In daily dermatology practice it is not uncommon to encounter psychiatric disturbances that can present as psychodermatoses or as psychological complications of chronic diseases. Delusional parasitosis, psychogenic pruritus, dermatitis artefacta, trichotillomania, and the somatoform disorders belong to the first group, while the archetypal diseases in the second group are psoriasis, atopy, and acne. These patients are usually unwilling to be referred to a psychiatrist and, if referral is achieved, the therapeutic alliance achieved in the clinical interview is lost in many cases. It is therefore necessary for the dermatologist to have a basic understanding of the psychotropic drugs in order to initiate appropriate treatment.1,2

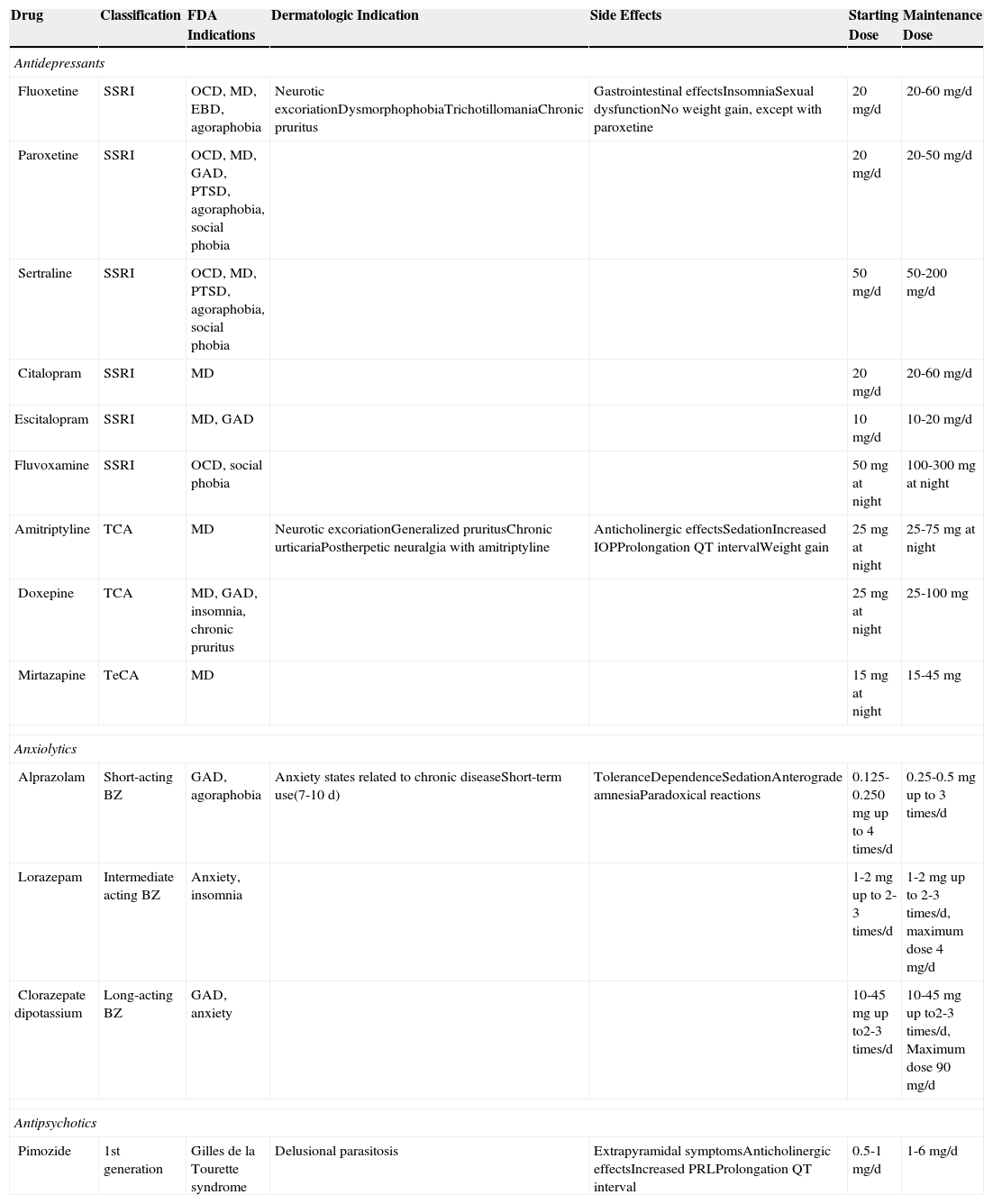

The psychotropic drugs most frequently prescribed in daily clinical practice are the antidepressants, the benzodiazepines, and the antipsychotics (Table 1). Of these 3 groups, the antidepressants—specifically, the serotonin reuptake inhibitors—are the drugs most commonly employed in dermatology consultations. These drugs are safe and have few side effects, the most important of which are gastrointestinal disturbances, insomnia, and sexual dysfunction. They are used particularly in cases of neurotic excoriation, dysmorphophobia, trichotillomania, and chronic pruritus. They must be administered for a minimum of 4 to 6 weeks before the effects become evident, and treatment must be continued for several months. Drug withdrawal must be gradual to avoid recurrence or withdrawal symptoms (anxiety, nausea, diaphoresis, and others).

Main Psychotropic Drugs Used in Dermatology.

| Drug | Classification | FDA Indications | Dermatologic Indication | Side Effects | Starting Dose | Maintenance Dose |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antidepressants | ||||||

| Fluoxetine | SSRI | OCD, MD, EBD, agoraphobia | Neurotic excoriationDysmorphophobiaTrichotillomaniaChronic pruritus | Gastrointestinal effectsInsomniaSexual dysfunctionNo weight gain, except with paroxetine | 20mg/d | 20-60mg/d |

| Paroxetine | SSRI | OCD, MD, GAD, PTSD, agoraphobia, social phobia | 20mg/d | 20-50mg/d | ||

| Sertraline | SSRI | OCD, MD, PTSD, agoraphobia, social phobia | 50mg/d | 50-200mg/d | ||

| Citalopram | SSRI | MD | 20mg/d | 20-60mg/d | ||

| Escitalopram | SSRI | MD, GAD | 10mg/d | 10-20mg/d | ||

| Fluvoxamine | SSRI | OCD, social phobia | 50mg at night | 100-300mg at night | ||

| Amitriptyline | TCA | MD | Neurotic excoriationGeneralized pruritusChronic urticariaPostherpetic neuralgia with amitriptyline | Anticholinergic effectsSedationIncreased IOPProlongation QT intervalWeight gain | 25mg at night | 25-75mg at night |

| Doxepine | TCA | MD, GAD, insomnia, chronic pruritus | 25mg at night | 25-100mg | ||

| Mirtazapine | TeCA | MD | 15mg at night | 15-45mg | ||

| Anxiolytics | ||||||

| Alprazolam | Short-acting BZ | GAD, agoraphobia | Anxiety states related to chronic diseaseShort-term use(7-10 d) | ToleranceDependenceSedationAnterograde amnesiaParadoxical reactions | 0.125-0.250mg up to 4 times/d | 0.25-0.5mg up to 3 times/d |

| Lorazepam | Intermediate acting BZ | Anxiety, insomnia | 1-2mg up to 2-3 times/d | 1-2mg up to 2-3 times/d, maximum dose 4mg/d | ||

| Clorazepate dipotassium | Long-acting BZ | GAD, anxiety | 10-45mg up to2-3 times/d | 10-45mg up to2-3 times/d, Maximum dose 90mg/d | ||

| Antipsychotics | ||||||

| Pimozide | 1st generation | Gilles de la Tourette syndrome | Delusional parasitosis | Extrapyramidal symptomsAnticholinergic effectsIncreased PRLProlongation QT interval | 0.5-1mg/d | 1-6mg/d |

Abbreviations: BZ, benzodiazepine; EBD, eating behavior disorder; FDA, Food and Drug Administration of the United States; GAD, generalized anxiety disorder; IOP, intraocular pressure; MD, major depression; OCD, obsessive-compulsive disorder; PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; TCA, Tricyclic antidepressant; TeCA, Tetracyclic antidepressant.

Other antidepressants used in dermatology are the tricyclic (doxepine and amitriptyline) and the tetracyclic (mirtazapine) antidepressants. Both types block serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine reuptake, whilst also acting as histaminergic, cholinergic, and α-adrenergic receptor antagonists. These drugs are useful in neurotic excoriation, generalized pruritus, and chronic urticaria. Amitriptyline is used in the treatment of postherpetic neuralgia. The main side effects are sedation, blurred vision, dryness of the mouth, urinary retention, constipation, and increased intraocular pressure. Amitriptyline can produce cardiovascular effects, including arrhythmias and prolongation of the QT interval.

The benzodiazepines act mainly as anxiolytics and sedatives and, in dermatology, they are therefore mainly employed to minimize anxiety secondary to a dermatologic disease. They should only be used for short periods as they can induce tolerance and dependence.

The antipsychotics are a group of drugs that are difficult for dermatologists to manage. The most widely used is pimozide, employed as first-line treatment in delusional parasitosis. Remission is achieved in 50% of cases with doses of 2 to 4mg/d.2–4 Pimozide is a dopamine receptor antagonist, and its side effects include extrapyramidal symptoms, blurred vision, orthostatic hypotension, constipation, and urinary retention. It is important to remember that pimozide can stimulate prolactin secretion and prolong the QT interval.

In conclusion, the management of the psychocutaneous disorders requires a multidisciplinary approach in the emerging psychosomatic medicine units. Collaboration between dermatologists, psychologists, and psychiatrists will provide integral treatment for the patient. It is important to perform an adequate psychological evaluation and be prepared to initiate treatment with psychotropic drugs when necessary. The dermatologist should therefore be aware of the main psychotropic drugs.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Rodríguez Martín AM, González Padilla M. FR-Utilización de psicofármacos en dermatología. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2015;106:507–509.