To develop evidence- and experience-based recommendations for the management of psoriasis during preconception, pregnancy, postpartum, and breastfeeding.

MethodsThe nominal group technique and the Delphi method were used. Fifteen experts (12 dermatologists, 2 of whom were appointed coordinators; 1 rheumatologist; and 2 gynecologists) were selected to form an expert panel. Following a systematic review of the literature on fertility, pregnancy, postpartum, and breastfeeding in women with psoriasis, the coordinators drew up a series of preliminary recommendations for discussion by the panel at a nominal group meeting. The experts defined the scope, sections, and intended users of the statement and prepared a final list of recommendations. Consensus was obtained using a Delphi process in which an additional 51 dermatologists rated their level of agreement with each recommendation on a scale of 1 (total disagreement) to 10 (total agreement). Consensus was defined by a score of 7 or higher assigned by at least 70% of participants. Level of evidence and strength of recommendation were reported using the Oxford Center for Evidence-Based Medicine categories. The final statement was approved by the expert panel.

ResultsThe resulting consensus statement includes 23 recommendations on preconception (fertility and contraception), pregnancy (planning, pharmacological management, and follow-up), and breastfeeding (management and follow-up). Consensus was achieved for all recommendations generated except one.

ConclusionsThese recommendations for the better management of psoriasis in women of childbearing age could improve outcomes and prognosis.

Desarrollar recomendaciones basadas en la mejor evidencia y experiencia sobre el manejo de pacientes con psoriasis durante la edad fértil, el embarazo, el posparto y la lactancia.

MétodosSe siguió la metodología de grupos nominales y Delphi. Se seleccionó un grupo director de expertos (12 dermatólogos —de los cuales 2 fueron los coordinadores—, 1 reumatólogo, 2 ginecólogos). Se realizó una revisión sistemática de la literatura sobre fertilidad, embarazo, posparto y lactancia en pacientes con psoriasis. Con esta información los coordinadores generaron una serie de recomendaciones preliminares. Todo ello se presentó y discutió con el resto de expertos en una reunión de grupo nominal donde se definió el alcance, los usuarios, los apartados del documento, y donde se generaron las recomendaciones definitivas. El grado de acuerdo con las recomendaciones se votó siguiendo la metodología Delphi, que se extendió a 51 dermatólogos más, según una escala de 1 (total desacuerdo) a 10 (total acuerdo), definiéndose el acuerdo como una puntuación ≥ 7 por al menos el 70% de los participantes. El nivel de evidencia y el grado de recomendación se clasificaron según el modelo del Center for Evidence Based Medicine de Oxford. El documento completo final fue aprobado por el panel de expertos.

ResultadosSe generaron 23 recomendaciones sobre el periodo pre-concepcional (fertilidad y anticoncepción), el embarazo (planificación, manejo farmacológico y seguimiento) y la lactancia (manejo y seguimiento). Todas las recomendaciones menos una alcanzaron el nivel de acuerdo definido.

ConclusionesEn los pacientes con psoriasis en edad fértil estas recomendaciones pueden mejorar el manejo, los resultados y el pronóstico.

Psoriasis is a very common disease1,2 with 2 peaks in incidence—one between age 15 and 30 years and the other between 50 and 60 years—although the disease first manifests before age 40 years in more than 75% of cases.3,4 In clinical practice, a large percentage of patients are of reproductive age, and psoriasis and/or its treatments can affect fertility, pregnancy, postpartum, and breastfeeding and vice versa.5–8 Owing to its severity, or to pain or embarrassment in the case of genital involvement, psoriasis may be associated with fertility problems, both in men and in women.9–11 Some treatments of psoriasis, including tazarotene and acitretin,12,13 are potentially teratogenic and are therefore contraindicated during pregnancy. It has also been reported that the disease worsens in 40% to 80% of patients a few weeks after delivery14 and that the children of mothers who have been in treatment with monoclonal antibodies that cross the placenta during the third trimester are at greater risk of infection and, therefore, require specific monitoring and management.15

Awareness of these problems and a suitable approach to preventing them or treating them early and efficiently should form part of the knowledge and skills of health professionals involved in the management of affected patients.16 In addition, these problems are very relevant for psoriasis patients themselves.16

The objective of this consensus statement is to generate a series of recommendations aimed at improving management of patients of reproductive age with psoriasis. The statement covers fertility, pregnancy, postpartum, and breastfeeding. We believe that the recommendations are of considerable interest for health professionals involved in treating patients with psoriasis, namely, dermatologists, gynecologists, primary care physicians, and nurses.

MethodsStudy DesignThis document was promoted by the Psoriasis Working Group of the Spanish Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (Academia Española de Dermatología y Venereología [AEDV]). The consensus statement was drafted following the nominal group technique and the Delphi method, with the help of a systematic review of the literature.17 The project was managed in full agreement with the principles set out in the Declaration of Helsinki and in line with current norms of Good Clinical Practice.

Selection of ParticipantsThe participants selected formed a multidisciplinary group comprising 12 dermatologists (2 of whom were the coordinators), 1 rheumatologist, and 2 gynecologists with experience and interest in the subject area. With help from methodologists, the coordinators defined the objectives, scope, users, and sections of the document. It was decided to address 3 broad areas: (a) reproductive age; (b) pregnancy and postpartum; and (c) breastfeeding and perinatal care.

Systematic Review of the Literature and Preliminary RecommendationsA systematic review of the literature was performed to assess fertility, delivery, and breastfeeding in patients with psoriasis. An expert documentalist designed the search strategies for the PubMed, EMBASE, and Cochrane library databases (from baseline to November 2018) using Medical Subject Headings and free text terms. In order to be included, studies had to fulfil the following criteria: (1) they had to include patients with psoriasis; (2) they had to provide data on pregnancy, breastfeeding, and postpartum (e.g., prevalence, interventions, prognoses); and (3) they had to be a meta-analysis, systematic review of the literature, randomized clinical trial, or observational study. Two reviewers independently selected articles and collected data. Finally, a secondary search for articles was carried out. The quality of the studies was evaluated using the 2011 classification of the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine.18 This information enabled the coordinators to generate a series of preliminary recommendations.

Meeting of the Nominal GroupThe objectives, scope, users, and sections of the document were confirmed at the meeting of the nominal group. The results of the systematic literature review were then presented and discussed, as were the provisional recommendations. Finally, the definitive recommendations were established.

Delphi ProcessThe definitive recommendations were assessed using the Delphi process to establish the level of agreement (LA) with them. This stage was carried out online. The recommendations were sent to the expert panel and to 120 dermatologists. The vote was based on a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (completely disagree) to 10 (completely agree). Agreement was defined as a score of ≥ 7 from at least 70% of the participants. The recommendations with an LA < 70% were evaluated and, if applicable, re-edited and voted on in a second Delphi round. It was possible to include new recommendations in the first Delphi round.

Edition of the Final DocumentThe definitive document was drafted based on the systematic review of the literature, the decisions of the nominal group, and the Delphi process. In addition to the LA, each of the recommendations was assigned a level of evidence (LE) and a grade of recommendation (GR) according to the recommendations for evidence-based medicine of the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine.18 The final version of the document was sent to the experts for a concluding evaluation and comments.

ResultsSystematic Review of the Literature and Delphi ProcessAfter elimination of duplicates, 610 references were recovered. Of these, 49 were eventually included (Fig. 1 and other results in Appendix A, Supplementary material).

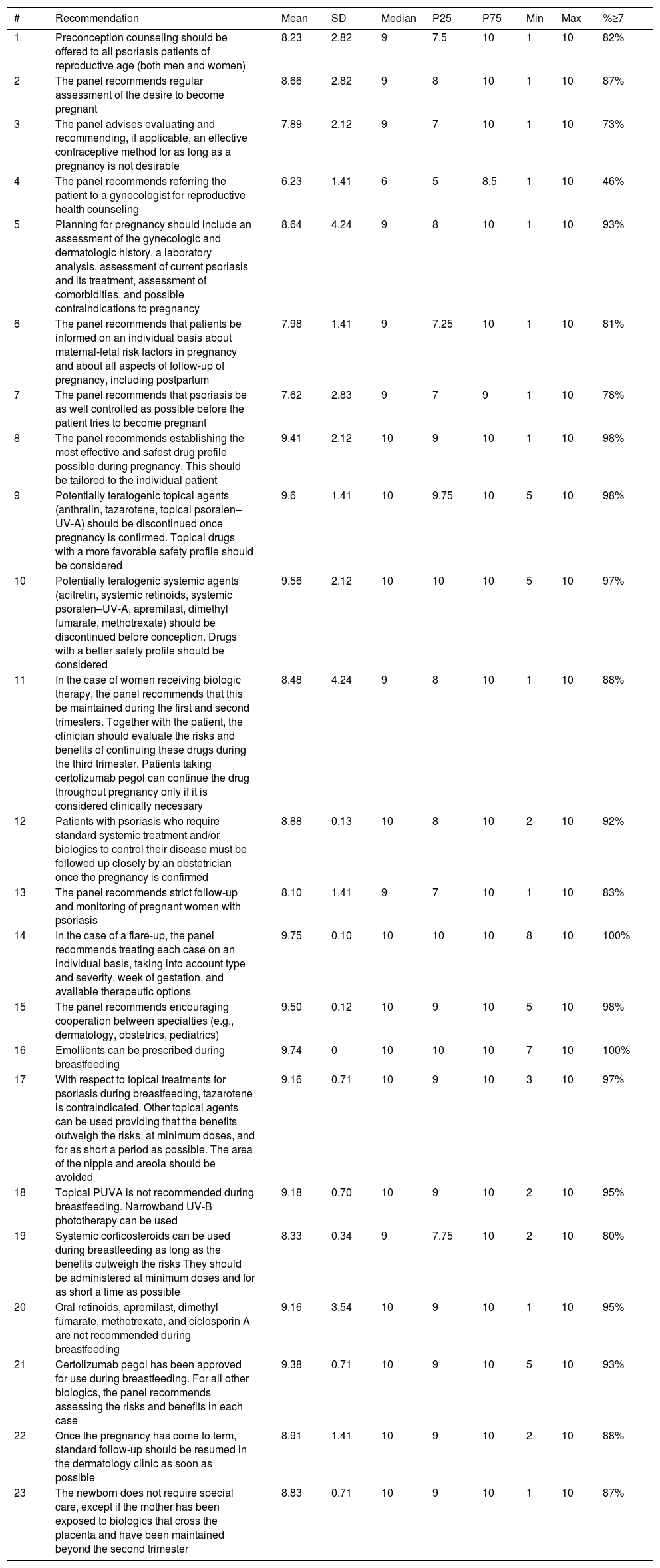

A total of 23 recommendations were generated. The Delphi response rate was 50%. In the first Delphi round, the LA was sufficient for all recommendations but one. The recommendation for which a sufficient LA was not reached was excluded. The results are shown in Table 1.

Definitive Recommendations and Results of the Delphi Process.

| # | Recommendation | Mean | SD | Median | P25 | P75 | Min | Max | %≥7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Preconception counseling should be offered to all psoriasis patients of reproductive age (both men and women) | 8.23 | 2.82 | 9 | 7.5 | 10 | 1 | 10 | 82% |

| 2 | The panel recommends regular assessment of the desire to become pregnant | 8.66 | 2.82 | 9 | 8 | 10 | 1 | 10 | 87% |

| 3 | The panel advises evaluating and recommending, if applicable, an effective contraceptive method for as long as a pregnancy is not desirable | 7.89 | 2.12 | 9 | 7 | 10 | 1 | 10 | 73% |

| 4 | The panel recommends referring the patient to a gynecologist for reproductive health counseling | 6.23 | 1.41 | 6 | 5 | 8.5 | 1 | 10 | 46% |

| 5 | Planning for pregnancy should include an assessment of the gynecologic and dermatologic history, a laboratory analysis, assessment of current psoriasis and its treatment, assessment of comorbidities, and possible contraindications to pregnancy | 8.64 | 4.24 | 9 | 8 | 10 | 1 | 10 | 93% |

| 6 | The panel recommends that patients be informed on an individual basis about maternal-fetal risk factors in pregnancy and about all aspects of follow-up of pregnancy, including postpartum | 7.98 | 1.41 | 9 | 7.25 | 10 | 1 | 10 | 81% |

| 7 | The panel recommends that psoriasis be as well controlled as possible before the patient tries to become pregnant | 7.62 | 2.83 | 9 | 7 | 9 | 1 | 10 | 78% |

| 8 | The panel recommends establishing the most effective and safest drug profile possible during pregnancy. This should be tailored to the individual patient | 9.41 | 2.12 | 10 | 9 | 10 | 1 | 10 | 98% |

| 9 | Potentially teratogenic topical agents (anthralin, tazarotene, topical psoralen–UV-A) should be discontinued once pregnancy is confirmed. Topical drugs with a more favorable safety profile should be considered | 9.6 | 1.41 | 10 | 9.75 | 10 | 5 | 10 | 98% |

| 10 | Potentially teratogenic systemic agents (acitretin, systemic retinoids, systemic psoralen–UV-A, apremilast, dimethyl fumarate, methotrexate) should be discontinued before conception. Drugs with a better safety profile should be considered | 9.56 | 2.12 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 5 | 10 | 97% |

| 11 | In the case of women receiving biologic therapy, the panel recommends that this be maintained during the first and second trimesters. Together with the patient, the clinician should evaluate the risks and benefits of continuing these drugs during the third trimester. Patients taking certolizumab pegol can continue the drug throughout pregnancy only if it is considered clinically necessary | 8.48 | 4.24 | 9 | 8 | 10 | 1 | 10 | 88% |

| 12 | Patients with psoriasis who require standard systemic treatment and/or biologics to control their disease must be followed up closely by an obstetrician once the pregnancy is confirmed | 8.88 | 0.13 | 10 | 8 | 10 | 2 | 10 | 92% |

| 13 | The panel recommends strict follow-up and monitoring of pregnant women with psoriasis | 8.10 | 1.41 | 9 | 7 | 10 | 1 | 10 | 83% |

| 14 | In the case of a flare-up, the panel recommends treating each case on an individual basis, taking into account type and severity, week of gestation, and available therapeutic options | 9.75 | 0.10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 8 | 10 | 100% |

| 15 | The panel recommends encouraging cooperation between specialties (e.g., dermatology, obstetrics, pediatrics) | 9.50 | 0.12 | 10 | 9 | 10 | 5 | 10 | 98% |

| 16 | Emollients can be prescribed during breastfeeding | 9.74 | 0 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 7 | 10 | 100% |

| 17 | With respect to topical treatments for psoriasis during breastfeeding, tazarotene is contraindicated. Other topical agents can be used providing that the benefits outweigh the risks, at minimum doses, and for as short a period as possible. The area of the nipple and areola should be avoided | 9.16 | 0.71 | 10 | 9 | 10 | 3 | 10 | 97% |

| 18 | Topical PUVA is not recommended during breastfeeding. Narrowband UV-B phototherapy can be used | 9.18 | 0.70 | 10 | 9 | 10 | 2 | 10 | 95% |

| 19 | Systemic corticosteroids can be used during breastfeeding as long as the benefits outweigh the risks They should be administered at minimum doses and for as short a time as possible | 8.33 | 0.34 | 9 | 7.75 | 10 | 2 | 10 | 80% |

| 20 | Oral retinoids, apremilast, dimethyl fumarate, methotrexate, and ciclosporin A are not recommended during breastfeeding | 9.16 | 3.54 | 10 | 9 | 10 | 1 | 10 | 95% |

| 21 | Certolizumab pegol has been approved for use during breastfeeding. For all other biologics, the panel recommends assessing the risks and benefits in each case | 9.38 | 0.71 | 10 | 9 | 10 | 5 | 10 | 93% |

| 22 | Once the pregnancy has come to term, standard follow-up should be resumed in the dermatology clinic as soon as possible | 8.91 | 1.41 | 10 | 9 | 10 | 2 | 10 | 88% |

| 23 | The newborn does not require special care, except if the mother has been exposed to biologics that cross the placenta and have been maintained beyond the second trimester | 8.83 | 0.71 | 10 | 9 | 10 | 1 | 10 | 87% |

Recommendation 1. Preconception counseling should be offered to all psoriasis patients of reproductive age (both men and women) (LE 2b; GR B; LA 82%).

Preconception counseling should always be offered so that patients with psoriasis can make informed decisions together with the dermatologist and also to avoid, as far as possible, unnecessary delays in conception.

Psoriasis is not a contraindication for gestation, although pregnancy can affect psoriasis; in turn, psoriasis (and its treatment) may be a risk factor for the course of the pregnancy.4,14,19–25

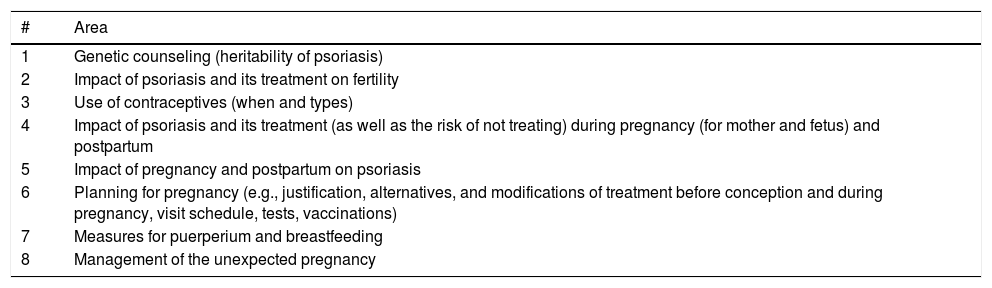

Preconception counseling (Table 2) ranges from information on the impact of the disease on fertility and pregnancy to the approach to an unexpected pregnancy and genetic counseling.26,27 This in turn should be adjusted to the patient’s characteristics and involve the partner where possible. Preconception counseling should be repeated periodically.

Areas to Be Covered in Preconception Counseling.

| # | Area |

|---|---|

| 1 | Genetic counseling (heritability of psoriasis) |

| 2 | Impact of psoriasis and its treatment on fertility |

| 3 | Use of contraceptives (when and types) |

| 4 | Impact of psoriasis and its treatment (as well as the risk of not treating) during pregnancy (for mother and fetus) and postpartum |

| 5 | Impact of pregnancy and postpartum on psoriasis |

| 6 | Planning for pregnancy (e.g., justification, alternatives, and modifications of treatment before conception and during pregnancy, visit schedule, tests, vaccinations) |

| 7 | Measures for puerperium and breastfeeding |

| 8 | Management of the unexpected pregnancy |

While psoriasis is not a frequently reported problem, its severity or the consequences of genital involvement (pain or embarrassment) mean that it may be associated with fertility problems.9,22,25,28–36 Some of the drugs used to treat psoriasis may also affect fertility, although this has not been demonstrated.10,37–40

Recommendation 2. The panel recommends regular assessment of the desire to become pregnant (LE 5; GR D; LA 87%).

This recommendation applies to all patients of reproductive age (both sexes), especially those who are receiving or who are candidates for long-term systemic treatment.

Recommendation 3. The panel recommends evaluating and recommending, if applicable, an effective contraceptive method panel for as long as pregnancy is not desirable (LE 2b; GR B; LA 73%).

We should recommend the use of effective contraceptive methods to both men and women, for as long as a pregnancy is not envisaged or when it is preferable to postpone it (e.g., owing to the severity of the disease, initiation of a teratogenic treatment).

Combined hormonal contraception is the most efficacious method,41 except in the case of a contraindication.42 However, the panel recommends tailoring the method to the individual case and referring the patient to a gynecologist or primary care if necessary.

While assisted reproduction is considered a gynecologic area, dermatologists who care for patients undergoing this process should be aware of the general aspects of the procedures in order to be able to provide appropriate information. The LA for the recommendation formulated with respect to this area (Recommendation 4, Table 1) was insufficient (see Discussion).

Planning for PregnancyRecommendation 4. The panel recommends referring the patient to a gynecologist for reproductive counseling (LE 5; GR D; LA 46%).

Recommendation 5. Planning for pregnancy should include an assessment of the gynecologic and dermatologic history, a laboratory analysis, assessment of current psoriasis and its treatment, assessment of comorbidities, and possible contraindications to pregnancy (LE 5; GR D; LA 93%).

Recommendation 6. The panel recommends that patients be informed on an individual basis about maternal-fetal risk factors in pregnancy and about all aspects of follow-up of the pregnancy, including postpartum (LE 5; GR D; LA 81%).

Recommendation 7. The panel recommends that psoriasis is controlled as well as possible before the patient tries to become pregnant (LE 2b; GR B; LA 78%).

Pregnancy can affect psoriasis, and this (and its treatment) may be a risk factor for the course of the pregnancy.4,14,19–25 Control of psoriasis and preconception use of drugs with a low risk for the fetus make it possible to reduce the risk of maternal-fetal complications. Therefore, it is essential to plan the pregnancy and ensure collaboration with a gynecologist and primary care physician.

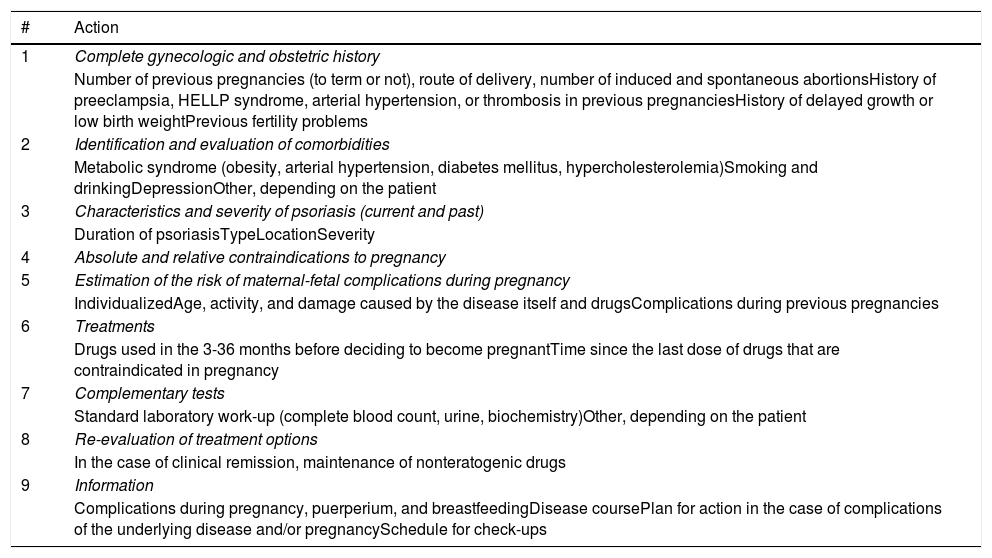

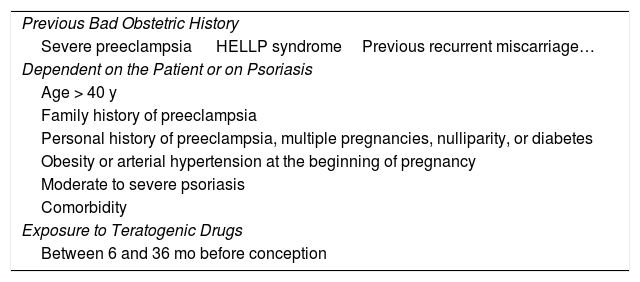

Planning (Tables 3 and 4) should involve a personalized preconception assessment covering the patient’s complete gynecologic and obstetric history, contraindications for pregnancy, and risk factors for maternal-fetal complications,22,25 including the drugs used before and during pregnancy (Table 5).

Planning the Pregnancy.

| # | Action |

|---|---|

| 1 | Complete gynecologic and obstetric history |

| Number of previous pregnancies (to term or not), route of delivery, number of induced and spontaneous abortionsHistory of preeclampsia, HELLP syndrome, arterial hypertension, or thrombosis in previous pregnanciesHistory of delayed growth or low birth weightPrevious fertility problems | |

| 2 | Identification and evaluation of comorbidities |

| Metabolic syndrome (obesity, arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hypercholesterolemia)Smoking and drinkingDepressionOther, depending on the patient | |

| 3 | Characteristics and severity of psoriasis (current and past) |

| Duration of psoriasisTypeLocationSeverity | |

| 4 | Absolute and relative contraindications to pregnancy |

| 5 | Estimation of the risk of maternal-fetal complications during pregnancy |

| IndividualizedAge, activity, and damage caused by the disease itself and drugsComplications during previous pregnancies | |

| 6 | Treatments |

| Drugs used in the 3-36 months before deciding to become pregnantTime since the last dose of drugs that are contraindicated in pregnancy | |

| 7 | Complementary tests |

| Standard laboratory work-up (complete blood count, urine, biochemistry)Other, depending on the patient | |

| 8 | Re-evaluation of treatment options |

| In the case of clinical remission, maintenance of nonteratogenic drugs | |

| 9 | Information |

| Complications during pregnancy, puerperium, and breastfeedingDisease coursePlan for action in the case of complications of the underlying disease and/or pregnancySchedule for check-ups |

Abbreviations: HELLP, hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, low platelet count.

Risk Factors for Maternal-Fetal Complications in Patients With Psoriasis.

| Previous Bad Obstetric History |

| Severe preeclampsia HELLP syndromePrevious recurrent miscarriage… |

| Dependent on the Patient or on Psoriasis |

| Age > 40 y |

| Family history of preeclampsia |

| Personal history of preeclampsia, multiple pregnancies, nulliparity, or diabetes |

| Obesity or arterial hypertension at the beginning of pregnancy |

| Moderate to severe psoriasis |

| Comorbidity |

| Exposure to Teratogenic Drugs |

| Between 6 and 36 mo before conception |

Abbreviation: HELLP, hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, low platelet count.

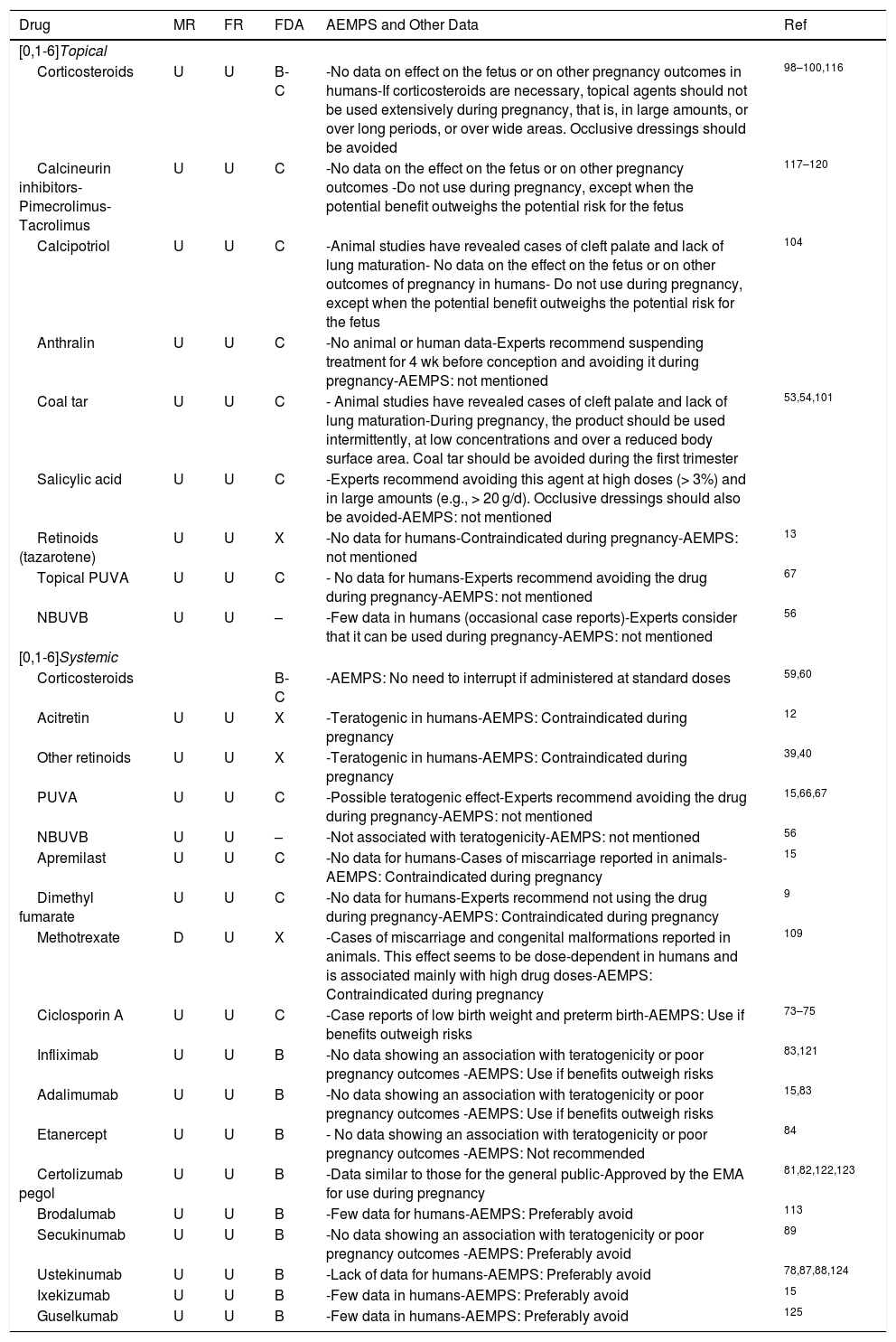

Safety of Commonly Used Dermatologic Drugs With Respect to Fertility and Pregnancy.

| Drug | MR | FR | FDA | AEMPS and Other Data | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [0,1-6]Topical | |||||

| Corticosteroids | U | U | B-C | -No data on effect on the fetus or on other pregnancy outcomes in humans-If corticosteroids are necessary, topical agents should not be used extensively during pregnancy, that is, in large amounts, or over long periods, or over wide areas. Occlusive dressings should be avoided | 98–100,116 |

| Calcineurin inhibitors-Pimecrolimus-Tacrolimus | U | U | C | -No data on the effect on the fetus or on other pregnancy outcomes -Do not use during pregnancy, except when the potential benefit outweighs the potential risk for the fetus | 117–120 |

| Calcipotriol | U | U | C | -Animal studies have revealed cases of cleft palate and lack of lung maturation- No data on the effect on the fetus or on other outcomes of pregnancy in humans- Do not use during pregnancy, except when the potential benefit outweighs the potential risk for the fetus | 104 |

| Anthralin | U | U | C | -No animal or human data-Experts recommend suspending treatment for 4 wk before conception and avoiding it during pregnancy-AEMPS: not mentioned | |

| Coal tar | U | U | C | - Animal studies have revealed cases of cleft palate and lack of lung maturation-During pregnancy, the product should be used intermittently, at low concentrations and over a reduced body surface area. Coal tar should be avoided during the first trimester | 53,54,101 |

| Salicylic acid | U | U | C | -Experts recommend avoiding this agent at high doses (> 3%) and in large amounts (e.g., > 20 g/d). Occlusive dressings should also be avoided-AEMPS: not mentioned | |

| Retinoids (tazarotene) | U | U | X | -No data for humans-Contraindicated during pregnancy-AEMPS: not mentioned | 13 |

| Topical PUVA | U | U | C | - No data for humans-Experts recommend avoiding the drug during pregnancy-AEMPS: not mentioned | 67 |

| NBUVB | U | U | – | -Few data in humans (occasional case reports)-Experts consider that it can be used during pregnancy-AEMPS: not mentioned | 56 |

| [0,1-6]Systemic | |||||

| Corticosteroids | B-C | -AEMPS: No need to interrupt if administered at standard doses | 59,60 | ||

| Acitretin | U | U | X | -Teratogenic in humans-AEMPS: Contraindicated during pregnancy | 12 |

| Other retinoids | U | U | X | -Teratogenic in humans-AEMPS: Contraindicated during pregnancy | 39,40 |

| PUVA | U | U | C | -Possible teratogenic effect-Experts recommend avoiding the drug during pregnancy-AEMPS: not mentioned | 15,66,67 |

| NBUVB | U | U | – | -Not associated with teratogenicity-AEMPS: not mentioned | 56 |

| Apremilast | U | U | C | -No data for humans-Cases of miscarriage reported in animals-AEMPS: Contraindicated during pregnancy | 15 |

| Dimethyl fumarate | U | U | C | -No data for humans-Experts recommend not using the drug during pregnancy-AEMPS: Contraindicated during pregnancy | 9 |

| Methotrexate | D | U | X | -Cases of miscarriage and congenital malformations reported in animals. This effect seems to be dose-dependent in humans and is associated mainly with high drug doses-AEMPS: Contraindicated during pregnancy | 109 |

| Ciclosporin A | U | U | C | -Case reports of low birth weight and preterm birth-AEMPS: Use if benefits outweigh risks | 73–75 |

| Infliximab | U | U | B | -No data showing an association with teratogenicity or poor pregnancy outcomes -AEMPS: Use if benefits outweigh risks | 83,121 |

| Adalimumab | U | U | B | -No data showing an association with teratogenicity or poor pregnancy outcomes -AEMPS: Use if benefits outweigh risks | 15,83 |

| Etanercept | U | U | B | - No data showing an association with teratogenicity or poor pregnancy outcomes -AEMPS: Not recommended | 84 |

| Certolizumab pegol | U | U | B | -Data similar to those for the general public-Approved by the EMA for use during pregnancy | 81,82,122,123 |

| Brodalumab | U | U | B | -Few data for humans-AEMPS: Preferably avoid | 113 |

| Secukinumab | U | U | B | -No data showing an association with teratogenicity or poor pregnancy outcomes -AEMPS: Preferably avoid | 89 |

| Ustekinumab | U | U | B | -Lack of data for humans-AEMPS: Preferably avoid | 78,87,88,124 |

| Ixekizumab | U | U | B | -Few data in humans-AEMPS: Preferably avoid | 15 |

| Guselkumab | U | U | B | -Few data in humans-AEMPS: Preferably avoid | 125 |

Abbreviations: AEMPS, Agencia Española del Medicamento y Productos Sanitarios (Spanish Agency of Medicines and Medical Devices); D, doubtful; FDA, Food and Drug Administration; FR, fetal risk; MR, maternal risk; NBUVB, narrowband UV-B phototherapy; PUVA, psoralen–UV-A; U, unknown.

Psoriasis improves in 33%-60% of women during pregnancy,4,14,19 remains unchanged in 25%, and worsens in 25%.14 However, 40%-88% experience a flare-up after delivery.4,6,14,19,24,43–45

Data on the effect of psoriasis in pregnancy, childbirth, and the newborn are somewhat controversial.5,25,34,46–48 Some studies associate poor results specifically with patients who have moderate to severe psoriasis.7,48 At present, there are no data suggesting an association between psoriasis and the development of congenital malformations,7,49 and while findings are heterogeneous, there does seem to be an association between psoriasis and the development of diabetes and gestational arterial hypertension.7,48

Finally, it is also essential to ensure that psoriasis is inactive for 3-4 months, using nonteratogenic drugs. If this is not possible, then the lowest degree of activity possible should be sought on an individual basis.

Pregnancy and Follow-upPregnancyRecommendation 8. The panel recommends establishing the most effective and safest pharmacological profile possible during pregnancy. This should be tailored to the individual patient (LE 5; GR D; LA 98%).

Knowledge of safety of medications is one of the pillars of effective and safe medical and obstetric care (Table 5). However, we lack sufficient evidence to provide robust, explicit recommendations for all drugs.9,50,51 Therefore, during pregnancy, drugs should be prescribed with caution, after performing a meticulous evaluation of the risks and benefits for each patient and taking informed decisions, which should be agreed with the patient.40

Topical DrugsRecommendation 9. Potentially teratogenic topical agents (anthralin, tazarotene, topical psoralen–UV-A [PUVA]) should be discontinued once pregnancy is confirmed. Topical drugs with a more favorable safety profile should be considered (LE 3a; GR C; LA 98%).

The panel also considers it important to assess the risk-benefit ratio on an individual basis. In the case of topical drugs with a more favorable safety profile, these should be prescribed at the lowest dose possible over as small an area as possible for as short a time as possible. Occlusive dressings should be avoided (Table 5).

The only association reported for topical corticosteroids is between low birth weight and the use of high- and very-high-potency corticosteroids, especially when the duration of exposure and cumulative dose are considerable.15,52 Topical calcineurin inhibitors15 and calcipotriol have been shown to be safe. However, maternal vitamin D deficiency can be associated with a teratogenic risk. As for coal tar, there are no data to suggest teratogenicity or poor pregnancy outcome in humans, although cases of malformation have been reported in animals.15,53,54 A moderate amount of topical salicylic acid (9%-25%) can be absorbed systemically, and it has been reported that use of this agent during the first trimester could be associated with an increased risk of gastroschisis.15,55 It is important to note that phototherapy with narrowband UV-B radiation is safe during pregnancy.56

While teratogenicity and poor pregnancy outcome have not been reported with anthralin, this agent should be suspended 4 weeks before conception.15 As for topical tazarotene, it is estimated that 6% is absorbed systemically57,58; in addition, systemic absorption may increase owing to individual factors, such as damage to the skin barrier. Although there are no data pointing to embryopathy, this drug is contraindicated during pregnancy. Similarly, topical PUVA drugs are not recommended during pregnancy.15

Systemic DrugsRecommendation 10. Potentially teratogenic systemic agents (acitretin, systemic retinoids, systemic PUVA, apremilast, dimethyl fumarate, methotrexate) should be discontinued before conception. Prescription of topical and/or systemic and/or phototherapy with a better safety profile should be considered (LE 3a; GR C; LA 97%).

No cases of congenital malformations or other relevant problems have been reported for systemic corticosteroids.59–61

Acitretin is a potent teratogen in humans.62,63 It can be detected in blood 2 months after the last dose, although in some circumstances, such as the presence of alcohol, it can be converted to etretinate and be detected for 120 days. Therefore, it is usually recommended to suspend this drug for up to 2 years before conception. Cases should be managed on an individual basis.15,64,65 Other oral retinoids, such as alitretinoin and isotretinoin are also contraindicated during pregnancy.39,40

Potential associations between systemic PUVA agents and teratogenic complications remain unclear15,66,67; therefore, these agents are contraindicated during pregnancy. Narrowband UV-B phototherapy, on the other hand, has proven to be safe during pregnancy.56

No data are currently available on the teratogenic potential of apremilast in humans, although abortion and low birth weight have been reported in animals; consequently, its use is contraindicated in pregnancy.15 Similarly, the lack of data in humans for dimethyl fumarate means that this agent is not recommended.9

Animal data show that, in addition to causing abortion, methotrexate is a teratogenic drug. However, various observational studies suggest that defects are induced with doses of methotrexate greater than 10 mg/wk and that the critical period would be 6-8 weeks after conception.68–72 This drug is currently contraindicated in pregnancy and should be suspended 3 months before conception.

Finally, ciclosporin A has been associated with a greater risk of low birth weight and preterm birth in pregnant women who have received solid organ transplants, but not with a greater risk of congenital abnormalities.73–75

Biologic TherapyRecommendation 11. In the case of women receiving biologic therapy, the panel recommends that this be maintained during the first and second trimesters. Together with the patient, the clinician should evaluate the risks and benefits of continuing these drugs during the third trimester. Patients taking certolizumab pegol can continue the drug throughout pregnancy only if it is considered clinically necessary (LE 3a; GR C; LA 88%).

In the case of monoclonal antibodies, transfer of immunoglobulin (Ig) G antibodies begins in the second trimester by means of binding to placental Fc receptors.9 Nevertheless, not all monoclonal antibodies have the same affinity for binding to these receptors. IgG1 (adalimumab, infliximab, secukinumab, ustekinumab, guselkumab), IgG2 (brodalumab), and IgG4 (ixekizumab) probably cross the placenta in a similar fashion.76–78 Levels of infliximab have even been detected in newborns up to 6 months after birth. However, while etanercept has lower affinity79,80, reduced or no placental transfer has been reported mainly for certolizumab pegol (which lacks an Fc receptor).81,82

No associations have been reported for anti-TNF-α agents with respect to teratogenic capacity and poor pregnancy outcomes (including maternal infections).83,84 Data on certolizumab pegol from prospective studies with more than 500 pregnant women do not show an increased risk of malformation or miscarriage.85,86 Therefore, the regulatory agencies have approved certolizumab pegol for use during pregnancy and breastfeeding.

No or few data are available for brodalumab, ustekinumab,78,87,88 secukinumab,89 ixekizumab, and guselkumab.

Follow-upRecommendation 12. Patients with psoriasis who require standard systemic treatments and/or biologics to control their disease must be followed up closely by an obstetrician once the pregnancy is confirmed (LE 5; GR D; LA 92%).

Where possible, follow-up should be in a high-risk pregnancy unit (see section on multidisciplinary care, Recommendation 15).

Recommendation 13. The panel recommends strict follow-up and monitoring of pregnant women with psoriasis (LE 5; GR D; LA 83%).

As in the case of any other patient with psoriasis, pregnant women should be evaluated in terms of their disease.

The frequency of visits depends on the obstetric assessment and the type and status of psoriasis. In general, for a clinically stable patient with low or no disease activity, visits can be every 4-6 weeks during the first 2 trimesters, increasing in frequency from week 32 onward until term, depending on the individual characteristics of the patient. In the case of flare-ups or obstetric complications, the frequency is decided by the attending physicians. Direct and fast access must be ensured for clarification of doubts and resolution of dermatologic or obstetric complications.

Evaluation should be systematic and include a basic physical examination and measurement of arterial blood pressure and weight. The laboratory analysis should include a complete blood count and simple biochemistry work-up with urinalysis (manual and sedimentation). Severity and other disease-related variables are evaluated in line with daily clinical practice.

Finally, the panel considers that the dermatologist should be involved throughout follow-up, irrespective of whether the patient has been followed in a high-risk pregnancy unit or in a general obstetrics clinic.

Recommendation 14. In the case of a flare-up, the panel recommends treating each case on an individual basis, taking into account type and severity, week of gestation, and available therapeutic options (LE 5; GR D; LA 100%).

Therapy should be decided on an individual basis in each case and agreed with the patient and, if necessary, with the gynecologist-obstetrician.

When a pregnant patient with psoriasis develops an infection requiring treatment with antibiotics, the drug chosen should have a good safety profile in pregnancy.90

Recommendation 15. The panel recommends encouraging cooperation between specialties (e.g., dermatology, obstetrics, pediatrics) (LE 5; GR D; LA 98%).

Where possible, every attempt should be made to ensure multidisciplinary care of the patient involving gynecologists experienced in high-risk pregnancies and dermatologists. This approach is greatly facilitated by the electronic medical history. Coordination with the primary care physician is also recommended.

Breastfeeding, Postpartum, and Perinatal CarePsoriasis itself is not a contraindication for breastfeeding, although some of the drugs prescribed to treat it may be (Table 6).91

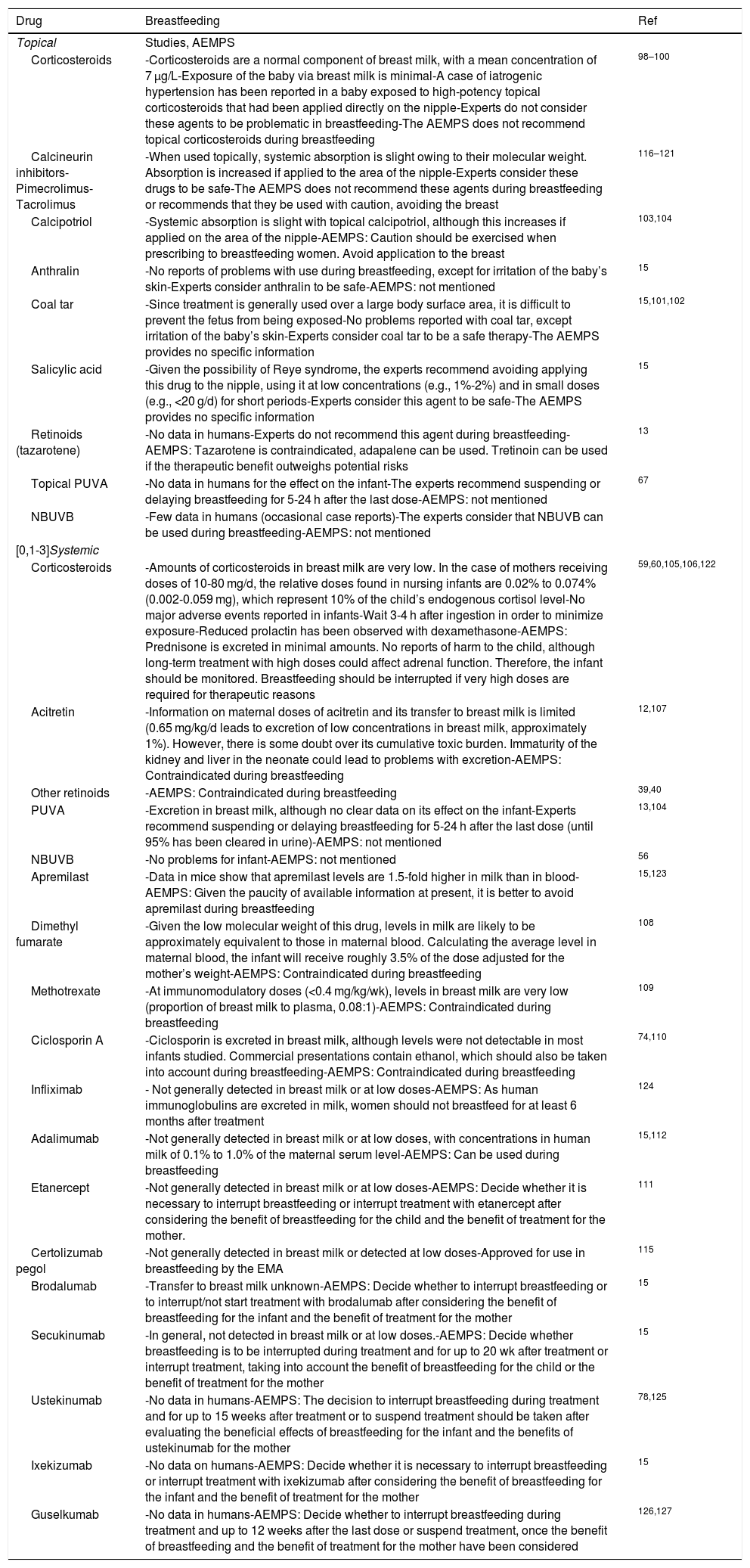

Safety of the Most Commonly Used Dermatologic Drugs During Breastfeeding.

| Drug | Breastfeeding | Ref |

|---|---|---|

| Topical | Studies, AEMPS | |

| Corticosteroids | -Corticosteroids are a normal component of breast milk, with a mean concentration of 7 µg/L-Exposure of the baby via breast milk is minimal-A case of iatrogenic hypertension has been reported in a baby exposed to high-potency topical corticosteroids that had been applied directly on the nipple-Experts do not consider these agents to be problematic in breastfeeding-The AEMPS does not recommend topical corticosteroids during breastfeeding | 98–100 |

| Calcineurin inhibitors-Pimecrolimus-Tacrolimus | -When used topically, systemic absorption is slight owing to their molecular weight. Absorption is increased if applied to the area of the nipple-Experts consider these drugs to be safe-The AEMPS does not recommend these agents during breastfeeding or recommends that they be used with caution, avoiding the breast | 116–121 |

| Calcipotriol | -Systemic absorption is slight with topical calcipotriol, although this increases if applied on the area of the nipple-AEMPS: Caution should be exercised when prescribing to breastfeeding women. Avoid application to the breast | 103,104 |

| Anthralin | -No reports of problems with use during breastfeeding, except for irritation of the baby’s skin-Experts consider anthralin to be safe-AEMPS: not mentioned | 15 |

| Coal tar | -Since treatment is generally used over a large body surface area, it is difficult to prevent the fetus from being exposed-No problems reported with coal tar, except irritation of the baby’s skin-Experts consider coal tar to be a safe therapy-The AEMPS provides no specific information | 15,101,102 |

| Salicylic acid | -Given the possibility of Reye syndrome, the experts recommend avoiding applying this drug to the nipple, using it at low concentrations (e.g., 1%-2%) and in small doses (e.g., <20 g/d) for short periods-Experts consider this agent to be safe-The AEMPS provides no specific information | 15 |

| Retinoids (tazarotene) | -No data in humans-Experts do not recommend this agent during breastfeeding-AEMPS: Tazarotene is contraindicated, adapalene can be used. Tretinoin can be used if the therapeutic benefit outweighs potential risks | 13 |

| Topical PUVA | -No data in humans for the effect on the infant-The experts recommend suspending or delaying breastfeeding for 5-24 h after the last dose-AEMPS: not mentioned | 67 |

| NBUVB | -Few data in humans (occasional case reports)-The experts consider that NBUVB can be used during breastfeeding-AEMPS: not mentioned | |

| [0,1-3]Systemic | ||

| Corticosteroids | -Amounts of corticosteroids in breast milk are very low. In the case of mothers receiving doses of 10-80 mg/d, the relative doses found in nursing infants are 0.02% to 0.074% (0.002-0.059 mg), which represent 10% of the child’s endogenous cortisol level-No major adverse events reported in infants-Wait 3-4 h after ingestion in order to minimize exposure-Reduced prolactin has been observed with dexamethasone-AEMPS: Prednisone is excreted in minimal amounts. No reports of harm to the child, although long-term treatment with high doses could affect adrenal function. Therefore, the infant should be monitored. Breastfeeding should be interrupted if very high doses are required for therapeutic reasons | 59,60,105,106,122 |

| Acitretin | -Information on maternal doses of acitretin and its transfer to breast milk is limited (0.65 mg/kg/d leads to excretion of low concentrations in breast milk, approximately 1%). However, there is some doubt over its cumulative toxic burden. Immaturity of the kidney and liver in the neonate could lead to problems with excretion-AEMPS: Contraindicated during breastfeeding | 12,107 |

| Other retinoids | -AEMPS: Contraindicated during breastfeeding | 39,40 |

| PUVA | -Excretion in breast milk, although no clear data on its effect on the infant-Experts recommend suspending or delaying breastfeeding for 5-24 h after the last dose (until 95% has been cleared in urine)-AEMPS: not mentioned | 13,104 |

| NBUVB | -No problems for infant-AEMPS: not mentioned | 56 |

| Apremilast | -Data in mice show that apremilast levels are 1.5-fold higher in milk than in blood-AEMPS: Given the paucity of available information at present, it is better to avoid apremilast during breastfeeding | 15,123 |

| Dimethyl fumarate | -Given the low molecular weight of this drug, levels in milk are likely to be approximately equivalent to those in maternal blood. Calculating the average level in maternal blood, the infant will receive roughly 3.5% of the dose adjusted for the mother’s weight-AEMPS: Contraindicated during breastfeeding | 108 |

| Methotrexate | -At immunomodulatory doses (<0.4 mg/kg/wk), levels in breast milk are very low (proportion of breast milk to plasma, 0.08:1)-AEMPS: Contraindicated during breastfeeding | 109 |

| Ciclosporin A | -Ciclosporin is excreted in breast milk, although levels were not detectable in most infants studied. Commercial presentations contain ethanol, which should also be taken into account during breastfeeding-AEMPS: Contraindicated during breastfeeding | 74,110 |

| Infliximab | - Not generally detected in breast milk or at low doses-AEMPS: As human immunoglobulins are excreted in milk, women should not breastfeed for at least 6 months after treatment | 124 |

| Adalimumab | -Not generally detected in breast milk or at low doses, with concentrations in human milk of 0.1% to 1.0% of the maternal serum level-AEMPS: Can be used during breastfeeding | 15,112 |

| Etanercept | -Not generally detected in breast milk or at low doses-AEMPS: Decide whether it is necessary to interrupt breastfeeding or interrupt treatment with etanercept after considering the benefit of breastfeeding for the child and the benefit of treatment for the mother. | 111 |

| Certolizumab pegol | -Not generally detected in breast milk or detected at low doses-Approved for use in breastfeeding by the EMA | 115 |

| Brodalumab | -Transfer to breast milk unknown-AEMPS: Decide whether to interrupt breastfeeding or to interrupt/not start treatment with brodalumab after considering the benefit of breastfeeding for the infant and the benefit of treatment for the mother | 15 |

| Secukinumab | -In general, not detected in breast milk or at low doses.-AEMPS: Decide whether breastfeeding is to be interrupted during treatment and for up to 20 wk after treatment or interrupt treatment, taking into account the benefit of breastfeeding for the child or the benefit of treatment for the mother | 15 |

| Ustekinumab | -No data in humans-AEMPS: The decision to interrupt breastfeeding during treatment and for up to 15 weeks after treatment or to suspend treatment should be taken after evaluating the beneficial effects of breastfeeding for the infant and the benefits of ustekinumab for the mother | 78,125 |

| Ixekizumab | -No data on humans-AEMPS: Decide whether it is necessary to interrupt breastfeeding or interrupt treatment with ixekizumab after considering the benefit of breastfeeding for the infant and the benefit of treatment for the mother | 15 |

| Guselkumab | -No data in humans-AEMPS: Decide whether to interrupt breastfeeding during treatment and up to 12 weeks after the last dose or suspend treatment, once the benefit of breastfeeding and the benefit of treatment for the mother have been considered | 126,127 |

Abbreviations: AEMPS, Agencia Española del Medicamento y Productos Sanitarios (Spanish Agency of Medicines and Medical Devices); EMA, European Medicine Agency; NBUVB, narrowband UV-B phototherapy.

The risk of a postpartum flare-up is important. In addition, mothers are more likely to experience Koebner phenomena owing to the irritation caused by suction and contact with the baby. Psoriasis in the area of the nipple generally manifests as well-defined erythematous plaques with fine scale.92

In principle, breastfeeding does not interfere with administration of most vaccines to the mother (both inactivated and attenuated), despite the presence of maternal antibodies in milk.93–95 An exception can be found in vaccines against smallpox and yellow fever. Since these vaccines have been associated with severe conditions in neonates, such as encephalitis, they are contraindicated.96,97

As during pregnancy, any decision taken during breastfeeding should be agreed upon with the patient.

Recommendation 16. Emollients can be prescribed during breastfeeding (LE 4; GR C, LA 83%).

There are no reports of emollients causing problems for neonates.

Recommendation 17. With respect to topical treatments for psoriasis during breastfeeding, tazarotene is contraindicated. Other topical agents can be used providing that the benefits outweigh the risks, at minimum doses, and for as short a period as possible. The area of the nipple and areola should be avoided (LE 4; GR C; LA 97%).

Despite the paucity of data, topical tazarotene is contraindicated. In general, no relevant problems have been reported for the other topical treatments, except for irritation of the baby’s skin and 1 case of iatrogenic hypertension in a baby whose mother was receiving a high-dose corticosteroid that included the area of the nipple.15,98–104

Recommendation 18. Topical PUVA is not recommended during breastfeeding. Narrowband UV-B phototherapy can be used (LE 4; GR C; LA 95%).

While there are no data on the effect on the infant,13,104 the experts recommend using another type of phototherapy. In this sense, narrowband UV-B phototherapy has proven safe during breastfeeding.56

Recommendation 19. Systemic corticosteroids can be used during breastfeeding as long as the benefits outweigh the risks. They should be administered at minimum doses and for as short a time as possible (LE 4; GR D; LA 80%).

Corticosteroids are excreted in low amounts in breast milk,105 and there have been no reports of adverse events in infants (although the studies analyzed show that the dose of corticosteroids taken by mothers was 5-10 mg/d).106

Recommendation 20. Oral retinoids, apremilast, dimethyl fumarate, methotrexate, and ciclosporin A are not recommended during breastfeeding (LE 4; GR D; LA 95%).

While oral retinoids are excreted in small amounts in breast milk, their possible cumulative toxicity remains unclear in newborns, whose immaturity may hamper their ability to eliminate these drugs.12,107

Apremilast is excreted in breast milk. While no studies have been performed in humans, the drug is contraindicated based on data from animal studies.56 Dimethyl fumarate is also excreted in breast milk, possibly at doses equivalent to the plasma doses of the mother; therefore, it is not recommended during breastfeeding.108

Methotrexate is excreted in very low concentrations in breast milk, and there are no data to suggest problems for neonates. However, since methotrexate has the capacity to accumulate in tissue, excretion could be hampered by renal immaturity in the neonate.109 Therefore, methotrexate is not recommended, as with ciclosporin A, which is also excreted, although levels in infants are almost undetectable.74,110

Recommendation 21. Certolizumab pegol has been approved for use during breastfeeding. For all other biologics, the panel recommends assessing the risks and benefits in each case (LE 4; GR D; LA 93%).

Since many monoclonal antibodies have a high molecular weight, they are excreted in breast milk in either very small amounts or not at all. Furthermore, most are digested in the newborn’s gastrointestinal tract.15,111–114 However, data on these agents are very scarce for newborns; therefore, prudence is recommended when prescribing.

Certolizumab pegol is excreted in breast milk either in very small amounts or not at all. No problems have been reported with neonates, and the drug is approved for use during breastfeeding.115

Recommendation 22. Once the pregnancy has come to term, usual follow-up should be resumed in the dermatology clinic as soon as possible (LE 5; GR D; LA 88%).

It is important to resume follow-up in the dermatology clinic as soon as possible after delivery, because there is a considerable risk of flare-ups at this time, mainly in patients whose disease was active during pregnancy, especially during the first trimester. Other factors associated with flare-ups include preterm delivery and low birth weight. The frequency of visits depends on the individual case.

Evaluation of the activity of psoriasis should be tailored in line with daily clinical practice.

Medications can be reintroduced or switched according to the patient’s progress. This means, for example, that a patient in remission whose medication was suspended because she was pregnant does not require the drug to be reintroduced while she continues to be in remission.

Recommendation 23. The neonate does not require special care, except if the mother has been exposed to biologics that cross the placenta and have been maintained beyond the second trimester (LE 5; GR D; SA 87%).

Neonates who have been exposed to drugs (monoclonal antibodies) that cross the placenta during pregnancy may have a slightly increased risk of infection over a variable period of up to 6-9 months.15 Therefore, in these cases, the newborn should be vaccinated with inactivated virus according to the vaccination schedule and with live virus only after 6 months. It is also recommended to perform laboratory testing during the first few weeks owing to the potential onset of neutropenia.

DiscussionIn the present document, which was promoted by the Psoriasis Working Group of the AEDV, we present a series of practical recommendations on fertility, pregnancy, postpartum, and breastfeeding for patients with psoriasis. The recommendations are based on the best currently available evidence.

We followed the nominal group method and the Delphi process, which are widely used for this type of document. Our approach was carried out with the participation of a nationally recognized multidisciplinary expert panel, who based the recommendations on a systematic review and their experience. We highlight the high level of agreement in the recommendations; only one did not reach the required level. In addition, the Delphi process was extended to a large group of dermatologists, thus reinforcing the validity of the recommendations.

The only recommendation for which the established level of agreement was not reached was that concerning referral to a gynecologist for reproductive counseling. This recommendation was rejected probably because the dermatologist felt responsible and able to counsel or at least inform the patient objectively and reliably about various aspects of reproduction. The present document will help in this task. After some reflection, it was decided not to reformulate the recommendation and, therefore, not to submit it for a second Delphi round.

The final objective of these recommendations is to improve outcomes in this area, but mainly in terms of pregnancy. In this sense, the expert panel would like to reinforce several messages. The first involves preconception counseling, which should be offered to all patients of reproductive age, irrespective of the treatment they receive. In addition, the professional’s door should always remain open so that the patient feels confident asking about any aspect of pregnancy: a well-informed patient is more likely to reach the objectives set. The panel also considers it essential to plan pregnancy correctly. Ideally, the woman should become pregnant when psoriasis is controlled (or as well controlled as possible) and patients are receiving drugs considered safe for the pregnancy and the fetus. Thus, this planning may involve, for example, a change in treatment or an in-depth evaluation of psoriasis. Finally, the outcome of pregnancy is more likely to be successful in a context of multidisciplinary care based on teamwork and identification and comprehension of the possible specific risks for an individual patient.

In summary, explicit recommendations must be made to guide clinicians in the management of patients with psoriasis during reproductive age. Although evidence remains scarce in some areas, this document presents a series of recommendations that we believe could prove relevant and useful. Furthermore, the recommendations are simple and can be implemented without difficulty. The panel is convinced that following the recommendations provided here will improve management of affected patients and, therefore, their prognosis and that of their descendants.

FundingThis project was funded by an unrestricted grant from UCB.

Conflicts of InterestMAM has given talks and provided consultancy services for and attended scientific meetings sponsored by AbbVie, Pfizer, MSD, Janssen, Novartis, Lilly, Almirall, Amgen, Cellgene, Leo, and UCB Pharma.

MGB has received clinical trial/study and speaking fees and grants for attending meetings and conferences from AbbVie, Novartis, LEO Pharma, Wyeth, MSD, Cellgene, Lilly, Janssen, and UCB Pharma.

OBR has received consultancy and speaking fees from Janssen-Cilag, AbbVie, Pfizer, Novartis, Lilly, Cellgene, Leo Pharma, UCB, and Almirall.

APF has received consultancy and speaking fees from AbbVie, Almirall, Leo, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, Cellgene, and Janssen.

JMC has received consultancy and speaking fees from Cellgene, Janssen, Lilly, Novartis, Leo Pharma, Pfizer, MSD, AbbVie, and Biogen Amgen.

RTF has received consultancy and speaking fees from Leo Pharma, Lilly, Janssen, Cellgene, Novartis, AbbVie, MSD, Pfizer, and Almirall.

IB has received consultancy and speaking fees from Cellgene, Janssen, Lilly, Novartis, Leo Pharma, Pfizer, MSD, AbbVie, and Amgen.

The remaining authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

We are grateful to the following doctors for their participation in the Delphi process: Gloria Aparicio Español, Ana Batalla Cebey, Marta Ferran Farrés, Alba Calleja Algarra, Antonio Sahuquillo Torralba, Servando Eugenio Marrón Moya, Carlos Ferrándiz Foraster, Daniel Jesús Godoy Díaz, Carlos Muñoz Santos, Álvaro González-Cantero, Noemí Eiris Salvado, Laura Salgado Boquete, Conrad Pujol Marco, Vicenç Rocamora Duran, Anna López Ferrer, Carmen Rodríguez Cerdeira, Elena del Alcázar Viladomiu, Rosario Fátima Lafuente Urrez, Ana María Carrizosa Esquivel, Amparo Pérez Ferriols, Ander Zulaica Garate, Diana P. Ruiz Genao, Almudena Mateu Puchades, Ignacio Yanguas Bayona, Almudena Fernández Orland, José Carlos Moreno Giménez, Alberto Romero Maté, Alberto Conde Taboada, Beatriz Pérez Suárez, Miquel Ribera Pibernat, Eva Vilarrasa Rull, José Manuel Fernández Armenteros, Silvia Pérez Barrio, Miren Josune Michelena Eceiza, Cristina Rubio Flores, José Carlos Ruiz Carrascosa, Mónica Larrea García, Gregorio Carretero Hernández, José Luis Sánchez Carazo, Marc Julià Manresa, Luis Puig Sanz, Lourdes Rodríguez Fernández-Freire, Manuel Galán Gutiérrez, Alicia González Quesada, Estrella Simal Gil, Juan José Andrés Lencina, María Luisa Alonso Pacheco, Laura García Fernández, Mar Llamas Velasco, Pablo de la Cueva Dobao, Jaime Notario Rosa, Fco. Javier García Latasa de Araníbar.

We thank Dr Estíbaliz Loza for her support and coordination of the methodology applied in the project.

Please cite this article as: Belinchón I, Velasco M, Ara-Martín M, Armesto Alonso S, Baniandrés Rodríguez O, Ferrándiz Pulido L et al. Consenso sobre las actuaciones a seguir durante la edad fértil, el embarazo, el posparto y la lactancia en pacientes con psoriasis. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2021;112:225–241.