A 27-year-old female presented with an asymptomatic nodule on the left thigh. She reported a smaller pigmented lesion since birth, with significant growth in the last 5 years. The patient had no personal or family history of skin cancer. She was otherwise healthy and had no systemic symptoms. She was doing oral contraception and no other medications.

Physical examination revealed a smooth nodular dome-shaped lesion measuring 1cm×2cm, with central hyperpigmented and peripheral erythematous areas, located on the medium third of the anterior left thigh (Fig. 1). There was no regional lymphadenopathy.

Dermoscopically there was a central dark hyperpigmented area surrounded by a rim of thin regular pigment network (Fig. 2). In the central area we observed a predominant globular pattern, an eccentric thickened pigment network and a blue-whitish-veil.

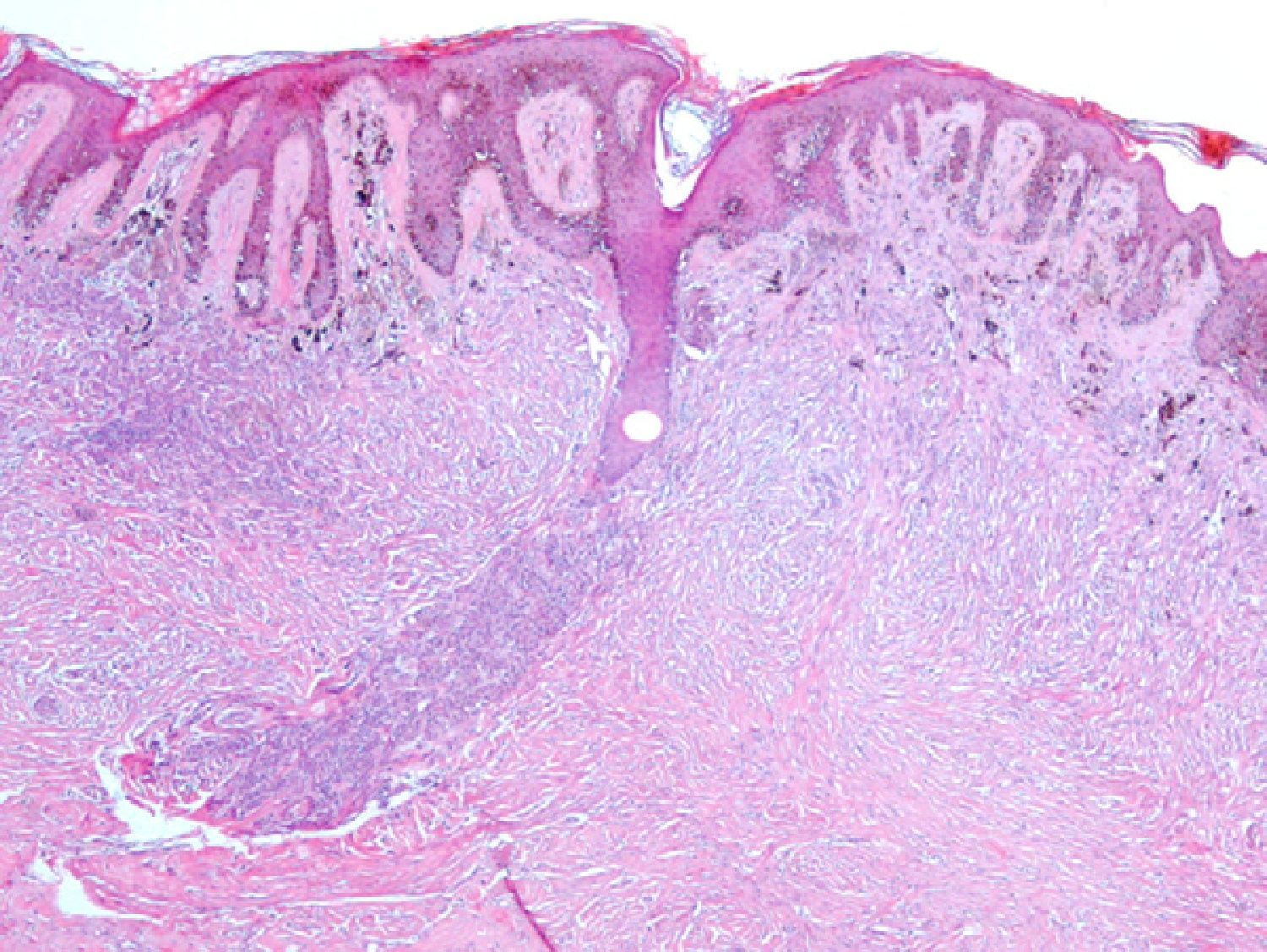

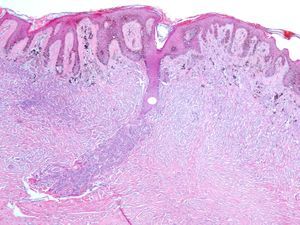

Excision was performed. Histological examination revealed a compound (predominantly intradermal) melanocytic nevus with congenital-like growth pattern and a dermatofibroma, with no signs of malignancy (Fig. 3). Nevus cells involved deep dermal appendages and neurovascular structures and they became progressively smaller in deeper portions of the lesion suggesting maturation and benignity. Intermingled with melanocytes, there was a proliferation of spindle fibro-histiocytic cells characteristic of dermatofibroma.

Collision tumors result from the combination of two or more benign and/or malignant neoplasms in a single lesion.1 As it is unknown whether the association is a random event or whether there is, in fact, a pathogenic relationship in the development of two distinctive neoplasms together, some authors propose the designation of compound tumor instead of collision tumor because the last one suggests the association is incidental.2

Collision tumors are not rare. Boyd and Rapini performed a retrospective evaluation of approximately 40,000 cutaneous biopsies, yielding 69 collision tumors.3 Cascajo and colleagues found 54 collision tumors of malignant cutaneous neoplasms associated with seborrheic keratoses in 85,000 biopsies.2

The most common combinations found by Boyd and Rapini included basal cell carcinoma and nevus (14), basal cell carcinoma and seborrheic keratosis (8), nevus and seborrheic keratosis (14), actinic keratosis and nevus (7), and basal cell carcinoma and neurofibroma (4).3 Another commonly described association is that of melanocytic nevus with desmoplastic trichoepithelioma.1 Our patient had a compound tumor of congenital nevus and dermatofibroma. As far as we know, this is the first reported case of such a combination.

Furthermore this tumor clinically and dermoscopically mimicked malignant melanoma. Although in some cases dermoscopy can help with collision tumor diagnosis,4 this was not the case. In fact, according to Giorgi and colleagues cutaneous collision tumors are extremely difficult to diagnose preoperatively, even with the help of dermoscopy, in particular when one of the lesions is melanocytic.5 The presence of a pigment network, the pathognomonic sign of the melanocytic lesion, allows dermatologists to use dermoscopic algorithms, which in this case ended up in the wrong preoperative diagnosis of a malignant lesion.

Please cite this article as: Osório F, et al. Large Asymmetric Pigmented Nodule in a 27-Year-Old Female. Actas Dermosifi- liogr. 2013; 104:165-6.