Nevi of special sites (NOSS) are benign melanocytic lesions that occur at particular sites. Although the histological features of NOSS have been described, their immunophenotypic features have not been fully characterized.

AimsTo present the clinicopathological characteristics of a case series of NOSS and to characterize their immunohistochemical profile.

Materials and methodsThirty-five NOSS were assessed using immunoperoxidase staining techniques for the melanocytic (S100, Melan-A, and HMB45) and proliferation (Ki-67) markers.

ResultsAll of the cases of NOSS showed concerning architectural changes (prominent lentiginous melanocytic proliferation, irregularities, crowdedness, and dyhesiveness of the nests), and cytological atypia (large nevomelanocytes with vesicular nuclei, clear cytoplasm, and dusty melanin pigment) that can lead to a misdiagnosis of atypical nevi or even melanomas. All of the cases of NOSS showed diffuse expression of S100 and Melan-A proteins. Ki-67 labeling index of the nevomelanocytes was extremely low. HMB45 protein expression was limited to the junctional and superficial dermal nevomelanocytes.

ConclusionsNOSS can show histological features that can easily mimic atypical nevi or melanomas and this diagnostic consideration should be kept in mind to avoid their misdiagnosis. The expression of HMB45 protein in NOSS indicates that their nevomelanocytic cells have an activated phenotype. The decreased HMB45 protein expression following a gradient from junctional to deeper dermal localization in NOSS is indicative of their immunohistochemical maturation.

Los nevos de localizaciones especiales (“Nevi of special sites”, NOSS) son lesiones melanocíticas benignas que se presentaran en localizaciones particulares. Aunque las características histológicas de los NOSS ya han sido descritas, sus características inmuno- fenotípicas no han sido del todo caracterizadas. Objetivos: Describir las características clínico-patológicas de una serie de casos de NOSS y determinar su perfil inmunohistoquímico.

Materiales y métodosSe evaluaron 35 NOSS utilizando técnicas de tinción con inmunoperoxidasa como marcador melanocítico (S100, Melan-A y HMB45) y de proliferación (Ki-67).

ResultadosTodos los casos de NOSS mostraron cambios arquitectónicos alarmantes (proliferación melanocítica lentiginosa llamativa, irregularidades, conglomerado y cohesión de los nidos) y atipia citológica (melanocitos grandes con núcleos vesiculares, citoplasma claro y presencia de pigmento melánico fino), características que podrían llevar al diagnóstico equivocado de nevo atípico o incluso de melanoma. Todos los casos de NOSS mostraron una expresión difusa de las proteínas S100 y Melan-A. El Ki-67 de los melanocitos névicos fue extremadamente bajo. La expresión de la proteína HMB45 se limitó a los melanocitos junturales y a los dérmicos superficiales.

ConclusionesLos NOSS pueden presentar características histológicas que simularán nevos atípicos o melanomas, por lo que se deben de tomar en cuenta para evitar errores diagnósticos. La expresión de la proteína HMB45 en los NOSS indica que sus melanocitos tienen un fenotipo activado. La disminución de la expresión de la proteína HMB45 en los NOSS, siguiendo un gradiente descendiente desde la zona de la unión hacia la zona dérmica más profunda indica una maduración inmunohistoquímica.

Nevi of special sites (NOSS, also known as nevi with site-related atypia) are growing groups of melanocytic lesions that occur on particular body sites including embryonic milk line (axilla, breast, groin, umbilicus, and perineum), genital, acral, and flexural sites, as well as the head and neck regions. These lesions are not usually accompanied by an increased risk of developing malignant melanomas. They have benign biologic behavior and their complete surgical excision is almost always curative. To date, our knowledge about the biological behavior of NOSS is still rudimentary, and therefore some patients with NOSS may necessitate surveillance following their complete surgical excision.1–5

NOSS can show some concerning histological (architectural and cytological changes) features and sometimes, it is difficult to separate them from other melanocytic neoplasms such as malignant melanomas, atypical nevi, melanocytic nevi with congenital histological features, Spitz nevi, and traumatized melanocytic nevi.4 The alarming architectural changes of NOSS include the lateral extension of the junctional lentiginous nevomelanocytic proliferation (especially noted in the nevi of the scalp and ear), enlargement, crowdedness, and dyhesiveness of the junctional nests, bridging or elongation of the rete ridges (especially seen in the genital and acral nevi).4,6 The atypical cytological features of NOSS include the presence of large nevomelanocytes with enlarged vesicular nuclei, small nucleoli, and pale or powdery cytoplasm with dusty melanin pigment. Other concerning histological features include low-level pagetoid spread and stromal host response in the form of dermal inflammatory cell infiltrate, melanophages and fibroplasia. NOSS can be formed only of a junctional component or have both junctional and dermal components.1–5 The important histological features that help separate NOSS form malignant melanomas include circumscription, symmetry, maturation, lack of significant high-level intraepidermal pagetoid spread, and the lack of significant cytological atypia, necrosis, or mitosis. In NOSS, mutations of several genes including BRAF (genital and conjunctival nevi),7,8 GNAQ, and NRAS (conjunctival nevi), the c-KIT (conjunctival and acral nevi) seem to be involved.

To date, there is limited knowledge about NOSS with only a few studies1–5 that addressed the clinical and morphological features of these lesions. Here, this study presents a case series of NOSS and their detailed clinicopathological and immunohistochemical profiles were addressed.

Materials and methodsIn all, 35 cases of NOSS (acral nevi: 11 cases, flexural nevi: 11 cases, head, and neck nevi: 8 cases, genital nevi: 3 cases, and conjunctival nevi: 2 cases) were identified from the files of this author. The information obtained was analyzed and reported in such a way that the identities of the cases cannot be ascertained. The study did not include any interaction or intervention with human subjects or included any access to identifiable private information. Therefore the study did not require institutional review board. The original hematoxylin- and eosin-stained and immunohistologically stained slides were reviewed in all cases. A panel including immunohistochemical stains (primary antibodies included S100: clone 4C4.9, Melan-A: clone: A103, HMB45: clone HMB45 monoclonal antibodies) and proliferation (Ki-67: clone 30-9 polyclonal antibody) markers were evaluated. The positive (malignant melanoma) and negative (breast tissue) controls were reviewed. Evaluation of the number of HMB45 (activation marker of the melanocytes), Ki-67 (proliferation marker), Melan-A, and S100 positive cells (cytoplasmic staining) was evaluated in 100 cells in 4 high-power fields and reported as the percentage of positive cells following other groups.9 The data were analyzed using IBM SPSS 22 (IBM-SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Mann-Whitney test was performed to compare the percentage of positive cells (S100, Melan-A and HMB45 proteins). All the results were expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean. p values of less than 0.05 were treated as statistically significant.

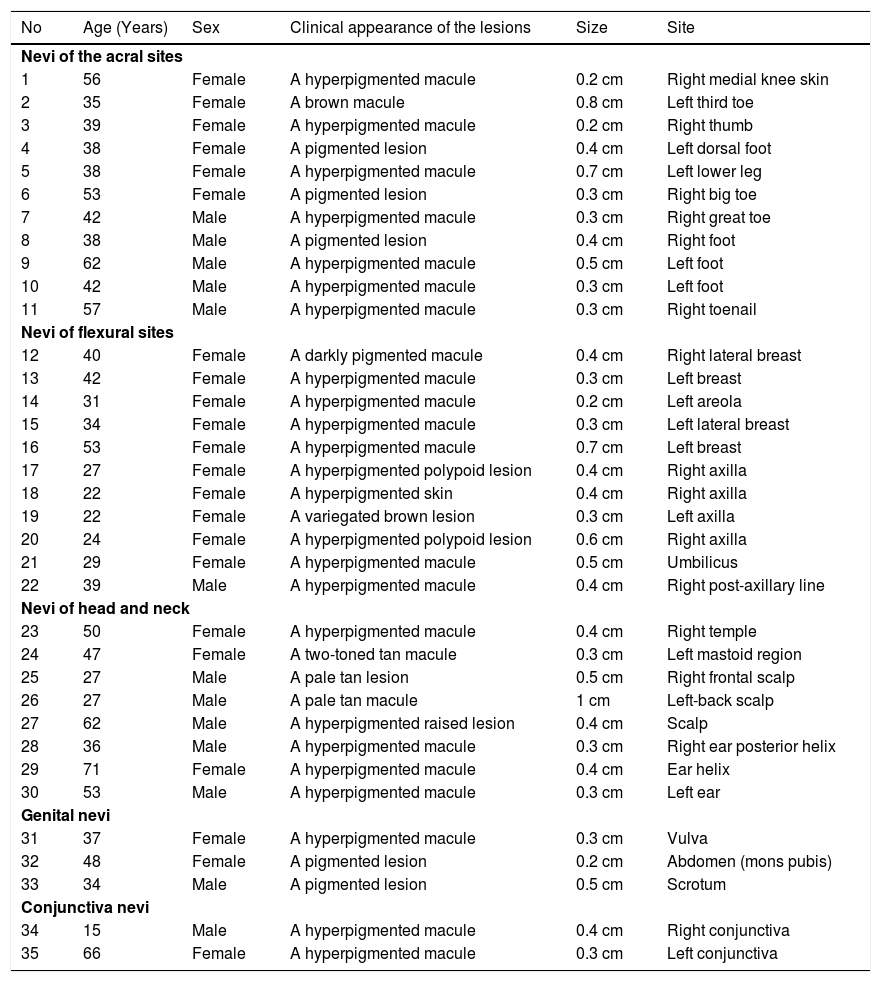

ResultsThe ages of the patients ranged from 15 to 71 years. The mean age of the patients with NOSS was 39.7 ± 2.1. Patients with NOSS in the head and neck region were relatively older. NOSS of the flexural sites were more common in females whereas those of head and neck regions were more common in males. Most NOSS lesions were pigmented, small in size (0.5 ± 0.03 cm), and having the clinical appearance that mimicked atypical nevi. A summary of these findings is shown in Tables 1–2.

Clinical features of the nevi with site-related atypia.

| No | Age (Years) | Sex | Clinical appearance of the lesions | Size | Site |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nevi of the acral sites | |||||

| 1 | 56 | Female | A hyperpigmented macule | 0.2 cm | Right medial knee skin |

| 2 | 35 | Female | A brown macule | 0.8 cm | Left third toe |

| 3 | 39 | Female | A hyperpigmented macule | 0.2 cm | Right thumb |

| 4 | 38 | Female | A pigmented lesion | 0.4 cm | Left dorsal foot |

| 5 | 38 | Female | A hyperpigmented macule | 0.7 cm | Left lower leg |

| 6 | 53 | Female | A pigmented lesion | 0.3 cm | Right big toe |

| 7 | 42 | Male | A hyperpigmented macule | 0.3 cm | Right great toe |

| 8 | 38 | Male | A pigmented lesion | 0.4 cm | Right foot |

| 9 | 62 | Male | A hyperpigmented macule | 0.5 cm | Left foot |

| 10 | 42 | Male | A hyperpigmented macule | 0.3 cm | Left foot |

| 11 | 57 | Male | A hyperpigmented macule | 0.3 cm | Right toenail |

| Nevi of flexural sites | |||||

| 12 | 40 | Female | A darkly pigmented macule | 0.4 cm | Right lateral breast |

| 13 | 42 | Female | A hyperpigmented macule | 0.3 cm | Left breast |

| 14 | 31 | Female | A hyperpigmented macule | 0.2 cm | Left areola |

| 15 | 34 | Female | A hyperpigmented macule | 0.3 cm | Left lateral breast |

| 16 | 53 | Female | A hyperpigmented macule | 0.7 cm | Left breast |

| 17 | 27 | Female | A hyperpigmented polypoid lesion | 0.4 cm | Right axilla |

| 18 | 22 | Female | A hyperpigmented skin | 0.4 cm | Right axilla |

| 19 | 22 | Female | A variegated brown lesion | 0.3 cm | Left axilla |

| 20 | 24 | Female | A hyperpigmented polypoid lesion | 0.6 cm | Right axilla |

| 21 | 29 | Female | A hyperpigmented macule | 0.5 cm | Umbilicus |

| 22 | 39 | Male | A hyperpigmented macule | 0.4 cm | Right post-axillary line |

| Nevi of head and neck | |||||

| 23 | 50 | Female | A hyperpigmented macule | 0.4 cm | Right temple |

| 24 | 47 | Female | A two-toned tan macule | 0.3 cm | Left mastoid region |

| 25 | 27 | Male | A pale tan lesion | 0.5 cm | Right frontal scalp |

| 26 | 27 | Male | A pale tan macule | 1 cm | Left-back scalp |

| 27 | 62 | Male | A hyperpigmented raised lesion | 0.4 cm | Scalp |

| 28 | 36 | Male | A hyperpigmented macule | 0.3 cm | Right ear posterior helix |

| 29 | 71 | Female | A hyperpigmented macule | 0.4 cm | Ear helix |

| 30 | 53 | Male | A hyperpigmented macule | 0.3 cm | Left ear |

| Genital nevi | |||||

| 31 | 37 | Female | A hyperpigmented macule | 0.3 cm | Vulva |

| 32 | 48 | Female | A pigmented lesion | 0.2 cm | Abdomen (mons pubis) |

| 33 | 34 | Male | A pigmented lesion | 0.5 cm | Scrotum |

| Conjunctiva nevi | |||||

| 34 | 15 | Male | A hyperpigmented macule | 0.4 cm | Right conjunctiva |

| 35 | 66 | Female | A hyperpigmented macule | 0.3 cm | Left conjunctiva |

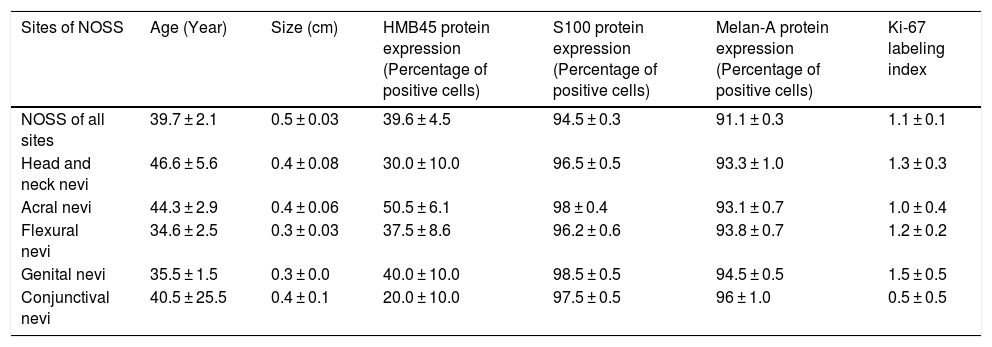

Immunohistological features of the nevi with site-related atypia.

| Sites of NOSS | Age (Year) | Size (cm) | HMB45 protein expression (Percentage of positive cells) | S100 protein expression (Percentage of positive cells) | Melan-A protein expression (Percentage of positive cells) | Ki-67 labeling index |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NOSS of all sites | 39.7 ± 2.1 | 0.5 ± 0.03 | 39.6 ± 4.5 | 94.5 ± 0.3 | 91.1 ± 0.3 | 1.1 ± 0.1 |

| Head and neck nevi | 46.6 ± 5.6 | 0.4 ± 0.08 | 30.0 ± 10.0 | 96.5 ± 0.5 | 93.3 ± 1.0 | 1.3 ± 0.3 |

| Acral nevi | 44.3 ± 2.9 | 0.4 ± 0.06 | 50.5 ± 6.1 | 98 ± 0.4 | 93.1 ± 0.7 | 1.0 ± 0.4 |

| Flexural nevi | 34.6 ± 2.5 | 0.3 ± 0.03 | 37.5 ± 8.6 | 96.2 ± 0.6 | 93.8 ± 0.7 | 1.2 ± 0.2 |

| Genital nevi | 35.5 ± 1.5 | 0.3 ± 0.0 | 40.0 ± 10.0 | 98.5 ± 0.5 | 94.5 ± 0.5 | 1.5 ± 0.5 |

| Conjunctival nevi | 40.5 ± 25.5 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 20.0 ± 10.0 | 97.5 ± 0.5 | 96 ± 1.0 | 0.5 ± 0.5 |

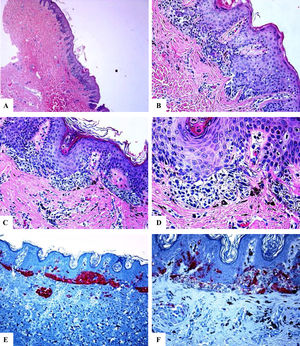

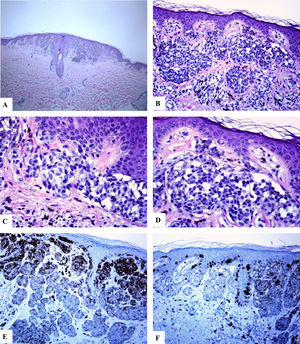

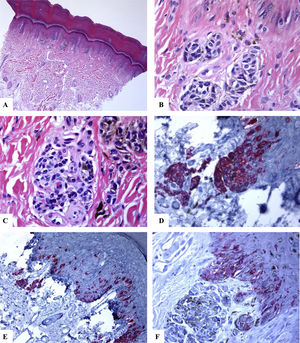

In all of the cases reviewed, there were concerning histological features including the prominence of the junctional lentiginous melanocytic pattern and the presence of occasional benign-looking nevomelanocytes in the middle reaches of the epidermis (acral, and flexural sites), enlargement, crowdedness, dyshesiveness of the junctional and dermal neveomelanocytic nests with variability in their size, shape, and alignments (NOSS at all sites). The nevomelanocytic cells showed mild cytological atypia (nucleomegally, vesicular nuclei, small nucleoli, clear cytoplasm, and fine melanin pigment). Within the dermis, host response in the form of fibroplasia, melanophages and mild lymphocytic infiltrate were seen (genital and acral nevi). Representative cases are shown in Figs. 1–3.

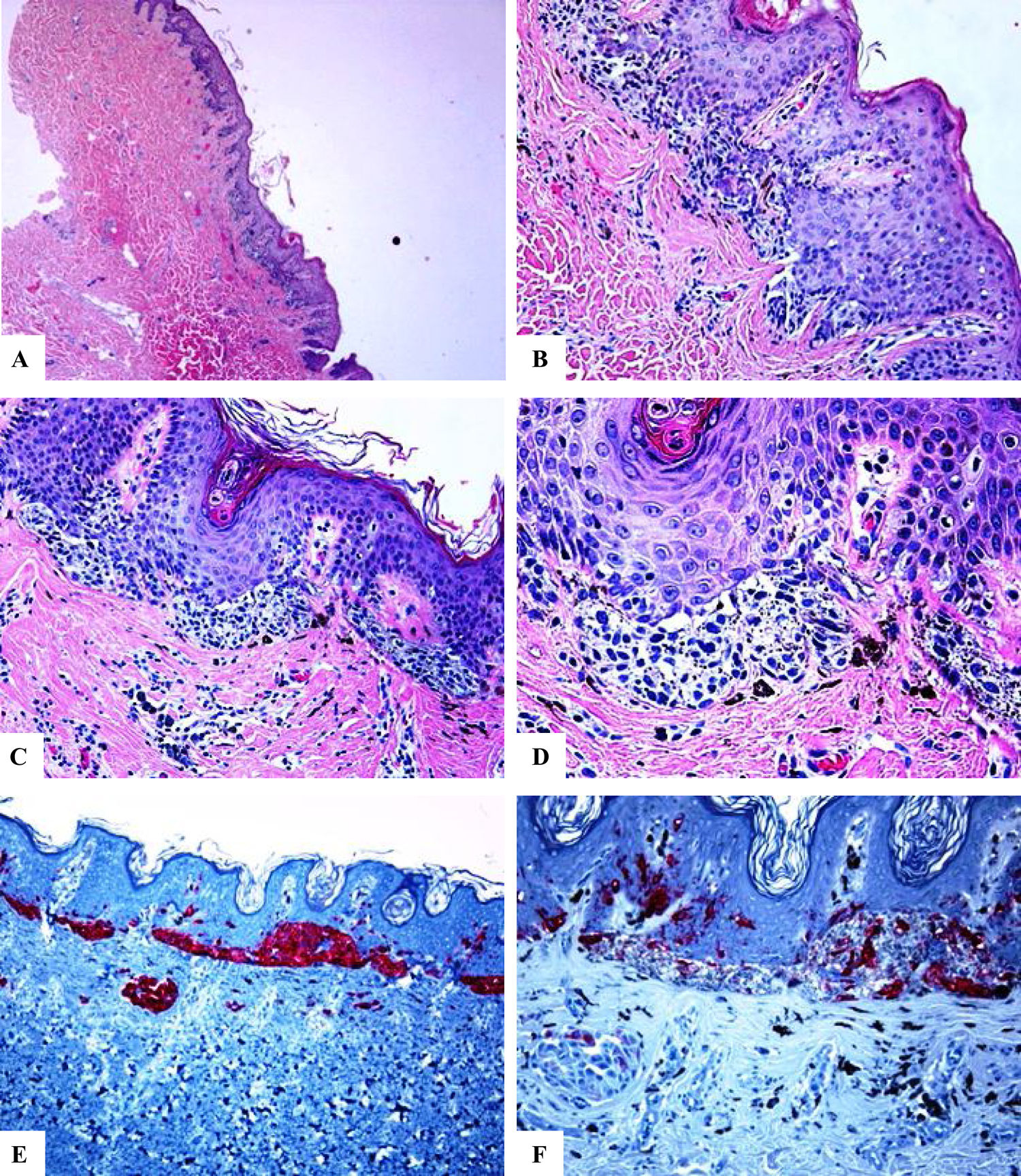

Immunohistological features of melanocytic nevus of the umbilicus with site-related atypia. A-D: A shave biopsy of the umbilical skin shows a small well-circumscribed, symmetric compound melanocytic nevus. The junctional growth shows the lentiginous and horizontally confluent nested pattern. Within the dermis, there are maturing nevomelanocytic nests, fibroplasia, and some melanophages. E: Melan-A strongly and diffusely stains both the junctional and dermal nevomelanocytes. F: A patchy HMB45 staining is seen in the lentiginous, and the nested nevomelanocytes along the dermoepidermal junction. Rare HMB45 positive cells are seen in the dermal nests. HMB45 also stains occasional solitary nevomelanocytes in the epidermis. (Original magnifications: A: 20x, B: x200, C: x200, D: x 400, E: x100, and F: 200).

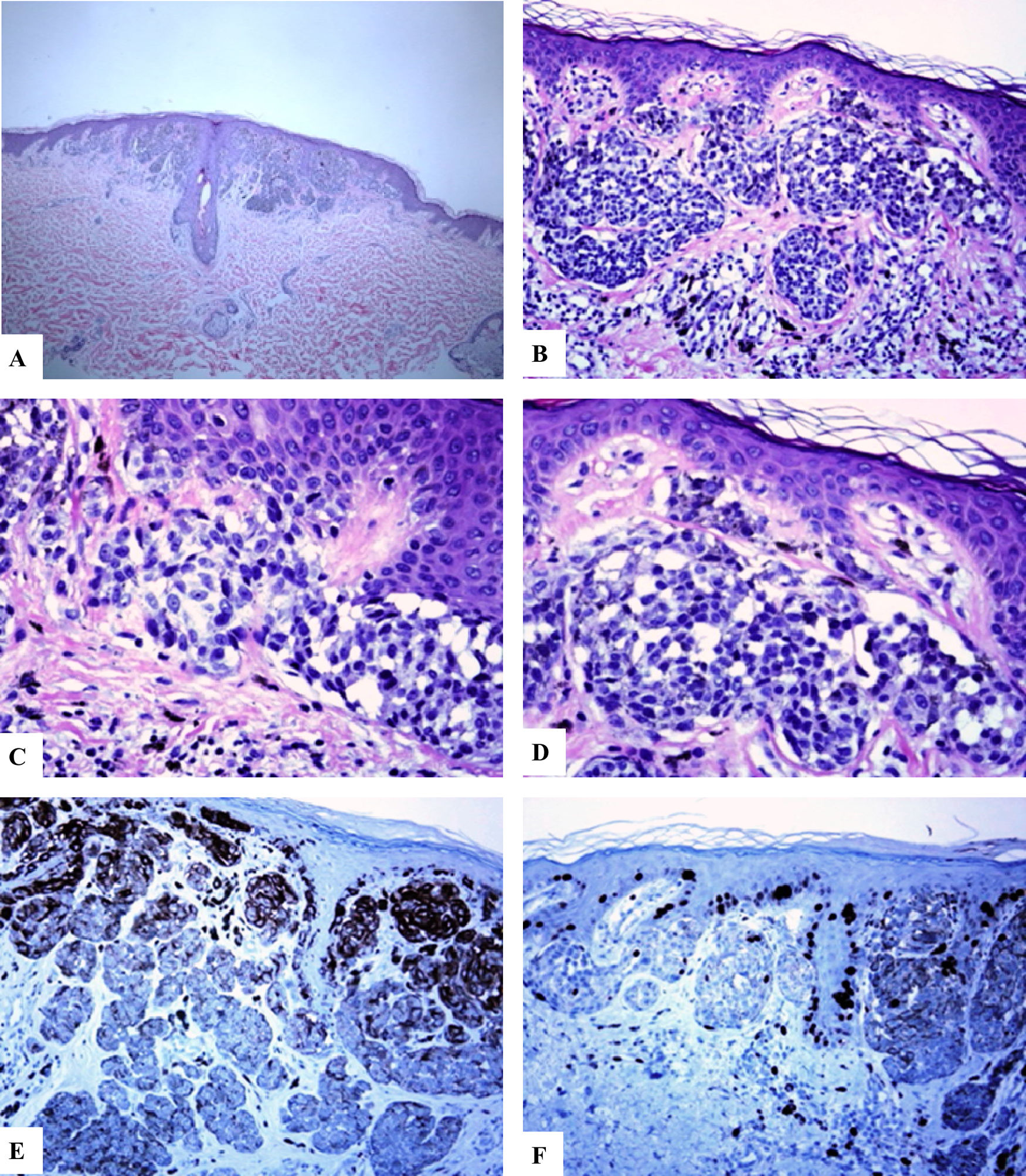

Immunohistological features of melanocytic nevus of the posterior axillary line with site-related atypia: A-D: There is a symmetric compound melanocytic nevus with a predominantly nested pattern and some solitary nevomelanocytes at the dermoepidermal junction. There are horizontally confluent, junctional nests of nevomelanocytes that mature with their descent into the dermis. The nevomelanocytes are dyshesive, enlarged, and have clear cytoplasm with fine melanin pigment. E: A diffuse HMB45 reactivity is seen in the junctional melanocytic growth as well as in nests of the superficial dermis. F: Ki-67 staining is seen both in the junctional keratinocytesand rare nevomelanocytes. (Original magnifications: A: 20x, B: x100, C: x200, D: x 200, E: x200, and F: 200).

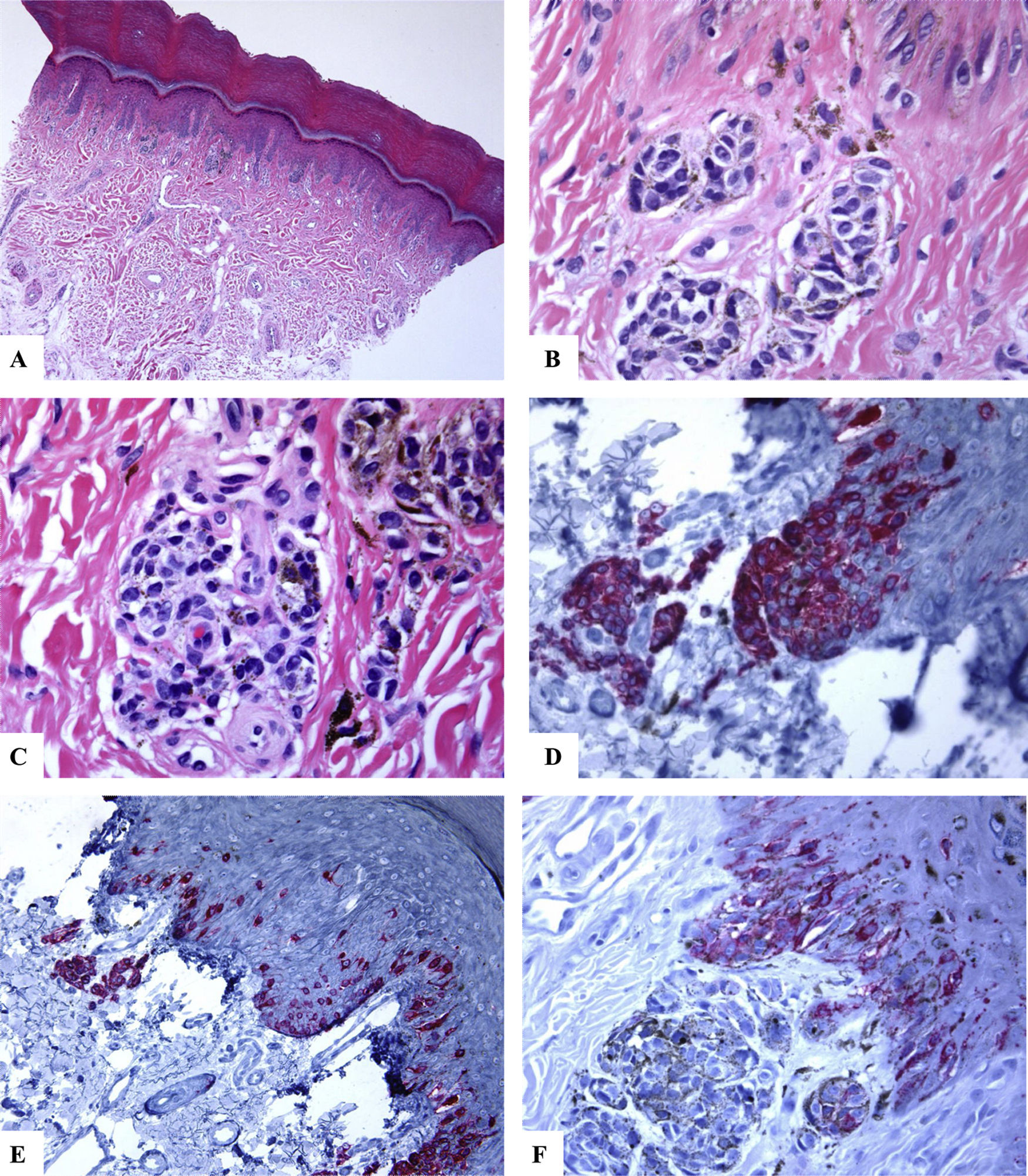

Immunohistological features of acral melanocytic nevus of the right big toe with (Melanocytic Acral Nevi with Intraepithelial Ascent of Cells, MANIAC): A-C: Sections show acral skin with a small well-circumscribed, symmetric compound melanocytic nevus. There is no confluence of nests. The nevomelanocytes lack any significant cytological atypia. Within the dermis, there are fibroplasia and few melanophages. D-E: Melan-A decorates the junctional and dermal nevomelanocytes. It shows a lentiginous pattern with the upward pagetoid migration of some nevomelanocytes (lacking cytological atypia) arranged as solitary units in the spinous layer (MANIAC). F: A patchy HMB45 staining is seen in the lentiginous nevomelanocytes along the dermoepidermal junction. HMB45 also stains occasional solitary nevomelanocytes in the lower reaches of the epidermis. Almost all of the dermal nevomelanocytes lack HMB45 protein expression, i.e immunohistochemical maturation. (Original magnifications: A: 20x, B: x200, C: x200, D: x 400, E: x200, and F: 400).

In all cases reviewed, there was a strong and diffuse expression of S100 and Melan-A proteins throughout the entire lesion (percentage of positive cells ranged from 91% to 89.5%). There was a strongly expressed HMB45 protein in the junctional component (lentiginous and nested nevomelanocytes). Within the dermis, HMB45 protein expression decreased, following a gradient from junctional to deeper dermal localization being decreased (occasional positive nevomelanocytes) in the mid dermal portion and nearly completely lost in the deep dermal portions of the nevi, indicating immunohistochemical maturation (a feature favoring of benignancy) of these lesions. The mean value of the percentage of HMB45 positive cells was 39.6 ± 4.5. HMB45 protein expression values were high in the acral and head and neck nevi. The mean values of the percentage of S100 or Melan-A positive cells were significantly higher as compared to those of HMB45 protein (Mann-Whitney U test, p < 0.0001). There was no correlation between the HMB45 protein expression values and the clinical features of the lesions (age and gender of the patient, or site, size of the lesions). Ki-67 labeling index was extremely low in NOSS (Ki-67 mean labeling index was 1.1 ± 0.1, a feature favoring of benignancy). A summary of these findings is shown in Table 2 and Figs. 1–3. A summary of these findings is shown in Table 2 and Figs. 1–3.

DiscussionNOSS show alarming histological features and therefore they continue to be a diagnostic pitfall for the practicing pathologist. Although these features have been previously described,1–5 the immunophenotypic profile of NOSS has not been fully characterized. This study demonstrates several observations: i) all of the cases of NOSS showed some concerning histological features and therefore can be easily overcalled as atypical nevi or even melanomas, ii) all of the cases of NOSS showed prominent HMB45 protein expression in the lentiginous and nested component, and iii) all of the cases of NOSS showed evidence of immunohistochemical maturation.

All of the cases of NOSS showed some concerning histological featuresThe histological characteristics of NOSS in this series concur with previous studies.1–5 Despite these worrisome morphological changes, histological features favoring benignancy included the presence of symmetry, circumscription, the predominance of the nested over the lentiginous component, dermal maturation, and lack of notable upward scatter of the nevomelanocytes or significant mitotic activity.4,6 In NOSS, the possible pathogenetic mechanisms underlying the development of alarming histological features (large, crowded, dyshesive nests, and low-level intraepidermal pagetoid spread) include the underlying site-specific hormonal effects10 (NOSS of the milk line or in the genital sites), site-related repetitive traumas (NOSS of the acral and head and neck regions), site related-UV irradiation (NOSS of the head and neck regions),11 alteration of the melanocytic–keratinocytic interactions,10 and some mutational changes.

The dyshesive nested pattern in NOSS, may be due to downregulation or loss of cell adhesion molecules. The alarming histological futures of NOSS in the head and neck regions may be due to the effects of UV irradiation. In support, UV irradiation can induce morphological changes reminiscent of melanoma by enhancing the proliferative and metabolic activities of the nevomelanocytes.11

The presence of low-level pagetoid spread (in acral and genital nevi) may represent “a passive ‘passenger’ mechanism via the maturing keratinocytic flow”12,13 or reflect alteration of the melanocytic–keratinocytic interactions.10 The pagetoid single cell spread of the nevomelanocytes into the spinous layer (pagetoid melanocytosis) can be marked in some acral nevi, also known as MANIAC (Melanocytic Acral Nevi with Intraepithelial Ascent of Cells). These nevi are separated from acral melanomas by several clues including the fact that these pagetoid nevomelanocytes lack cytological atypia and they do not spread beyond the center of the lesion. MANIAC generally shows symmetry, circumscription, and maturation of the lesions with descending into the dermis.14,15

All of the cases of NOSS showed prominent HMB45 protein expression in the lentiginous and nested componentThis study reports strong HMB45 protein expressionin the junctional component of NOSS, indicating that these nevi focally have an activated phenotype with active melanosome formation. The mechanisms underlying this activated phenotype include the release of melanocytic growth factors.16 This study also revealed a gradual decrease in the HMB45 protein expression, following a gradient from junctional to deeper dermal localization in NOSS, i.e. immunohistochemical maturation. The HMB-45 reactivitycan attest to the presence or absence of ‘‘immunohistochemical maturation’’ of a given melanocytic lesion. The activated junctional or superficial, type A melanocytes (epithelioid cells) express HMB45, while the deeply located type C melanocytes (spindle cells) do not express this antibody.17–19 In this author's view, the extremely low Ki-67 labeling index together with immunohistochemical maturation are important features that favor the benignancy of a given melanocytic lesion (at the special sites) with alarming histological features. The decreasing staining HMB45 pattern, as well as the lack of Ki-67 in the deep parts of the lesional cells of NOSS, has previously been successfully studied as a diagnostic clue of nevus versus melanoma.20–23

To conclude, the diagnosis of NOSS should be considered in any nevomelanocytic proliferation occurring at particular sites (head and neck region, milk line, genitalia, perineum, conjunctiva and acral sites. The expression of HMB45 protein in NOSS indicates that their nevomelanocytic cells have an activated phenotype. The decreased HMB45 protein expression following a gradient from junctional to deeper dermal localization in NOSS is indicative of their immunohistochemical maturation.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Hussein MRA. Nevos melanocíticos con atipia relacionada con su localización: presentación de una serie de casos y caracterización de su perfil inmunohistoquímico. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2021;112:242–249.