Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP) is a dermal connective tissue tumor with low malignancy due to its slow growth and locally aggressive nature. It can be classified into several variants according to morphologic features, although there are no major differences in terms of prognosis. The pigmented variant of DFSP, also known as Bednar tumor,1,2 is rare and is characterized by the presence of fibroblasts interlaced with melanin-containing dendritic cells. As with other variants of DFSP, fibrosarcomatous changes may occur; these are characterized by CD34 negativity, scarce melanin pigmentation, and increased cell proliferation and pleomorphism.3,4 This transformation tends to occur in recurrent DFSP and is associated with poor prognosis and an increased risk of metastasis, although the real risk is low.

The identification of the translocation t(17;22)(q22;q13) and the detection of the COL1A1-PDGFB fusion protein in DFSP led to the synthesis of tyrosine kinase inhibitors, such as imatinib as an alternative treatment for unresectable locally advanced disease or metastatic disease5 and sunitinib for nonresponders to imatinib.6

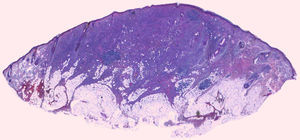

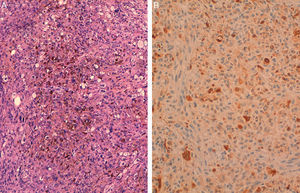

We report the case of a 93-year-old man with a pigmented stain, part of which contained a firm nodular lesion of 1.5cm, located in the left preauricular region (Fig. 1). On observing that the lesion had grown, and based on a clinical suspicion of melanoma on lentigo maligna, the decision was taken to completely excise it. The histopathologic study showed focal atrophy of the epidermis, without ulceration, and a dense proliferation of monomorphic spindle cells with variable pleomorphism throughout the dermis and extending into the subcutaneous tissue (Fig. 2). The spindle cells presented areas with a histiocytic/xanthomatous appearance, abundant melanic pigmentation, and isolated mitotic figures (Fig. 3A). In the immunohistochemical study, the tumor cells showed diffuse positive staining for vimentin, focal staining for CD34 and CD68, and negative staining for pan cytokeratin, actin, desmin, S100 protein, Melan-A, and HMB-45. Positive staining for S100 protein, corresponding to the dendritic cell component, was also observed in dispersed cells (Fig. 3B). Based on the above results, a diagnosis of pigmented DFSP (Bednar tumor) was established.

Pigmented DFSP was described in 1957 by Bednar7 under the name of storiform neurofibroma, but it is currently considered to be a pigmented variant of DFSP with distinctive dendritic cells and melanin pigmentation. Its histogenesis is unclear, and it remains to be elucidated whether it is derived from an undifferentiated mesenchymal cell with the capacity to differentiate itself into a fibroblast or a histiocyte or whether, considering the presence of dendritic cells, it has a neuroectodermal origin. On occasions, onset seems to be associated with local trauma such as burns, vaccine scars, or insect bites.8 The differential diagnosis includes pigmented neurofibroma, cutaneous leiomyosarcoma, spindle cell squamous cell carcinoma, spindle cell melanoma, and atypical fibroxanthoma, among others. Immunohistochemistry and special techniques are essential for differentiating between these entities. The first step is to distinguish between pigmented dendritic cells (which appear brown under typical hematoxylin-eosin staining) and hemosiderin-containing macrophages. Perls stain stains the iron present in blood blue, permitting the identification of hemosiderin secondary to old bleeding. Once hemosiderin-containing macrophages have been ruled out, spindle cell proliferations with dispersed pigmented cells must be investigated by immunohistochemistry. Diffuse expression of vimentin and focal positivity for S100 protein are consistent with pigmented neurofibroma; positive staining for actin and desmin indicate a possible diagnosis of leiomyosarcoma; cytokeratin positivity suggests squamous cell carcinoma; and the expression of S100, Melan-A, and HMB-45 would indicate a possible diagnosis of melanoma. Atypical fibroxanthoma is contemplated when negative results are obtained for the above markers and the other entities in the differential diagnosis have been ruled out, although this tumor typically presents xanthomatous cells with vesicular nuclei and it may express CD10. When Bednar tumor is diagnosed, it is important to remember that these tumors are locally aggressive and invasive and tend to recur locally, but metastasis is rare and delayed. In conclusion, histopathology combined with immunohistochemistry or molecular biology is essential for the correct diagnosis and treatment of Bednar tumor.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Añón-Requena MJ, Pico-Valimaña M, Muñoz-Arias G. Tumor de Bednar (dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans pigmentado). Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2016;107:618–620.