I have tried my best to rise as high as possible in everything my nature inclined me to, I have worked passionately, I have spared no effort in my work. Goethe

The spirit of Fermín Cubero del Castillo is well reflected in the phrases above from the celebrated German poet Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749–1832).† Dr Cubero's life was marked by his passionate devotion to his work and the great effort he made to realize his dream of becoming a doctor and dermatologist working at Hospital San Juan de Dios in Madrid. His goal may seem a very ordinary one from our position today, but meeting it required a labor of heroic proportions for him given the social order at the end of the 19th century and beginning of the 20th.

The turn of the century and the years leading to the 1930s were a golden age for Spanish dermatology, when the specialty surged forward toward a position of parity with practices in France and Germany, the leading countries at the time. In Spain, the hospital of reference in dermatology was Madrid's San Juan de Dios, where Dr José Eugenio de Olavide had taken charge of the facility's 120 beds in 1861, creating the country's first dermatology service. Major outcomes of Olavide's tenure there were the creation of a laboratory able to produce the micrographic images that were necessary to provide a solid scientific foundation for the specialty1; the publication of his Atlas of skin diseases between 1871 and 18802; and the creation and display of wax models to illustrate disease processes, a collection that would later form the basis of the Olavide Museum. These last 2 accomplishments were conceived for their instructional value above all.

The emergence of a Spanish school of dermatology was made possible by the invaluable cooperation and close association of figures of great prestige in this hospital setting. Among them were Eusebio Castelo Serra (1825–1892), who as director of Hospital de San Juan de Dios was Olavide's faithful ally; Manuel Sanz Bombín (1841–1918); and Eusebio Castelo's son Fernando (1855–1935). Also present was the person who would be the true founder of the Madrid school of dermatology and the professional association currently known as the Spanish Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (AEDV), namely Juan de Azúa (1858–1922). Alongside these prominent dermatologists were others of less renown whose names appeared often in documents and publications at this time and whose work was admirable: D. Pérez Gallego, J. Ametller, M. San Juan, P. Martínez, A. Colomo, M. Martin Romero, J. Olavide Malo, M. Serrano, F. López-Cerezo and, finally, Francisco Cubero, the subject of this article. Cubero's life was exemplary for his persistence and the sacrifices he made to achieve his dream of becoming a doctor and later a dermatologist working in Hospital San Juan de Dios.

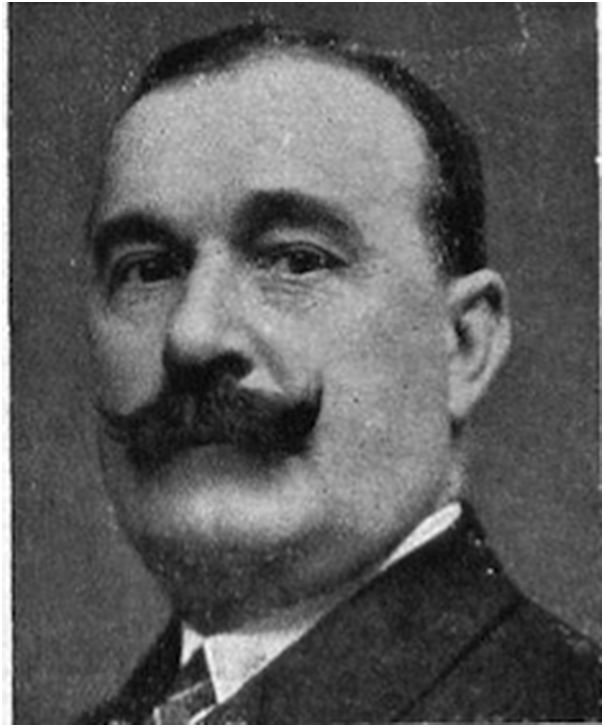

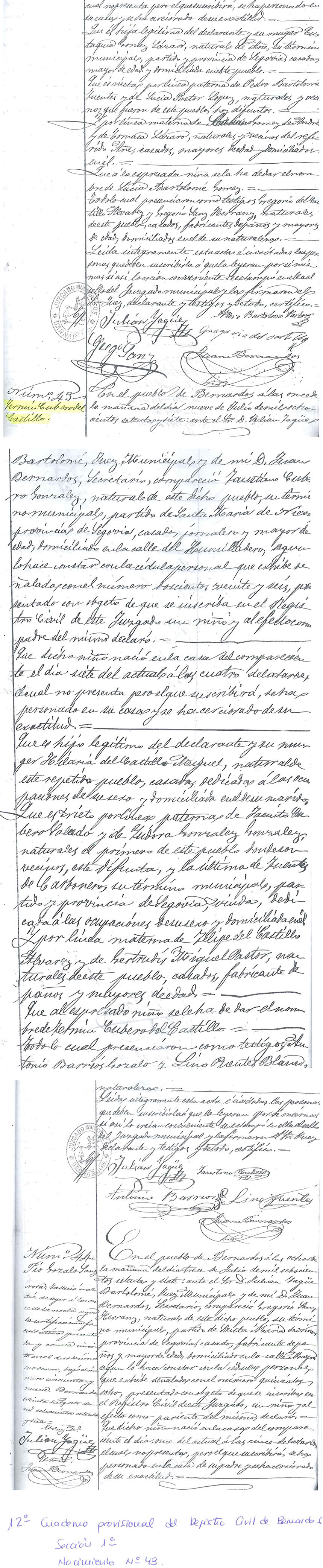

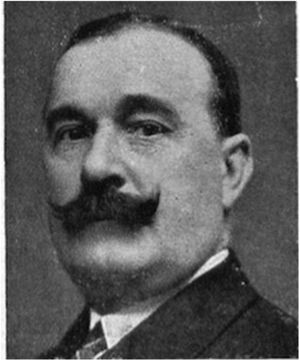

BiographyFermín Cubero del Castillo (1877–1943) (Fig. 1) was born on July 7, 1877, in Bernardos in the province of Segovia. His birth certificate (Fig. 2) lists Faustino Cubero González and Hilaria del Castillo Miguel as his parents. It is interesting to note that the town of Bernardos lies only 30km from Valseca de Boones, the birthplace of Pedro González Velasco (1815–1882), a doctor known to us as the founder of Madrid's Museum of Anthropology. The careers of these 2 men had much in common. The province of Segovia saw the birth of another of this period's great masters of Spanish dermatology: Eusebio Castelo, mentioned above.

Fermín Cubero del Castillo (1877–1943). Photograph reproduced from the entry for Dr Cubero in the book Cien años de la Medicina en Segovia, de J. M. Garrote Díaz.5

In spite of the comparatively prosperous time in which he was born, Fermín Cubero was not an especially fortunate child. He was born into an “extremely humble family, among the poorest in his town” according to an article about him titled “Tale of a woodcutter, a medical specialist, and a drummer boy” in the magazine El amigo.3 From an early age Cubero found himself obliged to work at various jobs to help support his family and could only rarely attend school. Thus, at times he was a dyer's apprentice or a woodcutter. At others he worked in a stone quarry or on road repairs or construction jobs around Bernardos. Figuras Segovianas — a publication of the cultural center of Segovia in Madrid (Centro Segoviano) — included an article on the occasion of a 1946 gathering to honor him 3 years after his death. The piece described Cubero's childhood in Bernardos, mentioning that scarcely had he reached the age of 12years when he began to ride a donkey into the forest to gather pine nuts to help his family. “That was how his life was tempered and his spirit strengthened, for poverty is the greatest way to forge souls as resilient as steel,” the writer added.

Always ready to try something new, Cubero took up playing the drum and cymbals after watching the performance of a puppet company at the age of 14years. He kept up this interest in music and in percussion in particular throughout his life, at first playing with a local band (the Terceto de Bernardos) that was hired to perform at town festivals. Much later, in 1935, he served as a judge in a historic competition in Segovia that featured music for the dulzaina and drum.

When he was about 20 years old, Cubero met the town doctor, Vicente del Río, who took kindly to the young man and began his education, training him to serve as his assistant. Their work together, around the time that Cubero developed a trichophytic infection refractory to treatment, would change the direction of his life.

Vicente del Río advised Cubero to go to Madrid for treatment at Hospital San Juan de Dio since the condition involved the skin. His young assistant therefore boarded a train in 1898 carrying a letter of presentation to Dr del Río's friend, one Dr Serrano. This referral seems to have been to Miguel Serrano, who would later take up the position of librarian-treasurer on the first board of directors‡ in 1909. Among the few things Cubero took with him to the city was a picture of Our Lady of the Castle of Bernardos. At the hospital's recently opened new facility on Calle de Esquerdo he was assigned bed 13 on the ground floor of pavilion 7.

A less plausible version of how Fermín Cubero first came to Hospital San Juan de Dios appeared in a 1927 article in the newspaper ABC under the headline “Labor Medal Awarded to Dr Cubero and Mr Pavón.”4 The report claimed that Fermín Cubero had been admitted at the age of 7years “suffering a serious skin disease that took long to cure.”

What is sure, in any case, is that meeting Dr Azúa in this hospital was a key event in Cubero's life. From the start, Azúa served as a mentor and greatly admired professional example.5 In 1932, 10 years after Azúa's death, Cubero and B. Fernández Gómez paid homage to their teacher with an account of his life§:

There is no doubt that Azúa ranked among the greatest Spanish physicians of his time. But above all, by his example he was an advocate of work and rose above ideologies and social or political systems. He was one of our most rigorous leaders in bridging the gap between speculation and cant in medicine on the one hand and serious experimentation on the other. Azúa was also among the most fervent Spanish proponents of collaboration among physicians and the conduct of original clinical research.5

At a time when the young Cubero could hardly read and write, Azúa hired him to clean the wards and little by little taught him the fundamentals of nursing and assisting at dermatologic surgery. After several years in which Cubero showed discipline, hard work and constancy, he was certified as a nurse (termed practicante). This achievement was the fruit of labors he had begun long before with Vicente del Río, the doctor he had met in Bernardos.

Now cured of his skin infection and satisfied with his situation in life, Fermín Cubero returned to his home town, opened a barber shop and began to assist his first mentor again. He soon outgrew Bernardos, however, and returned to Madrid to learn more. There he again sought out Drs Azúa and Serrano. While living modestly in quarters with a small office in Calle del Mesón de Paredes, Cubero provided nursing care for patients sent to him by Dr Azua. Soon after, he competed for and won a permanent staff position as nurse under one Dr Ustariz of Hospital de la Princesa in Madrid.

According to an entry in the online resource provided by the Universidad Complutense de Madrid on the lives of eminent physicians,6 Cubero contracted typhoid fever while working with patients during the city's 1909 epidemic. The same source reports that he opened a clinic to treat syphilitic and other dermatologic diseases at number 18 Plaza de Salmerón (now Plaza de Cascorro) in the heart of Madrid's Rastro district. He also continued to treat many patients sent by Dr Azúa at this time. At the age of 26years, Cubero prepared to be admitted to the Instituto Cardenal Cisneros, a secondary school where he earned his degree in 3years. He then took a preparatory course to enter the medical school of Madrid's Universidad Central as an external student. By the time he completed his studies and received his degree in 1915 at the age of 38years, Cubero had the status of official student.6 He at once proudly hung the diploma in his office in Plaza de Salmerón, where the words “Cubero del Castillo–Physician” could be read in large letters. His dream had been fulfilled over the course of many years working with Dr Azúa in Hospital San Juan de Dios.

Cubero was named an assisting physician (médico auxiliar) at the hospital in 1926 and on December 10, 1927, the Minister of Labor, Eduardo Aunós, awarded him the ministry's medal in a ceremony at the hospital. Dr José Sánchez-Covisa spoke.4 This same year, Cubero was proclaimed an honored son of his native town, Bernardos.

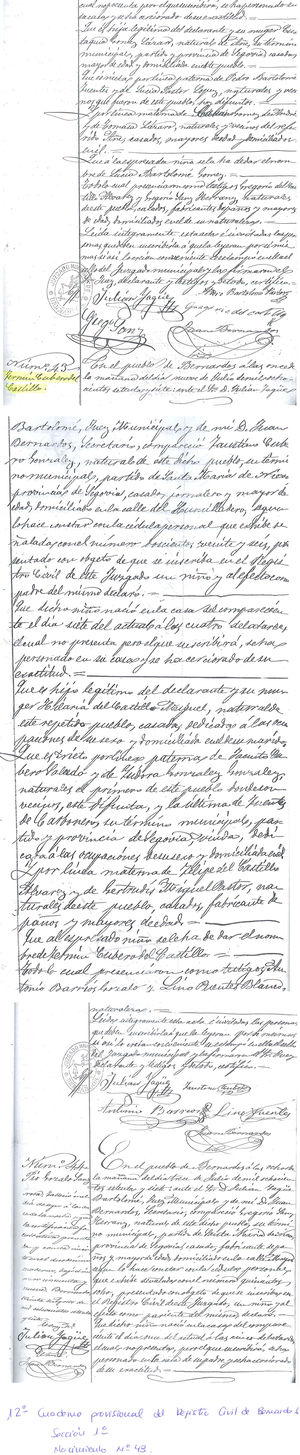

In 1928 Cubero became a full member (numerario) of the association that would become the Spanish Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (AEDV). That year another celebration in his honor was held in Bernardos, this time in the chapel dedicated to the town's patron, Our Lady of the Castle. According to the local inhabitants, a drum printed with Cubero's photograph was on display there. Although the drum has been lost, a photograph confirms the account (Fig. 3).

Fermín Cubero's drum, dedicated to Our Lady of the Castle of Bernardos. This drum is mentioned in many articles about Cubero but it seems to have been lost during refurbishment work in the chapel dedicated to the Virgen. The following words appear around the perimeter: “I offer this drum, which I used for many years, to my patron, Our Lady of the Castle, in gratitude for the many blessings I have received through her intercession. Madrid. Dr Fermín Cubero.” The photograph was provided by José U. Bernardos Sanz.

In 1939 the Provincial Council (Diputación) of Madrid awarded him a permanent position as physician and professor of medicine. He served as president of the Segovian cultural center in Madrid from 1935 to 1943, where an event honoring him was celebrated in 1943.

Cubero married Alejandra Herrero Crespo, who gave birth to their 2 daughters, María Antonia and María Concepción Cubero Herrero. The family resided at number 13,Calle de los Relatores, near Cubero's medical dispensary. On his death in 1943, the provincial administration for charity recognized Cubero's important contributions by allocating a pension for the support of his daughters.

Research and PublicationsFermín Cubero published in the journal Ecos Españoles de Dermatología y Sifilografía (Spanish Reflections on Dermatology and Syphilology). Two of his articles appeared in a 1933 special issue celebrating dermatology. One article, coauthored with Fernández Gómez, sketched the history of their specialty in Spain,7 and the other described a case of actinomycosis.8

Cubero and Fernández Gómez then published a series of 5 articles in 1934 in the same journal, describing the life and career of the Spanish dermatologist Juan de Azúa y Suarez.9–13 This account, written by 2 of Azúa's own disciples, provides the most complete and plausible account we have, covering Azúa's entire life, from birth to death, and his work. The first article includes a preamble under the title “A Few Preliminary Words” (“Dos palabras previas”).9 In it the coauthors described their reason for writing the biography at that time, 10 years after the subject's death, saying “if this account is not recorded now, we run the risk that those who knew [Dr Azúa] will begin to disappear and only an indistinct figure pieced together from scraps of information and second-hand references will remain.”

Actas Dermo-Sifiliográficas also published 16 articles by Cubero between 1919 and 1929. Most concerned venereal diseases. Curiously, 2 separate periods can be discerned. The first saw the publication of 7 articles in 1919 and 1920; the second saw another 9 articles in 1927 and 1929.

A third journal, Cultura Integral y Femenina (Holistic and Women's Culture) published a curious article by Cubero about the important functions of human skin and the danger of certain beliefs and habits related to skin care. He discussed homemade remedies critically and in a section about cosmetics described the problems of some hair dyes, rouges and even the painted beauty marks that were so popular at the time. Around the same time, Cubero and M. Sánchez Taboada offered short courses of 25 sessions on topics in dermatology and syphilology that were open to small groups of 15 students.

A fan of both bullfighting and the opera, Cubero was acquainted with famous bullfighters (Juan Belmonte and Marcial Lalanda) and singers (such as the tenor Titta Rufo). At the café El Cocodrilo in Plaza de Santa Ana, which was frequented by well-known personalities of the day (the Count of Adanero and the Marquess of Arcos among others), Cubero met daily with friends who shared his interests. When Fermín Cubero del Castillo died on July 11, 1943, he was buried in Madrid's Cemetery of Our Lady of Almudena (section 44N, block 12, letter A).

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Our thanks to Cristina Villacorta Benito, administrative assistant to the town council of Bernardos, for her help in locating the birth certificate of Fermín Cubero del Castillo. We also thank José U. Bernardos Sanz, professor in the Department of Applied Economics and the History of Economics, at the Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia (UNED), Madrid.

The phrases attributed to Goethe have been translated directly from Spanish because no verifiable source for this quote could be found in English translations of Goethe's work or in German collections. (M. E. Kerans, translator)

Please cite this article as: Conde-Salazar Gómez L, Maruri A, Aranda D. Fermín Cubero del Castillo. Historia de un esfuerzo y tenacidad encomiables. Actas Dermo-Sifiliográficas. 2019;110:814–818.

Mention of the “first board of directors” refers not to the hospital's but to that of the association that would become the present-day AEDV. The roles of librarian (“historian”) and treasurer were combined on the early boards, and Dr Serrano was the first to hold the position, according to Conde-Salazar (2018). (See Conde-Salazar L, Aranda D, Maruri A. The library of the Spanish Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (AEDV). 2018;109(8):708-11. PMID: 29861039.) (Translator)

The blocked quotation that follows, about Dr. Azúa, is described in this paragraph as being written by Cubero and Fernández Gómez. However, it carries a citation to reference 5 in the original Spanish article and this English translatore. Reference 5, by Garrote Díaz, is a secondary source in which ellipses were placed between the first and second sentences that appear in the blocked quotation. The primary source for these words, however, is mainly reference 13, by Cubero and Fernandez Gómez: the first sentence comes from p. 45 of reference 13, the second from a portion of a paragraph on p. 46, and the last once again from p. 45. The third, however, could not be located in reference 13. It may be Garrote Díaz's synthesis of Azúa's life as presented in references 9 through 13. Alternatively, Garrote Díaz may have quoted from an earlier manuscript version of the primary reference 13, which was published in 1934, 2 years later than reference 5. (Translator)

- Home

- All contents

- Publish your article

- About the journal

- Metrics