A newborn girl was evaluated in our dermatology department for a congenital tumor in the right frontal region. She is the first child of healthy nonconsanguineous parents and was born following a full-term normal pregnancy and a normal delivery. The mother had no history of infection, drug use, or family history of skin disease.

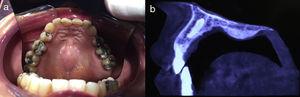

Physical ExaminationThe patient presented an erythematous nodule with a vascular appearance. The nodule was ulcerated, of fibrous consistency, attached to the deeper layers, and measured approximately 3cm in diameter (Fig. 1). No other similar skin lesions or palpable evidence of visceromegaly were observed.

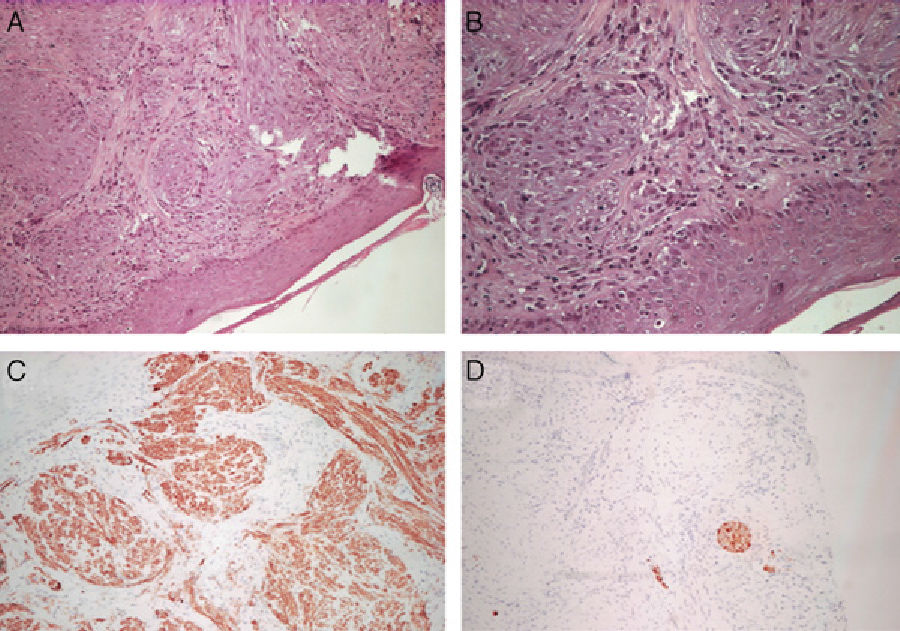

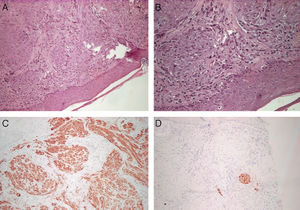

HistologyHistology revealed superficial and deep dermal proliferation of spindle cells with no nuclear atypia. The spindle cells were arranged in cellular bands and fascicles (Fig. 2, A and B). Immunohistochemical techniques showed that the cells were positive for vimentin and smooth muscle α-actin (Fig. 2C) and negative for S100, myoglobin, cytokeratins, and desmin (Fig. 2D).

Additional TestsBone series, abdominal ultrasound, and computed tomography revealed no signs of bone or visceral involvement.

What Is Your Diagnosis?

DiagnosisSolitary infantile myofibromatosis.

Clinical Course and TreatmentA decision was made to adopt a wait-and-see approach and perform periodic examinations. At the time of writing, the tumor continues to regress.

CommentInfantile myofibromatosis (IM) is a congenital mesenchymal disorder characterized by the presence of solitary or multiple myofibroblastic tumors which may affect the skin, soft tissues, bones, or internal organs.1 This disorder was first described by Stout in 1954, although the currently used term was introduced in 1981 by Chung and Enzinger.2 Though considered a rare disease, IM is nonetheless the most common fibrous tumor in infancy. These tumors habitually present between birth and 2 years of age, and lesions limited to the skin tend to have a good prognosis with high rates of spontaneous regression.

Although most cases of IM are sporadic, a familial form has been described in monozygotic twins and in successive generations; it is possible that such cases may be attributable to an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern with variable penetrance.3

The etiology is unknown. Yousefi et al.4 hypothesized that mesenchymal stem cells transferred during pregnancy may participate in tissue remodeling in the fetus, although in a study of tissue samples from 4 newborns with solitary or multiple IM, the authors demonstrated that tumor cells were not derived from maternal chimeric cells. On the other hand, the level of maternal estrogen does appear to influence the development of these tumors, as spontaneous regression occurs after delivery, when the exposure to estrogens has ceased.1,5

There are 3 patterns of clinical presentation: solitary IM (a single lesion affecting the skin and/or muscles in the head, neck, or trunk; this pattern is the most common one in children, representing 75% of all cases); multicentric IM without visceral involvement (multiple lesions limited to the skin and muscles); and multicentric IM with visceral or systemic involvement (multiple lesions not only of the skin and/or muscles, but also of the bones, lungs, heart, and gastrointestinal tract).1

The clinical presentation of cutaneous tumors in IM is heterogeneous: these lesions appear as a plaque, nodule, or mass; are solitary or multiple; measure from 0.5 to 5cm; are not painful; have a firm consistency; rarely ulcerate or bleed; and may have a keloid or vascular appearance.

Biopsy of lesions that are accessible—as is usually the case with skin lesions—is required to confirm the diagnosis. IM skin tumors are well-defined dermal nodules exhibiting a biphasic growth pattern. A high number of spindle cells arranged in fascicles (smooth muscle–like fascicles) can be seen on the periphery of the tumor; these cells show no nuclear abnormalities, although there may be occasional mitotic figures, and they express smooth muscle α-actin and vimentin and are negative for S100. The central area contains vascular structures with irregular lumens and a hemangiopericytic pattern.6

Differential diagnosis in cases of isolated lesions includes deep hemangiomas, neurofibroma, leiomyoma, sarcoma, and neuroblastoma metastasis. From a histologic point of view, a distinction must be made between IM and congenital fibrosarcoma and hemangiopericytoma.3,5

Prognosis for solitary and multiple lesions that do not affect internal organs is excellent, with spontaneous remission occurring in 1 to 2 years, probably related to massive apoptosis.1 A conservative wait-and-see approach is appropriate for these types of IM. On the other hand, IM with visceral involvement is serious and associated mortality is high, especially when gastrointestinal and cardiorespiratory systems are compromised.6 Patients with visceral disease therefore require surgical and/or medical treatment (e.g., radiation therapy or chemotherapy with vincristine, actinomycin D, and cyclophosphamide) in addition to palliative care.

Please cite this article as: Martí-Fajardo N, et al. Tumor congénito ulcerado. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2013;104:525–6.