Hailey-Hailey (HH) disease or familial benign chronic pemphigus is a rare bullous skin disorder characterized by recurrent outbreaks of erythematous plaques with a predilection for skin folds1. It is usually misdiagnosed as candidal intertrigo, inverse psoriasis, impetigo, or contact dermatitis1. It is characterized by incomplete suprabasal acantholysis, which gives it the appearance of a ruined brick wall in the epidermis1. HH is due to a mutation of the gene ATP2C1 on the 3q2 1-2 4 chromosome, involving a defect of the ADPase of the calcium in the Golgi apparatus, with deficient calcium-dependent molecular adhesion in the keratinocytes, with subsequent acantholysis2. Medical treatments such as corticosteroids, methotrexate, naltrexone, and dapsone have been used, as have surgical therapies, especially in recalcitrant lesions, such as ablative laser (CO2 and Erbium-YAG), diode laser, pulsed dye laser (PDL), radiofrequency, photodynamic therapy, botulinum toxin, and dermoabrasion1. The utility of the CO2 laser in the treatment of HH, by means of the destruction of the epidermis and the papillary dermis, with significant and persistent improvement, has been reported since 1987. PDL produces photothermal damage, promoting the production of collagen and dermal remodeling, and controlling recurrences by reducing small dermal vessels1. Given this scenario, we propose evaluating the subjective clinical response evaluated by the dermatologist and by the patient, treated with different laser techniques in Hospital Ramón y Cajal, Madrid, Spain. Patients with HH treated with CO2 and/or PDL at our hospital between 2001 and 2019 were enrolled in the study (Table 1). The parameters used were defocused continuous-wave CO2 laser (5-15 W, 2-3 passes) and PDL (10 mm, 0.5 ms, 7 J/cm2). The patients’ clinical records were reviewed to obtain the subjective evaluation of a dermatologist expert in laser technology, and patients were contacted by telephone to obtain their subjective evaluation of the results, with a score from 1 to 5 (where 1 is no response and 5 complete response) for flexibility, exudate, unpleasant smell, and overall evaluation (Table 2). A total of 7 patients were treated (2 women and 5 men), with a mean age of 47 years at the start of treatment (31-67 years), with a family history in 3 out of the 7 cases (43%), and with a satisfactory response evaluated by the dermatologist in 5 out of 6 cases (83%). Evaluation by the patient was obtained in 4 out of 7 cases (57%) and of these, 2 out of 4 (50%) indicated a satisfactory response (Table 2). None of the patients indicated intolerable adverse effects; noted adverse effects were irritation and local erosion, which was adequately controlled with an antibiotic cream for 1-2 weeks with resolution and no associated scarring. To reduce the risk of scarring, we propose defocusing the beam, using short pulses, and reducing permanence time. The optimal treatment point is the vaporization of the superficial dermis, which allows for persistent improvements (between 4 months and 12 years) of over 50% in most patients. The surrounding subclinical area may be treated to prevent recurrences in the periphery3. Although the immediate postoperative phase may be uncomfortable, most patients tend to be very satisfied with CO2 laser therapy4,5. The mechanism of action of this laser in HH is attributed to the fibrosis in the papillary dermis, with the destruction of the mutated keratinocytes and their regeneration from the cutaneous adnexa, such as the eccrine glands, with other keratinocytes with no abnormalities3. Limitations of the use of laser therapy include pain and discomfort, which may persist for between 1 and 4 weeks, although complications do not usually arise if the wound is dressed appropriately3. HH has a major social and occupational impact on patients and in the third case of our series, it limited the patient’s ability to walk. The questionnaires, including effectiveness, pain, cure time, recurrence, new lesions, complications, and general satisfaction, indicate the considerable efficacy of CO2 laser therapy with long-term stability, allowing for substantial improvements in quality of life—very useful improvements due to the high impact on the quality of life of these patients, which can achieve pretreatment scores similar to pemphigus or severe atopic dermatitis4. The limitations of our study include the small number of patients, which did not allow for a correct comparison of the response to both lasers, and the lack of an objective method for evaluating the clinical response. The limitations also include those typically associated with retrospective studies and patients’ memory bias, accentuated by the recurrent presentation of HH. In conclusion, we present a series of 7 patients with HH treated with CO2 laser and/or PDL, with a satisfactory response in 86% and 50% of patients, respectively, evaluated by a dermatologist and by the patients themselves. This discrepancy may be because the disease presents in recurrent outbreaks and because of the time between treatment and contact by telephone. Due to the social and occupational impact of HH, laser therapy is one of the options that should be evaluated in patients who are resistant to other treatments.

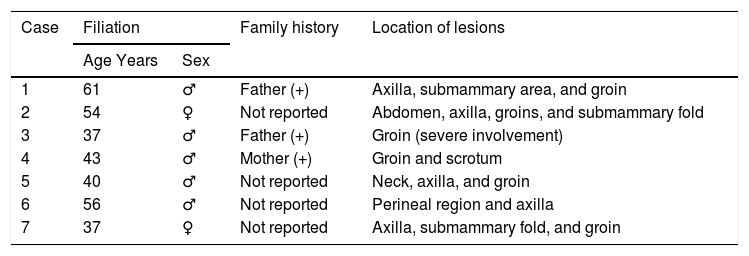

All Patients Recruited. Filiation and Family History.

| Case | Filiation | Family history | Location of lesions | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age Years | Sex | |||

| 1 | 61 | ♂ | Father (+) | Axilla, submammary area, and groin |

| 2 | 54 | ♀ | Not reported | Abdomen, axilla, groins, and submammary fold |

| 3 | 37 | ♂ | Father (+) | Groin (severe involvement) |

| 4 | 43 | ♂ | Mother (+) | Groin and scrotum |

| 5 | 40 | ♂ | Not reported | Neck, axilla, and groin |

| 6 | 56 | ♂ | Not reported | Perineal region and axilla |

| 7 | 37 | ♀ | Not reported | Axilla, submammary fold, and groin |

Abbreviations: + indicates Family member(s) affected;? , response could not be evaluated due to loss of data.

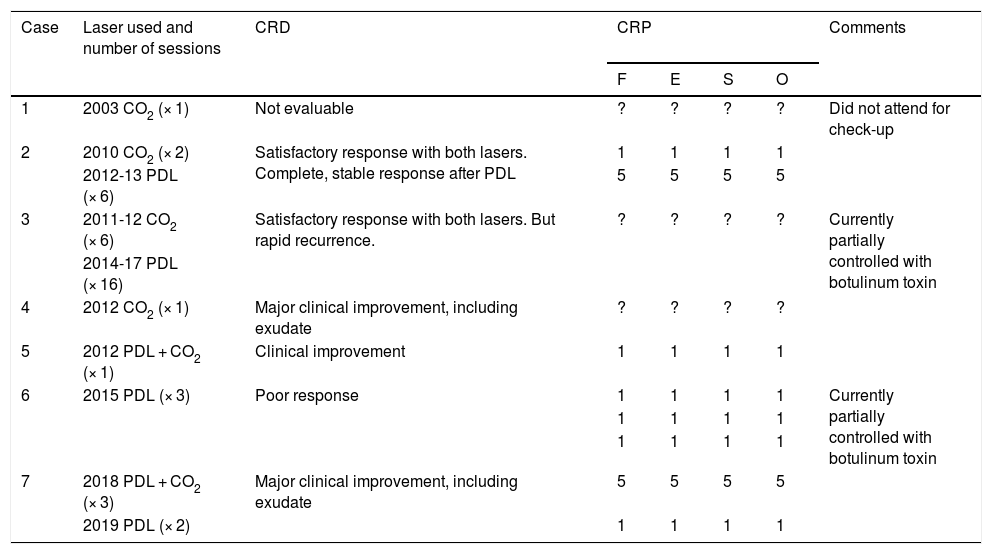

All Patients Recruited and Comparison Between Subjective Clinical Response According to a Dermatologist and According to the Patient.

| Case | Laser used and number of sessions | CRD | CRP | Comments | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | E | S | O | ||||

| 1 | 2003 CO2 (× 1) | Not evaluable | ? | ? | ? | ? | Did not attend for check-up |

| 2 | 2010 CO2 (× 2) | Satisfactory response with both lasers. Complete, stable response after PDL | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| 2012-13 PDL (× 6) | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | |||

| 3 | 2011-12 CO2 (× 6) | Satisfactory response with both lasers. But rapid recurrence. | ? | ? | ? | ? | Currently partially controlled with botulinum toxin |

| 2014-17 PDL (× 16) | |||||||

| 4 | 2012 CO2 (× 1) | Major clinical improvement, including exudate | ? | ? | ? | ? | |

| 5 | 2012 PDL + CO2 (× 1) | Clinical improvement | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| 6 | 2015 PDL (× 3) | Poor response | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Currently partially controlled with botulinum toxin |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 7 | 2018 PDL + CO2 (× 3) | Major clinical improvement, including exudate | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | |

| 2019 PDL (× 2) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

Abbreviations:? indicates Response could not be evaluated due to loss of data; E, exudate; F, flexibility; O, overall evaluation; O, unpleasant odor; CRD, subjective clinical response evaluated by a dermatologist; CRP, subjective clinical response evaluated by the patient.

Please cite this article as: Salas-Marquez C, Boixeda de Miguel JP, del Boz González J. Tratamiento con láser de la enfermedad de Hailey-Hailey en 7 pacientes. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2022;113:207–209.