As dermatologic surgeons often have to perform long surgeries with local anesthetic only, they should be familiar with the fundamentals of how to manage 2 potentially serious complications: Hypertensive crises and intraoperative arrhythmias.

Hypertensive crises can be classified as 1) hypertensive urgencies, characterized by a significant spike in blood pressure (>180/110 mmHg) without target-organ dysfunction or 2) hypertensive emergencies, characterized by a blood pressure above 180/110 mmHg with progressive target-organ damage. In emergencies, the blood pressure needs to be reduced immediately whereas in urgencies the goal is to reduce it over several days. Care must still be taken not to reduce the blood pressure excessively rapidly in emergencies, however, to avoid ischemic injury to vascular beds that have adapted to a high blood pressure.

We recommend that dermatologic surgeons use captopril in hypertensive emergencies because of its safety profile and ease of use. Asymptomatic intraoperative bradycardia does not require treatment, but patients should always be checked to ensure they are alert and responsive. The first step in clinically stable patients with tachycardia is to measure the width of the QRS complex and notify the anesthetist when this is wide.

Dermatologic surgeons should also be familiar with the drugs available in the operating room, ensure that they are easily accessible, and identify the most essential ones so they can familiarize themselves with indications and dosage. Patients should be monitored throughout the operation, and material to secure a peripheral intravenous line should be prepared in case of need. Finally, the dermatologic surgeon should know all the staff working in the operating room and be able to locate the specialist in anesthesia and resuscitation.

Es importante para el cirujano dermatológico, que en muchas ocasiones realiza cirugías prolongadas con el uso exclusivo de anestesia local, conocer el manejo básico de dos complicaciones potencialmente graves: las crisis hipertensivas y las arritmias intraoperatorias.

Respecto a las crisis hipertensivas, diferenciamos entre urgencia hipertensiva: elevación importante de la tensión arterial (>180/110 mm) sin disfunción de órgano diana y emergencia hipertensiva: TA > 180/110 mm Hg con daño progresivo de órgano diana y que requiere de su reducción inmediata. En la primera el objetivo será descender la TA en días y no suele requerir tratamiento urgente, mientras que, en la emergencia hipertensiva, no se recomienda descender la TA excesivamente rápido para evitar daño isquémico en lechos vasculares adaptados a una TA elevada. De elección para el dermatólogo por su perfil de seguridad y sencillez en la emergencia hipertensiva es el captopril. En cuanto a las arritmias: la bradicardia asintomática no precisará de tratamiento, pero siempre comprobaremos que el paciente se encuentra alerta y orientado. En el caso de las taquicardias en las que el paciente esté estable, el siguiente paso sería medir la anchura del complejo QRS y si esté es ancho avisar al anestesista.

Se recomienda conocer los fármacos disponibles en el quirófano, tenerlos en lugar accesible y elegir los imprescindibles para conocer su uso y dosis. Idealmente monitorizar y tener preparado el poder tomar vía periférica en todas las intervenciones en quirófano, así como conocer a todo el personal de quirófano y la localización del especialista en anestesia y reanimación

The incidence of intraoperative hypertensive crises is unknown.1,2 Intraoperative arrhythmias affect up to 70.2% of patients who undergo surgery under general anesthetic, but only 1.6% require treatment. Prevalence with the use of local anesthesia is unknown.2

As dermatologic surgeons often perform long surgeries using local anesthetic alone, they should be familiar with the basic management of 2 potentially severe complications: hypertensive crises and intraoperative arrhythmias.

Hypertensive Crises in the Operating TheaterIntraoperative hypertension will be recognized by monitoring the patient. It may present only as profuse arteriolar bleeding or the patient may complain of cold sweating, headache, or nervousness.1

In the event of higher numbers with repercussions for the target organ, the patient may present neurologic abnormality due to acute cerebrovascular accident, dyspnea due to acute pulmonary edema, or severe chest pain due to acute coronary or aortic syndrome. Acute renal failure is usually asymptomatic.

Given the clinical signs and symptoms described, we can differentiate between the following:

- 1

Hypertensive urgency: significant spike in blood pressure (BP) (most commonly used numbers: BP > 180/110 mmHg) without target-organ dysfunction. This is often a hypertension pseudocrisis due to pain or anxiety.

- 2

Hypertensive emergency: BP > 180/110 mmHg) with progressive target-organ damage, requiring immediate reduction.

The most frequent causes of both types of crisis are anesthetic induction, sympathetic stimulus due to pain or hypothermia, prolonged hypoxia, excess fluid therapy, or suspension of chronic antihypertensive medication (a major and preventable cause that must be taken into account).3–5

How to Prevent ItThe dermatologist must tell patients not to suspend their antihypertensive medication unless expressly ordered to do so by the anesthesiologist, especially in the case of β-blockers, due to the excessive risk of a rebound effect. Treatment with the drugs should also not be instated in the days prior to surgery.

Furthermore, it is potentially helpful for patients to empty their bladder before surgery, as this has been linked to a drop in blood pressure of a mean of 15 mmHg.6

How to Treat ItIn hypertensive emergencies, reducing BP excessively rapidly is not recommended in order to prevent ischemic injury to vascular beds adapted to high pressure. In general, the objective should be to reduce pressure by between 10% and 15% in the first hour and by a further 5%-15% in the following 23 hours (initial goal, <180/120 mmHg and then 160/110 mmHg).5

In hypertensive urgencies, the pressure should be reduced over a matter of days and treatment should begin only if the high blood pressure involves increased surgical morbidity, such as profuse bleeding that prevents surgery from continuing.

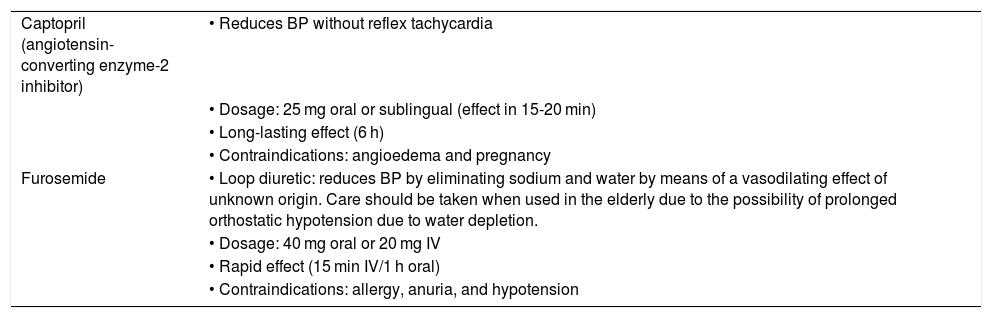

The basic recommended antihypertensive drugs are shown in Table 1. Captopril is the drug of choice for the dermatologist due to its safety profile and simplicity. Nifedipine and amlodipine, calcium-channel blockers that are traditionally used, are the second line of choice in this context due to the risk of coronary or cerebral steal due to sudden peripheral vasodilation and are more commonly used as recue therapy.

Antihypertensive Drugs Most Commonly Used in Hypertensive Crises.

| Captopril (angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 inhibitor) | • Reduces BP without reflex tachycardia |

| • Dosage: 25 mg oral or sublingual (effect in 15-20 min) | |

| • Long-lasting effect (6 h) | |

| • Contraindications: angioedema and pregnancy | |

| Furosemide | • Loop diuretic: reduces BP by eliminating sodium and water by means of a vasodilating effect of unknown origin. Care should be taken when used in the elderly due to the possibility of prolonged orthostatic hypotension due to water depletion. |

| • Dosage: 40 mg oral or 20 mg IV | |

| • Rapid effect (15 min IV/1 h oral) | |

| • Contraindications: allergy, anuria, and hypotension |

Before prescribing an antihypertensive drug, analgesia with paracetamol (1 g IV) or metamizole (2 g IV) should be considered. Intravenous metamizole is preferred due to its hypotensive side effect when administered via this route. Moreover, in patients identified as suffering from anxiety, sublingual administration of 1-2 mg of lorazepam may be considered.

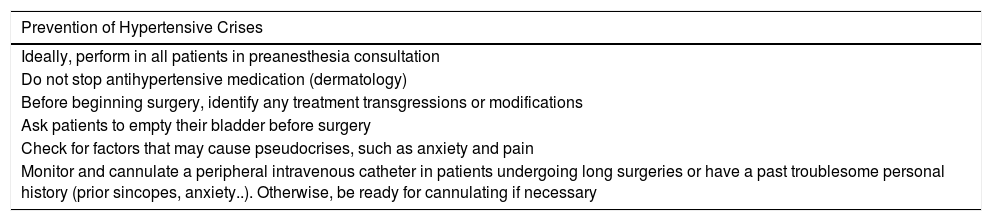

The most important points in terms of prevention and treatment are shown in Table 2.

Prevention and Treatment of Hypertensive Crises.

| Prevention of Hypertensive Crises |

|---|

| Ideally, perform in all patients in preanesthesia consultation |

| Do not stop antihypertensive medication (dermatology) |

| Before beginning surgery, identify any treatment transgressions or modifications |

| Ask patients to empty their bladder before surgery |

| Check for factors that may cause pseudocrises, such as anxiety and pain |

| Monitor and cannulate a peripheral intravenous catheter in patients undergoing long surgeries or have a past troublesome personal history (prior sincopes, anxiety..). Otherwise, be ready for cannulating if necessary |

| Treatment of Hypertensive Crises |

|---|

| Confirm hypertensive crisis (BP > 180/110) with 3 measurements using an appropriate cuff |

| If it is not a hypertensive crisis and there is no intraoperative morbidity, consider not treating |

| Consider treatment with 2 g IV metamizole or 1 mg sublingual lorazepam in patients with pain or anxiety |

| Initial therapy: captopril (25 mg), preferably oral or sublingual after chewing (less desirable, erratic effect and more sudden drop in BP): effect in 15-30 min without reflex tachycardia. Long-lasting effect (6 hours). Dose can be repeated every 15-30 minutes (do not exceed 150 mg). |

| If the patient is resistant to the above measures and requires monitoring → notify anesthesiologist for use of IV drugs → labetalol 10 mg/urapidil 25 mg/furosemide 20 mg |

Monitoring the patient during surgery is essential to recognizing this complication. We must become accustomed to monitoring, especially elderly patients, who are the subjects of most of our interventions. Whenever possible, a 12-lead electrocardiogram must be performed in patients with an abnormal heart rate.

Monitoring is essential in the event of an arrhythmia in order to determine whether the patient is hemodynamically stable (asymptomatic) or unstable (perspiring, with abnormal level of alertness, dyspnea, chest pain, shock).

In the event of signs of instability, the anesthesiologist must be notified immediately, and the team should be prepared for a potential cardiopulmonary resuscitation.3

Asymptomatic bradycardia (heart rate < 60 bpm) does not require treatment, but patients should always be checked to ensure they are alert and responsive.

The first step in clinically stable patients with tachycardia (heart rate > 100 bpm) ist to measure the width of the QRS complex. A QRS measuring 120 ms (3 small squares on the electrocardiogram) or more is considered to be wide.

A normal upright P wave preceding every QRS complex indicates a sinus tachycardia, probably in reaction to the operative setting (anxiety, pain, etc.). This may be managed in the same way as hypertensive pseudocrises (analgesia, anxiolytics, etc.).

If the tachycardia is not a sinus tachycardia, safe action that may help in some narrow-QRS tachycardias involves vagal maneuvers (forced Valsalva maneuver, unilateral carotid massage).7

These actions cause complete atrioventricular block for a few moments, which sometimes returns the patient to a sinus rhythm in some cases of atrioventricular-nodal reentrant tachycardia.7

Wide QRS tachycardias may be considered to be malignant arrhythmias unless proven otherwise, especially if the patient has a history of ischemic heart disease. These tachycardias include ventricular tachycardia and ventricular fibrillation. Thus, the anesthesiologist should be notified to perform an assessment in the case of a wide QRS tachycardia, even if the patient is asymptomatic.

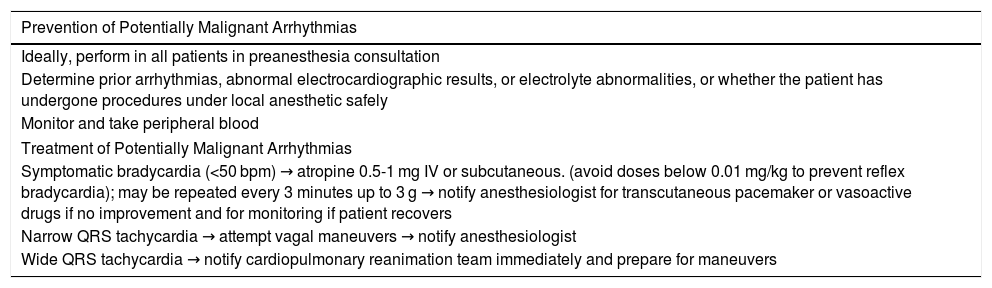

It should be remembered, however, that a wide QRS does not always mean a malignant arrhythmia, as any tachycardia in a patient with a prior bundle branch block will be seen as a wide QRS complex; hence the importance of determining the baseline electrocardiogram of the patient. Prevention and treatment of potentially malignant arrhythmias in the operating theater are shown in Table 3.

Prevention and Treatment of Potentially Malignant Arrhythmias.

| Prevention of Potentially Malignant Arrhythmias |

|---|

| Ideally, perform in all patients in preanesthesia consultation |

| Determine prior arrhythmias, abnormal electrocardiographic results, or electrolyte abnormalities, or whether the patient has undergone procedures under local anesthetic safely |

| Monitor and take peripheral blood |

| Treatment of Potentially Malignant Arrhythmias |

| Symptomatic bradycardia (<50 bpm) → atropine 0.5-1 mg IV or subcutaneous. (avoid doses below 0.01 mg/kg to prevent reflex bradycardia); may be repeated every 3 minutes up to 3 g → notify anesthesiologist for transcutaneous pacemaker or vasoactive drugs if no improvement and for monitoring if patient recovers |

| Narrow QRS tachycardia → attempt vagal maneuvers → notify anesthesiologist |

| Wide QRS tachycardia → notify cardiopulmonary reanimation team immediately and prepare for maneuvers |

As final practical recommendations, the authors advise the following:

- •

Remember dosages and use of just a few drugs (basically captopril and atropine) and keep them at hand.

- •

Ideally, monitor the patient and take peripheral blood in all surgical interventions.

- •

Know the drugs available, theater personnel, and the location of the specialist in anesthesiology and reanimation.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

The authors would like to thank Dr. Emilio del Río and Dr. García Doval for the original idea for this series and Dr. Juan Sánchez Estella for his bibliographic contribution.

Please cite this article as: Rodríguez-Jiménez P, Sampedro-Ruiz R, Imaz I, Chicharro P. Seguridad en procedimientos dermatológicos: crisis hipertensiva y arritmias potencialmente malignas. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2021;112:516–519.