A 42-year-old woman was referred to our department for the completion of a study on treatment-resistant adult atopic eczema.

The symptoms, which had appeared 5 years earlier, affected the back of both hands and the skin around the mouth and the eyelids. Despite sequential treatment with oral corticosteroids and antihistamines, ciclosporin, and methotrexate combined with systemic corticosteroids, the symptoms worsened.

The patient had been working as a chef for 8 years. She reported partial improvement of lesions during holiday periods and worsening on return to work. She also had oral allergy syndrome symptoms triggered by certain foods.

Physical ExaminationPhysical examination revealed pruritic, lichenified, erythematous-eczematous plaques on the face, the neck, the back of the hands, the forearms, and the cleavage area (Figs. 1 and 2).

Additional TestsTotal immunoglobulin (Ig) E was 11.198 IU/mL and there was elevated specific IgE against latex and various airborne allergens and foods.

Patch tests performed with the standard series of the Spanish Contact Dermatitis and Skin Allergy Research Group (GEIDAC) were all negative.

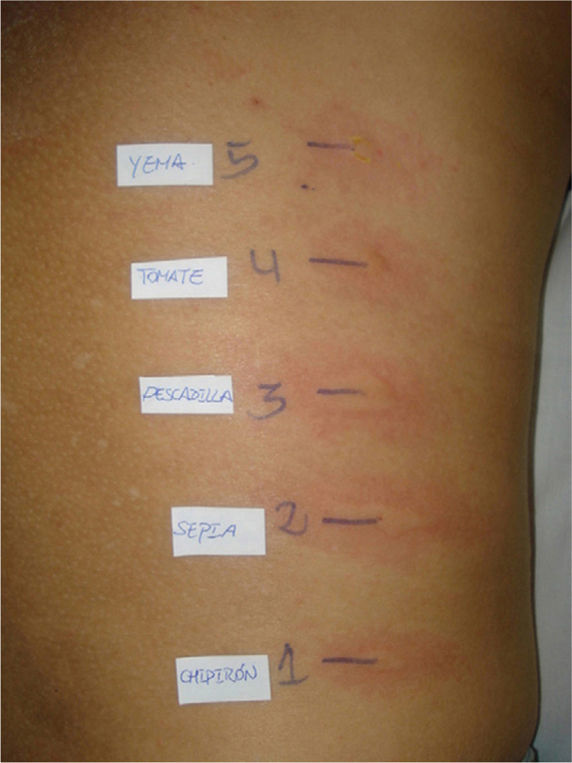

Prick-to-prick tests conducted with food brought in by the patient that she said caused her to itch were positive for baby squid, cuttlefish, whiting, tomato, wheat flour, and egg yolk (Fig. 3).

What is your diagnosis?

DiagnosisProtein contact dermatitis.

Clinical Course and TreatmentThe patient left her job and avoided contact with all foods to which she was sensitized at home. The only treatment administered was tacrolimus ointment 0.1%. At the follow-up visit 8 weeks later, the patient was free of lesions for the first time in 5 years.

CommentProtein contact dermatitis, which was first described in 1976 by Hjorth and Roed-Petersen, is an immediate contact reaction caused by sensitization to high-molecular-weight proteins mostly found in food.

Clinically, it is characterized by pruritus and acute eczematous lesions that appear 10 to 30 minutes after contact with the allergen. If exposure continues, the patient develops typical symptoms of subacute chronic dermatitis, with symptoms worsening with each exposure.

Protein contact dermatitis mainly affects the hands, the forearms, or both. Diffuse eczema of the volar surfaces is the most common clinical manifestation. There have also been reports of localized pulpitis and chronic paronychia.1 Eczema may also affect the face, as occurred in our patient, in the case of airborne allergens or when there is indirect contact via the hands.

Some patients, like ours, may report symptoms of oral allergy syndrome following the ingestion of a food to which they are sensitized, but there have been no reports of digestive allergy symptoms, generalized urticaria, or anaphylaxis.

Protein contact dermatitis is primarily an occupational skin disease, and has been described in chefs, slaughterhouse workers, veterinarians, and food handlers in general; it has, however, also been described in amateur anglers who use worms as bait.2

According to the literature, there is an association between protein contact dermatitis and atopic disease in up to 50% of patients. There have also been reports of an association with pre-existing dermatitis. It seems clear that impaired skin barrier function has an important role in the development of protein contact dermatitis.3

The pathophysiology of the disease remains uncertain. It is an immediate, IgE-mediated contact dermatitis, and in this respect, is similar to immunologic contact urticaria, although the clinical manifestations differ.4

Skin tests are the main diagnostic tool.5,6 The tests of choice are prick-to-prick tests with fresh food, which may be brought in by the patient. Other options are scratch and rub tests, but these only give positive results if performed on affected or previously affected skin; this is one of the characteristics that distinguishes protein contact dermatitis from contact urticaria. Elevated specific IgE levels in serum can also point to a diagnosis of protein contact dermatitis. Patch tests tend to be either negative or irrelevant.

The differential diagnosis should include causes of chronic eczema of the hands—whether of irritant, allergic, or endogenous etiology—and, as occurred in our case, adult atopic dermatitis.

In conclusion, protein contact dermatitis should be suspected in any food handler who develops chronic eczema of the hands, the forearms, or the face. Diagnosis hinges on taking a careful history and performing skin allergy tests. Avoidance of contact with offending allergens can help to achieve complete healing.

Please cite this article as: Esteve-Martínez A, et al. Dermatitis atópica del adulto de evolución tórpida. Actas Dermosifiliogr.2011;102:821-822.