Melanoma remains a prominent health concern. It is one of the most frequent tumors in young adults.1 The incidence and associated mortality has increased in recent decades.2–4

Although metastatic melanoma can only be cured on limited occasions, new immunotherapy treatments5–7 (for example, high-dose IL-2, ipilimumab [anti-cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4], pembrolizumab, and nivolumab [anti-programmed cell death 1], etc.) and combination treatments for specific mutations8,9 (BRAF, mitogen-activated protein kinase [MEK], and c-KIT inhibitors) have increased survival for patients with stage iii and iv disease. At times, melanoma is diagnosed in an advanced phase and a primary tumor is not detected despite exhaustive study. Metastatic melanoma from an unknown primary tumor is defined as the histologically confirmed presence of melanoma in a lymph node, organ, or other tissue without history or evidence of a primary skin, mucosal, or ocular lesion. These metastatic lesions are estimated to comprise 3.2% of all melanomas and they seem to have a better prognosis than those metastatic lesions of known origin.10

We present the cases of 2 patients seen initially in tertiary hospitals with metastatic melanoma of unknown origin who sought a second opinion in our hospital.

Case HistoriesA 67-year-old man was seen in his local hospital with swollen lymph nodes in his left groin. After histologic and immunohistochemical study of one of the swollen lymph nodes, metastatic melanoma of unknown origin was diagnosed. The patient was assessed by an oncologist and a dermatologist, who were unable to locate the primary melanoma. Given that immunotherapy treatment was contraindicated and the BRAF mutation was absent, he received 3 chemotherapy sessions for several months. We are awaiting a reduction in the inguinal mass before palliative lymphadenectomy.

By coincidence, in the same week, we assessed the second patient. He was 45 years old, and had a large and rapidly growing tumor in the left laterocervical region that prompted him to attend his reference hospital. Histologic and immunohistochemical study of the mass pointed to diagnosis of metastatic melanoma. The lesion was positive for the BRAF mutation. In the study of extension by computed tomography-positron emission tomography, lymph node metastases were also found at other sites. After multidisciplinary assessment by an oncologist, a dermatologist, an ear-nose-throat specialist, and a ophthalmologist, he was diagnosed with metastatic melanoma of unknown origin and prescribed treatment with a BRAF inhibitor (vemurafenib) and a MEK inhibitor (trametinib).

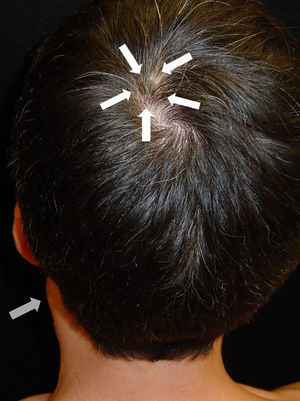

After taking the medical history and the physical examination of the patients, the primary tumor was located in both patients: the first patient had a dark, keratotic pigmented lesion measuring 1.5×1cm, with the Hutchinson sign, on the ball of the left big toe (Fig. 1). The second patient had a hyperpigmented lesion measuring 2×1.5cm in diameter in the left parietal region, with a characteristic atypical dermoscopic pattern (Fig. 2). In both cases, the lesion was evident and was located on a region of the skin that should be examined given the site of the lymph node metastasis. Certain care in the examination was, however, required because the lesion was located on an area of the scalp covered by hair in one case and in the acral most part of the body in the other.

We present 2 cases that may well reflect other avoidable situations in dermatology departments in our hospitals. Although this may appear a diagnostic omission and would have no bearing on the follow-up and therapeutic approach, prognosis does vary according to whether the primary tumor is known or unknown.10

A detailed medical history and careful physical examination are the basis for diagnosis. A study in the United States concluded that the percentage of dermatologists who perform a complete examination of patients with risk factors for melanoma does not exceed 50%.11 Other studies highlight how a complete body examination can assist in early diagnosis of a high percentage of melanomas in patients who attend the clinic for another reason.12–18

In view of the above, the physical examination of the patient in a melanoma unit should be protocolized and meticulous. First, the patient should be examined completely naked, with appropriate light sources, if possible with natural light. The whole body surface should be examined, without omitting the acral areas and those not readily accessible for some patients (retroauricular area, interdigital area, and soles of the feet, etc.). The mucosas (oral, genital, conjunctival, etc.) and appendages (nails and areas with hair follicles) should also be examined. When the patient has been diagnosed with metastatic melanoma of unknown primary tumor, an exhaustive examination of the area of skin drained by the affected lymph node should be undertaken.

Please cite this article as: Ivars M, Redondo P. ¿Exploramos correctamente a los pacientes? ¿Qué nos está pasando?. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2015;106:846–848.