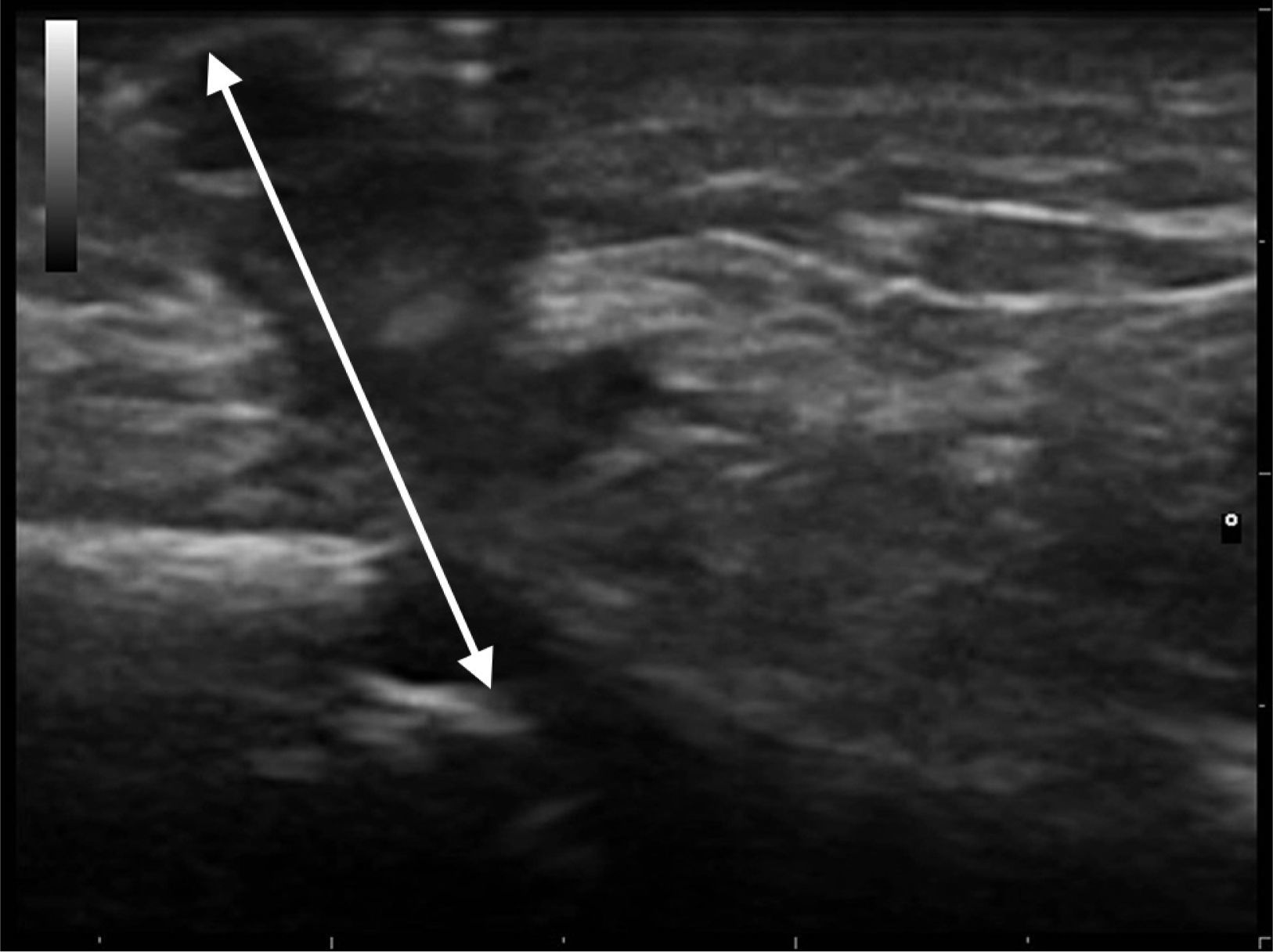

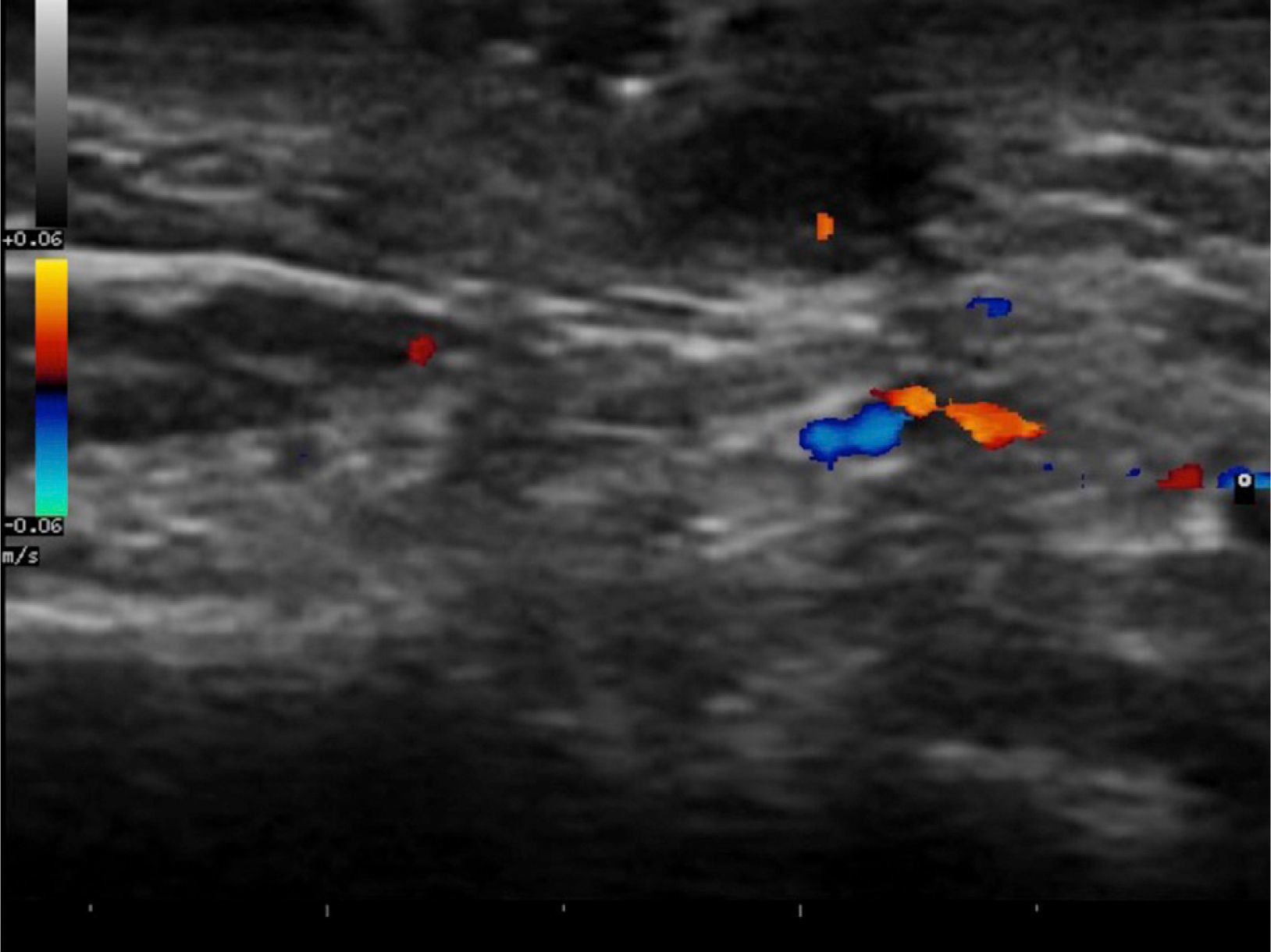

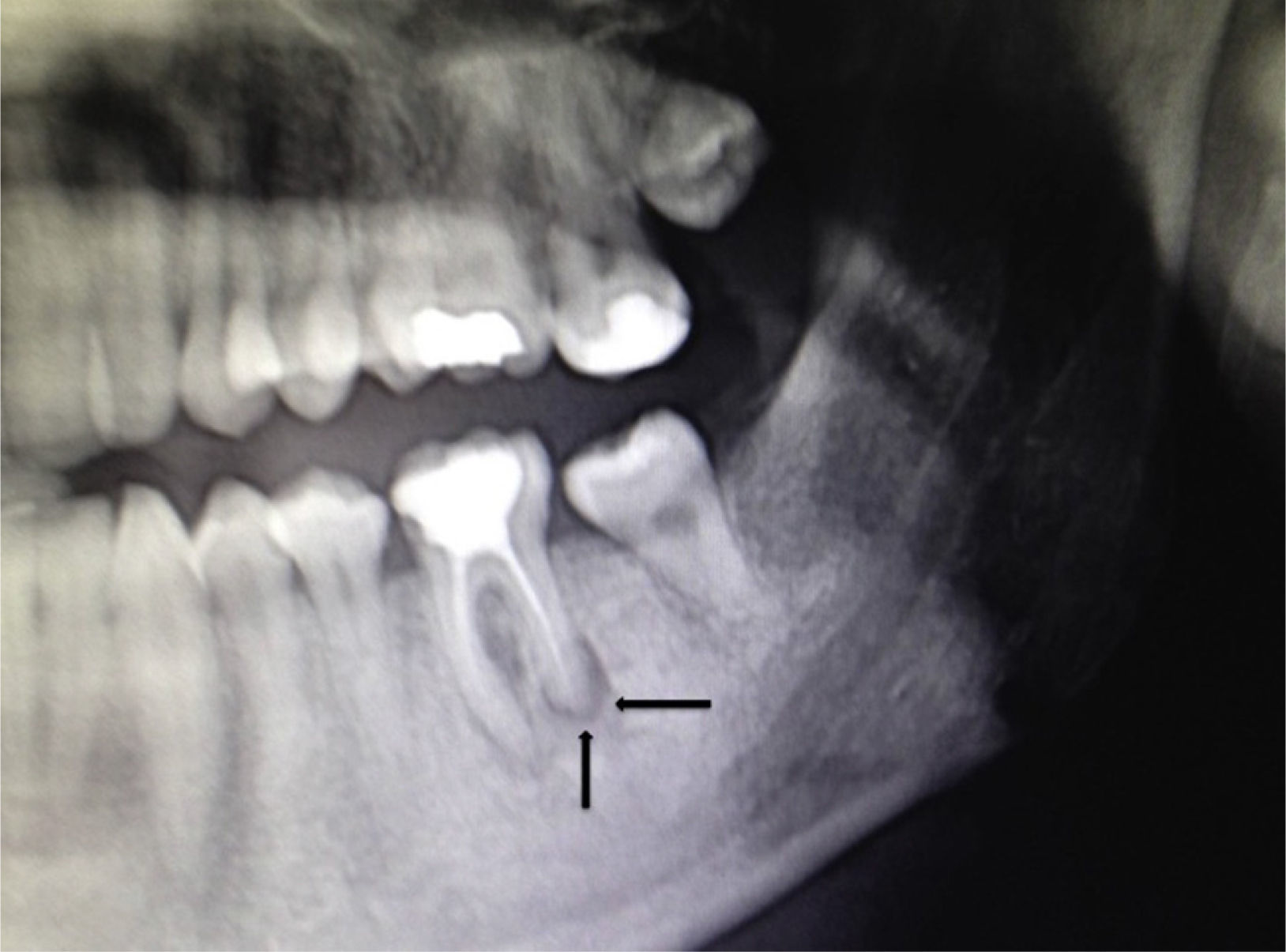

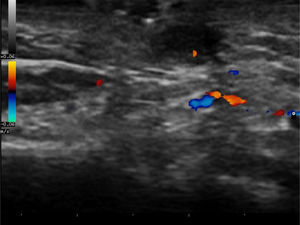

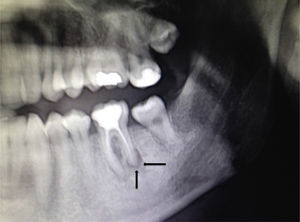

The patient was a 32-year-old man with no past history of interest. He was seen in dermatology outpatients for a tumor in the form of a cutaneous horn sunken into the skin over the left horizontal ramus of the mandible (Fig. 1). Examination revealed no alterations of the oral cavity. The patient stated that the region was tender. He had applied topical treatment with 2% mupirocin ointment without improvement. B mode skin ultrasound (Esaote, Genoa, Italy) using an 18MHz probe revealed a slightly tortuous, relatively well-defined, hypoechoic linear structure that extended to the surface of the cortical bone of the mandible (Fig. 2). Doppler study showed blood vessels in the area around the tract, suggestive of inflammation, and a poorly defined hypoechoic outline in B mode (Fig. 3). With a diagnosis of cutaneous odontogenic sinus, the patient was referred to the maxillofacial surgery department, where the study was completed with orthopantomography. This x-ray study revealed a radiolucent image that surrounded the apex of the posterior root of the left first molar (Fig. 4). Conservative treatment was performed with endodontia and restoration with an amalgam filling, leading to resolution of the cutaneous sinus in 20 days.

Cutaneous odontogenic sinuses are usually the result of pulp necrosis and chronic apical periodontitis. Patients do not typically relate these facial lesions with dental disease as associated pain is uncommon.1 The lesions are often diagnosed as skin lesions, leading to the erroneous prescription of unnecessary treatments that do not resolve the problem but do delay endodontic treatment that will eliminate the dental infection and lead to closure and healing of the extraoral sinus. The diagnosis is usually made by inspection, palpation, and orthopantomography. Depending on the site of the abscess, the sinus may be intraoral or the tract may run to the skin, following the path of least resistence2 dictated in part by muscle attachments.3 These sinuses are more commonly associated with mandibular teeth (80%) than with maxillary teeth (20%).4 They can also open into the nasal region, nasolabial folds, or at the medial canthus of the eye.5,6 The cutaneous opening of the sinus has an erythematous appearance and is ulcerated in the acute phase. The perilesional skin is usually slightly depressed.5–7 It is sometimes possible to palpate a fibrous cord that unites the site on the skin where the sinus opens with the incisor or molar that has caused the condition. Purulent material may be expressed through the cutaneous orifice when pressure is applied to the fibrous cord.5,6

The differential diagnosis includes odontogenic cysts, foreign body reaction, salivary gland fistulas, pyogenic granuloma, tumors, and infectious diseases. Bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw should also be considered, particularly if there are multiple sinuses.8

No effective treatment has been established, although conservative management would appear to be the best approach. Aggressive debridement should be avoided due to the risk of subsequent recurrence and sequelae.9,10

Recently, Shobatake et al.5 published 3 cases of cutaneous odontogenic sinuses diagnosed by ultrasound. Dermatologic ultrasound shows a well-recognized pattern with a relatively well-defined, linear but slightly tortuous, hypoechoic sinus tract that is seen to reach the surface of the cortical bone; Doppler reveals a variable degree of vascularization. Ultrasound is a tool that complements other radiologic techniques and requires little time to perform. It is an excellent option to facilitate the diagnosis of this type of lesion, even for dermatologists with little experience in the management of oral pathology. In addition, it can be used to monitor therapy and to evaluate the associated inflammation to help determine a possible indication for antibiotic prophylaxis prior to intervention.

Please cite this article as: Garrido Colmenero C, Blasco Morente G, Latorre Fuentes JM, Ruiz Villaverde R. Utilidad de la ecografía doppler color para el diagnóstico de fístulas dentocutáneas. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2015;106:678–680.