Syphilis is a sexually transmitted infection (STI) caused by the spirochete Treponema pallidum pallidum. Recent years have seen a resurgence of syphilis. This is mainly due to an increased number of cases diagnosed in men who have sex with men (MSM).1 Infection is associated with erratic condom use and a high number of sexual partners in the months before diagnosis.2

In Spain the incidence of syphilis has tripled since the beginning of this century, increasing from 1.96 to 5.70 per 100 000 population between 1998 and 2008..1,3

Even with effective treatment, the disease remains a significant public health problem with high associated economic costs.2,3 Correct diagnosis is crucial in order to start antibiotic therapy as soon as possible and thus prevent new infections and stop the progression of the disease and associated sequelae.4 Accordingly, new, more effective diagnostic techniques are required.

Traditionally the diagnosis of syphilis is based on a combination of clinical signs and symptoms, serological tests, and direct detection of the organism using dark field microscopy and silver impregnation techniques.1,5,6 A definitive diagnosis can be reached only by direct detection of the microorganism in infected tissues.7

These diagnostic methods can yield conflicting results in many clinical situations. Obtaining the clinical history of a patient with an STI can be difficult due to feelings of embarrassment or guilt.4 Moreover, syphilis has a wide range of clinical manifestations, which has earned it the epigram the great imitator. It can present with very atypical clinical features and hence be mistaken for genital ulcers or other different types of rash.4–6,8 Clinical diagnosis thus depends on the experience of the physician and the presence of lesions.5

Serology, using a combination of nontreponemal tests (Venereal Disease Research Laboratory and rapid plasma reagin) and treponemal tests (fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption and Treponema pallidum particle agglutination assay), has become the most commonly used means of indirect diagnosis, with proven benefits for the diagnosis and monitoring of patients after the initiation of treatment, although several acute and chronic infections can produce false positives in nontreponemal tests While treponemal tests are highly specific and sensitive (almost 100%) in cases of secondary syphilis, sensitivity and/or specificity are lower in the early stages of infection, in cases of congenital and tertiary syphilis, neurosyphilis with HIV coinfection, and in other immunosuppressive conditions.1,5,6,9 The increasingly common association of syphilis with HIV should be noted, given the confusion that can arise due to serological test results in these cases and the quite atypical clinical course.5

For direct detection of T pallidum dark field microscopy is sensitive but not specific, and requires trained personnel. Silver impregnation techniques are of low sensitivity (33% to 71%) and low specificity. Moreover, they give rise to numerous field artifacts and lack the necessary specificity to identify contaminant nontreponemal spirochetes (e.g., in oral mucosa).5,6,9

Several recently published findings support the role of biopsy with immunohistochemistry (IHC) using antitreponemal antibodies for the diagnosis of syphilis. One study comparing IHC with silver impregnation techniques concluded that the former was more sensitive.8 Indeed, the sensitivity of IHC is over 90% in most cases, although lower values (71%) have been reported in some studies.10 Sensitivity and specificity are highest in early primary and secondary syphilis (when spirochetes are found in large quantities), but diminish in later stages due to decreases in the number of microorganisms in the lesions.5 IHC can distinguish syphilis lesions from other unrelated lesions, which may appear in patients with both true and false positive serology for T pallidum. Moreover, this technique permits the detection of spirochetes in the skin, although cross-reactivity with Borrelia species is possible.4 Furthermore, IHC is a relatively rapid and inexpensive technique, with results available in about 48h.

Here we present 5 clinical cases of patients treated in our STI outpatient clinic between January 2009 and January 2012 with a final diagnosis of syphilis (Table 1); in all cases IHC was crucial for accurate diagnosis. The selected cases are representative of those seen in everyday practice, in terms of their clinical manifestations and/or doubtful or even negative serology, and thus were difficult to diagnose. Case 1 was an HIV-positive patient with a negative treponemal test, a lesion suggestive of syphilitic chancre, and no lymph node enlargement. This test result may have been due to the window period, or may reflect a false negative influenced by HIV co-infection. In case 2, the patient had a lesion suggestive of syphilitic chancre, but a negative enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), which was also probably due to the window period. Similarly, the negative ELISA in case 3, despite lesions suggestive of secondary syphilis, was probably a rare case of a false negative using this technique. The patient in case 4 presented rarely seen clinical features with a faint macular rash without palmoplantar involvement. Finally, case 5 (Figs. 1 and 2) is an example of atypical extragenital clinical manifestations.

Clinical and Serological Features of the 5 Clinical Cases.

| Clinical Cases | Sex | Age | Clinical Features | HIV | ELISA | RPR | TPHA | Case Details | IHC |

| Case 1 | M | 42 | Painful genital ulcer Swollen lymph nodes | + | + | 1/4 | − | TPHA | + |

| Case 2 | M | 54 | Two painful genital ulcers Swollen lymph nodes | − | − | NP | NP | ELISA with typical clinical features | + |

| Case 3 | M | 37 | Plaques with depressed center and multiple non-painful ulcers in the pubic area | − | − | NP | NP | ELISA with typical clinical features | + |

| Case 4 | M | 47 | Faint macular rash without palmoplantar involvement | − | + | 1/64 | 1/2560 | Atypical clinical features | + |

| Case 5 | F | 55 | Whitish papillary lesions on the lateral border of the tongue | − | NP | 1/128 | 1/2560 | Atypical clinical features | + |

Abbreviations: ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; F, female; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; IHC, immunohistochemistry; M, male; NP, not performed; RPR, rapid plasma regain; TPHA, Treponema pallidum haemagglutination test.

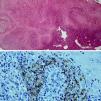

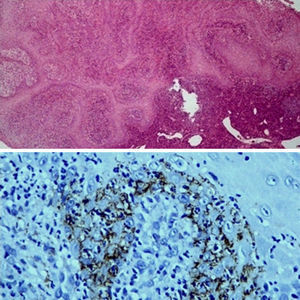

Biopsy of the lesion shown in Figure 1. Upper image: intense inflammatory infiltrate with a predominance of plasma cells (hematoxylin-eosin, original magnification × 50). Lower panel: IHC of the same biopsy (original magnification × 400) showing infiltration of treponemata, which appear as brownish bead-like structures.

IHC offers increased sensitivity and specificity compared with conventional techniques for the detection of T pallidum.3–6,8–10 Although this technique is not a widely used diagnostic method and we do not recommend its routine use, these 5 cases highlight its utility, especially in HIV patients or immunosuppressed patients in general, in those with secondary syphilis with negative and/or dubious serology, in cases with atypical clinical features (including cases of extragenital syphilis), and in the early stages of the disease.

Please cite this article as: Hernández C, Fúnez R, Repiso B, Frieyro M. Utilidad de la inmunohistoquímica con anticuerpos antitreponema en el diagnóstico de la sífilis. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2013;104:926–928.