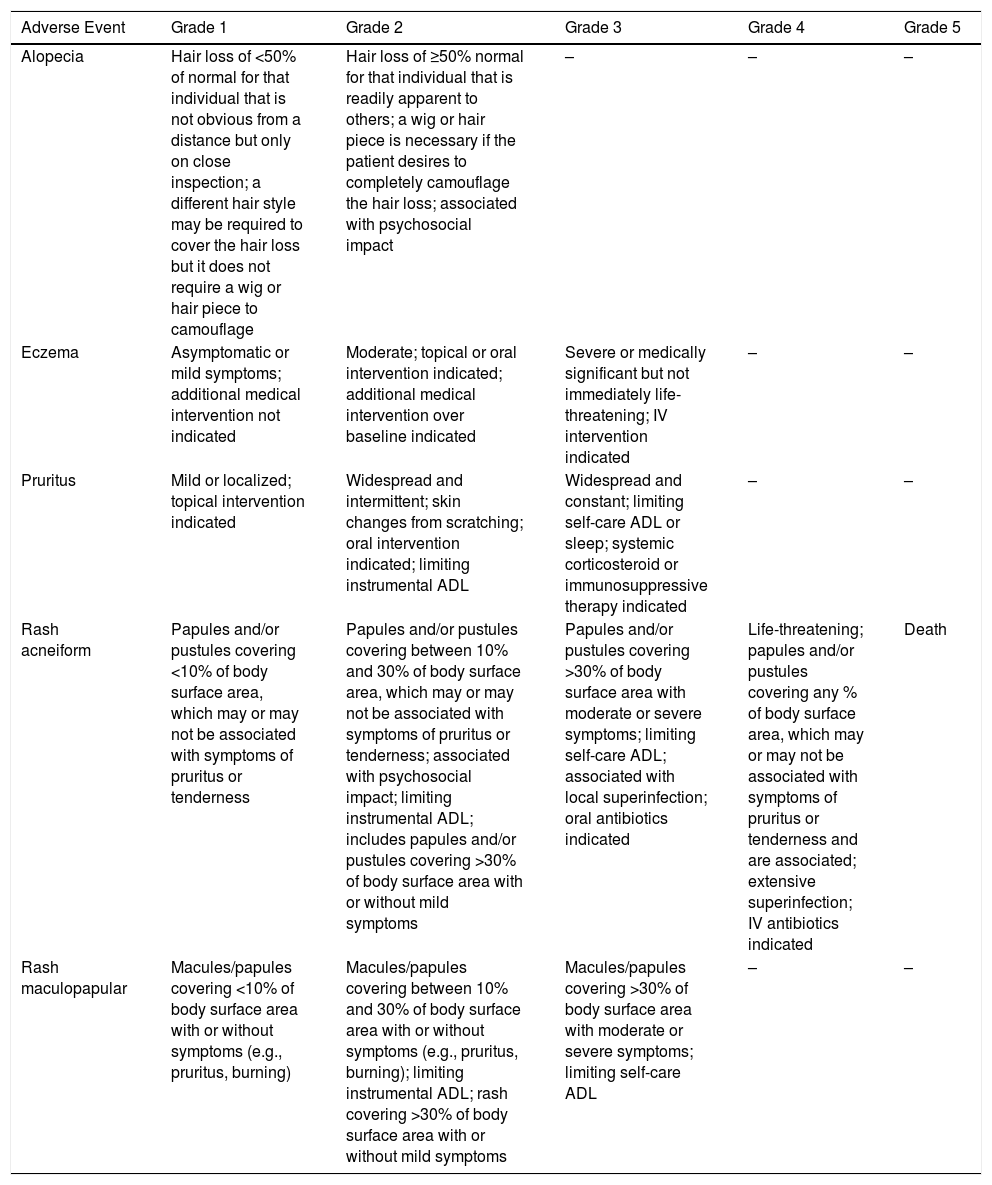

Cancer is one of the main causes of morbidity and mortality in developed countries, and survival has increased due to the advent of new therapies and their combinations.1 Adverse events (AE) from antitumor therapies, however, are multiple. The skin, and its adnexa, is one of the main organs affected, with abnormalities in up to 25% of patients who receive immunotherapy,2 and up to 100% of patients who receive classical cytotoxic chemotherapy.3 Today, both during clinical trials of oncologic drugs and in routine oncologic practice, AEs are graded using version 5.0 of the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE v5.0),4 published in November 2017 by the United States National Cancer Institute. This document aims to provide a standardized description of the terms that allow for an optimal exchange of information on the safety of antitumor therapies and the appropriate treatment of their AEs. The CTCAE v5.0 includes a number of signs, symptoms and abnormal test results attributed to antitumor therapies, and includes a total of 47 dermatologic AEs.4 The CTCAE v5.0 grades the AEs based on their severity on a 5-point scale, which goes from Grade 1 (mild, asymptomatic or with few associated symptoms, clinical observation, no intervention required, preventive treatment if available) to Grade 5 (death, which is not observed in most dermatologic AEs). (Table 1). Dermatologic AEs, such as pruritus, alopecia, rash, and vasculitis, are included because of their frequency and, indeed, their impact on the quality of life of the affected patients.5

Most Frequent Adverse Events Included in the CTCAE v5.0.

| Adverse Event | Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 3 | Grade 4 | Grade 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alopecia | Hair loss of <50% of normal for that individual that is not obvious from a distance but only on close inspection; a different hair style may be required to cover the hair loss but it does not require a wig or hair piece to camouflage | Hair loss of ≥50% normal for that individual that is readily apparent to others; a wig or hair piece is necessary if the patient desires to completely camouflage the hair loss; associated with psychosocial impact | – | – | – |

| Eczema | Asymptomatic or mild symptoms; additional medical intervention not indicated | Moderate; topical or oral intervention indicated; additional medical intervention over baseline indicated | Severe or medically significant but not immediately life-threatening; IV intervention indicated | – | – |

| Pruritus | Mild or localized; topical intervention indicated | Widespread and intermittent; skin changes from scratching; oral intervention indicated; limiting instrumental ADL | Widespread and constant; limiting self-care ADL or sleep; systemic corticosteroid or immunosuppressive therapy indicated | – | – |

| Rash acneiform | Papules and/or pustules covering <10% of body surface area, which may or may not be associated with symptoms of pruritus or tenderness | Papules and/or pustules covering between 10% and 30% of body surface area, which may or may not be associated with symptoms of pruritus or tenderness; associated with psychosocial impact; limiting instrumental ADL; includes papules and/or pustules covering >30% of body surface area with or without mild symptoms | Papules and/or pustules covering >30% of body surface area with moderate or severe symptoms; limiting self-care ADL; associated with local superinfection; oral antibiotics indicated | Life-threatening; papules and/or pustules covering any % of body surface area, which may or may not be associated with symptoms of pruritus or tenderness and are associated; extensive superinfection; IV antibiotics indicated | Death |

| Rash maculopapular | Macules/papules covering <10% of body surface area with or without symptoms (e.g., pruritus, burning) | Macules/papules covering between 10% and 30% of body surface area with or without symptoms (e.g., pruritus, burning); limiting instrumental ADL; rash covering >30% of body surface area with or without mild symptoms | Macules/papules covering >30% of body surface area with moderate or severe symptoms; limiting self-care ADL | – | – |

Activities of daily living (ADL): instrumental ADL refer to preparing meals, shopping for groceries or clothes, using the telephone, managing money, etc.; Self-care ADL refer to bathing, dressing and undressing, feeding self, using the toilet, taking medications. Grade 1 (mild): asymptomatic or mild symptoms; clinical observation only; treatment not indicated. Grade 2 (moderate): minimal, local or noninvasive intervention indicated; limiting age-appropriate instrumental ADL. Grade 3 (severe): severe or medically significant but not immediately life-threatening; hospitalization or prolongation of hospitalization indicated; disabling; limiting self-care ADL Grade 4 (life-threatening consequences): urgent intervention indicated. Level 5 (death) related to the adverse event.

Other dermatologic diagnoses are included on the official CTCAE v5 website https://ctep.cancer.gov/protocoldevelopment/electronic_applications/docs/ctcae_v5_quick_reference_5x7.pdf.

The CTCAE has been used in studies recently published in the dermatologic literature to evaluate the severity of cutaneous AEs from antitumor therapies. For example, one of the AEs with the greatest impact on skin is alopecia; both persistent postchemotherapy alopecia and alopecia associated with endocrine therapies in patients with breast cancer, where even with a grade-1 alopecia on the CTCAE v5.0 (less than 50% hair loss, obvious to the patient and doctor but does not require a wig or hairpiece to camouflage), patients suffer from a major emotional impact (42/100 on the Hairdex questionnaire).6 This simplified classification in 2 grades for alopecia is, however, nonspecific and does not help in assessing mild clinical improvement in patient follow-up, unlike other scores used in dermatology, which do permit this assessment, such as for male pattern baldness.7 Unlike alopecia, the CTCAE v5.0 allows for a good assessment of the severity of pruritus and facilitates its clinical treatment.

Guidelines exist with therapeutic recommendations for AEs from antitumor therapies based on their severity.8,9 For example, if we diagnose grade-3 pruritus on the CTCAE v5.0 in a patient with metastatic melanoma who is undergoing immunotherapy, this will indicate to the oncologist that the pruritus is generalized and constant during the day, that it limits daily activities and even sleep, and suggests the use of systemic corticosteroids or other immunosuppressant therapies. Furthermore, the shared use of this terminology among dermatologists and oncologists would make it possible to create an appropriate database to facilitate future scientific or pharmacovigilance studies.

Rash or exanthema is one of the most frequent AEs in oncology (up to 50% of patients with ipilimumab, used in metastatic melanoma).2 Most published clinical trials of antitumor drugs do not discern between the different clinical-pathologic subtypes (maculopapular, acneiform, lichenoid, psoriasiform),2 and a biopsy is probably required to determine the etiology, at the appropriate moment in the course of the rash. For oncologists, however, this procedure is limited and it is where dermatologists should act to define and guide the diagnosis of that rash and its most appropriate treatment. This suggests the need to include dermatologists in the evaluation of AEs from antitumor drugs in order to also facilitate treatment of the AE and thus improve the quality of life of oncologic patients.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Freites-Martinez A, Santana N, Arias-Santiago S, Viera A. CTCAE versión 5.0. Evaluación de la gravedad de los eventos adversos dermatológicos de las terapias antineoplásicas. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2021;112:90–92.