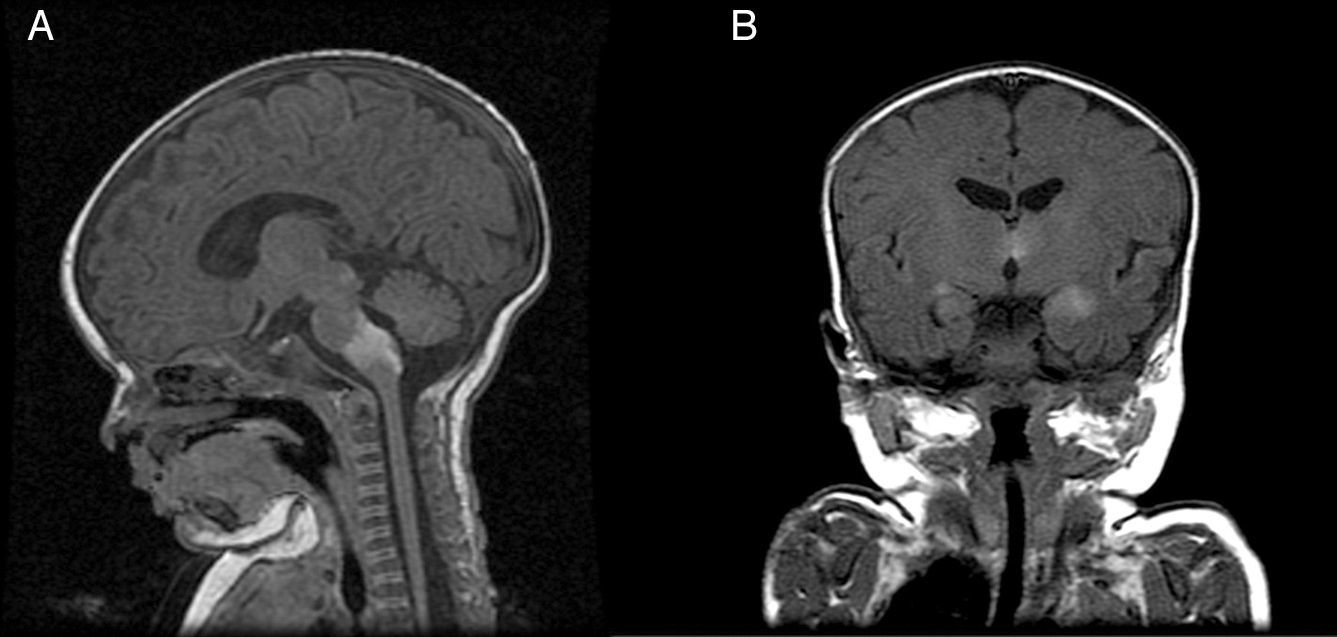

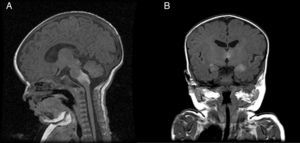

Patient 3The patient was a girl with GCMN (garment-type) and satellite nevi in whom a prenatal ultrasound scan (week 34) revealed an anechoic image in the posterior fossa (Fig. 3). A neonatal ultrasound scan of the head taken at birth revealed ventriculomegaly and cysts associated with the Dandy-Walker variant. A lumbar puncture performed at 15 days after birth revealed the presence of melanocytes, and MRI of the brain revealed the presence of melanosis in the amygdala, thalamus, internal capsule, and brain stem. At 2 months of life, the patient developed intracranial hypertension, and a ventriculoperitoneal shunt was inserted. The patient's condition improved until age 2 years, when she began to experience repeated episodes of pleural effusion and massive ascites secondary to peritoneal melanosis. Therefore, antitumor treatment was started with sorafenib and temozolomide. However, the patient died at 26 months of age. Analysis of the lesion revealed a p.Q61R mutation in NRAS.

Patient 5The patient was a girl with GCMN (garment-type) and satellite nevi. At birth, she presented paralysis affecting the right side and center of her face, sixth nerve palsy, and marked hypertonia. An ultrasound scan of the brain revealed bilateral ventriculomegaly, and MRI of the brain revealed melanosis lesions in the thalami and brain stem (Fig. 4). Analysis of the lesion also revealed the p.Q61R mutation in NRAS. The patient is currently 20 months old and lives in Morocco.

No malignant cutaneous lesions were detected during follow-up.

DiscussionIt has been postulated that CMNS results from sporadic, postzygotic mutations that affect the proliferation and migration of melanocytes between weeks 5 and 21 of gestation.

One of the factors involved is hepatic growth factor, which can bind to the transmembrane c-Met receptor (tyrosine kinase) and activate the RAS-RAF-MEK-pERK-MAPK cascade to stimulate the growth of melanocytes during morphogenesis.

The application of new therapies in patients with the syndrome could be affected by the recently described mutation in codon 61 of the NRAS gene. The mutation appears in the cells of the skin and nerve tissue of patients with CMNS, although it has not been detected in healthy tissue.7,10,11

About 10% of patients with CMNS experience neurological symptoms at some time during their life, generally before the age of 2 years. We can distinguish 2 subgroups, those with intraparenchymal melanosis, who have a better prognosis, and those who develop abnormalities that require surgery, such as hydrocephalus, syringomyelia, or CNS melanomas, all of which have a poorer prognosis.9

Melanin deposits are normal in the leptomeninges, base of the brain, ventral surface of the medulla oblongata at the level of the neck, and the dark matter.12

MRI of the brain is the imaging test of choice for detection of CNS lesions. It is recommended during the first 6 months of life, especially, in the presence of ≥2 congenital melanocytes. The most frequent sites are the amygdala, the cerebellum, the pons, and the spinal cord.5

Recent studies suggest that urine dopamine levels could act as a prognostic marker of disease, since some series report higher values in cases of CMNS than in patients without CNS involvement.13

The finding of a giant nevus at birth requires multidisciplinary management. The risk of developing a melanoma for these patients is not as high as previously thought (2% for GCMN), and it is not known whether surgery reduces this risk, since 30% of malignant lesions do not develop on the base of the nevus.14

To date, symptomatic treatment of congenital melanocytic nevus has been palliative. During the last few years, BRAF inhibitors and MEK inhibitors have been authorized for the treatment of metastatic melanoma. These are efficacious in cases with mutations in NRAS. Mutations in BRAF are common in small congenital melanocytic nevi and in acquired nevi, in which exposure to sunlight plays an important role in malignant transformation. Furthermore, mutations in NRAS have been found in 70%-75% of cases of GCMN and in the nerve tissue of patients who present with CNS involvement. This gene participates in the intracellular NRAS-BRAF-MEK-pERK-MAPK cascade, which, when activated, stimulates the growth of melanocytes.15

A recent article made reference to the compassionate use of a MEK inhibitor in a 13-year-old child with CMNS who died as a result of disease progression. The autopsy revealed diminished expression of pERK in melanocytes.11

MEK inhibitors could potentially be used in selected pediatric patients with GCMN and a mutation in codon 61 in NRAS with the objective of curbing abnormal proliferation of melanocytes. High-quality studies are necessary to demonstrate the safety and efficacy of these drugs for the use referred to above.

New research lines and more in-depth knowledge of embryological aspects and the pathophysiology of this disease will pave the way for new therapeutic applications.

Ethical DisclosuresProtection of humans and animalsThe authors declare that no tests were carried out in humans or animals for the purposes of this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed their institutional protocols on publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no private patient data appear in this article.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Recio Linares A, Sánchez Moya AI, Félix V, Campos Y. Síndrome del nevus melanocítico congénito. Serie de casos Síndrome del nevus melanocítico congénito. Serie de casos. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2017;108:e57–e62.